It was no less a person than Julius Caesar himself who first informed the natives of Britain that they were part of Rome now. That was in 55 BCE and then again in 54 BCE. Having done that, Caesar went back to Rome to tell the Senate how great he was, and many of them much agreed. Then he met Cleopatra, and the rest was last week’s episode. Britons went back to their lives. The difference was they were no longer off the edge of the Roman map.

Less than a century later, Emperor Claudius also needed to convince Romans just how great he was, and the legions were back in Britain. Unlike Julius, Claudius left the hard work of actual campaigning to his subordinates. When they reported that victory was near, he raced up just in time to accept all the credit. Which I suppose if you’ve got to do war at all is the most fun way to do it. Anyway, he was there in the flesh to accept the surrender of eleven tribal kings (Dudley, 41). One of those kings was probably the king of the Iceni, a tribe who lived in modern-day Norfolk, East Anglia (Collingridge, 105, 170).

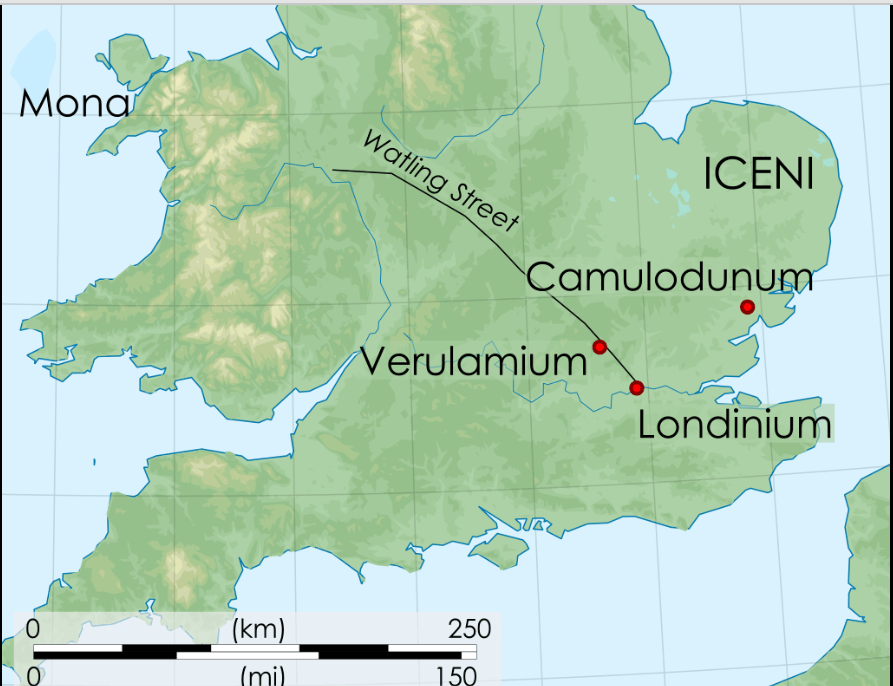

If you’re hazy on your English county map, then think of the island of Britain as roughly triangle shaped. Down in the southeastern corner, you’ve got the peninsula that comes closest to the continent. Just north of the peninsula, there’s a bulgy bit sticking out into the North Sea. The bulgy bit is East Anglia, and the northern part of East Anglia is the county of Norfolk.

Rome found it easier to absorb its conquests gradually, so these kings became client kings. That was a relationship that can’t be fully defined because each one was individually negotiated. Some paid tribute to Rome. All were liable for troops and supplies if Rome needed it. Most submitted to Roman ideas of city planning. Building projects were funded by the locals, whether or not they actually wanted the building project. In return, the savage barbarians were supposed to be grateful for the enlightenment of Roman culture, connection to the trade routes of luxury goods previously unavailable in their area, and the likelihood (but not the guarantee) of Roman military support should they be attacked by their neighbors tribes or face their own internal rebellion. That last, was generally why the kings agreed. (Dudley, 43; Collingridge, 12). Better to be a client king than not to be king at all.

Crucially, this negotiated relationship was between Rome and the local ruler. Not Rome and the local kingdom. When said ruler died, the whole arrangement was up for renegotiation (Dudley 43; Collingridge, 170). Which is exactly what happened in 60 CE.

The Death of the King

In that year, King Prasutagus of the Iceni died after a long reign. He left a will in which he clearly believed he had the right to settle his estate. He knew he had obligations to Rome and he settled those by leaving half his kingdom (half!) directly to Emperor Nero. The other half he left to his two daughters (Tacitus 14.31). This he believed would satisfy Rome and protect his family.

He could not have been more wrong. The local Roman authorities were outraged. Merely half of his kingdom was ridiculous. Prasutagus had no right, according to them, to will any part of his estate away.

One open question I have is whether it would have made any difference if Prasutagus had left his kingdom to a son, instead of to daughters. Romans found women in power to be abnormal and repulsive. But the classical sources do not even discuss that possibility. Maybe it wouldn’t have made a difference, but as it was, the Iceni were about to feel the wrath of Rome.

All the significant men of Iceni were stripped of their possessions and sold into slavery. Of particular note to us today, Rome exacted vengeance on the women of Prasutagus’s immediate family. His wife Boudica was flogged and his two unnamed daughters were raped (Tacitus 14.31).

This outrage is the first we hear of the woman who has been variously known as Boudica (with one c), Boudicca with two c’s), Boadicea, Bonducca, and a dozen other variations over the centuries. There’s even some doubt that the Celtic word at the root of that name is a name at all. It might be a title, meaning Victory or Victorious (Collingridge, 2).

Vengeance Is Hers

Unlike the majority of abused women in history, Boudica was far from powerless to strike back. She called for her people to rise up in rebellion and they flocked to her banner.

But no serious rebellion is ever simple and straightforward, with only one cause (like female rage). The account I have just given you is from Tacitus, a Roman historian who did not witness the events himself. But his father-in-law fought against Boudica, which means he was our closest source.

The other classical account, written later by Cassius Dio, doesn’t mention either flogging or rape. For him the motivations were economic. Claudius had given the Britons money seventeen years earlier in their initial negotiations. The local governor was now demanding repayment. Seneca the Roman businessman had learnt them enormous sums of money, which he was now demanding back with interest (Cassius Dio 62.2).

No one likes a creditor even when you understood the terms of the loan and can afford to pay it back. There is reason to suspect that the Iceni neither understood the terms nor could afford to pay. The Iceni were a coin-minting society. We have some beautiful surviving coins with Prasutagus’s name on them. But they likely didn’t have a fully monetized economy like we do. Most tribal societies are based on giving gifts to cement relationships of trust. They are not based on bankers lending money at interest. To demand a gift back and then some extra on the top is unbelievably rude in a gift-giving society (Collingridge, 177).

Furthermore, there is the tiniest hint in the archaeological record that all was not well, economically speaking. Ordinarily, Britain (and Iceni territory in particular) was rich in agriculture. Yet there is a little evidence that Romans in this year had imported wheat from the Mediterranean. You’d think they wouldn’t need to. If they went to that trouble, it is possible that something had gone wrong in the previous harvest or two (Collingridge, 220). Neither Tacitus nor Cassius Dio says so, but economic distress might well explain why Rome wanted a return on their investment so urgently. And it is equally possible that the reason the Iceni did not pay was because they could not pay.

Whatever the reason, men (and women) joined Boudica’s rebellion enthusiastically.

We know pretty much nothing about Boudica’s origins or how she came to marry the king, but Cassius Dio has given us a physical description of her. He says: “In person she was very tall, with a most sturdy figure and a piercing glance; her voice was harsh; a great mass of [tawny] hair fell below her waist and a large golden necklace clasped her throat; wound about her was a tunic of every conceivable color and over it a thick chlamys had been fastened with a brooch. This was her constant attire” (Cassius Dio, 62.2).

Cassias Dio never actually saw Boudica, so it’s hard not to suspect that he made most of that up for dramatic effect. The tawny hair has been variously translated as yellow or red, both of which are certainly possible. The tunic may well have been similar to a Scottish tartan. Weaves of that nature have been found all over northern Europe (Dudley, 54). The large golden necklace was also quite possible. One of the most spectacular archaeological finds in Britain is a golden torc from Iceni territory. You should definitely go to the website to look at a picture of it, for it has been compared with the crown jewels in sheer fabulousness. So much so that it was initially dismissed as a fake. In the words of Neil Oliver, “gold looks too much like gold to actually be gold” (Oliver, 261). But it is real. Sadly, it can’t be the same torc that Boudica wore. Its burial seems to have pre-dated her, but it is still proof that the description is possible and proof of Icenian wealth.

The essential point of this description was to emphasize Boudica’s strangeness to Cassius Dio’s Roman audience. Nothing about this savage woman would have felt familiar to them. But it was compelling to other Britons, for Boudica soon had allies.

The Trinovantes were the tribe in the southern part of East Anglia, and they had their own very similar grievance against the Romans. It was on their tribal land that the Romans had chosen to build their capital Camulodunum, which was now a thriving city populated by a great many soldiers who had finished their careers in the Roman legions.

Rome knew exactly how much of its success depended on convincing young men from across the empire to fight for them. Among other things, the army promised that if you finished an honorable career they would give you a land grant of your very own. Good policy from their point of view. It certainly worked as an inducement, but land doesn’t come out of thin air. It generally belongs to someone else already. In Camulodunum, these armed and battle-hardened legions were told to go pick out a homestead and simply eject the current occupants (Tacitus, 14.31). So you can see why hatred burned hot as Boudica’s army drew near. The Trinovantes were more than ready to join her. Cassius Dio says she gathered 120,000 soldiers (Cassius Dio, 62.2).

Burning the Capital

No one wrote down the Boudica’s decision-making process when she chose Camulodunum for her first assault. But it was a good choice. For one thing, it lacked physical defenses. Whether through misplaced confidence or sheer laziness, the Romans had not yet built any earthwork wall or ditch or anything else to slow down a marauding army. For another thing, it currently lacked active soldiers to defend it too. The bulk of the Roman army was clear on the other side of Britain, sacking the Isle of Mona off the northern coast of Wales (Cassius Dio, 62.7). Mona was a sacred isle to the druids. Sacking it might have been sort of like attacking the Vatican or Temple Mount. So it’s another reason for British rage, though it is unclear if Boudica knew what was happening there when she was bringing her army down on Camulodunum.

An army of this nature moves slowly. There was plenty of time for the few thousand residents to realize what was coming. The days of dread were filled with omens: the statue of the goddess of Victory fell down. The Senate and the theater were filled with spectral voices wailing. The waterfront looked red with blood (Tacitus, 14:32). It’s all very ominous and unnerving and possibly fanciful on Tacitus’s part, but also possibly not fanciful. In the very next section, Tacitus mentions that Boudica had secret accomplices in the city. Perhaps they engineered the omens (Tacitus 14.33; Dudley, 55).

When Boudica arrived, the entire city was plundered and then burned. Survivors took refuge in the newly constructed temple to Claudius, now dead and therefore divine. Boudica laid siege and after two days broke through to the Roman sacred space (Tac. 14:33). Tacitus leaves us to simply surmise what happened to those inside.

For a very long time, we were not entirely sure where Camulodunum was. No modern English city is known by that name. But in the 1920s, excavators in the city of Colchester gradually realized that what they were excavating was a Roman temple. And it turns out that the entire area has a layer of burned red earth at exactly the level for 60/61 CE (Collingridge, 199). The fire was intense and deliberate, but not entirely destructive. Archaeologists have found amphorae of olive oil and fine red pottery from the continent, an upholstered couch, two dice, plus figs, lentils, coriander, and flax (Collingridge, 201). Also the severed head of a statue of Claudius turned up in a river nearby, presumably chucked there by whichever Iceni warrior had hacked it from the body when the temple was sacked (Collingridge, 203).

What archaeology has not found is very much in the way of human remains. It is clear in the narrative that there was time to evacuate, and perhaps many people did. I hope so, because the alternatives are grisly. Tacitus is very restrained in his description, but Cassius Dio includes a more revolting detail. (If you’re a sensitive sort I suggest you skip the next few paragraphs.)

If you’re still with me, I regret to tell you that Cassius Dio says:

“The conquerors committed the most atrocious and bestial outrages. For instance, they hung up naked the noblest and most distinguished women, cut off their breasts and sewed them to their mouths, to make the victims appear to be eating them. After that they impaled them on sharp skewers run perpendicularly the whole length of the body. All this they did to the accompaniment of sacrifices, banquets, and exhibitions of insolence in all of their sacred places, but chiefly in the grove of Andate—that being the name of their personification of Victory, to whom they paid the most excessive reverence” (Cassius Dio, 62.7).

I would like to believe that Cassius Dio made up the most grotesque image he could think of because he was a Roman and he wanted to make the Britons look bad. That could be true. But history is full of otherwise decent people participating in the most unbelievable atrocities because they were desperate or hungry or afraid or thought they were following orders. It could be true. What stings is that a rebellion that began with very justified female rage should then perpetrate even worse abuses on women. But sadly, that too is not unknown unknown in history.

Anyway, if the victims were all marched off to a sacred grove for a ritualized murder then it’s not surprising that we haven’t found bodies in the city. We may never find them.

Burning London

By this time Camulodunum was a smoking ruin, and the Roman authorities across Britain had received word that they faced a serious problem. One they would very much rather not report to Emperor Nero back at home.

The main army was too far away to help, but smaller units were closer. The ninth legion in the East Midlands came to the rescue. Boudica cut them to pieces (Collingridge, 197).

She then swept south to the brand-spanking new Roman town of Londinium, known to you as London. Like I said, her army moved slowly, so she was actually beaten there by Suetonius Paulinius, the general and governor of Briain. Most of his soldiers, however, were still far away in Wales, and by his calculations saving Londinium was not an option. He ordered an evacuation and took with him any who could come. They were still running when Boudica burned London to the ground too, killing those who were, in the words of Tacitus, “chained to the spot by the weakness of their sex, or the infirmity of age, or the attractions of the place” (Tacitus, 14:33).

Boudica then turned north to Verulamium, a city that was not Roman, but full of British collaborators. Collaborators much like the very ones that the Iceni had been back when they were taking Roman money and leaving half their kingdom to Nero. Boudica torched them too.

Tacitus estimates that 70,000 died between the three cities that Boudica destroyed (Tacitus, 14.33). Probably that is an exaggeration, but there is no doubt that she was making an impression. The mighty Rome was taking a serious drubbing and both Cassius Dio and Tacitus make it clear that the shame was all the worse for coming from a woman.

On Boudica’s side, victory was great, but success was beginning to be its own problem. Cassius Dio says she now had 230,000 troops (Cassius Dio, 62.8), many of them not Iceni. The larger her army became, the harder it must have been to direct, to supply, to move. We don’t even know whether Boudica intended all this destruction. Possibly she ordered it. But equally possible, the enraged soldiers were spiraling out of control. And Suetonius Paulinius was only biding his time.

The Last Battle

The location of Boudica’s final battle is still unknown, but it was Suetonius who chose the location (Collingridge, 230). Neither army was particularly ready for a pitched battle, but both were under pressure from dwindling food supplies, and the British had their wives and families in wagons at the back of their vast host of fighting men (Tacitus 14.34).

Both Cassius Dio and Tacitus give an account of Boudica’s rousing battle speech and both of them invented the speech. We know for a variety of reasons. There are logistical reasons, like how could Boudica have made herself heard to such a horde without the benefit of a sound system (Adler, 178)). There are literary reasons, like how the speeches have Latin rhetoric and Latin alliteration and it is unlikely in the extreme that Boudica gave her speech in Latin or had the benefit of a traditional upper-class Roman education for boys (Collingridge, 235). There are logical reasons, like why would she find it necessary to insist that, yes, it was usual for Britons to fight under a woman. Clearly, if it was all that usual, she wouldn’t have needed to say it to her own troops (Tacitus 14:35). It was Roman audiences who needed such a strange thing explained. And there are political reasons, like when she gets sidetracked into a rant about Emperor Nero’s personal failings. I kid you not, the words “inferior zither player” are used as the final crushing condemnation (Cassius Dio, 62.6). A zither, in case you don’t know, is a generic term for a whole class of stringed instruments, and as a string player myself, I feel pretty confident in saying that Boudica neither knew, nor cared how well Nero played the zither. It was Cassius Dio who hated Nero and found inferior zither playing to be the most withering insult he could think of.

Tacitus’s version is just as apocryphal, but at least strikes the right dramatic spirit. You can imagine a swelling soundtrack in the background as you listen to her conclusion:

“It is not as a woman descended from noble ancestry, but as one of the people that I am avenging lost freedom, my scourged body, the outraged chastity of my daughters. Roman lust has gone so far that not our very persons, nor even age or virginity, are left unpolluted. But heaven is on the side of a righteous vengeance; a legion which dared to fight has perished; the rest are hiding themselves in their camp, or are thinking anxiously of flight. They will not sustain even the din and the shout of so many thousands, much less our charge and our blows. If you weigh well the strength of the armies, and the causes of the war, you will see that in this battle you must conquer or die. This is a woman’s resolve; as for men, they may live and be slaves.” (Tacitus, 14:35)

With that, the Britons charged into battle on their war chariots. The Romans waited until they were in range, and then let loose their javelins. They followed that up with a wedge-shaped column advancing and soon the cavalry charged in from the sides.

After a full day of fighting, the Britons broke and fled, but they were hemmed in by their own wagons full of their women, whom the legions killed just as efficiently (Tacitus, 14.37; Cassius Dio, 62:12).

As for Boudica, she did not die in the heat of battle. She must have somehow escaped because Tacitus says she took poison (Tac 14.37), while Cassius Dio says she sickened and died (Cassius, 62.12).

The Price of Defeat

Tacitus claims that Rome lost only 400 men. Well, 401 actually, for he adds that the prefect of the second legion, which had failed to arrive, was so dismayed at missing all this glory that he threw himself on his own sword (Tacitus 14.37). He also claims that 80,000 Britons died that day, which is a staggering number. If accurate, it was a one-day death toll that later militaries didn’t achieve until World War One, when we had much more efficient tools for butchering each other (Collingridge, 243). Of course, it probably isn’t accurate, but however many died, it was enough to break Boudica’s rebellion.

The Iceni kingdom was placed under direct military control. Its people were dead or scattered or sold into slavery. They had no more queens or rulers of any sort. They simply ceased to exist (Collingridge, 248). Rome ruled East Anglia and much of the rest of Britain for another 350 years.

For a long time, Boudica was mostly forgotten by the British. But the Renaissance brought revived interest in classical authors like Tacitus and Cassius Dio, and her name resurfaced with a variety of spellings. Elizabethans were proud of strong queens in the past. She began to enter the popular culture as a subject for plays and poetry, which makes me grumpy that Shakespeare never wrote a play called Boudica. His fabricated battle speech would have been epic. The Romantics found Boudica to be a worthy image of British nationalism.

The Victorians adored her as a symbol of glorious Britannia. They also had a queen whose name meant Victory. As a symbol of the age, Boudica makes no sense at all. She was a tribal leader who lost to an imperial power. By the 19th century, the British were playing the role of Caesar, Claudius, Nero, and Suetonius Paulinius. If anyone should have been throwing up statues of Boudica, it’s the people of India, Africa, and more, but never mind logic, Boudica played to British pride and stirred the emotions (Collingridge, 292, 306, 341). To this day if you visit London, you can see in front of the Houses of Parliament, a massive bronze statue of a Celtic war chariot, driven by Boudica, the last queen of the Iceni.

Selected Sources

Adler, Eric. “Boudica’s Speeches in Tacitus and Dio.” The Classical World 101, no. 2 (2008): 173–95. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25471937.

Cassius Dio. “Roman History, Vol. V.” Www.gutenberg.org, Translated In, 1906, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/10890/10890-h/10890-h.htm. Accessed 30 Jan. 2024.

Collingridge, Vanessa. Boudica : The Life of Britain’s Legendary Warrior Queen. Woodstock, N.Y., Overlook Press, 2007.

Dudley, Donald R, and Graham Webster. The Rebellion of Boudicca. London, Routledge And Kegan Paul, 1963.

GILLESPIE, CAITLIN. “The Wolf and the Hare: Boudica’s Political Bodies in Tacitus and Dio.” The Classical World 108, no. 3 (2015): 403–29. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24699652.

Oliver, Neil. A History of Ancient Britain. Hachette UK, 15 Sept. 2011.

Potter, T W, and Catherine Johns. Roman Britain. Berkeley, University Of California Press, 1992.

Tacitus, Complete Works of Tacitus. Alfred John Church. William Jackson Brodribb. Sara Bryant. edited for Perseus. New York. : Random House, Inc. Random House, Inc. reprinted 1942. http://data.perseus.org/citations/urn:cts:latinLit:phi1351.phi005.perseus-eng1:14.31

[…] of the previous queens I have covered, from Cleopatra to Boudica to Zenobia, would say this was the moment for raising an army. But in a move that shows just how […]

LikeLike

[…] I said last week about Lakshmibai, this was the point where Cleopatra, Boudica, Zenobia would have raised an army. Lili’u’s forces were already stronger than the […]

LikeLike

[…] people politically and militarily. These women have glorious movie-worthy plotlines. (See here, and here, and […]

LikeLike