For a woman as famous as Cleopatra, it is remarkably difficult to find good information. All of my sources contradicted each other, even on major points. The first biography I read went on and on about how Cleopatra would have done this and would have done that, and I was wondering what’s with all the third conditional tense? Let’s hear what she actually did do!

Why the confusion? Well, the most readily available sources are Roman. Those authors were often far from the action, usually long afterwards, and utterly united in their hatred of Cleopatra. As a result, the history tends to read less like a biography of her, and more like Sordid Scenes from the Lives of Various Roman Men. Unfortunately, they are the best we’ve got. The Egyptian sources are mostly destroyed or under water. Arabic sources were written even later than the Roman ones. So historians are forced into the business of making judgment calls about what’s true and what’s slander. We just do the best we can.

Cleopatra was born into the Ptolemaic dynasty, which is traditionally snubbed by Egyptologists because the Ptolemies came to power after Alexander the Great invaded, making them more Greek than Egyptian. This is silly. Egypt had existed for 3000 years, and the Ptolemies were not the first invaders. Those dynasties still count as Egyptian.

By the time Cleopatra was born in about 70 B.C.E., her family had ruled Egypt for 300 years. They both supported and participated in Egyptian religious rituals. They were portrayed in art as traditional Egyptian pharaohs. Cleopatra conversed with her subjects in their native tongue, who accepted her as an Egyptian pharaoh.

The Ptolemies had picked up Egypt’s favorite method of consolidating power by blatantly ignoring traditional family values like genetic diversity. Most of the Ptolemaic pharaohs married their sisters. Even their names are homogeneous. Almost all of the boys are named Ptolemy, and many of the girls are named Cleopatra. It makes a terrible mess out of any attempt to understand what’s going on. Our Cleopatra, by which I mean THE Cleopatra, was actually Cleopatra VII.

Her father was Ptolemy XII, but historians generally use his nickname, Auletes[1] , in a desperate attempt to keep things straight. Auletes ruled Egypt in a time when the Romans were flexing their muscles. Egypt was famously wealthy, a tempting target. It was a delicate situation.

Auletes definitely married Cleopatra V, who may have been his sister. She definitely had one daughter. Then she falls out of the record and Auletes acknowledges several more children, including two girls, both named Cleopatra. Were they all born to Cleopatra V? Maybe. Or did she die? If so, who replaced her? Maybe a native Egyptian?

To the Egyptians, it didn’t matter. Pharaohs often kept a full harem, and all of their children were legitimate.

The Black Cleopatra Theory

To us Cleopatra’s mother matters. Our own recent history makes us want to know whether Cleopatra was perhaps a powerful woman of color, unfairly maligned by the white men who wrote the histories. She was certainly most of that. But we just don’t know about the woman of color part. The ancient Mediterranean world was a multi-ethnic one. Romans disliked and distrusted foreigners, but that wasn’t about skin color. Southern Egyptians felt like the “true” Egyptians, while northern Egyptians were ever so much more sophisticated than their country cousins to the south, but that also was not about skin color.

In 3000 years, Egypt had absorbed groups from every direction, leading to a hodgepodge of skin tones and hair textures living side by side. Being Egyptian was about birthplace, culture, and religion. So even if Cleopatra’s mother was a native Egyptian, it tells us nothing about her race. None of her contemporaries considered her skin color important enough to write it down. We do know she was at least 25% Macedonian through Auletes. The other 75% is a mystery.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Gaining Power (Half of It Anyway)

Having established that we know very little about her race, we can move on to what we know about her childhood, which is nothing. The Ptolemies had nothing against educating and promoting women, so we assume she got a good education. In fact, the Ptolemies had an unusual tradition of equal co-rulers, with both a man and a woman. Cleopatra was a joint ruler with her father for the last few years of his life.

But the first real evidence we have of our Cleopatra doing things independently comes after Auletes’s natural death in 51 BC. In his will, he followed the Ptolemaic tradition and named her and her younger brother Ptolemy the 13th as co-rulers, with the good citizens of Rome as guardians and protectors of his line. Now this is hardly a power grab. She inherited! Legitimately according to the rules of her country. Well, she inherited half the power. But as you will see, half isn’t going to cut it for Cleopatra.

To follow the shining example of their forebears, the siblings should have married at this point and started producing the next generation. Now let’s pause here for a moment to consider. Getting married against your will is completely normal when you are a princess, but usually that means getting shipped off to marry a stranger who is anywhere from 1 to 51 years older than you, which is flatly terrifying. It usually does not mean marrying your snot-nosed, attention-stealing, tattle-tale brother who is 10 years old. I mean, Ew.

Cleopatra, age 18, handled it by simply ruling alone. Her name appeared first on proclamations, except when she forgot to mention his at all. So her first step at seizing power was simply to freeze out her co-ruler. It won’t be her last step.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Unfortunately, the 10-year-old’s advisers were not so ignorable. Within a couple of years, civil war appeared inevitable. Cleopatra had the support of the native Egyptians, but Ptolemy had the citizens of Alexandria, which held a major port, a lot of treasure, and the palace they had both grown up in. Cleopatra had been pushed out of the capital.

Rome Steps In to Save the Day (for itself)

Meanwhile, Rome had its own problems. In theory, they were republic and proud of it. In reality, dictatorship was up for grabs. When Caesar’s army trounced Pompey’s, Pompey fled to Egypt, hoping for Ptolemy’s support. Ptolemy’s advisers thought it was clear that Caesar was on the rise. They didn’t want to back the wrong horse. Pompey was welcomed courteously off his boat, at which point he was stabbed in the back and his head chopped off. His body they dumped, but they kept his head and presented it proudly to Caesar when he arrived four days later.

In the eastern tradition, the severed head of your mortal enemy was a great welcome gift. How pleased Caesar would be! Except that he wasn’t. Romans prided themselves on their battle prowess and civilized behavior. To stab an honorable enemy in the back was shameful. For a barbarian easterner to murder a Roman citizen was insulting. And presenting his head on a platter? Ew again. Oh, and by the way, Pompey also happened to be Caesar’s father-in-law. That’s a bit hard to explain to the wife.

Caesar wept openly at the sight of his head. Whether he was really as grieved as all that, we’ll never know, but it made a good show. Before the sun set, he had commandeered the palace, and Ptolemy’s hopes of Caesar supporting his sole claim against his sister’s were wobbling badly.

Caesar decided to play the statesman. He probably could have simply annexed Egypt, but instead he settled himself in the palace and determined that he would resolve the issue. It was, after all, his duty. Auletes’s will had charged the citizens of Rome with supporting his children. Julius Caesar practically was Rome. He ordered both pharaohs to appear before him. This was easy for Ptolemy. He was already there.

It was not so easy for Cleopatra. She would have to come through the hostile city of Alexandria, an easy mark for both jeerers and assassins. According to Plutarch, she accomplished this by hiding herself within the bedroll or rug of a merchant, who then smuggled her through the city and into the palace at night, where the bundle was dropped before Caesar to reveal the exotically alluring young woman, exactly as she planned. It’s a great spy story. It’s also a little hard to swallow. Was there no security checking up on unknown merchants with suspicious packages? Would a new bedroll have been dumped in front of Caesar himself, rather than a servant? Would a young woman with seduction on her mind want her victim’s first glimpse to be as she tumbled, disheveled and bruised, out of a rug?

Image Source: By George Shuklin – Own work, Public Domain

Cleopatra and Julius Caesar

However it was accomplished, she certainly arrived before Caesar in the evening. And he certainly did not find her too disheveled to be attractive. He was 30 years older than her and married. But who cares about that sort of thing? He had divorced one wife on the mere suggestion of her unfaithfulness, having said famously that “Caesar’s wife must be above suspicion.” He was married again, and he himself was above suspicion in the sense that publicly confirmed facts eliminate any need for mere suspicion.

When Ptolemy XIII, age 13, woke up in the morning, all his hopes were finally dashed. His sister was not only in city, she was in the palace. Caesar did not seem at all disposed to get rid of her. Ptolemy reacted with all the maturity and dignity that his 13 years had given him. He ran from the palace, tore off his diadem, and threw it at the ground in a public temper tantrum.

If Caesar thought he had stopped the war, he was wrong. Ptolemy’s armies attacked anyway. The fleet was burned, the palaces and library were burned, Caesar himself almost drowned. Ptolemy managed to persuade Caesar to release him on the promise of good behavior, and of course he broke his promise immediately. Cleopatra seems to have remained silent and inactive, at least according to the Roman sources. The struggle is quite clearly portrayed by the Romans as a struggle between Caesar and Rome on one side, with Ptolemy and the Alexandrians on the other. Right up until Ptolemy got himself drowned crossing the Nile, and that was the end of that.

Caesar reinstated Cleopatra, which has sometimes been used to further suggest that Cleopatra didn’t really do anything, and it was all down to Caesar. Which is a bit unfair, when you consider that she was actively leading one side of a civil war when he arrived. She made a valuable alliance, that’s all.

Either way, Cleopatra was back, with her even younger brother at her side, named—you guessed it—Ptolemy XIV. One source states that Cleopatra did marry this brother, lucky him. So her second step to seizing power was to fight off her first co-ruler, and then install an even more ineffective second co-ruler. Caesar could have dusted off his hands for a job well done and headed back out to Rome or further conquest, but he didn’t. He hung around. With Cleopatra. They took a pleasure cruise up the Nile through crocodile-infested waters.

Cleopatra gave birth to a son who was named—wait for it—Ptolemy Caesar, which is just a little hint that the prepubescent Ptolemy XIV might not have been the father. Neither Caesar nor Cleopatra recorded his paternity officially. Cleopatra didn’t need to. Her acknowledgement was all her son needed to be accepted by Egyptians. For Caesar life was more complicated. Romans wanted legitimate kids, and they didn’t believe in polygamy, and even if they had, it was illegal to marry a foreigner. This whole Cleopatra fling was an embarrassment. Why hadn’t he just annexed Egypt? How could their great and glorious leader have lost his head over a woman? Especially a debauched, despotic, corrupt, conniving seductress? Didn’t he see that she was making a fool of him?

In the summer of 47 BCE, Caesar left Egypt to go on a few more campaigns, which he won, of course, and by the following year he was settled back in Italy. Shortly thereafter, Cleopatra, her younger brother, and her son arrived and moved into Caesar’s own estate. Roman society was both appalled and fascinated. Cicero wrote passionately, “I hate the queen! . . . [Her] insolence. . . I cannot recall without indignation” (Tyldsley, 105). It was rumored that Caesar was planning to change the laws so that he could marry Cleopatra and acknowledge her son with his oh-so-unsubtle name.

Whether Caesar planned that or not, it never materialized. He was betrayed, stabbed, and killed. His will made no mention of Cleopatra or her family, but then again, it couldn’t have. It was illegal to leave bequests to foreigners.

We have no record of how Cleopatra felt about his death. There are hints that she may have been pregnant again at the time, but if so, she lost that baby. A double tragedy for her in a very short timeframe. If she had planned on becoming Empress of Rome, there was no hope for it now.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

But she was still pharaoh of Egypt, and in 44 BCE, she was back in her own country. Within months, Ptolemy XIV was dead. While there is no absolute evidence, it was generally assumed (both then and now) that she followed her family’s traditions and had him poisoned. He was getting to the age where he might have been troublesome. And she didn’t need him as a co-ruler anymore. She had a son to be her co-ruler. Also, by emphasizing her identity as a mother, she could step into the semi-divine role as the living Isis, a powerful image to both her Greek and Roman subjects. From pharaoh to goddess. There was no glass ceiling here. So her final and most complete method of power grabbing was: assassination.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Back Home in Egypt

Cleopatra ruled alone and competently for three years. Her position was secure and Egypt was at peace.

Rome was in shambles. Caesar’s death had brought, not stability, but a blame game. Naturally, all sides wanted Egypt’s support. After some hesitation, Cleopatra came out in favor of those seeking to punish Caesar’s murderers. She and her fleet set up to join them in Greece, but a combination of bad weather, seasickness, and (possibly) a desire to delay truly committing herself, sent them fumbling their way back to Alexandria. Brutus and Cassius were defeated anyway, and that left Octavian (Caesar’s adopted heir) and Mark Antony (Caesar’s long-time friend) both poised for total control.

Octavian was sickly, ill, and widely accused of cowardice. Mark Antony was older, healthier, more popular, and firmly in control of the Eastern empire. Who would you have backed? Cleopatra needed a powerful Roman to protect her claims to Egypt. Mark Antony needed money to pay his troops. It was a match made in heaven.

Cleopatra and Mark Antony

Mark Antony summoned Cleopatra to meet him in Tarsus. It is very likely that she knew Mark Antony already, and she may have known how best to handle him. She set sail as the living embodiment of Isis, in a gilded ship with silver-plate oars and a sail of purple silk. Musicians played on the deck. Incense wafted through the air. Cleopatra lounged under a gold-spangled canopy. Her attendants were small boys dressed as Cupids. The good people of Tarsus came down to the harbor to gawk. Mark Antony sat up in the center of town, waiting for her to arrive. More people went down to the harbor to gawk. He sent her an invitation to dinner. She countered with an invitation for him to come down to dinner. Finally, he could not sit around waiting for her any longer while his attendants slipped down to the harbor. He went to her. She won the first round.

As the Roman sources tell it, Mark Antony was a simple good-hearted country boy. The type who just couldn’t be expected to control himself in the presence of an experienced, duplicitous temptress like Cleopatra. He immediately—and I’m quoting here—“joined Cleopatra and the Egyptians in general in their life of luxurious ease until he was entirely demoralized” (Tyldesley, 150, quoting Dio).

Maybe, but this simple good-hearted country boy was also bent on dominating the Roman empire, and he needed her money. Maybe he was just hard-headed and ambitious. And not averse to feasting, drinking, and more sensual pleasures, which according to the Roman accounts, filled 100% of their time together. In one famous story, Cleopatra bet Mark Antony that she could serve him a banquet worth 10 million sesterces. She served an amazing array of food but topped it off by dropping her enormous pearl earring into a glass of wine and drinking it down. Historians are divided on whether this really happened at all, whether she knew that strong wine would dissolve a pearl to make it easier to swallow, and whether she drank it quickly in a bid to—shall we say?—recover it when it came out the other end.

When Cleopatra returned to Egypt, and Antony followed her. They enjoyed a winter together. Nine months later Cleopatra gave birth to twins, a boy and girl. Antony had already left Egypt. They did not see each other again for 3 ½ years. So either he wasn’t as lovesick as all that, or he was busy: the Parthians were attacking, several of Rome’s client kings had defected, and Octavian was eroding Antony’s support in Rome.

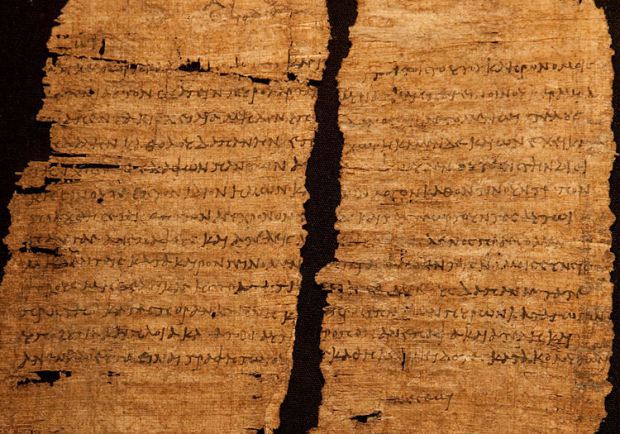

Meanwhile, Cleopatra presided over the country that was doing very well. It is during this period that a simple decree granting tax privileges was written. This papyrus document was later recycled as a mummy wrapping. In modern times it has been recovered, analyzed, and some experts believe that the words “let it be so” at the bottom are in Cleopatra’s own handwriting. If so, it is the only example of her writing that we have.

By 36 BCE, Octavian was beginning to get the upper hand. Antony needed money again. When he and Cleopatra met again, he gave her Cyprus, Crete, Libya, Phoenicia, etc. etc. etc. She didn’t get Judea, but she did get an excellent economic arrangement with them. Cleopatra was now the wealthiest monarch in the Western world. Antony also acknowledged his twins, who were grandly named Alexander Helios, the sun, and Cleopatra Selene, the moon. Nine months later, Cleopatra bore another son, Ptolemy Philadelphos.

Romans were appalled at yet another moral lapse, but he got what he wanted. Newly supplied with the Egyptian fleet and Egyption provisions, Antony turned to attack Parthia. It didn’t go well. He lost a huge number of men and was forced to retreat. Once again, Cleopatra was called on for help. And once again, they both recuperated in Alexandria.

In the western empire, Octavian scored several major victories. He also got to play up the way he was a virtuous, honorable citizen of Rome, while his poor much wronged sister (Mark Antony’s wife) was publicly humiliated by a foreign witch who preyed on other women’s husbands. Rumors of Cleopatra’s unnatural relationships with everyone from close relatives to neighboring kings to slaves to otherwise upstanding Roman citizens made the rounds, growing bigger with every telling. It is impossible to know for sure, but we have no evidence that she ever had a relationship with anyone beyond Caesar, and after his death, Mark Antony. Certainly the two of them can account for all her children.

Image Source: Classical Numismatic Group, Inc.

The propaganda war was in full swing. Roman citizens were told that Cleopatra made Mark Antony rub her feet like a slave. She had convinced him to abandon Rome and make Alexandria the capital of the empire. He was so under her power that she was going to use him to rule Rome itself.

Mark Antony was not above the mudslinging either. He accused Octavian of humble origins, being Caesar’s catamite, running away from battle, feasting during times of public hunger, and even—and this was really bad—using red hot walnut shells to singe away his leg hair.

When you are reduced to criticizing leg hair, perhaps war is inevitable. Marc Antony, Cleopatra, several consuls, and 300 loyal senators began assembling a fleet in Greece. The senators did not want Cleopatra to be there. They did not view themselves as supporting Egypt against Rome. They preferred to support Marc Antony against Octavian. Marc Antony refused to send her away, maybe because of infatuation, but more likely because she was experienced, intelligent, and the financial linchpin of the whole venture.

Octavian assembled his fleet in Italy. His preparations were substantially behind theirs, but if they attacked him first, the Italian population would see it as a foreign invasion. They certainly weren’t going to accept Cleopatra taking Rome by force. So they waited. It was not until late in 32 BCE, that Octavian was finally ready. The senate formally stripped Antony of all his titles. He stood before the temple of Bellona, goddess of war, and ritually declared war on Cleopatra (not Mark Antony). The justification, according to him, was all-encompassing, as it only said “for her acts,” which may be the most vague excuse in the history of warfare.

Things went badly for Cleopatra from the start. The omens were not in her favor, as demonstrated by an earthquake, statues being struck by lightning, and the like. In more practical terms, the supply lines were cut, malaria and dysentery struck, and morale was distressingly low. Many of the senators and soldiers defected to Octavian.

It was time for a new plan. All the most valuable possessions were loaded onto their best vessel. On September 2, 31 BCE, in the midst of a sea battle, Cleopatra raised sails on 60 ships and made a break for it. Marc Antony followed her with 40 ships. Octavian records that he killed 5000 of Antony’s men, and he took 300 of Antony’s ships. He also quickly caught the ground troops and bribed them to join his side, which can’t have been hard, given that they had nowhere else to go. What he missed, however, was the war chest with enough treasure to pay for this campaign. Cleopatra had saved that. Even so, the battle of Actium made the end inevitable.

The Final Battle

Cleopatra returned to Egypt, consolidated her assets, and made plans to flee before Octavian could arrive to follow up on his victory. Her plan was to make use of Egypt’s other coastline and escape by way of the Red Sea. Unfortunately for her, the Suez Canal would not be built for another 2000 years. So she needed her fleet to be transported overland. This was not unheard of. Previous pharaohs had done it. But going over land was a slow business, and her boats were attacked and destroyed by a client king wishing to please Octavian.

Increasingly desperate, Cleopatra sent her oldest son away overland to the Red Sea with half the treasury and instructions to flee to India. She moved the other half of her treasure into her mausoleum and surrounded it with flammable material. She preferred to burn it rather than give Octavian the satisfaction of seizing it.

According to Plutarch, Cleopatra also began to experiment with poisons, ultimately concluding that the bite of an asp was the quickest and least painful way to end her life should the need arise.

Meanwhile, Octavian was in touch. Cleopatra asked if she could abdicate in favor of her children. Octavian said she should kill Antony first, and then he would think about it. Antony asked if he could simply live as a private citizen. Octavian didn’t bother to answer. Cleopatra tried to bribe Octavian. He took the money and continued to advance.

Morale in the Egyptian camp was low. Cleopatra rewarded one brave soldier with golden armor. He deserted for the enemy the same night.

On August 1, 31 BCE, Antony led his troops out for a final stand. The Egyptian fleet sailed out to engage Octavian’s ships. Antony stood on firm ground and watched while his fleet approached the enemy. They drew close, ready to attack, and then turned around, raising oars to Octavian and joining him. The cavalry, witnessing this, deserted immediately. The infantry stayed, but what could they do against so many? And report came that Cleopatra had killed herself.

It was time. Marc Antony, knowing that all hope was lost, stabbed himself in the stomach so that he lay, writhing on the ground, when word came that Cleopatra had not killed herself after all. Oops.

What she had done was barricade herself in the mausoleum with her treasure. The doors were sealed. Mark Antony, still writhing, was hauled up the walls on ropes to enter through a window before dying in her arms.

Octavian was not pleased. He wanted Cleopatra alive so he could parade her through Rome as a living symbol of his victory. And he definitely could not afford to let her treasure burn. He had fully absorbed a point that so many future emperors would also realize: the key to being emperor is to pay the troops well. So at this point the battle was irrelevant. Everything depended on Cleopatra herself.

Octavian’s negotiator spoke with Cleopatra through a locked door. She refused to open it and begged for her children’s lives. While she was kept busy talking, another man used a ladder to enter the mausoleum the same window Mark Antony had entered. He crept up behind her and captured her.

How Octavian must have grinned. Mark Antony was dead. Good. Cleopatra was alive and captured. Good. The treasure was unburned and in his hands. Very good. Back in Rome, interest rates dropped from 12 to 4 % overnight.

Cleopatra was hustled from the mausoleum to the palace, where she grieved, stopped eating, and grew feverish. Octavian forced her to eat by threatening her children.

Depending on which Roman account you believe, Cleopatra was either practically dead with grief and blubbering about how everything was Mark Antony’s fault. Or she was still a charming siren who pulled out her old tricks and tried seducing her third powerful Roman. Only this time, Octavian, that model married man, showed his moral fortitude and refused her. Women have done many things to save their lives and their children, so maybe she did try, but Octavian’s moral uprightness is hard to square with his long history of affairs. A more likely explanation is that he simply had no need to ally with her the way Caesar and Mark Antony had. He had already won everything he wanted.

He did, graciously, allow Cleopatra to visit Mark Antony’s tomb. On her return to the palace, she sent a sealed message to Octavian and dismissed all but two servants.

In Search of an Honorable Death

The image of Cleopatra dying from the bite of an asp on her breast is so famous that it may come as some surprise to learn that her death is an unsolved mystery. The room was sealed. The only wounds were a couple of pin pricks on her arm. If it was an asp, where did it come from and where did it go? The Egyptian cobra, the most likely species, is over six feet long. Quite a thing to smuggle in safely. How did she convince it to bite her, and not only her, but also her two servants? Even if it did bite them all, a single snake doesn’t have enough poison to kill three adults. At least one historian has come to the conclusion that there never was a snake. Maybe she just used poison: easier to smuggle and far more certain to cause death.

However it happened, she was dead. 3000 years of history ended as Octavian annexed Egypt on August 31, 30 BCE. There is no denying the level of importance he attributed to Cleopatra. The month of July had been named to honor the birthday of Julius Caesar. The month of August was named for Octavian, who took the name Augustus. But he wasn’t born in August. It was, rather, the month that he defeated Cleopatra, the last pharaoh of Egypt.

Selected Sources

Sources on Cleopatra are both plentiful and contradictory. My personal pick is Joyce Tyldesley’s Cleopatra: Last Queen of Egypt

You can read Plutarch’s version of her in his Life of Antony. Plutarch was the major source for Shakespeare’s play Antony and Cleopatra. But do bear in mind that Plutarch was neither unbiased, nor an eye-witness. He wrote about 100 years after Cleopatra’s time. If an Egyptian had written an equivalent biography, I think it would have read rather differently.

You can also read one historian’s view of how she really died here.

[…] mentioned in this episode include Cleopatra, Draupadi, Jnanadanandini Devi, and Indira […]

LikeLike

Such an interesting story and so well told! I’m getting smarter every week!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] episode is a retrospective look at Cleopatra, Wu Zetian, Elizabeth I of Russia, Catherine the Great, and Ranavalona. I discuss a three-step […]

LikeLike

[…] mentioned include Athena, Artemis, Tyche, Astarte, Cleopatra, Fulvia, Octavia, Livia, Julia, Agrippina, Juno Moneta, Lakshmi, Elizabeth I, Empress Maria […]

LikeLike

What a dynamic story! Cleopatra certainly had possessed many of the same qualities that we both extol and despise in our modern politicians!

LikeLike

[…] fact, my sense of Elizabeth is that unlike Cleopatra and Wu Zetian, she wasn’t really cut out for absolute power. She was neither ambitious nor […]

LikeLike

[…] up by Julius Caesar, with the help of astronomers from Alexandria in Egypt, which means they were Cleopatra’s subjects, probably working under her patronage. The Julian calendar was a major improvement […]

LikeLike

[…] Women (and goddesses) mentioned include Elizabeth II of England; Rhea; Gaea; Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, Leah, Ruth and Mary from the Bible; Elizabeth I of England; Victoria of England; Isabella of Aragon; Maria Theresa, Holy Roman Empress; Empress Suiko; Pharoah Hatshepsut; and Cleopatra. […]

LikeLike

[…] Cleopatra, our first power-grabbing lady, seized power by freezing out her brothers. Wu Zetian did it by freezing out her husband and then her sons. Elizabeth of Russia did it by deposing her cousin. But what they all had in common was that they were actually citizens of the country they eventually ruled. They were born there, raised there, and everything. […]

LikeLike

[…] year is 42 BCE, and we are in Rome. If you remember episode 2.2 on Cleopatra, you may remember that Rome is theoretically a republic, but moving fast towards empire. Julius […]

LikeLike

[…] larger area was stuffed with strong women. Ptolemaic Egypt was currently ruled by Cleopatra. (Not that Cleopatra; this is an earlier one, Cleopatra III). The Seleucids had also had a queen regnant in living […]

LikeLike

[…] Cleopatra originally featured in series 2 on Women Who Seized Power. But she fits equally well in series 12 on The Last Queen. You can read the the transcript and see pictures on the original post. […]

LikeLike

[…] went back to Rome to tell the Senate how great he was, and many of them much agreed. Then he met Cleopatra, and the rest was last week’s episode. Britons went back to their lives. The difference was they were no longer off the edge of the Roman […]

LikeLike

[…] definitely remarried and that was probably only under orders of the caliph. And then there’s Cleopatra whose relationships are so complex they cause dizziness, but for sure she never allowed any of the […]

LikeLike