In 1988 when Benazir Bhutto became prime minister of Pakistan, the leader of the opposition said “Never—horrors!—has a Muslim state been governed by a woman!” (Mernissi, 1). It was unnatural, and therefore wrong.

Never is a long word and when used by politicians to describe history, you can pretty much count on it to be wrong. Today’s episode is about just one of number of times that a Muslim state has been governed by a woman.

The country of Yemen is on the southern end of the Arabian peninsula, and as such it has a long and glorious history of being ignored by Islamic scholars because the real action was happening in places like Mecca and Baghdad and Cairo.

Speaking of Baghdad and Cairo, those were the two cities dominating the Islamic world in the eleventh century when Arwa was born. Over in Baghdad the ruler of the Abbasid Empire was the caliph, a title which meant he was both the political and religious successor to Muhammad. As such he was the one and only supreme leader of the Muslim world. Meanwhile in Cairo, the ruler of the Fatimid empire was also the caliph, also the political and religious successor to Muhammad, also the one and only supreme leader of the Muslim world.

As you can imagine, the situation was a little tense.

The Sulayhid Dynasty

The king of Yemen, named Ali al-Sulayhi, was allied with the Fatimids. They liked him because he provided them with a direct trade route to India (Traboulsi, 98). He liked them because this way he didn’t have to pay taxes to Baghdad, which had no need to go through him to get to India (Mernissi, 128). Those were the economic reasons anyway. Al-Sulayhi’s motivations might also have been religious. The Fatimids were Shiites. The Abbasids were Sunni.

Whatever his primary motivations, Ali al-Sulayhi was a powerful leader. He conquered Mecca, which is certainly one way to get the attention of the Muslim world. But he did have enemies, even at home.

In 1066, he went on a grand (and I mean really grand) pilgrimage to Mecca. Thousands of people went along, including his wife Asma.

Unbeknownst to them all, an assassin was also present: Said Ibn Najah, who killed the king, imprisoned the queen, and displayed the disembodied head of the king so that it was visible from her cell (Mernissi, 146).

Back at home, the crown prince Ahmad al-Mukarram was running the show. I would imagine he heard about the death of his father pretty quick, but it was some time before he knew his mother was still alive. At least a year. When he did know, he brought 3000 horsemen to rescue her and he succeeded. But when he entered her cell his grief and shock and new responsibility were so much that they overcame him. Ahmad collapsed in a heap, partially paralyzed, and Asma had to bring back the inert body of her son. He never recovered the full use of his body (Mernissi, 146).

Or so goes the story. If you ask me (and some other accounts) something is missing from that story. Like maybe a battlefield injury. A bout with polio, perhaps? There are loads of reasons why a person might suffer permanent paralysis, but emotional distress just doesn’t seem like enough of a cause.

Asma (Ahmad’s mother) was an impressive woman, famous for attending councils without a veil. And according to some accounts, she too was a Queen Regnant, though that’s debated for several reasons. But even if she wasn’t, her presence as a strong leader was definitely watched by her daughter-in-law, Arwa.

Arwa Takes Power

Arwa al-Sulayhi grew up in the palace. She was the niece of Ali and Asma’s, and she was an orphan, so they took her in. When she was 17 or 18, they married her to their son Ahmad, crown prince at the time, and gave her a fantastic dowry of the coastal city of Aden (which is still a city today) (El-Azhari, 225). She managed Aden herself, according to one of my sources (Mernissi, 147), though that is not usually how a dowry works. If so, it was undoubtedly great experience for future needs, though probably no one realized it at the time.

In 1074, Asma died, which shouldn’t have made much difference, politically speaking. Her son Ahmad was already holding the throne. But it was also in 1074 that the partially paralyzed Ahmad officially delegated all powers to his wife Arwa (El-Azhari, 226). Quite honestly, it’s astonishing that he had any powers to delegate. Disabled kings often find it quite hard to hold onto their thrones because fairness and accessibility were not really the top considerations. Really, they weren’t considerations at all.

The generally accepted solution is that Ahmad survived because he had some truly extraordinary women around. First, his mother ruled, and now his wife will.

Arwa did plenty of political things, like moving the capital (El-Azhari, 228) and negotiating alliances (Mernissi, 148). But in the overall historical sense, the most startling thing she did is one that maybe doesn’t sound so earth shattering to us. She had her name proclaimed in the khutba, or the weekly prayers and preaching at the mosques. A queen’s name was generally not included here. In fact, some sources say Arwa and Asma are the only queens to have ever had their name proclaimed in khutba. Which is not quite true, but almost.

The exact wording of what was said every week in the mosques was “May Allah prolong the days of al-Hurra the perfect, the sovereign, who carefully manages the affairs of the faithful” (Mernissi, 116).

Al-Hurra there is a title given to women of high status. Longtime listeners of this show may remember Roxelana, the Ottoman queen, episode 4.3? She was also called al-hurra.

Thus far Arwa is ruling as Queen Consort, rather than as Queen Regnant. But there’s no doubt that everybody knew who was running the show in Yemen. The caliph in Cairo acknowledged as much in a surviving letter to her. He said that his vizier, “God bless him, keeps reporting to our eminence how you (Arwa) are the guardian of the believers, male and female, in Yemen; how you are keen to keep the orderliness of religion, until the banners of truth shine. As a result, the followers are organised in their obedience to the Alawite (Fatimid) state. And as a result, the commander of the faithful has issued this letter to you, to honour you and distinguish you among your peoples. Do exaggerate in enforcing your justice in Yemen, so your news can spread around to the furthest of corners” (El Azhari, 231).

Notice how there’s no mention there of her husband.

In 1084, the situation changed though because Ahmad died (El-Azhari, 231). In a perfect world, no upheaval would be necessary. Arwa was already running things, so it should be business as usual. But of course it isn’t a perfect world, and this was grave cause for concern

Arwa’s son was the obvious successor, but he was still young. Meanwhile there was a very capable cousin, Prince Saba’, and an equally capable assistant al-Zawahi, both of whom thought they were up to the job of being king. Some accounts even have Ahmad leaving the Kingdom to Saba’ in his will (El-Azhari, 231), though it is unclear to me why he would bypass his own son.

Arwa was having none of that, obviously, so she concealed Ahmad’s death. For a year. A year!

Wow. I mean I suppose as a partially paralyzed man who had delegated power to his wife, Ahmad might not have been making many public appearances, but still. There must have been people who knew, and it’s crazy that nobody leaked it.

The value of waiting to make the announcement may have been so that her son was older. But mostly it was so that the caliph in Cairo had time to write saying that he approved Arwa’s son as the next king with her as regent. Not only that but he told all believers that it was their religious duty to obey her. And he elevated her to the religious rank of hujja, which meant not just secular authority, but also religious authority, second only to the caliph himself. For a woman to attain such a rank was unprecedented as far as I am aware (El-Azhari, 231-232; Traboulsi, 101).

That was the moment for a general announcement about Ahmad’s death.

Prince Saba’ seems to have accepted this because he knew there were other ways to get the throne. Like marriage. There is no doubt the Arwa married him. What is in doubt is why. In some accounts it’s because the caliph told her to (El-Azhari, 232). In others Saba’ proposed to her and she accepted. Or he proposed and she refused, and he laid siege to her castle until she agreed. Or he proposed and she refused, and then the caliph paid an astronomical dowry to convince her (Mernissi, 155).

However it began, they were married for eleven years and never had any children. Possibly because she said she might have agreed to a wedding but not to anything else. There has been far more discussion of whether that marriage was ever consummated than I think the question deserves.

So moving on. She’s still not a queen regnant, but Saba’ isn’t the one ruling. Cairo continued to direct their letters to her, not him (El-Azhari, 233).

In 1088, Arwa made her move against the dissident group that had killed her father-in law, and she was clever about it too. She ran a campaign of disinformation, drawing out her enemy by making him believe that her allies were deserting her. Said Ibn Najah fell for it. His army moved in for the kill, and Arwa was much, much stronger than he had bargained for. The circle of vengeance was complete when Arwa took Said’s wife prisoner and displayed Said’s severed head within view of the cell (Mernissi, 148). I’d like to say this part is tidy, symmetrical fiction on the part of the chroniclers, and it might be. But it also could be tidy, symmetrical vengeance on Arwa’s part. It was a different world back then.

No Male Figurehead in Sight

Now my chronology gets a little confused here, and I think that’s the source’s fault, not mine. But in some unspecified order, Saba’ died and Arwa’s son died and her younger son died, and there she is, still ruling Yemen with no male figurehead in sight.

One inescapable fact about rulers in general and female rulers in particular is that they tend not to last that long. The pre-modern world had plenty of perils for any human beings, and heads of state also had enemies they knew about, not to mention the enemies they didn’t know about. But Arwa had now been holding the reins of power for four decades.

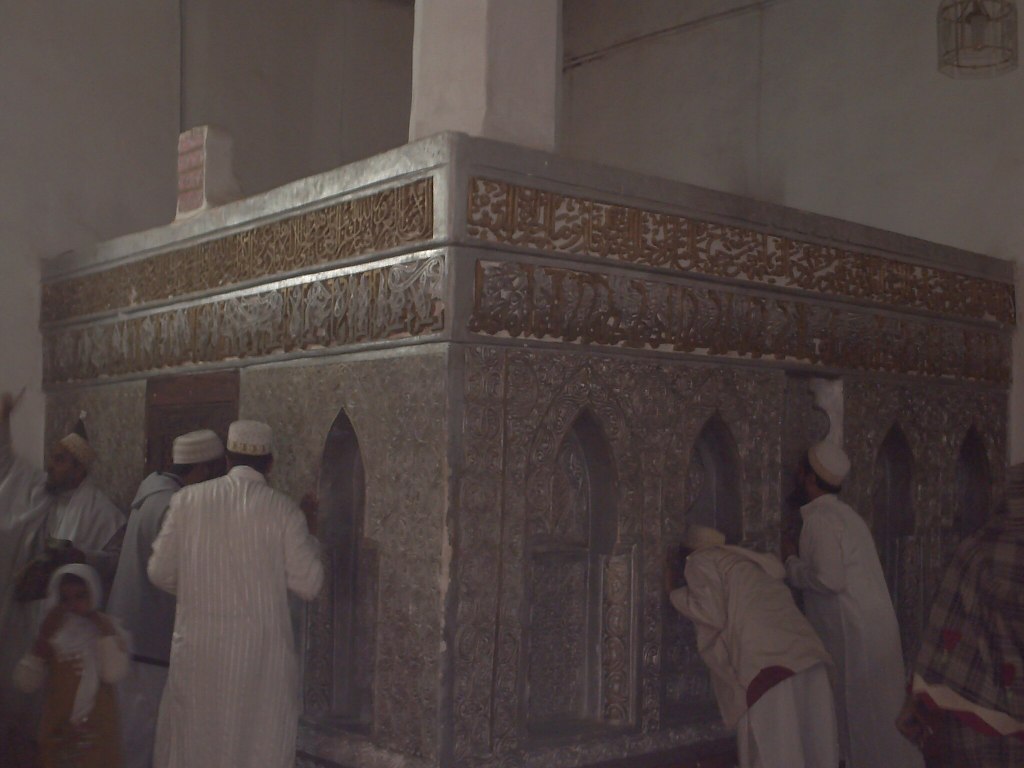

During that time, she built roads and mosques, at least one of which is still there in Sanaa. She also led the army on at least one occasion, successfully restoring a rebellious citadel (El-Azhari, 236).

In 1119 a new caliph in Cairo was an unsettling development. He sent a man over to Yemen to “advise” Arwa, possibly at her request (El-Azhari, 236), possibly to her disgust (Mernissi, 157; Traboulsi, 103). He hung out in Yemen for six years, mostly making trouble, and in 1125 Arwa got tired of him and sent him back to Cairo. On the way, the ship foundered and he drowned. Some say the captain scuppered it on purpose under orders from Arwa (Traboulsi, 103). But if so, then she was also willing to sacrifice a trusted advisor and the gifts she had sent the caliph on the same ship (El-Azheri, 237). Could be a good cover story. Or could not be. There continued to be trouble from Cairo because Cairo itself was having trouble settling who the new caliph should be, and Arwa did not back the winning candidate. For the last seven years of her reign, she continued to rule without the support of a caliph (El-Azhari, 239). Purely on her own authority.

In 1138, Arwa died of natural causes, which is, in the words of one of my sources, “something of a miracle for an Arab sovereign” (Mernissi, 157). She had ruled her country for 64 years, and most of it she had done as both the nominal and the de facto head of state. There are some monarchs in history who beat that, but not many.

How to Explain Her Success

How to explain her success is difficult now and was even more difficult then. There were indeed many who said that a woman could not inherit authority (Mernissi, 157). Period. Some of them were even Fatimids, which is ironic because the name of their dynasty came from Fatima, daughter of Muhammad. She was also his only surviving child and the initial split that later divided Islam into Sunni versus Shiite was over whether her son could inherit authority through her. The Sunnis said no. The Shiites said yes. Hence the Fatimid dynasty, who claimed to be descendants. Didn’t stop them from looking askance at women in power.

Ultimately, the real reason the Fatimids accepted Arwa was probably because she was keeping the peace in a distant province they needed. Meanwhile, they had other problems. Some were internal dynastic squabbles. The others were Crusaders. It is during this same period that the First Crusade brought Northern and Western Europeans to the Islamic world bent on conquest.

What seems stranger than Fatimid support is that the Yemenis accepted Arwa. Or at least enough of them did that she was able to keep down the ones that didn’t. The average Yemeni was probably happy enough with whoever in power so long as they felt fed and safe. But scholars do worry about less practical things and one of them found an ingenious theory to explain the unexplainable regarding Arwa. He said (and I quote):

The human bodily envelopes are not vitally important, and are not the real indication of a person’s gender, but their deeds which generated from their souls. We can see some who appear in female envelopes, and occupy the most honourable ranks, like Fatima [daughter of Muhammad] … We also see other cases of some appearing in female envelopes, who are despicable. The male and female, who appear in the bodily envelopes do not reflect their true substance. It is only their deeds which guide us to determine their gender. Therefore, if a woman appears in a female envelope, yet she achieved all good and praised deeds, she is actually a male, enveloped in a female body. On the other hand, if a male appears in a male envelope, and shows no merits and excellence, in this case he is definitely a female. Men and women are not what appears in the bodies … but classified only according to their benefits and good deeds.

Al-Sultan al-Hattab, quoted in El-Azhari, 240, and Traboulsi, 105

Arwa, this scholar goes on to say, was really a man because she did good things. So that’s all right then (according to him). That explains everything, and all is well in his patriarchal world after all.

I could comment here. But honestly, even I am sort of at a loss for words.

Or wait a minute. No, I’m not. We live in a modern world that is struggling to define gender in a way we can all agree on. But I hope we can all agree that defining anything good as male and anything bad as female? That isn’t it.

After Arwa’s death, Yemen fractured. The men of her family were all dead, so the Sulayhid dynasty was over. Multiple lords claimed rule over bits and pieces of it until a Kurdish dynasty came in from the north to conquer.

Selected Sources

El-Azhari, Taef. Queens, Eunuchs and Concubines in Islamic History, 661-1257. Scotland: Edinburgh University Press, 2019. Chapter 4 online at https://edinburghuniversitypress.com/pub/media/resources/9781474423199_4._Fatimid_Royal_Women_and_Royal_Concubines_in_Politics.pdf

Kamaly, Hossein. History of Islam in 21 Women. Oneworld Publications, 2020.

Mernissi, Fatima. The Forgotten Queens of Islam. Translated by Mary Jo Lakeland, Minneapolis, University Of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Traboulsi, Samer. “The Queen Was Actually a Man: Arwā Bint Aḥmad and the Politics of Religion.” Arabica 50, no. 1 (2003): 96–108. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4057749.

Feature image by Mufaddalqn, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

[…] obviously yes. Because Aceh already had been for 48 years by this point, and let’s not forget Arwa from last week. There are other cases too. Besides all that, there’s the fact that even […]

LikeLike