Take a quick glance down at whatever you’re wearing at the moment. I don’t know whether you are in pajamas or an evening gown, but whatever it is, it’s cheap. Dirt cheap by historical standards. In the pre-Industrial world, cloth of any kind was valuable and priced accordingly because it takes an unbelievable number of hours to get from a cotton plant or a silk worm or a sheep to anything wearable, even if you’ve got low standards.

The Industrial Revolution brought us cheap cloth, and it is difficult to overstate the impact. The British empire was built on cheap cloth. The economy of the world was completely rewritten in favor of those who had the textile mills.

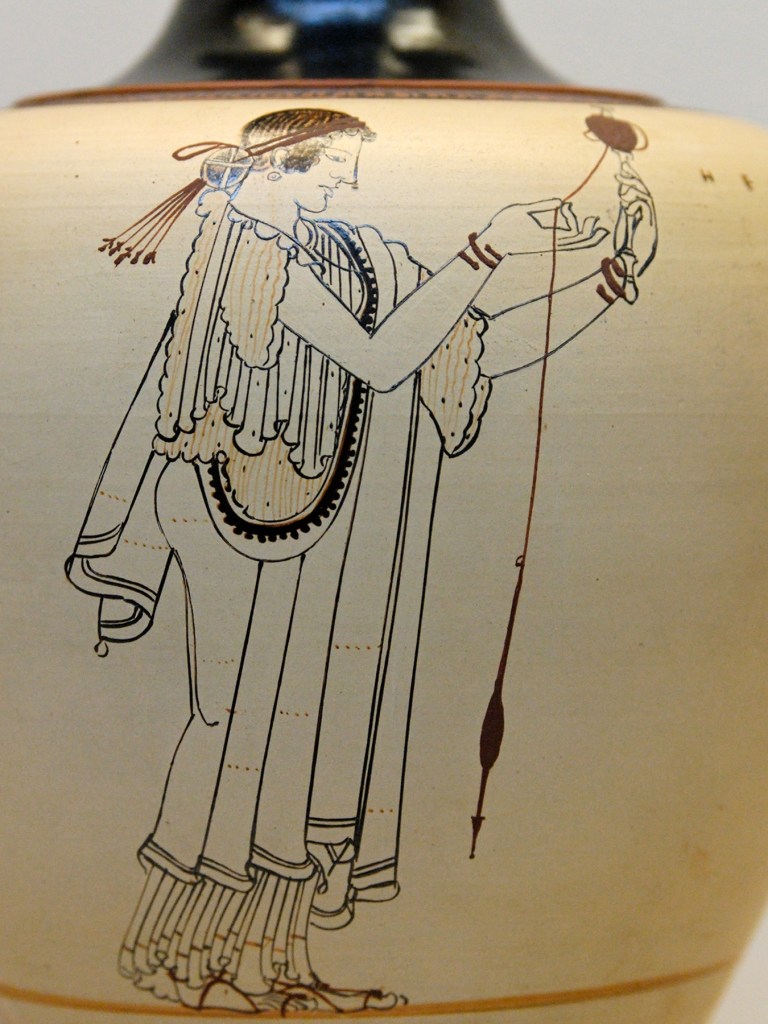

On a more podcast-specific note, the Industrial Revolution changed the lives of women in particular. For millennia, the primary responsibility of the female half of humanity was to spin (and then later to weave and sew, but really, to spin). It crosses cultures and ages and class distinctions. Practically the only thing that everyone has always agreed girls should be taught is how to work with thread. If you are female and you do not know how to spin thread, you are, historically speaking, hopelessly uneducated. I place myself firmly in that category.

As I mentioned last week, the early factory jobs were viewed as great all the way around. The kids would learn the value of hard work, the parents would get a steady paycheck, and society would gain the stability of not having a lot of useless parasites draining the resources. Everybody wins!

The Early Textile Mills

It was only natural to say that girls who used to be at home spinning thread could now work in the textile factories. Boys too (the factories weren’t discriminatory), but a lot of girls were hired. In the early days, mill owners could claim that factory work was easy. And in some senses that was true. It was so easy a small child could do it. The most common job for a girl in a cotton mill was that of spinner. A spinner’s job was to walk up and down the rows of machinery, brushing lint off the machines and looking for breaks in the thread. If she saw a break, she was to tie up the ends. That’s it. That’s the whole job (Trattner, 81). Compared to life on a farm, with its back breaking labor, a spinner’s job looked restful, especially if you hadn’t actually tried it yourself.

George Washington certainly had no complaints when he visited one on Wednesday, October 28th, 1789. He wrote in his diary:

They have 28 looms at work, and 14 Girls spinning with Both hands, (the flax being fastened to their waste.) Children (girls) turn the wheels for them, and with this assistance each spinner can turn out 14 lbs. of Thread pr. day when they stick to it, but as they are pd. by the piece, or work they do, there is no other restraint upon them but to come at 8 o’clock in the morning, and return at 6 in the evening. They are the daughters of decayed families, and are girls of Character. None others are admitted… This is a work of public utility and private advantage.

George Washington (Diary on Wednesday, October 28th, 1789)

That particular mill was operated by horse power because no one outside the British Isles yet knew any other way to do it. The British were keen to keep the knowledge of their technological breakthroughs right there at home. If you understood the inner workings of the machines, you could not leave the country.

Of course, it didn’t work. One child apprentice named Samuel Slater was later to be called Slater the Traitor because he slipped away to America where the knowledge in his head was a hot commodity. In 1790 his first mill opened, and his first employees were local children between the ages of seven and twelve years old. (Tucker, ‘The Merchant’, 299). France, Germany, Belgium, and many other countries were not far behind.

Only it turned out that mill work was not as easy as everyone had claimed. I mean, sure, the actual job could be done by unskilled children, but it came with some hazards that people fresh from the farm had never considered.

For starters, the machines were so loud that no talking could be heard. To communicate at all you had to shout. All day.

Opening windows allowed the fresh air with all its varying humidity levels in. Varying humidity led to more breaks in the thread. Therefore many owners wanted the windows closed. Therefore no air circulation. Therefore, workers were constantly breathing lint. This had no immediate bad effect, so owners were able to say it wasn’t a problem. But spinners developed dry coughs which gradually grew more severe until they were spitting blood and eventually dying. A cotton mill girl had less than half as much chance to reach adulthood as her counterpart girl outside the mill (Trattner, 81).

Respiratory diseases killed you slowly. The quicker way to die was on the machines themselves. Spinners were often too small to reach the threads that had broken. Therefore they had to climb up on boxes or the machinery itself. One slip and you’d get crushed in the whirling metal. Even if you didn’t die, you might well lose a finger or another expendable body part (Trattner, 81).

Then there was the schedule. Agricultural work was hard, but at least a farm had natural rhythms. There were times of day and seasons of the year where the work eased, and you could rest a little. Machines didn’t care about any of that. They pounded on, twenty-four hours a day, which meant that many young children were assigned to the night shift: twelve hours on their feet in that environment, six days a week (Trattner, 81). Washington may have seen girls with an 8 to 6 schedule, but loads of other girls were soon working much longer than that. You can forget going to school afterwards. When would you have the time or the energy?

Early Legislation on Child Labor

In 1802, Britain passed its first piece of legislation on child labor. It said no night shifts for anyone under 21, and no shifts longer than twelve hours, and a basic education was required. I think you’ll agree that’s not excessively progressive, but the law had absolutely no means of enforcement, so effectively, it did nothing. In 1819, a second try said no one under the lofty age of nine could be employed at all, but again, no enforcement (Parliament). Child education and child labor laws went hand-in-hand because if a child had to be at school, then she couldn’t be at work and vice versa. Other countries were behind Britain in passing legislation, but then again, they were behind in building the mills too, and they did get there eventually.

The Prussian effort was initially sparked by King Frederick William III, who was alarmed by reports that factory labor led to health problems (in boys) which led to soldiers unfit for military service, and obviously we can’t have that. Nevertheless, the initial attempts at regulation failed because the chief proponent framed it as a way to “cultivate the moral, intellectual, and physical capacities of the working classes.” That was not a goal the Prussian elites thought worthy of their support. The subsequent attempts stressed that education was important to prevent an “overpopulation of crude individuals… likely to avenge themselves and turn violent uprisings against those who abused them irresponsibly in their youth” (Anderson).

Now that was a goal that every European elite had understood since the French Revolution. Self-preservation was something they could get behind. The law passed, and Prussia got a minimum working age of nine years. In France it was eight. In Belgium, the law didn’t even pass. These laws also set rules about working hours and safety inspections, but I’m not sure any actual children noticed the difference (Andersen).

Writers and Public Opinion

The nineteenth century pressed on, and nonpoliticians began expressing their disapproval. In 1838, Charles Dickens wrote Oliver Twist which drew attention to child labor. He himself had spent two years of his childhood in a workhouse while his family were in debtor’s prison. In 1843, Elizabeth Barrett Browning wrote a poem called “The Cry of the Children:”

Do ye hear the children weeping, O my brothers,

Ere the sorrow comes with years ?

They are leaning their young heads against their mothers, —

And that cannot stop their tears.

…

"For oh," say the children, "we are weary,

And we cannot run or leap —

If we cared for any meadows, it were merely

To drop down in them and sleep.

…

For, all day, we drag our burden tiring,

Through the coal-dark, underground —

Or, all day, we drive the wheels of iron

In the factories, round and round.

…

And all day, the iron wheels are droning ;

And sometimes we could pray,

'O ye wheels,' (breaking out in a mad moaning)

'Stop! be silent for to-day ! '

But all this hand wringing had very little effect. In part because the loudest cries were not coming from the people with the most right to complain: namely the kids themselves or their parents.

Objections to Reform

In the American South, for example, where my own ancestors worked in the cotton mills, mill workers usually came from Appalachian and Piedmont farms that were by this point so over farmed and under-fertilized that they didn’t really produce much. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, these people flocked to the mill towns because in a choice between hard labor and starvation, most people choose hard labor. They were not mourning missed educational opportunities because they’d never had those before either (Trattner, 38). Children expected to work for the family, so mill work was not a surprise.

Plus, a lot of the people saying this was all morally wrong were Northerners. And there was nothing better calculated to put a Southerner into an intractable position of indignant stubbornness than a Northerner waxing on with moral superiority (Trattner, 40).

Race got dragged into it too because of course it did. Southern mill owners did not hire black children, which is a whole issue in and of itself. Black girls were still picking cotton or working as maids. Mill owners could claim they were helping white children because life in the mill was better than life on the farm, and the mill workers largely agreed. It’s always nice to know that no matter how bad things get, you still have someone else to look down on. At the same time those concerned about both child welfare and white supremacy complained that here we had white children working themselves to an early uneducated grave, while black children were going to school and doing wholesome farm labor in the fresh air. The black children were going to get ahead! (Trattner, 85-86).

All this leaves me confused about whether life in the mill was better or worse than life on a farm, but I think the answer is: it depends on the farm. Either way, the racism is clear.

Actually, the racism is still another layer deep. It’s not like Northerners didn’t have child labor. They did. It’s just that Northern child labor largely involved immigrant children, many from Eastern Europe. The child labor problem, according to some, was that the South was using native-born Anglo-Saxon children. One Southerner went so far as to encourage massive immigration to the South. Because putting immigrant children in the mills was perfectly all right, according to him (Trattner, 86).

So far, we have talked almost exclusively about mill girls because that was the earliest and most visible form of industrialized labor, but by the early 20th century, the idea had vastly expanded. well beyond cotton mills.

Photographers and Public Opinion

Americans who bought industrially-made products were able to enjoy them with child labor safely out of sight, out of mind, until a photographer named Lewis Hines took a job with the National Child Labor Committee. They say a picture is worth a thousand words, which is too bad for me since I’m really far more comfortable with words.

Hines’s job was to bring a sad reality home to middle-class Americans, and he did. So much so that employers actively hid the children from him. Over a decade, Hines posed as a fire inspector, an insurance salesman, and an industrial photographer here to photograph the machinery (though if you don’t mind, I need to give a sense of scale, so if that worker there could just stand next to the machine, thanks so much, that’s very helpful) (Freedman, 26).

For example Hines took a picture of Addie Card, thin and barefoot, leaning on a machine full of bobbins of thread.

Or there’s Gertrude Belier, sitting at a sewing machine in a room full of girls and sewing machines.

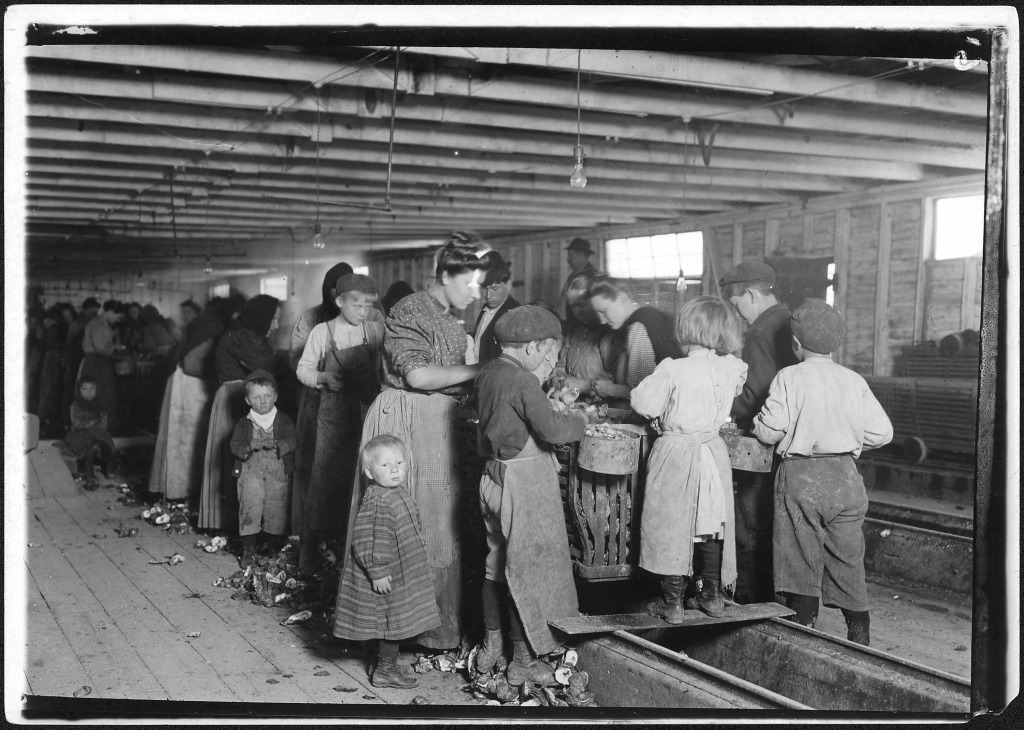

Or there’s the unnamed little girl shucking oysters in a canning factory, so small she has to stand on a plank to reach the table, while the rest of her family works around her. Only the baby had time to look at the camera.

The commercial canneries had to be supplied by agriculture which wasn’t particularly mechanized, so a lot of children were out in the fields harvesting at a frantic pace to meet the demand. This was a far cry from the agricultural labor that people glorified, the kind where the strapping boys learn hard work and diligence from their father on the family farm. These workers didn’t own the farm. There was no such thing as working hard so you could get ahead. There was just working hard to eat from day to day, and girls did it too. Such as Laura Petty, barefoot and filthy, but with a big smile that you can tell is barely holding in a huge personality.

Or Jennie Camillo who carries awkward-looking box on her shoulder.

And Maud and Grace Daly, still filthy and they look tired.

(Wikimedia Commons)

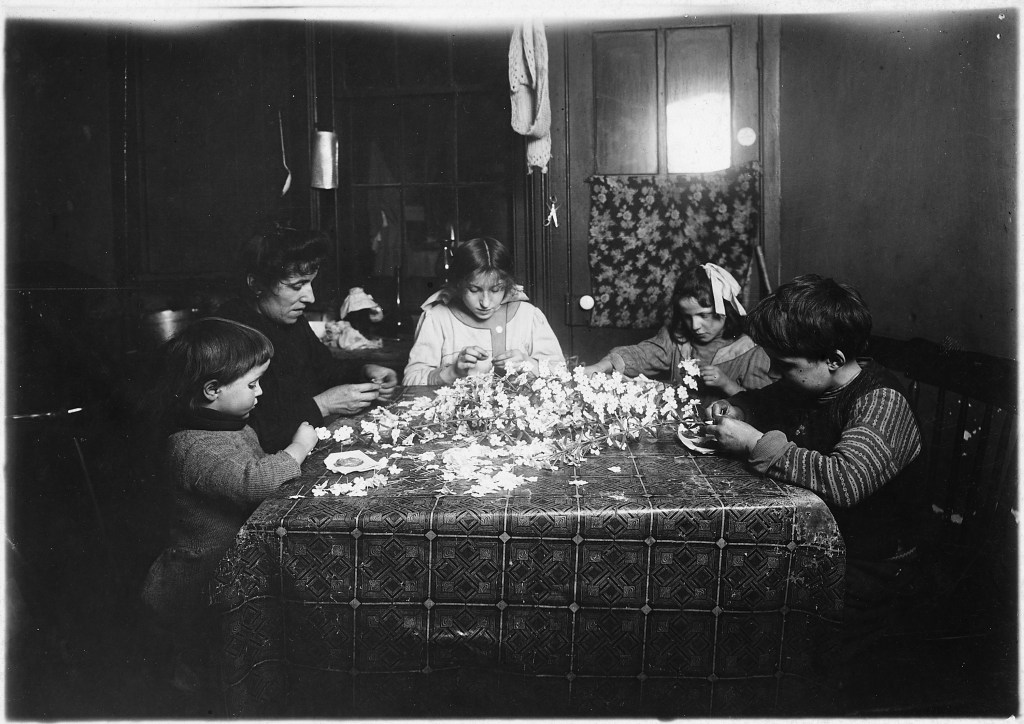

It had thus far proved next to impossible to regulate child labor in factories or fields. And it was far more impossible within private homes. Some employers found it simplest not to have any facilities at all, but simply send the work home, sweatshop-style, where whole families contributed long hours at a pittance.

In response to the public’s rising disapproval, employers insisted their workers were happy. For example, in 1908 mill owners produced a petition with hundreds of their employees’ signatures stating that they did not want child labor laws. Of course, a large percentage of those signatures were just X’s (Freedman, 38). These people had never had time to get even enough education to sign their own names, so who knows what they were told they were signing. Or what the consequences would have been if they hadn’t signed. Or whether they were offered a better option for their children. If they thought the other option was starvation, yeah, of course they signed.

Reformers claimed that having so many children in the labor force was precisely what forced wages down. Better to have adults (and especially adult men) doing the jobs and pay them a decent wage, but that was all hypothetical. The reality many families actually saw was that Father couldn’t get a job. Employers preferred kids. They were less likely to organize, more likely to obey, cheaper to pay, and entirely capable of doing an unskilled job. Children’s wages were not just additional income for many families. They were critical to survival.

Lewis Hines and others like him swayed public opinion enough that some progress was made before World War One, but it all got reversed when nations went to war.

After the War

Among all its other shortcomings, war is extraordinarily expensive. There was increased demand for goods of all kinds and seriously depleted manpower (Trattner, 152). But the war brought home another hard reality. In the US, 31% of all American men between 21 and 31 were rejected for the military because they were physically unfit. The number showed what a childhood of hard labor did to you. A full 20% of the men were illiterate. That was embarrassing for a country that called itself enlightened, and the numbers in other industrialized nations were almost as grim (Trattner, 154).

After the war, the child labor reformers got a little more traction. In the US, they wanted a constitutional amendment, but a constitutional amendment is not easy to get. Opponents claimed it was unnecessary or that the proposed language was too broad or that it violated states’ rights or that it was federal overreach or that it violated parents’ rights or that it was all a communist plot (Trattner, 170). The parent’s rights argument is particularly interesting because it’s classic politicking. The proposed amendment used the word “labor” which had always meant work for hire. But opponents said it meant you wouldn’t even be able to ask your teenage daughter to sweep the kitchen floor, for crying out loud, and that is overreach.

In other words, the opponents pushed the argument to a ludicrous extreme, so it was easy to knock down. It’s a strategy that politicians and pundits are still using today.

Besides, conservatives had by this point accumulated a stream of grievances and legislative losses: most notably women’s suffrage and prohibition. One legislator declared, “They have taken our women away from us by constitutional amendment; they have taken our liquor away from us; and now they want to take our children” (Trattner, 171). (Making yourself out to be the victim is another classic strategy.)

But such whining worked. The constitutional amendment never did pass (and still hasn’t), but in 1938 President Roosevelt signed the Fair Labor Standards Act. It did not actually ban child labor. But it did ban interstate commerce of any goods made by children under sixteen, which was almost the same thing. It also established a minimum wage, which made child labor less appealing to employers (Trattner, 204). The UK had already passed their own version, banning work for those under 14.

The Economic Reality of Child Labor

The reformers no doubt celebrated, but they actually don’t deserve all the credit. The Industrial Revolution created these jobs for children, but continued innovation and better machines meant there were fewer and fewer unskilled workers needed. Developed economies needed more and more educated workers (Trattner, 230). Which means both that there are fewer jobs for children and also that you are shooting yourself in the foot if you don’t send them to school.

Perhaps even more importantly, the Industrial Revolution created wealth. Not evenly or fairly. But there’s no doubt that the standard of living rose. One of the hallmarks of wealthy people throughout history is that they use their wealth to lengthen childhood for their own children. By that, anthropologists mean that rich people stretch the amount of time that kids do not have to be productive members of society. They can just be consumers, preparing for productivity. In the modern world, this means that childhood can possibly extend even into your thirties, depending on what degree you are pursuing. Then, when you are older, stronger, supposedly more capable, and carry a vast array of letters after your name, you enter adulthood with a serious advantage (Hassett, 346).

Okay, not all of us take it that far, but most of us are certainly extending that preparatory phase well beyond puberty.

Before and during the Industrial Revolution, children worked and no one complained because not working simply wasn’t an economic reality. There was no point in even thinking about it. So in many ways it is only because western society got significantly richer that anyone could seriously say Surely, we are rich enough to let all children actually be children? It largely wasn’t the poor who were saying this. Because it still wasn’t an economic reality for them. It was the wealthy and middle class growing more and more uncomfortable with the large discrepancy between their children’s lives and the lives of poor children who raised the issue.

Which goes a long way toward explaining why child labor is still a significant issue in developing countries. Even though the United Nations passed the Declaration of the Rights of the Child in 1959, the fact is that many girls and boys still don’t get education, adequate nutrition, freedom from exploitation, or any of the other things the UN declared as a child’s right (Humanium).The International Labour Organization estimates that 63 million girls were in child labor in 2020, and 29 million of them were in hazardous occupations. The estimates for boys are even higher (International Labour Organization).

What isn’t super clear from that report is that while most of these child workers are in Asia or Africa, some of them are much closer to my own home. Even the current child labor laws in developed countries have loopholes, not to mention straight up noncompliance, especially in agriculture. So many human rights watchers are still asking, Surely, we are rich enough to let all children actually be children?

Selected Sources

Anderson, E. (2018). Policy Entrepreneurs and the Origins of the Regulatory Welfare State: Child Labor Reform in Nineteenth-Century Europe. American Sociological Review, 83(1), 173-211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122417753112

Humanium. “Declaration of the Rights of the Child, 1959 – Humanium.” Humanium, 2011, http://www.humanium.org/en/declaration-rights-child-2/.

International Labour Organization. Executive Summary Child Labour. 2020, http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_norm/@ipec/documents/publication/wcms_800278.pdf. Accessed 15 Dec. 2023.

Trattner, Walter I. Crusade for the Children. Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Company, 1970.

Tucker, Barbara M. “The Merchant, the Manufacturer, and the Factory Manager: The Case of Samuel Slater.” The Business History Review 55, no. 3 (1981): 297–313. https://doi.org/10.2307/3114126.

UK Parliament. “Early Factory Legislation.” UK Parliament, 2019, http://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/livinglearning/19thcentury/overview/earlyfactorylegislation/.

Washington, George, and Benson John Lossing. The diary of George Washington, from to 1791: embracing the opening of the first Congress, and his tours through New England, Long Island, and the southern states. Together with his Journal of a tour to the Ohio, in 1753. Richmond: Press of the Historical Society, 1861. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/sd19000218/.

[…] that high is severely malnourished (Trussell, 499), which might tell you something about all those girls in factories and mills from episode 11.11? But it is important to note that the data are sketchy in all of this. Nobody was collecting […]

LikeLike

[…] The Great Depression sent record numbers of teens into high school because they couldn’t get jobs (Thompson). Also because child labor laws finally started having some effect. […]

LikeLike

[…] previously done the spinning, they had to find other options. If they lived in the right places, some of them became millworkers. At the beginning they were excited about that. Compared to spinning all day at home under the […]

LikeLike

[…] barely. Many descriptions of child labor in factories focus on textile factories. This is true of my own description in episode 11.11. But canning factories were right behind textile factories in the number of employees and sometimes […]

LikeLike