Note on Images: Many of Georgia’s works are still under copyright. I believe the use of them here is considered fair use because they are readily available on the internet (see lots of links below near each image), because this site is free and purely informational, and because it does not reduce the commercial value for the copyright holders. If that is not the case, please contact me and I will remove the images.

If you are familiar with Georgia’s work, it may come as a surprise that she was not born in the American Southwest. Nope, she’s a Midwest girl, born on a Wisconsin farm in 1887. She attended a one-room schoolhouse and didn’t get any art training until age 11, when it was firmly decided that her sister Ida was the talented one (Rubin, 112). Fortunately, Georgia didn’t care too much what other people thought, so she ignored that assessment. In 8th grade, she decided to become an artist when she grew up.

Up until this point, Georgia had spent her life in one small community, but all that was about to change. She spent a year at a convent boarding school, and then a year at the public high school, and then her family moved from Wisconsin to Williamsburg, Virginia. The reason was that her father’s family were rapidly succumbing to tuberculosis, and they thought a milder climate might save him. If you know anything about TB, that will strike you as odd because Virginia’s climate was worse for TB, but the O’Keeffe’s didn’t know that (Robinson, 38). The girls at school didn’t like Georgia’s accent or her clothes (Robinson 39-42).

After a little of that, though, Georgia was old enough to escape. She soon headed to the Art Institute of Chicago, where she advanced quickly, only to fall sick with typhoid fever, which forced her return to Virginia. A year later she enrolled in art school in New York. The New York art scene was currently dominated by Alfred Stieglitz, a photographer who also owned a studio called 291. It was Stieglitz who first imported Rodin’s work from Paris, to be displayed in the United States for the very first time. Georgia, a lowly student, went to see it, and she didn’t like it (Rubin, 28). And she had no chance to learn the error of her ways because her parents were in financial difficulties. They couldn’t afford to keep her in New York.

Georgia went back to Chicago to earn her keep as an illustrator, which she didn’t like. That wasn’t real art, blah blah blah, and she got the measles. On her recovery, the financial situation was no better, and she got a job teaching art.

She also enrolled at the University of Virginia where her own art teacher opened the world of abstraction to her. It was about shape and color and negative space. It meant art could be a thing entirely her own. If you’ve been keeping track, Georgia has been in an entirely new social environment every year for about a decade, and she wasn’t done because a friend sent word that a school in Amarillo, Texas, was looking for an art teacher.

Now I have driven through Amarillo many times, and it is primarily memorable for the ads that promise you if you can eat a 72 oz steak in one sitting, you can have it for free. In 1912, Amarillo was a howling wilderness, at least in comparison to New York or Chicago. It takes a special kind of young single female to be excited about going there alone.

Georgia was that kind of special. She was thrilled. Her mother had read her stories of Billy the Kid and Kit Carson when she was little, and now she was going out their way herself! Georgia loved Amarillo, the openness, the sky, the people. Okay, not the school administration people, it was hard to love them, she had a few run-ins actually, but all-in-all, she wasn’t hankering for the east.

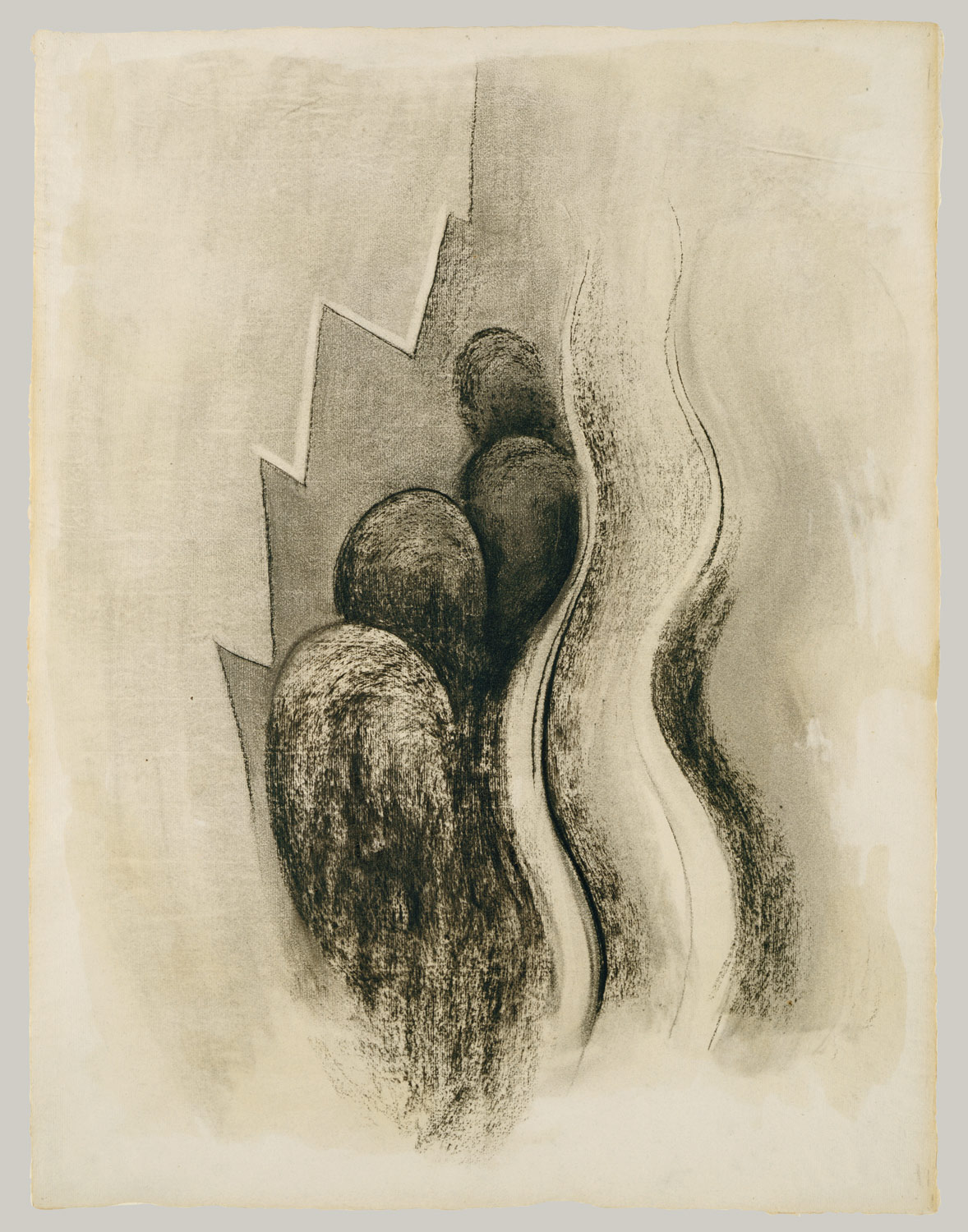

On the other hand, settling down wasn’t really a concept she knew about, and by 1914 she was back in New York, studying and visiting Stieglitz’s art gallery with her friend Anita, and then she was gone again, teaching, but also drawing in black and white only, all of it abstract with clarity and intention about lines and shapes and tonal values. She mailed these drawings to Anita for her opinion with strict instructions not to share them with anyone else.

Sometimes our friends know better than we do because Anita disobeyed. She took them personally down to Alfred Stieglitz, who had exhibited the likes of Rodin and Picasso, and “he looked… he looked again… the room was quiet. Then he smiled and said, “You say a woman did these? Well, tell her they’re the purest, finest, sincerest things that have entered [my studio] in a long while… I think I will give these drawings a show. Finally, a woman on paper!” (Rubin, 42).

Just like that Georgia had found her champion, which is really what every creator needs. But there were still bumps in the road. Stieglitz had said that he would give her an exhibition, but he did so without discussing or even informing her of dates and terms, which was super annoying. Georgia was actually back in New York and a classmate said Stieglitz had an exhibit on from someone named Virginia O’Keeffe. Furious, Georgia stormed down to the gallery and insisted that he take them down. It was the first, but not the last time they met. The first but not the last time Georgia was on the receiving end of the trademark Stieglitz charm, assurance, glamour, and flattery. The exhibit stayed up.

Georgia went back to Texas to teach (a different post, not the Amarillo one, we couldn’t be that repetitive), but in her time off she painted and wrote letters to Alfred Stieglitz (Rubin, 48). Another event of note at this time, she accidentally visited Santa Fe, New Mexico, because her trip to Colorado was diverted there en route. It was the first time she had been to New Mexico, and she found it even better than Texas. To which I can say: Yes, yes, it is. The fact that I’m from New Mexico is not in anyway relevant to that entirely unbiased sober assessment. Georgia later said:

“When I got to New Mexico that was mine. As soon as I saw it that was my country. I’d never seen anything like it before, but it fitted to me exactly. It’s something in the air, it’s different. The sky is different, the wind is different.”

(quoted in Barbara Buhler Lynes in Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Collections, p. 222)

However, Georgia’s visit was brief. Alfred wanted her to come back to New York, and when she did, he visited her daily. They were in love. Which presented all kinds of obstacles. For starters, he was 54. She was 30. Also her career was dependent on Alfred’s favor as the most powerful man in the New York art world, so that’s a sketchy basis for an equal relationship. And then there was the fact that Alfred was married. Because of course he was.

None of that stopped their intense relationship. Stieglitz photographed Georgia over 300 times, some of them nude and he exhibited them, which also muddied the waters. Was she an artist? Or only a model? A colleague? Or a love interest? They didn’t care. They were happy.

Georgia painted her joy in Music, Pink and Blue.

Available online here and here and here and here

In the Whitney Museum of American Art

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

Alfred asked her what she wanted most, and she said a year to paint with no need to teach. Alfred rustled up a patron to provide just that.

They did not get married because Alfred was still struggling to get a divorce, which took years. They did not have a child because Alfred didn’t want one. He was already not doing well at being a father to his current child. Also he told Georgia that she’d never be able to paint if she had a child around. Not an uncommon attitude at the time, but still it grates, how many women were told that had to choose either a family or a career because having both was only an option for men. Anyway, it was a grief to Georgia, but she gave in.

Alfred continued to give her shows, all of them crowded and well-reviewed. Especially when you consider that she was not a man and she had never trained in Europe, both of which things were still basically required for a serious artist.

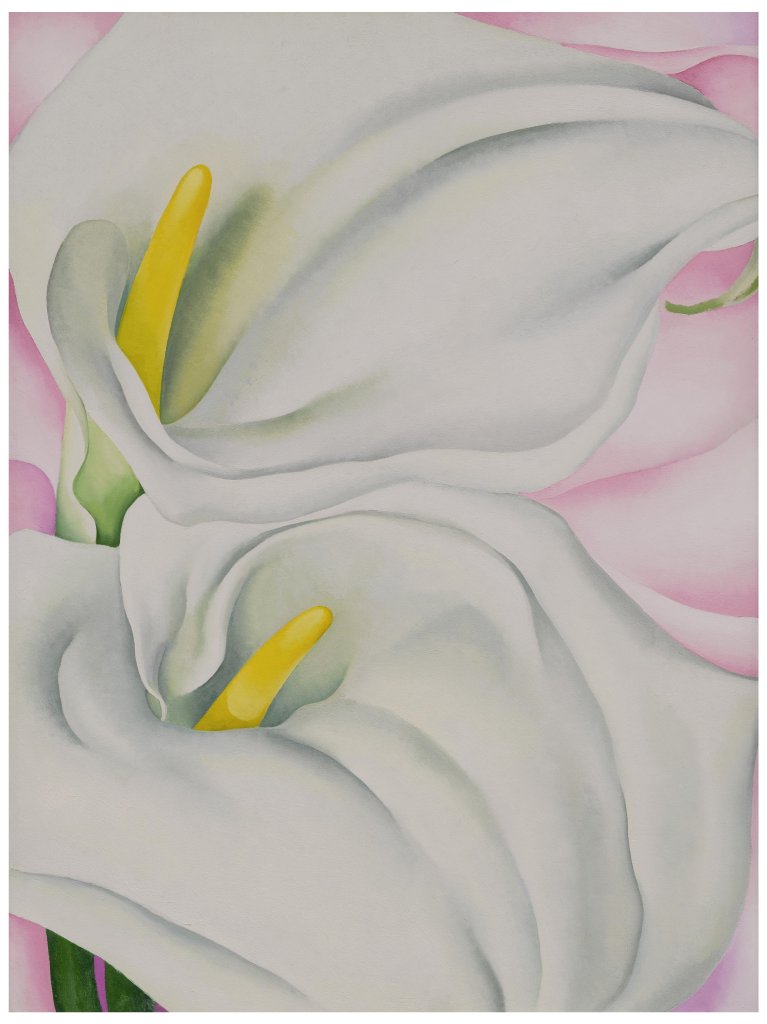

1924 was a watershed year. It was the year Alfred’s divorce finally became final, the year he and Georgia married, and it was also the year she painted her first gigantic flower. Some of them are large in the sense that the canvas itself is large. But most are large in the sense that they are zoomed in, so that what was a small flower takes the entire canvas, maybe even spilling off the canvas. For her it was all about perspective. “That was in the 20s,” she said later, “and everything was going so fast. Nobody had time to reflect . . . Well, [a] flower was perfectly beautiful. It was exquisite, but it was so small you really could not appreciate it for itself. So then and there I decided to paint that flower in all its beauty. If I could paint that flower in a huge scale, then you could not ignore its beauty” (quoted in Robinson, 278). And also “When you take a flower in your hand and really look at it, it’s your world for the moment” (Robinson, 33).

Reviewer after reviewer loved her flower paintings. They were wonderful! Such an explicit and open celebration of feminine sexuality in all those vulval shapes and forms! Aren’t we sexually free now! Isn’t it great!

Georgia was both surprised and offended (Robinson, 282). To be sure there are similarities between the shape of a flower and female genitalia, but that’s biology’s fault, not Georgia’s. That was not what she had in mind when she painted them.

By now Georgia was earning her own living as a painter. Alfred was her agent, and he was a peculiar one. He had the basic idea that the public should buy art and support artists. And he simultaneously had the contradictory idea that the exchange of money was sordid and demeaning, and art should be shown only to those who were worthy enough to truly appreciate it. He often did not want to actually sell anything, which is not exactly the attitude you expect an agent to take.

In 1927 an anonymous American living in France wanted to buy six calla lily paintings of Georgia’s. Alfred wanted none of that. How could he judge worthiness if it was anonymous? Rather than say no, Alfred named an outrageous price of $25,000. Anonymous said sure. Alfred blinked. And then he added a whole bunch more demands, like the buyer had to display it in his or her own home and never ever resell. Anonymous said okay. The paintings were handed over, and it was front page news that Georgia’s work was enormously valuable (Rubin, 78; Robinson, 305). Somehow, the very fact that her work was so hard to buy drove up demand and the prices.

So Georgia had made it big in the art world, in a way that few of the women in this podcast series ever did. But on a personal level she was actually floundering.

There were many differences between her and Alfred. She loved to travel. He never wanted to go anywhere but his lake house in the summer and the city the rest of the year. She craved quiet and solitude. He wanted an endless stream of company. She liked simplicity. He worried about everything. All of that might have been worked through, but she had discovered something else. Something more disturbing.

Alfred was a man who had humiliated his first wife by having a very public affair with a younger, more beautiful woman, and he was still the same man, now humiliating his second wife by having a very public affair with a younger more beautiful woman. Surprise, surprise. Someone might have seen that coming, but Georgia didn’t.

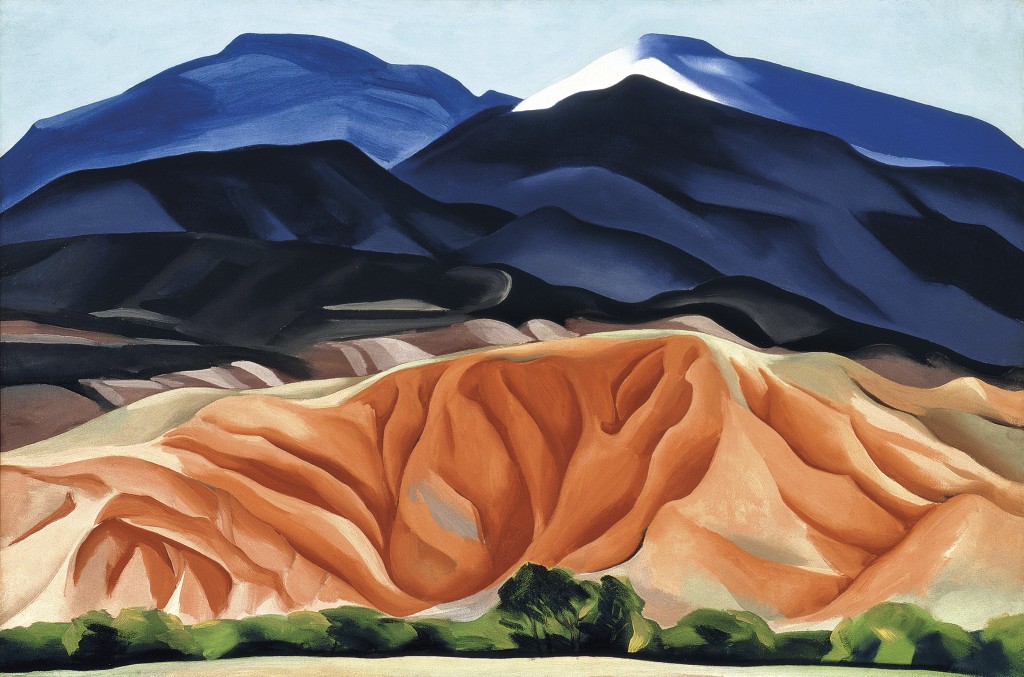

Alfred learned nothing from his previous experience. He still naively hoped that his wife wouldn’t mind. He was just as wrong as before. As the adoring Dorothy Newman inserted herself into their personal life and their friend circle and the running of the studio, Georgia decided to go to New Mexico. Not permanently. Just for some space, which is something New Mexico has a lot of.

Alfred was invited, but he hated travel, remember? So she went with a friend, and it was as lovely as the first time. Wide open vistas and such color! Color was Georgia’s very favorite thing. Alfred’s lake house in upstate New York was an endless palette of green, but here she said “all the earth colors of the painter’s palette are out there in the many miles of bad lands. The light Naples yellow through the ochres—orange and red and purple earth—even the soft earth greens” (quoted in Lynes, 230).

She learned to drive so she could explore on her own. She went camping so she could paint in the dawn’s first light. She continued to experiment with perspective, like when she lay down on her back and painted a ponderosa pine tree, looking straight up.

She also wrote to Alfred daily. He was worried she would never come back, but she did come back. Her New Mexico paintings were exhibited to rave reviews (Rubin, 86). She went back again the following summer. She was particularly interested in the stripped and bleached bones she could find on the desert. They had such beautiful shapes. She painted them again and again.

Reviewer and reviewer loved her bone pictures. They were wonderful! Such an explicit and open salutation of death and mortality in all those skulls and pelvises! Aren’t we free about our Freudian impulses now! Isn’t it great!

Again, Georgia was surprised and offended. She chose the bones for their shape, not their metaphorical significance. Remember she had trained as an abstract artist: color, form, feeling were important. What the physical object actually was, wasn’t (Robinson, 368).

Of course, it is possible to speculate about the subconscious motives. She was striking out in an unexpected way, establishing her independence as an artist. She was establishing her independence in the business sense too. She accepted a mural commission in New York. Alfred was furious. He was her agent, and he hadn’t been consulted, nor were they paying her enough. In his mind, this was betrayal. Professional betrayal. What they did not discuss was that there was an ongoing personal betrayal with Dorothy Newman, and it was on his side. (Robinson, 371).

The mural project collapsed anyway. Georgia walked off the job because the plaster was still wet when they told her to paint on it. Alfred was delighted. Georgia was crushed. I mean truly crushed. Her reaction was physical: short breath, chest pain, difficulty speaking, blinding headaches, fatigue, weeping, hypersensitivity to noise, water, and crowds.

She was admitted to a hospital for psychoneurosis (Robinson, 385). It took months for her to recover and she could not paint. It is difficult enough to diagnose mental illness in the present, much less the past. But it is hard to avoid the speculation that Georgia, who had experienced a truly astonishing amount of personal success, was having a hard time coping with failure. She had evidently failed as a wife, since her husband was looking elsewhere. And if that was gone, she had only her art to form her identity, her self-image. And now she had failed to complete a commission. The only commission she had ever negotiated for herself.

It is possible and indeed quite rational to argue against both those definitions of failure, but mental illness is not rational. For his part, Alfred felt racked with guilt and anxiety. As well he should, I might add. His romance diminished, though Dorothy Newman would stay around, involved in the studio and the friend circle for the rest of his life.

Eventually, Georgia came over and through and out the other side of her pain. She chose to stay married, even to stay affectionate, but the rapturous love was over. Alfred was aging and he needed her. She took care of him. He acted as her agent. But she stopped conforming to all his neediness. When he hosted parties, she participated only if she felt like it. When she wanted a larger apartment in New York and he was fretting, she told him she was going, would he like his things moved too? He went (Robinson 413).

She was making her own choices now, and she felt no need to explain them. In fact, when a friend was having marital trouble, this was the advice she wrote:

“Try not to take it too seriously—or maybe I mean take it more seriously—imagine it is two years from now—and in the meantime don’t do anything foolish. Only time will make you feel better—and don’t talk about it to people if you don’t want to. . . Why should you be expected to explain your personal life to anyone—it is rather difficult to even explain to oneself. . . don’t look ahead or behind and maybe you can enjoy the “now” and not feel a bit disturbed . . . And don’t worry about what you are going to do with your life—you can manage.”

quoted by Roxana Robinson, in Georgia O’Keeffe: A Life, p. 393

Georgia still came to the city every winter. She went to the lake house every spring to open the house for Alfred. But every summer she went to New Mexico without him. She bought two houses there, both of them far from people. Also far from services. Georgia was giving up trivialities like electricity and running water. Such things were certainly available in New Mexico, but she didn’t choose any houses like that. Her house in the small community of Abiquiu was a total ruin when she bought it. She paid $10 for it, which was a great deal for the previous owner, who had paid only $1 for it, a ten-fold return on investment for them (Robinson, 449).

Georgia slowly began fixing it up. Her landscapes peak during this period, and they are gorgeous swirls of earthy colors. Dreamy is one word that has been used to describe them. She has smoothed out the hard edges of reality, looking as usual, at the color and form rather than the fine detail. The red rock of New Mexico never ceased to thrill her.

In 1946, Alfred died in New York. Georgia barely got there in time. She knew that he was sickening, but when was he not fretting for her to come back? So she didn’t hurry. When she did get to the hospital for the final hours, she was sharing them with Dorothy Newman (Robinson, 464).

Alfred’s will left Georgia as his primary heir and sole executor. Her first act was to kick Dorothy out of the studio permanently (Robinson, 464). That done, she spent three years settling 850 works of art, arranging two shows: one of Alfred’s own art, and one of his collection. She didn’t believe in hoarding material possessions, and her dispositions were mostly gifts to museums. The National Gallery in DC, the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, and a host of other institutions benefitted. The personal papers (of which there were a great many) went to the Beinecke library at Yale with strict instructions that the letters would not be read for thirty years (Robinson, 470).

After all was done, Georgia moved permanently to New Mexico. As isolated as New Mexico may seem to a New Yorker, she was not really alone there. It did have its own community. Abiquiu’s people were Hispanic, Catholic, and family oriented. Georgia was an Anglo, Protestant, single woman living in a ruin. She didn’t exactly blend in.

What she did have was great respect for the land, its people, and their religion. She hired people from the town to help with her renovations and to attend to her house. She attended both Catholic and indigenous religious rituals and admired the power and dedication she saw there. She funded a community gym and a clean drinking water pipeline. She encouraged local youth to attend college and financially contributed to make it happen (Robinson, 486-488). To their surprise, many in Abiquiu decided they liked her after all.

Georgia continued to paint. In particular, her patio door fascinated her as a subject. She also continued to travel, and she painted cloudscapes that she saw from the plane.

By the end of the 50s, an amazing thing had happened. Georgia had lived and painted long enough to go out of style and then come back into style. Not many people manage that. Interest in her soared. A stream of acolytes and journalists began showing up at her door and she was not at all pleased. She had always valued privacy. She become more and more withdrawn and crusty, even downright rude. Friends who had supported her for years began to fall like bowling pins. Anita Pollitzer, who had initially shown her work to Alfred, kicking off her career? She spent ten years on a biography of Georgia only to have Georgia say she pretty much hated it, which pretty much ended their friendship. Devoted housekeepers were let go because they failed to live up to her increasingly difficult expectations.

The person who rose to fill the void was one Juan Hamilton, or John Hamilton, if you prefer. She had initially hired him to do odd jobs around the house. But he was charming and easy to talk to, and soon he was far more than a hired hand. He was around all the time, managing her affairs, both artistic and otherwise, edging out her agent, her extended family, everyone. Some people found this arrangement distinctly troubling.

She died in 1986 at the age of 98. After a legal kerfuffle involving questions on just how much she really intended to leave to Juan Hamilton, the majority of her estate was given to museums and charities.

Georgia is to this day among the most critically acclaimed American artists of any gender. And though money may be sordid and demeaning, she also holds the record for the highest auction price ever paid for a female artist’s work. I hope you agree that she is a fitting end to a series that began with unnamed, unpaid ancient women painting on rocks.

Selected Sources

Lynes, Barbara Buhler. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Collections. New York, Abrams, 2007.

O’Keeffe, Georgia, et al. My Faraway One. Volume I, 1915-1933 : Selected Letters of Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz. New Haven, Conn., Yale University Press, 2011.

Robinson, Roxana. Georgia O’Keeffe: A Life. Harper Perennial, 1989.

Susan Goldman Rubin, and Georgia O’keeffe. Wideness and Wonder : The Life and Art of Georgia O’Keeffe. San Francisco, Chronicle Books, 2010.

The feature image is Oriental Poppies by Georgia O’Keeffe, Fair use, Wikipedia, also available here.

I have never seen The Lawrence Tree before, and I have never before liked Georgia’s work. Now I want a print. Thanks again, Lori!

PS– the relationship with Alfred was fascinating.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m so glad! I’ve always liked Georgia’s work, but I had seen a lot less of it than I thought before I started researching.

LikeLike

[…] 10.14 Georgia O’Keeffe, an American Painter at Her Half of History […]

LikeLike

[…] 10.14 Georgia O’Keeffe, an American Painter at Her Half of History […]

LikeLike

[…] 10.14 Georgia O’Keeffe, an American Painter at Her Half of History […]

LikeLike

[…] 10.14 Georgia O’Keeffe, an American Painter at Her Half of History […]

LikeLike

[…] 10.14 Georgia O’Keeffe, an American Painter at Her Half of History […]

LikeLike

[…] 10.14 Georgia O’Keeffe, an American Painter at Her Half of History […]

LikeLike

[…] 10.14 Georgia O’Keeffe, an American Painter at Her Half of History […]

LikeLike

[…] 10.14 Georgia O’Keeffe, an American Painter at Her Half of History […]

LikeLike

[…] 10.14 Georgia O’Keeffe, an American Painter at Her Half of History […]

LikeLike

[…] 10.14 Georgia O’Keeffe, an American Painter at Her Half of History […]

LikeLike

[…] 10.14 Georgia O’Keeffe, an American Painter at Her Half of History […]

LikeLike

[…] 10.14 Georgia O’Keeffe, an American Painter at Her Half of History […]

LikeLike

[…] 10.14 Georgia O’Keeffe, an American Painter at Her Half of History […]

LikeLike

[…] 10.14 Georgia O’Keeffe, an American Painter at Her Half of History […]

LikeLike

[…] 10.14 Georgia O’Keeffe, an American Painter at Her Half of History […]

LikeLike