Last week we heard about how women in Rome used the no taxation without representation argument to get out of paying taxes. But this week we’re talk about how the same argument was used by American women to get themselves represented.

Because you might think it’s a clenching argument in the US, right? Super catchy phrase from the Revolution? All about how wicked and evil King George was towards the honest, hard-working folks from the colonies? When you’ve got a good marketing slogan, why change it?

And indeed the thought did cross the minds of some of the earliest suffragettes. Now bear in mind that women were not paying income tax at this point, because the federal income tax was only declared to be constitutional in 1913. So when people spoke about taxes in the 19th century, they usually meant state or local property taxes. And any woman who owned property, most assuredly owed property taxes, making her a taxpayer without representation.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote:

“Should not all women, living in States where woman has a right to hold property, refuse to pay taxes, so long as she is unrepresented in the government of that State? Such a movement, if simultaneous, would no doubt produce a great deal of confusion, litigation and suffering, on the part of woman; but shall we fear to suffer for the maintenance of the same glorious principles, for which our forefathers fought, and bled, and died? Shall we deny the faith of the old revolutionary heroes . . . by declaring in action, that taxation without representation is just? Ah! no; like the English Dissenters, and high-souled Quakers, of our own land, let us suffer our property to be seized and sold—but let us never pay another tax, until our existence as citizens, our civil and political rights, be fully recognized.”

Quoted by Juliana Tutt, “No Taxation Without Representation” in the American Woman Suffrage Movement, Stanford Law Review

Yeah, okay, so full points for drama and all that, but fiery speeches aside, the vast majority of women were not in fact prepared to let their property be seized and sold for the dream of a vote, and who can blame them? It’s not like there were a lot of other economic opportunities for women. That would be a seriously major sacrifice for a cause that often seemed doomed to failure anyway.

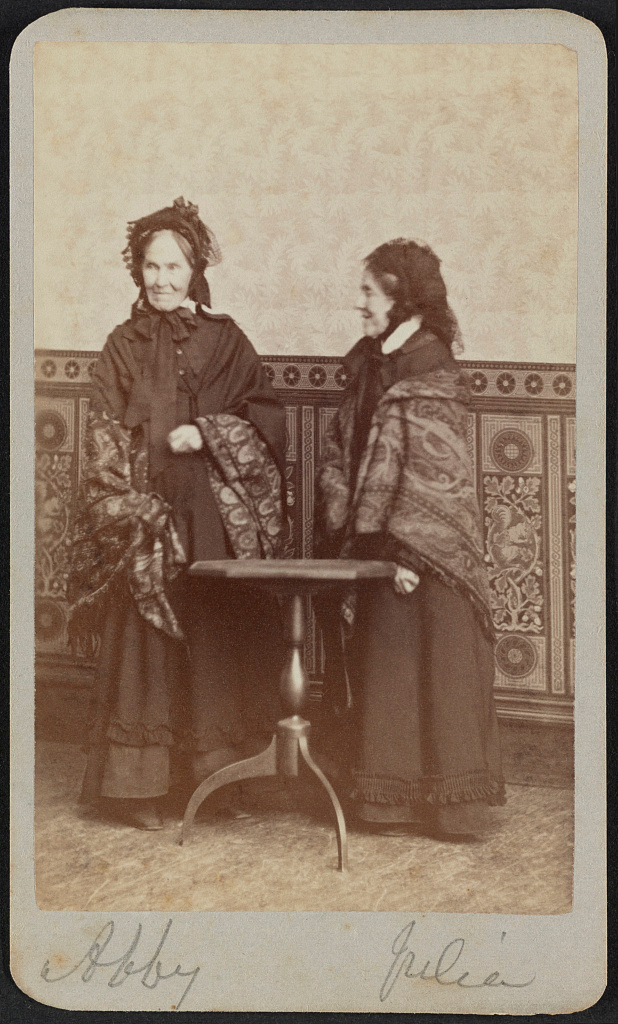

So this part of the suffragette plan never really took off in massive way, but it did take off in a few isolated cases. For example, Julia and Abby Smith were two sisters living in Glastonbury, Connecticut. They were educated (Julia published her own translation of the Bible). They had been involved in the abolitionist movement and later the women’s suffrage movement in a somewhat minor way. But their battle against the Glastonbury tax collector did not begin until they were ages 81 and 76, respectively. They owned Kimberley mansion, which just so happened to be the most expensive piece of real estate in town. In November 1873, the value of their property was assessed at $100 more valuable than previously. A quick survey of their neighbors revealed that two widows in town had also seen a rise in value (and hence a rise in taxes) but no property owned by a man had risen in value. I don’t know if the Smith sisters had been taught enough statistics to know that correlation is not causation, but you have to admit the circumstances were suspicious, and the Smith sisters did not restrain their highly educated rhetoric.

Said Abby:

“The motto of our government is ‘proclaim liberty to all the inhabitants of the land,’ and here, where liberty is so highly extolled and glorified by every man in it, one-half of the inhabitants are not put under her laws, but are ruled over by the other half, who can take all they possess. How is liberty pleased with such worship? [. . . .] All we ask of the town is not to rule over them as they rule over us, but to be on an equality with them.”

quoted by Molly May in The Smith Sisters

That is to say, no taxation without representation.

But the speech had no effect. So Julia and Abby put their heads together and decided they would not pay their property taxes. In response, the tax collector seized seven of their cows.

Newspapers took note. A defense fund was set up in their name, and indeed without even their knowledge or permission (May). They entertained reporters. Julia published a book.

But when you take a deeper dive, you realize that the Smith sisters had some advantages that many women simply didn’t have. Like the funds to buy their own cows back at auction. At a financial loss, I am sure, but they had the funds. Then their land was seized, which was a bigger hit. They won the subsequent lawsuit, but on a technicality, which didn’t much help the larger cause of suffrage (Tutt).

Julia and Abby Smith were two sisters who refused to pay their taxes without representation. You can read more about their story at Connecticut History.

The fact remained that many women wouldn’t or couldn’t take that route. The far more common approach to take was tax refusal, but tax protest, by which I mean that they paid their taxes, but attached a protest to it.

One clever poet published her protest in a book called A Book of Rhymes for Suffrage Times, which included this little gem, which I will point out, does not actually rhyme, but whatever. It goes like this:

Father, what is a Legislature?

A representative body elected by the people of the state.

Are women people?

No, my son, criminals, lunatics and women are not people.

Do legislators legislate for nothing?

Oh, no; they are paid a salary.

By whom?

By the people.

Are women people?

Of course, my son, just as much as men are.

Quoted by Juliana Tutt, “No Taxation Without Representation” in the American Woman Suffrage Movement, Stanford Law Review

Right, so women are people when it’s time to pay, but not so much when it’s time to vote.

So the no taxation without representation argument was out there, but it really wasn’t a linchpin in the general suffragette strategy and the reason for that it’s clever and catchy, but in fact it wasn’t all that good an argument. Here I am relying on Juliana Tutt in the Stanford Law Review for the logic of the argument and how it was used by both supporters of votes for women and its opponents.

The first premise is that taxes without representation is tyranny. The supporters had the founding father’s word on this, but people who were anti could counter that women were not the only group that were not represented. Minors and foreigners fell into the same camp and no one was claiming that they should be able to vote. And indeed the very founding fathers themselves obviously thought the argument had limits because they didn’t give the vote to women, or to slaves, or even to many white men, etc. Despite the fact that these people drank tea and used stamps and all the other products the King George and Parliament had been so eager to tax. So there’s that appeal to authority smashed.

Another premise was that large numbers of women were paying heavy taxes. Unfortunately, that argument was even more full of holes. As I said earlier, “taxes” usually meant property taxes, and most women didn’t own property, and therefore weren’t paying property tax. Now it’s hard to feel too glad about that. There’s a sexism problem there too, but the point remains: many of them weren’t paying property taxes. Sure, there were tariffs making the price of goods higher, but the whole point of tariffs was to make the tax invisible. People didn’t feel like they were being taxed. Ergo, we don’t need to give the vote to women because they aren’t being taxed.

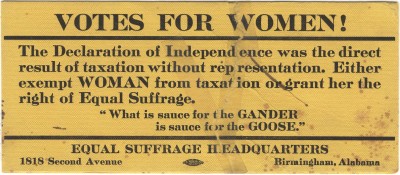

Some Alabama women made the direct connection to the Revolution, but this was not the most common argument in the woman’s suffrage movement.

Some jurisdictions (like Montana and Louisiana) did grant women taxpayers the right to vote on tax related questions and that was almost worse for the suffragettes, because they didn’t want piecemeal representation. They wanted universal representation for women, and the fact was that women were not universally taxed. So many suffragettes came out against the taxpayer suffrage, which suited the folks who didn’t want women voting just fine, as many of them were waxing on about how taxpayer suffrage was a slippery slope that would lead to universal women’s suffrage which would obviously be the beginning of total anarchy, destruction of western civilization and all that we hold dear, and so on (Tutt).

In 1913, the 16th Amendment and the United State Revenue Act brought us the federal income tax which Americans all know and love. Or something like that. Now this actually strengthened the suffragettes hand because vastly more women were taxed now that you didn’t have to own property. You only had to have a salary. Which still left out huge numbers of women, I might add, but it added a hefty amount to the list of taxpaying women.

And lo and behold only 7 years later, suffragists win and women get the vote. Note that I am not saying the income tax is responsible for that. There were a lot of other factors, but more women as taxpaying contributors did not hurt.

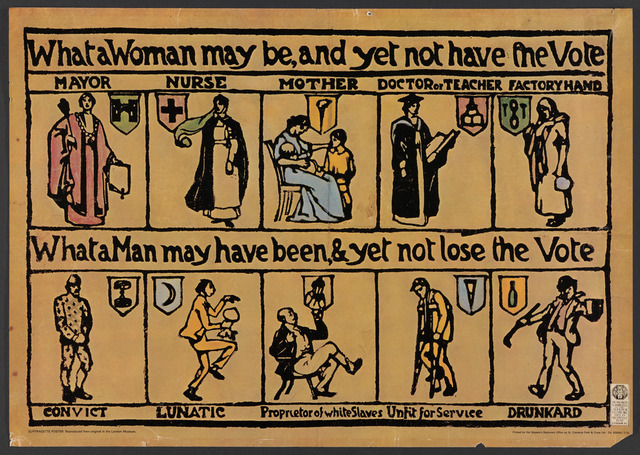

This clever poster forgot to mention “Taxpayer” as one of the things a woman could be without gaining the right to vote.

Image by The Suffrage Atelier, CC BY 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

You may think that having achieved the vote the argument is now done, but in that you would be wrong because there’s more. There is no point in having a right if you can’t exercise that right, and this is where we move into the poll tax.

Technically a poll tax has absolutely nothing to do with going to the polls. Etymologically, the word poll means head as in the hair on your head, and poll taxes are a truly ancient form of tax whereby the government says, “Do you have a head attached to your body? You do? Great. You owe taxes.” It’s also called a head tax or a capitation tax, which is the terminology used in the US constitution, but in modern English that just sounds much too much like decapitation, which is not what we mean at all.

Loads of people have instituted a poll taxes, everyone from Moses (Exodus 30:11-16) to Margaret Thatcher. (I have to say, I never expected to write a sentence with both those two people mentioned in it.) But anyway, poll taxes are very ancient, and when I was originally thinking about taxation and women that was what I was thinking of. Namely, were women included in poll taxes or not? Did our heads count? Or were they too substandard to count? That is actually still an open question for me because loads of sources, including modern ones say something like, “Everyone had to pay this tax” without specifying what they mean by everyone. Turns out that in the historical context for a lot of things “everyone” does not in fact include women, slaves, children, or foreigners. Except that sometimes it does. So I’m still turning that one over in my brain depending on the time and place in question.

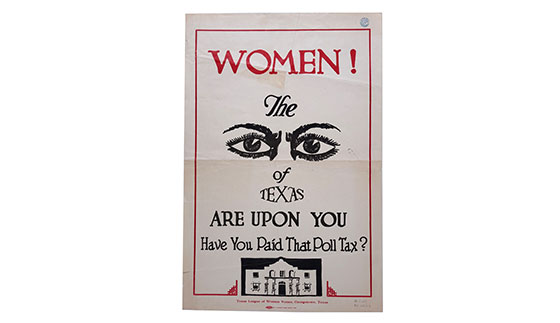

Even after suffrage was granted, some states required payment of a poll tax before voting. This poster reminded Texas women to pay it, but that didn’t help if you couldn’t afford it.

Image from The Story of Texas

But when I was trying to find out things like am I part of everyone or not, I was using Google and if you Google “poll tax” from within the United States, Google thinks you are talking about the taxes waged at the polls in the American south in the early 20th century. A worthy topic, but not quite what I was going for. Except that now it is what I am going for. Because you see, I knew about the American south poll taxes but I had learned about them in history class in the context of racism. The average black man was much poorer than the average white man and therefore couldn’t afford the tax and therefore couldn’t vote. So sorry. Too bad. Maybe next year. It’s disenfranchisement without legally disenfranchising anyone.

The racism angle is definitely true, and I do not in any way mean to minimize it. But guess who else turns out to be much poorer than the average white man? That’s right, your average woman, of any skin color.

The interesting thing about these Southern poll taxes was that if you stuck to the traditional definition of what a poll tax was, then you could claim that it wasn’t a voting fee. No, no, it was just a head tax, like many head taxes throughout history including in the North. It’s just purely coincidence that we never ask for proof of payment until you show up to vote. The amount was on the order of one or two dollars. If you are thinking, what’s one or two dollars between friends, you should be aware that it was cumulative. If you have not paid in past years you have to get completely up to date in order to vote. In 1936, one Nolen Breedlove owed the state of Georgia $13.50 in back poll taxes. It was the height of the Depression and had he chosen to spend his pennies elsewhere, that same $13.50 could have bought him 50 lbs of grits, 25 loaves of bread, 10 dozen eggs, 20 pounds of pork and beans, 10 pounds of lamb shoulder, 5 lbs of chuck roast, and 50 pounds each of potatoes, yams, and cabbages (Podolefsky, 845). Not a trivial thing when unemployment is high, wages are low, and you are living on the edge of subsistence.

Certainly there were wealthy women for whom this was not a big deal. But there were also single women, struggling to support themselves for whom it was a very big deal indeed. There were also married women. Bear in mind that a family would have to pay the poll tax twice in order to have both husband and wife vote. If you can only afford it once, the culture of the time pretty much guaranteed that it was the wife who would not vote. Even if you were a feminist woman, ahead of your time, eager to exercise your newly granted rights and earning your own income, you might run into difficulty. In Georgia, a wife’s salary was legally owned by her husband. If he disagreed, she could not pay her own poll tax, regardless of how wealthy the family was. It was a similar deal in Texas.

But not everywhere, South Carolina waved the poll tax for women on the slightly discouraging rationale that it would relieve husbands of the burden of paying for their wives to vote. I mean, yes. But at the same time, a resounding no. There’s still something wrong there. My source on this imagines a circumstance in which a South Carolina family might be too poor for the husband to vote, but the woman is free to vote, no charge applied, meaning we might actually get more women voting than men. But I would imagine the reason she’s just imagining this is that we have no actual incidence of this happening. It’s all theoretical.

Other subtle means were also tried. Alabama required that payment of poll taxes be made nine months prior to the actual election. Like anybody’s thinking of the election then! Men were reminded when paying property taxes that perhaps they might like to pay the poll tax too. But if you didn’t own property, like most women didn’t, no one would remind you. And by the time the election rolls around, it’s too late.

How much effect did this have? Well, one researcher found that in the 1940s Alabama voter lists included two men for every woman in most of the counties. In rural sections there might be as many as 3 or 4 men for every woman. This is not necessarily purely a matter of cost. It was often asserted that women were not interested in voting, and given current voter turnouts I think it’s true that many people, both men and women, are not interested in voting. However, the same study also found that sometimes a poor woman would say she wasn’t interested in voting because she was too ashamed to say that she simply couldn’t afford it (Podolefsky, 851).

And if you need further evidence, there is what happened when poll tax was abolished. Louisiana did it quite early (in 1934). The number of men voting rose by 25 percent, which is not trivial. The number of women voting rose by almost 100 percent (Podolefsky, 858).

But most poll taxes were still in place and women were very much involved in the fight to get rid of it. It was a piecemeal battle which I am not going to go into here. Suffice it to say that state after state repealed it and in 1964, the 24th Amendment was ratified and it said:

The right of citizens of the United States to vote in any primary or other election for President or Vice President, for electors for President or Vice President, or for Senator or Representative in Congress, shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State by reason of failure to pay any poll tax or other tax.

By then most states had gotten rid of it, but a handful had not, namely Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, Texas and Virginia, and the Amendment said nothing about what states could do with local elections. The Supreme Court ruled on that in 1966 and found poll taxes unlawful for any elections. That case was brought by one man and four women, all five of whom were African American.

Poll taxes were not finally declared to be illegal until the 1966 Supreme Court decision Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections. That case had combined several smaller cases together, but civil rights activits Evelyn Butts was one of the original plaintiffs.

Image from Wikimedia Commons

Of course, by 1966 the question was much less important that it had been. The amount of the tax was coded into law, so it had not risen at the same rate as inflation. One or two dollars was nowhere near the monumentally prohibitive amount it had been when Nolen Breedlove had protested. So reduced burden and all that is good. Unfortunately, it was also true that other means of disfranchising voters had been tried and tested by then, some of which are far more difficult to prevent than the poll tax.

So there you have the full circle. Hortensia used no taxation without representation to mean she didn’t want to pay taxes. The early American suffragettes used to say they did want representation along with the tax burden. And later women’s rights advocates used it to say they wanted representation free and clear of any particular tax burden.

My question is: if you had the option of foregoing your representation in exchange for a tax exemption, would you take it?

Sources and Images

I had three major sources for this episode:

- May, Molly. “The Smith Sisters, Their Cows, and Women’s Rights in Glastonbury – Connecticut History | a CTHumanities Project.” Connecticut History | a CTHumanities Project – Stories about the People, Traditions, Innovations, and Events That Make up Connecticut’s Rich History., 12 Mar. 2021, connecticuthistory.org/the-smith-sisters-their-cows-and-womens-rights-in-glastonbury/. Accessed 25 Feb. 2024.

- Ronnie L. Podolefsky, “Illusion of Suffrage: Female Voting Rights and the Women’s Poll Tax Repeal Movement after the Nineteenth Amendment”, 73 Notre Dame L. Rev. 839 (1998). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr/vol73/iss3/16

- Juliana Tutt, “No Taxation Without Representation” in the American Woman Suffrage Movement, Stanford Law Review, Volume 62, Issue 5, Page 1473. Available at http://www.stanfordlawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2010/05/Tutt.pdf

Feature Image from Wikimedia Commons

You make history SO interesting! Thank you for sharing your research.

LikeLike

[…] Most Blacks did not. Their grandfathers were still enslaved during the war. Also, there were poll taxes, which hit all female voters quite hard, but there’s no doubt that they hit female voters of color hardest of all. These and other more […]

LikeLike