Last week we left Marie Antoinette in the year 1789, as she and her family were carted out of their home in Versailles and taken to Paris, with the heads of their bodyguards traveling beside them on pikes.

The royal family was installed in the Tuileries, which was a palace, but no one had lived in it for decades. It didn’t even have furniture (Fraser, 302). They had a contingent of guards, but it was an open question whether said guards were there to protect the king and queen from the mob? Or were they there to protect the mob from the king and queen?

The man leading these guards was the Marquis de Lafayette, known to American fans as the French hero who helped George Washington win the American Revolution. He was now back at home working in much the same line of business. Lafayette wasn’t a radical. He favored a constitutional monarchy. (As did King Louis, I might add. Honestly, the French could scarcely have found a less tyrannical tyrant to revolt against. But the system itself was broken, and he was the public face of it, much to his own disappointment.)

Lafayette bluntly told Marie Antoinette that he would prioritize the survival of the Revolution over the survival of the king (Hardman, Marie Antoinette, 198). So that’s fun to live with.

Searching for Solutions

As Louis sank further and further into depression (Fraser, 320-330), Marie Antoinette looked about her and realized that if anyone was going to fix this hellish situation, it was going to have to be her. And she certainly tried, on multiple fronts. She was aware that the royal family needed a PR overhaul, and they needed it fast. The Tuileries gardens were opened to the public every afternoon. This pampered queen, who had only ever associated with the highborn (or at the absolute worst, the upper middlish born), went out and mingled with the great unwashed. She talked to soldiers. She shook hands with fishwives. She kissed orphan babies (Hardman, Marie Antoinette, 200).

On the political front, she worked with Revolutionary leaders to achieve some future in which both France and the monarchy would survive (Fraser, 313). The trouble was that the Revolution was a many-headed monster. Like others before and after them, the French had discovered that it is far easier to tear down the old system than it is to build a new one. Fiery men delivered passionate speeches and made promises that were more imaginative than they were practical. Everybody cheered until things didn’t turn out as promised. Then, off with his head, and he was replaced with another fiery man delivering passionate speeches.

Besides the problem of who do you even talk to in all this chaos, there was the problem that when you negotiate from inside a prison, you’re not in a strong position to demand anything.

They needed freedom of action, and again it was Marie Antoinette, who worked with multiple confederates to plan their escape. This prison break was complicated by the fact that it wasn’t just about getting out. They fully realized that if Louis had to sneak out of his own kingdom for his own protection, if he fled his own country, deserted France in its time of excruciatingly obvious need … well … it was going to be even more difficult to pretend that he was actually king of anything. So they settled on escape from Paris, yes, but not escape from the country. They would go to a fortress where the king could regroup and gather the faithful.

One of Marie Antoinette’s co-conspirators on the escape plan was Count Axel Fersen, a Swedish man who had been hanging round the French court for some years now. Marie Antoinette writers love to debate whether he was Marie Antoinette’s lover, and if so when did they first do the dirty, and how many of her four children were his. I have not mentioned Fersen before because I find the whole debate medium-pointless. As I’ve said before about other historical gossip, we really can’t know without a time machine and a paternity test.

So, yes, Fersen and the queen wrote letters to each other with terms of endearment (Imbler). Yes, I think if Marie Antoinette had been free to choose her own partner in life, she would have chosen Fersen. But she wasn’t free. And how stupidly short-sighted would she have been to risk having an illegitimate child? Especially before she had produced the required heir and the spare in the above board and legal way. I grant you that there is a significant overlap between people in love and people who are stupidly short-sighted. Even so, Louis accepted all four children as his. So did the country of France. That’s good enough for me. Back to the narrative.

Flight to Varennes

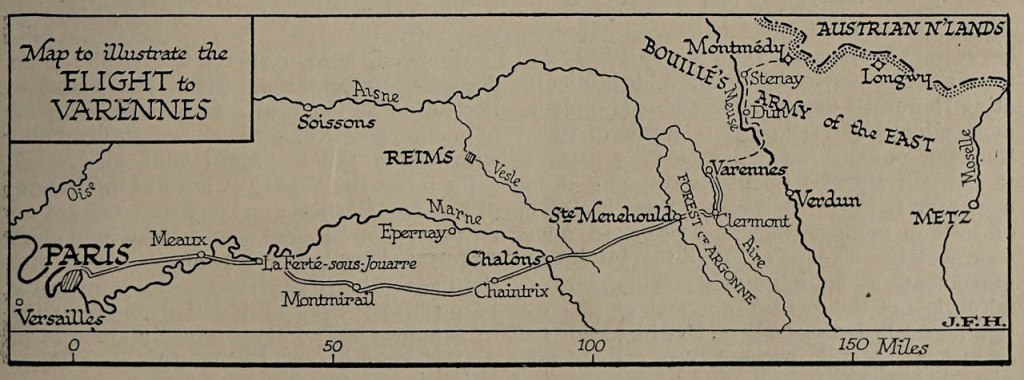

On the night of June 20-21, 1791, Fersen ordered a carriage brought round near, but not in, the Tuileries. Leaving separately at staggered times, Louis, Marie Antoinette, both children, their governess, and Louis’s sister Elizabeth all walked out of the grounds and in disguise. Marie Antoinette left last and she walked right past Layafette’s carriage without being stopped (Hardman, Marie Antoinette, 217; Fraser, 330-340).

I’m sure it was heart-thumping, but compared with fictional escapes where you somehow dig a tunnel through solid rock with a spoon, it sounds sort of easy. You sort of wonder whether Lafayette was really giving this job his best effort. And as you’ll see, I’m not the only one to wonder that.

The escapees met up at the carriage, and Fersen himself drove them out of Paris. The governess posed as Baroness de Korff. Marie Antoinette posed as the governess, Louis as a steward, and the crown prince as a girl. No one stopped them.

They drove through the night and the next day, which deserves some explanation in our world of modern transport. You can’t really drive straight through because you must stop to change the horses. Also, there are no pre-packaged shelf-stable finger snacks or coolers full of bottled water and soda. Also, every municipality reserves the right to challenge you, as you might be the kind of riffraff they don’t want in their town. Every time they got out of the carriage for any of these reasons was a chance they would be recognized.

Louis had sent ahead to have troops stationed along the route, even though he had been warned not to. His point was that they needed bodyguards. The naysayers’ point was that the troops were a bit of a giveaway to anyone in pursuit. A couple of people did recognize Louis. But they were monarchists, so they didn’t let on.

Until they got to Varennes in the second night for our escapees, or about a 3-hour drive from Paris at modern speeds. Varennes was a little speck of a place, too small to have a relay station with horses waiting for anyone who needed a change. Which is why the escape plans had arranged for a private transfer. Only their contact could not be found. By now they knew their escape was known, guards were possibly closing in fast, and Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, the king and queen of France, were reduced to going door to door, begging anyone they saw for horses (Hardman, Marie Antoinette, 219; Fraser, 333-349).

Their disguise could not hold up to that. At first, Louis denied that he was king. Arguments broke out and possibly a little rough handling as an interested crowd gathered. When it was clear that denial would not save them, Marie Antoinette silenced everyone by declaring that “if you recognize him as king then at least show him the respect to which he is due” (Hardman, Marie Antoinette, 220).

It was a last ditch effort, and it seemed it might work. There were tears and embraces on all sides. But the local authority was scared silly. He knew full well that somebody would be showing up soon to recapture the king, and said somebody was not going to be pleased if the growing crowd said yeah, we had the king and there’s the man who let him go!

The arguments and the debates went on for hours, while armed men on both sides of the revolution showed up in droves. Someone proposed that the king mount up, grab up the crown prince, and make a break for it. That would have meant leaving his wife and daughter in the hands of bloodthirsty fiends, but who’s really important here, right? When presented with that plan, Marie Antoinette did not object on grounds of chivalry or self-interest. But she was afraid that her son would be shot as they fled, so that plan was scrapped, and when an eager officer with 60 dragoons asked Louis for his orders, Louis said bitterly, “I am a prisoner and have none to give” (Hardman, Marie Antoinette, 221; Hearsey, 148).

The plain fact was that Louis did have soldiers who were still loyal to him, and another man might have attempted a fight or that mad dash on horseback. Either plan had a small chance of success and a significantly larger chance of going down in a blaze of glory, later to be made into a blockbuster movie.

But he was not another man. Louis was fundamentally decent and not at all swashbuckling. He wrote to an officer waiting just outside of town that he did not want to rule by violence. He tamely got back into the carriage, which began its slow drive back over every inch of the way to Paris and captivity.

It quickly became clear that he was also going to not-rule by violence. The closer they got to Paris, the more of a mob they attracted. People were butchered right before their eyes and for no clear reason. It seemed that reason itself had fled France. Only fear was left.

Imprisoned Again

Some in the National Assembly had been secretly glad the royal family escaped, but they were going to take no chances on getting the blame for it a second time. Back in the Tuileries, Marie Antoinette had guards in her bedroom, even at night (Hardman, Marie Antoinette, 232).

As Louis sank still further into depression and inaction, Marie Antoinette continued to feverishly write to various powerful men, trying to find a role for a king in a new government that was still making things up as they went along.

You may have been wondering didn’t she have a very powerful ally outside of France? Her brother, the Holy Roman Emperor, now also the Archduke of Austria, plus a lot of other fancy titles I won’t bother mentioning? What could he do for his sister?

That was a good question. Austria’s interests were not at all clear.

Emperor Leopold was a pragmatist. (The Emperor Joseph I mentioned last week had died without having a son; Leopold was a brother.) Leopold felt that if he got involved in a war in France to his west, then Catherine the Great of Russia would take advantage of him in the east. Plus, like all the other great powers, he was not exactly sorry to see France self-destructing, thus eliminating itself as a threat in Europe. (You can tell he hadn’t yet dreamed up the possibility of a Napoleon.)

Also, he had not seen his sister in fifteen years, and war is expensive. What would it actually accomplish? More territory for Austria? Marie Antoinette wasn’t offering half her kingdom or really any of her kingdom. She still hoped to maintain France with Louis as king. So basically, the only thing Leopold gave his sister was advice (Fraser, 311).

Even from Marie Antoinette’s point of view, Austrian help would be a tricky thing. If Austria conquered any part of France, they would be the evil invaders, and any French royals in league with evil invaders would be traitors. Therefore, death. If Austria did not conquer and merely attempted a prison break, the chances were good that the French would figure out what was going on before they arrived. The easiest way to deal with that would be to kill the inmates. Therefore, death. There were no good answers here. All of the bad ones were explained at length in a correspondence that she could only carry on by using code and invisible ink and scraps of paper sewn into hat linings (Hardman, Louis XVI, 212). It was hopeless.

Even now, at this late date, there were many who would have flocked to a king who presented himself as a leader, but instead they had a king who had never been a strong personality and certainly wasn’t now. A despairing Marie Antoinette told her lady in waiting that

Louis “is frightened to give orders and more than anything he fears to address a gathering … in the present circumstances a few well-articulated words addressed to the Parisians who are loyal to him would centuple the strength of our party. But he won’t say them. For my part I could be well content to mount a horse if need be. But if I acted it would only serve to give ammunition to the king’s enemies. Clamours against the “the Austrian” and the domination of a woman would be heard throughout France. Moreover I would unman the king by putting myself forward. A queen who is not a regent must in these circumstances do nothing and prepare herself for death.”

(quoted by Hardman, Marie Antoinette, 275)

In this judgment, she was quite right. Many of the things written about the royal family did blame her for every bad decision. The king was maybe all right, they said, but he was weak and manipulated by his evil wife (Fraser, 279-280).

By now she and Louis were taking it in turns to sleep, so the other could watch for assassins. They had not yet realized that assassins were not as big a threat as the new republic’s justice system.

On August 10, 1792, a mob broke into the Tuileries and butchered the Swiss Guards who were there to defend it (Hearsey, 181). The royal family fled to the Legislative Assembly, who were revolutionaries themselves, but also terrified of the mob.

After a standoff of several days, the family was transferred to the Temple, which was an actual prison, and not a gilded one like Tuileries had been. The guards there addressed Louis as Monsieur, not Sire. He was no longer king, though the formal dissolution of the monarchy would not come for another few weeks.

The Death of the King

Louis remained in custody with his family until December, when he was removed in order to stand trial. He was charged with “conspiring against liberty,” whatever that means (Hardman, Marie Antoinette, 288). True to form, Louis answered mostly in monosyllables. They found him guilty (Hardman, Marie Antoinette, 295).

He was allowed to see his family one more time and then he was taken away to be executed. Marie Antoinette learned she was a widow from the sound of the cannons that accompanied the fall of the guillotine blade.

The violence (and the fumbling government) raged on, but nothing changed for Marie Antoinette until July 3, 1793, when guards came to confiscate her son.

He was eight years old now, and she recognized him as Louis XVII, even if the government of France didn’t. Actually, the government of France was worried about that very thing, and it is amazing to me that they didn’t just kill the kid. That would have been fairly easy. What they did instead was worse.

The prince was given to the care of a man whose explicit job was to “educate” him. By educate, they meant corrupt. This had a two-fold purpose. Should anyone ever try to put him on a throne, he would never be fit to rule. Secondarily, they wanted him to testify against his mother.

So he was given hard liquor to drink and pornography to read. He was trained to swear and to blaspheme, and there is no doubt that all of this was enforced with physical violence (Hardman, Marie Antoinette, 219).

The Trial

On October 14, 1793, the trial of Marie Antoinette began. Bear in mind that most of the correspondence in which she had contemplated treason with her brother Leopold was unknown to the prosecution. She had burned all her copies and historians know about that mostly from the copies found in Vienna and Berlin.

But she was accused on various points like spending too much money on her personal palace the Trianon. (That was true, but not a crime.) She was accused of colluding with a minister to exhaust the treasury. (That was false; she had opposed that particular minister.) She was accused of victimizing Jeanne de Valois in the infamous necklace affair. (The one was false; the criminal victim relationship there ran in precisely the opposite direction). See last week’s episode for full details.

All that was just a warmup. She was accused of sending millions of francs to her brother Joseph back in 1785, of having sent military secrets to the enemy, and having set alight civil war. Not one piece of documentary evidence was presented about any of this (Hearsey, 234), and though she was given a lawyer, they were given only one day’s warning to prepare his case. Nevertheless, Marie Antoinette answered the questioners well. For example, when they accused her of deceiving the people of France, she said “Certainly the people have been deceived and cruelly so but neither by my husband nor myself but by those who had an interest in doing it.” (Hardman, Marie Antoinette, 298).

And then they brought in her son, age 8, for questioning before her. It began innocently enough. He was asked about the flight to Varennes, which, yes, he remembered. And was Lafayette in on it? The boy said yes.

When the prosecutor pointed out to Marie Antoinette that she had said the exact opposite, she said coldly that “it is very easy to make a child of eight say what you want.” (Hardman, Marie Antoinette, 303)

And nothing would prove the truth of that statement more than what followed. You see, the prosecutor was afraid his case was weak (and he was right). So he decided to go on a smear campaign. Character assassination of the worst possible sort

In what may have been the cruellest moment of what had been a long four years of cruel moments for Marie Antoinette, the prosecutor got the young Louis (who was eight) to say that his mother had taught him to masturbate and also that she had committed incest with him.

Marie Antoinette had by this point faced the possibility of personal assault more times than I had time to recount in three episodes. Practically everything had been taken from her, including her husband and her friends. Through it all, she had remained the one who made plans and looked for solutions. But this last accusation stunned her to silence.

When the court insisted on an answer, she said, “If I did not respond, it was because it would be against nature for a mother to reply to such an accusation. On this I appeal to all the mothers who may be here” (Hardman, Marie Antoinette, 304).

Marie Antoinette was found guilty on all counts and sentenced to be guillotined the following morning (Fraser, 436).

Even her own body betrayed her. She had suffered severe menstrual hemorrhaging before, and she did again on her final night. In the morning, October 16, 1793, she was dressed in white and carried out in an open cart to the Place de la Concorde.

The famous painter Jacques Louis David was in the crowd. He drew a rough sketch of her on her way, and it is worlds away from the pink and fluffy paintings of her youth. His sketch shows a straight-backed woman of courage, but ill and old. She was actually only 38 years old (Fraser, 439).

Not the Last Queen After All

In his autobiography, Thomas Jefferson, the American president and former ambassador to France, wrote that “had there been no queen there would have been no revolution” in France (Jefferson, 149). Jefferson often had good insights, but this is not one of them. It ignores the fact that France really did need reform, that the financial situation really was untenable, and that the largest reason it was untenable was the amount France had spent on the American Revolution, of which Jefferson himself was a top beneficiary. The queen had nothing to do with any of that. Her expenses were minuscule in comparison.

But Jefferson’s view was emblematic of what the French themselves believed. Everything that went wrong (and I do mean everything) was somehow her fault. They imagined her as an evil and scheming woman who dominated her husband and cared for nothing but her own pleasure. In fact, she was just a wife who had overspent her household budget. (Haven’t we all from time to time?) Yes, she was a stronger personality than her husband. (Legally that wasn’t a crime either, though socially it was.) She certainly didn’t dominate him in early life, and if she took a more active role later, it was mainly because he had either given up or was mentally ill. What else is a wife to do under those circumstances? Marie Antoinette did everything she could to protect her family. Her tragedy is that none of it worked.

You won’t be surprised to hear that the death of Marie Antoinette did not magically fix the problems in France. What was later called the Reign of Terror wasn’t over. The people of France tried several more forms of government, all of which worked out badly in the end, until eventually they decided that maybe a monarchy was okay after all. They could not have Louis XVII, Marie Antoinette’s son, because at age 10, he died of the treatment his “educators” gave him. So the French got Louis XVIII, the younger brother of the Louis who had been guillotined. Then a few more kings after that, until they again decided that actually a king wasn’t necessary after all. These kings had wives, so yes, Marie Antoinette was technically not the last queen of France. But she certainly had every reason to think she was.

Selected Sources

Fauchard, Pierre. Le chirurgien dentiste. France: Chez Jean Mariette, 1728. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Le_chirurgien_dentiste/BjBSAAAAcAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Faÿ, Bernard. Louis XVI, Ou, La Fin d’Un Monde. Translated by Patrick O’Brien, London, W.H. Allen, 1968.

Fraser, Antonia. Marie Antoinette : The Journey. New York, Ny, Anchor Books, 2002.

Hanley, Sarah. “Configuring the Authority of Queens in the French Monarchy, 1600s-1840s.” Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques 32, no. 2 (2006): 453–64. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41299380.

Hardman, John. Louis XVI. New Haven, Conn Yale Univ. Press, 1993.

—. Marie-Antoinette : The Making of a French Queen. New Haven, Yale University Press, 2019.

Hearsey, John E N. Marie Antoinette,. Sphere Books, 1972.

Imbler, Sabrina. “Marie Antoinette’s Letters to Her Dear Swedish Count, Now Uncensored.” The New York Times, 1 Oct. 2021, http://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/01/science/marie-antoinette-letters.html.

Jefferson, Thomas. Autobiography of Thomas Jefferson, 1743-1790: Together with a Summary of the Chief Events in Jefferson’s Life. United Kingdom: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1914. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Autobiography_of_Thomas_Jefferson_1743_1/5lG7ISgjvr0C?hl=en&gbpv=0

Nancy Bazelon Goldstone. In the Shadow of the Empress : The Defiant Lives of Maria Theresa, Mother of Marie Antoinette, and Her Daughters. New York, Little, Brown And Company, 2021.

Padover, Saul Kussiel. The Life and Death of Louis XVI. D Appleton-Century Company, 1939.

Sanson, Henri. Memoirs of the Sansons, from Private Notes and Documents. 1689-1847. United Kingdom: Chatto and Windus, 1876. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Memoirs_of_the_Sansons_from_Private_Note/ZZdIAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjkstSj-aWFAxWEAHkGHYylC0AQiqUDegQIDRAG

Timms, Elizabeth Jane. “When Mozart Met Marie Antoinette?” Royal Central, 5 July 2020, royalcentral.co.uk/features/when-mozart-met-marie-antoinette-133508/.

“She was 38.” This made me tear up. She died only a year younger than I am now. I have three kids, and so did she. Your podcast makes Marie so human: anyone in Marie’s circumstances would have done as Marie did. I love this approach.

LikeLike