Just in case any of you thought Palmyra was a small city in upstate New York, you should know that the original Palmyra is an ancient city in what is now Syria.

Though it sat surrounded by desert, Palmyra was rich because it had natural springs. It was an oasis city, sitting right along the Silk Road. Merchant caravans from both east and west passed through Palmyra and paid handsomely for the privilege of setting up camp and watering their camels.

For a long time, Palmyra managed to be neutral. It was a place where everyone was welcome to stop (so long as they could pay), without fear of either the Roman empire to the west or the Parthian empire to the east (Vaughan, 8).

But of course, that wasn’t going to last. By the time Zenobia was born around 240 CE, Palmyra was fully incorporated into the Roman empire.

It was still a very cosmopolitan place. It had Romans, but also Greeks and Jews and Aramaeans and Mesopotamians and Bedouins and Arabians. Arab wasn’t yet a cultural or ethnic identity people understood, but there were people from the Arabian peninsula (precursors of Arabs, if you like). (Andrade, 54).

Religiously, Palmyrenes worshipped gods from all these places, often interchangeably. So Zenobia may have worshipped at Palmyra’s impressive temple of Baal-Shamin, an Aramaean god, or at also impressive temple of Bel, a Mesopotamian god. The temple of Allat (an Arabian goddess) was smaller, but still important. When Palmyrenes wrote in Greek, they translated Allat as Athena (Andrade, 27). Palmyra certainly could have had Christians. It did not have Muslims for the simple reason that Muhammad hadn’t been born yet.

Linguistically, Palmyrenes spoke an Aramaic language, related to Hebrew. But Zenobia herself was said to also speak Greek, Latin, and even Egyptian and Arabic. Zenobia is her Greek and Latin name. In Palmyrene, she’s called Bath-Zabbai (Andrade, 62).

As per usual in ancient sources, childhood is irrelevant. Nobody mentions Zenobia’s. We don’t know who her parents were or which of all those ethnicities contributed most to her DNA. But most likely she considered herself Roman. Palmyra was a Roman colonia, a city of status. Most of its people were Roman citizens. It was a multi-racial ethnicity.

Marriage to the King of Kings

The first we hear anything about Zenobia is as wife of Odaenathus, the prince of Palmyra. Odaenathus ruled as a client king of Rome. Rome loved him. Or at least they gritted their teeth and pretended to love him because they couldn’t afford to do anything else. Third century Rome was a disaster. Among other problems Emperor Valerian led a campaign against the Persians and not only did he lose, but he also got himself captured and executed. No enemy had ever dared execute a Roman emperor before. That was a privilege Roman senators and generals liked to keep for themselves. To have an enemy do the same thing was humiliating.

Odaenathus, prince of Palmyra, took his army and hotfooted it after the Persian army, defeating them before they could return across the Euphrates. Thus Rome was avenged, the empire was secured, and Gallienus (the new emperor) named Odaenathus commander of the east (Andrade, 132). Odaenathus continued his campaigning eastward and the title he liked for himself was “King of Kings” (Andrade, 134).

The problem with success like that is that the more you succeed, the more other people are afraid of you. Gallienus was a weak emperor. He couldn’t afford strong subordinates. In 268 Odaenathus was murdered, as was his oldest son and heir. (This was not Zenobia’s son; he was from a previous marriage.) Gallienus is a likely suspect, but the word in the Roman sources was that Odaenathus’s own cousin did it and that Zenobia egged him on because she wanted her own son Vaballathus to inherit (Historia Augusta, (The Thirty Pretenders), section 30).

The truth is more than one person had a motive here, the evidence is long gone, and the accounts conflict. We’ll never know for sure. The point was Zenobia was now a widow, and her son Vaballathus inherited Palmyra.

But Vaballathus was still little (about 10 years old), and that is where widows get their chance. And also, in some cases, their motivation. As a young and vulnerable prince of Palmyra, he too was a target.

Widow, Mother, Ruler

Zenobia set about protecting him. She proclaimed him king of kings and installed herself as regent (Andrade, 165-166). Palmyrenes seem to have accepted this without batting an eye.

Rome was less pleased, but they had other problems. Gallienus had inherited a mess, and under his reign, it remained a mess. The Historia Augusta, one of our best sources on this period was not written by a fan of Gallienus. In fact, the author says:

Now all shame is exhausted, for in the weakened state of the commonwealth things came to such a pass that, while Gallienus conducted himself in the most evil fashion, even women ruled most excellently.

Historia Augusta, (The Thirty Pretenders), section 30

I mean, ouch. That burns.

Zenobia is, of course, the woman he means, and yes, she was doing a just fine job. Nor was she trying to break with Rome. She continued to send Rome its taxes, which were not trivial (1/4 of all the caravan trade) (Andrade, 40).

When Gallienus got stabbed to death just a few months later, Claudius II came to the throne and Zenobia dutifully had her coin mint switch to producing coins with his image (Andrade, 172). But it didn’t help her. Claudius declared her a usurper anyway, and it’s entirely possible that it was his court that began the rumors that she had murdered her husband (Andrade, 152, 166). It made good propaganda since Odaenathus was such a Roman hero.

The truth was Claudius planned to rule the east himself, and he didn’t want anyone of any gender doing it for him. Zenobia could have rolled over and said all right then, if that’s the way you feel about it. But she didn’t. She chose to go on the offensive instead.

Expanding the Empire

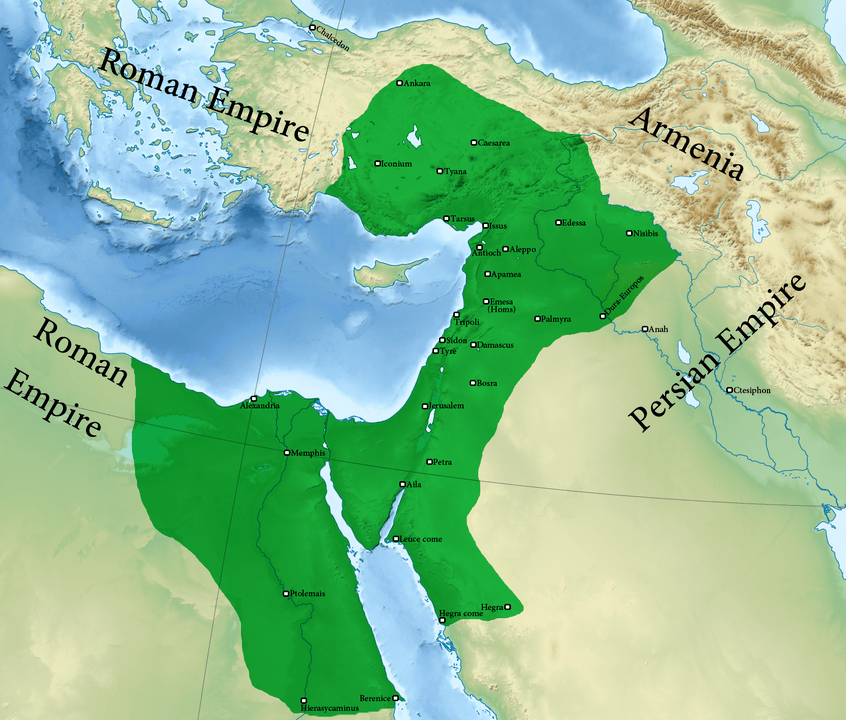

To challenge Rome’s power, she had to be too big to fail, too powerful to intimidate, too wealthy to outspend. Palmyra, the oasis city, did not fit the bill. She began seizing Arabian provinces starting in 270.

It would be fabulous if we had an account of her thoughts and strategy at this point, but we do not. The moral of the story here is that if you don’t want your enemies to write your story, you should write it yourself. Our accounts are all Roman. Palmyrene was absolutely a written language, but they, like so many others, did not leave us a great body of histories, dramas, and epic poetry. They only leave us inscriptions, like a surviving one which reads:

For the life and victory of Septimius Wahballath* Athenodoros, illustrious king of kings and epanorthotes of all the East, son of Septimius Odainath, king of kings, and for the life of Septimia Bathzabbai, illustrious queen, mother of the king of kings, daughter of Antiochus, mile 14

(Andrade, 8)

*Wahballath is an alternate spelling of Vaballathus

As a human interest story, it lacks something, but it’s quite a mouthful for a mile marker, which is what it is. You just have to read in the human interest bit by watching how these begin to expand after 270. There’s a lot of miles on the road to Egypt, and that was what Zenobia had in mind.

Her general Zabdas led 70,000 soldiers and took Alexandria for his queen. Then the Roman prefect came home and took it back. Then the Palmyrene army came and took it for a second time. By 271, Zenobia was appointing administrators for her new Egyptian province and official papyri were labeled as being under the joint rule of Vaballathus and Aurelian.

Who’s Aurelian? He’s the new emperor of Rome. If it seems like we’re going through emperors like tissues in hayfever season, it’s because that’s exactly what we are doing. I didn’t even have time to mention Quintillus who lasted only a few weeks.

Anyway, now we’ve got Aurelian, as merely the latest in a growing list of powerful men who are not at all pleased with Zenobia. He certainly didn’t recognize the 11 or 12 year old Vaballathus co-ruler of anything, especially not Egypt, the bread basket of the empire.

You do kind of have to wonder why Zenobia included Aurelian at all on these official papyri, but it seems she was still trying to preserve the fiction that she ruled on Rome’s behalf, hoping that Aurelian would be too busy with other problems to put up any serious resistance (Andrade, 178). In the meantime, she also had an army up in Asia Minor, expanding her empire in the other direction at the same time.

Back at home, the great colonnade of Palmyra, a main thoroughfare lined with columns and arches, received a new inscription, which said in both Greek and Palmyrene (more or less): “Septimia Zenobia, most illustrious pious queen. The Septimioi Zabdas, the chief general, and Zabbaios, chief of the army at Tadmor, honor their lady” (Andrade, 179 (I mixed the Greek and Palmyrene versions)).

The Greek word basilissa there can be translated as empress, rather than queen, but it was not the term used for empresses of Rome. That word was augusta, the feminine version of augustus, the title Aurelian currently held. Zenobia waited all the way until 272 (the following year) to claim that one. There’s an inscription that reads: “For … Septimia Zenobia Augusta, mother of [our] eternal lord, imperator Vaballathus Athendorus” (Andrade, 191).

Zenobia had just declared herself not merely a queen of queens under a Roman emperor, but the emperor’s equal. Just why she decided this now is unclear because the dates are unclear. Possibly she declared that, and then Aurelian sent his army in response. Or maybe she declared that because Aurelian had already sent his army. Either way, there was no hope of reconciliation now.

Open War

Aurelian marched across Asia Minor and retook it easily. Zenobia wasn’t really fighting for it. She was waiting for him in northern Syria.

The first major clash was just north of Antioch in May or June of 272. The Palmyrenes were heavily armored, but the Roman cavalry played them. They ran just out of reach until the Palmyrenes were exhausted in their heavy armor. Then the horses turned and crushed them into the ground (Zosimus, 1.50.3; Andrade, 200)

It was a disaster for Zenobia, but she wasn’t done yet. In one of the most audacious bits of show business in history, Zenobia hatched a plan. She needed to get well away from Antioch before anyone in town realized that Rome was the power to please here and handed her over to them. So, while Aurelian’s army mopped up north of town, Zenobia simply declared victory. She even—get this—found some poor chump to impersonate Aurelian and had him paraded through town as her prisoner. While the townspeople were cheering and partying, she and her general Zabdas scooted it south out of town at top speed (Andrade, 200). The parties were probably still going on when the real Aurelian showed up at the gates with his army.

Some conquerors take the view that you’ve got to be brutal to towns you take because fear keeps the ones you’ve already got in line. Aurelian took the opposite view. His theory was you grant mercy to towns you take because it encourages the next town to surrender quickly.

And it worked for him. Units all across Syria defected to Rome. Meanwhile another Roman army retook Egypt. (Andrade, 201-202). The switch was not hard for these people. They had been Roman before, then very briefly Palmyrene. Now they were Roman again.

Zenobia fought and lost another battle at Emesa, and now she was down to only the city of Palmyra itself.

Palmyra had no treasury left. It also had no city walls. All it had going for it was desert on every side that made it hard for an approach.

Hard, but not impossible. Aurelian’s army was moving forward and many in Palmyra thought their best plan was to surrender and hope for some of that famous Aurelian mercy. Zenobia did not think that mercy was going to extend as far as herself. She fled east on a female camel. The sources make a big point about that female camel, leaving me to wonder whether there’s something about female camels I don’t know. She made it many miles across the desert to the Euphrates river, but she got caught there and brought back.

The Price of Defeat

And here we have a curious twist of being female in a patriarchal world. As long as Zenobia was winning, the sources describe her as very masculine. The Historia Augusta uses phrases like “her voice was clear and like that of a man” ((The Thirty Pretenders), section 30), and another writer Zosimus says she “had the courage of a man” (1.39.2).

But as soon as she had lost, everyone is at pains to explain how feminine she is. Edward Gibbons author of the 18ᵗʰ century History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire manages to be the very most insulting. He has praised her to the skies up until this point. Now he says:

But as female fortitude is commonly artificial, so it is seldom steady or consistent. The courage of Zenobia deserted her in the hour of trial; she trembled at the angry clamors of the soldiers, who called aloud for her immediate execution, … and ignominiously purchased life by the sacrifice of her fame and her friends.

Gibbon, volume 1, Chapter 11, part 3

Zosimus agrees that Zenobia escaped death by blaming the whole escapade on her male friends and advisors. They had “seduced her as a simple woman” (1.56.2). The scholar Longinus definitely got executed, and general Zabdas disappears from the record, so he was a likely victim too (Andrade, 207).

Now, I will allow that it is certainly possible that Zenobia betrayed her friends and played the just-a-dumb-woman card. It’s not admirable, but fear of death is fear of death. I will even grit my teeth and allow that it is possible Zenobia really was a manipulated woman. These men might have been the real power behind the throne. But Zosimus gives a little hint about another possibility. Before he gets to anything Zenobia says about being a simple woman in captivity, he says that Aurelian “became uneasy at the reflection that in future ages it would not redound to his honor to have conquered a woman” (1.55.3).

You see it? It was better for Aurelian to blame her advisors. There was no shame in having suffered temporary losses before crushing a group of rebellious men. That happened all the time. It was sort of glorious. A woman was something else again. He was primed to believe that Zenobia was not and could not have been the intellect or the power behind the Palmyra episode. He did not want to believe it. Therefore, it must have been her advisors. They died. Zenobia lived.

Aurelian returned to Rome in triumph, and he took Zenobia and her children with him. Here we get diverging accounts. Zosimus says Zenobia died en route, either of disease or starvation (1.59).

The Historia Augusta gives her a much longer life. According to it, she made it to Rome, where she initially received the treatment Cleopatra had killed herself to avoid.

She was led in triumph with such magnificence that the Roman people had never seen a more splendid parade. For, in the first place, she was adorned with gems so huge that she laboured under the weight of her ornaments; for it is said that this woman, courageous though she was, halted very frequently, saying that she could not endure the load of her gems. Furthermore, her feet were bound with shackles of gold and her hands with golden fetters, and even on her neck she wore a chain of gold.

The Thirty Pretenders, section 30

Afterwards, it goes on,

Her life was granted her by Aurelian, and they say that thereafter she lived with her children in the manner of a Roman matron on an estate that had been presented to her at Tibur.

The Thirty Pretenders, section 30

Yes, it turns into a sort of happily ever after, which was an unexpected twist. So unexpected that it’s tempting to assume it’s just wrong. We cannot prove either way, but there is some slight evidence that it might be true. Subsequent generations of Romans from that area have names that might indicate they might possibly have been her descendants (Andrade, 210).

Palmyra, Then and Now

As for the kingdom of Palmyra, it never rose again. They tried another revolt the following year, but Aurelian came back and wasn’t so merciful that time. The caravan trade was routed differently and it lost much of its wealth (Andrade, 217). Over the centuries, it became a Christian city and then a Muslim one.

In the 17ᵗʰ century European tourists realized what a forgotten gem Palmyra was. The Great Colonnade, the temple of Baal-Shamin, the temple of Bel, the stone lion of the goddess Allat, the Roman amphitheater! The very buildings and monuments where Zenobia herself had once walked and worshipped and ruled, they were all still there, looking glorious. A great many of the smaller artifacts went home in European pockets, but the city continued to attract tourists and archaeologists (Andrade, 219-220).

That kind of staying power is what makes the current situation. In May of 2015, Islamic State or ISIS took Palmyra. They killed the director of Palmyra’s Antiquities and the Palmyra Museum (Andrade, 215). Then they proceeded to destroy the monuments that had stood there for almost 2000 years. The temples of Bel and Baal-Shamin, they blew up. The arches on the Great Colonnade are no longer there. The lion statue of Allat was toppled and her nose broken off (Allen). The Roman theatre remained intact, and in 2015 the world knew it was intact because ISIS released videos of it. They were using it as a staging ground for executions (Allen).

Every faction in Syria has been eager to claim Zenobia the great Syrian heroine, and her story is a potent symbol of resistance to Western imperialism and culture. That is exactly what she was. But they’ve used her for propaganda, even while destroying her city and slaughtering its people. I’ll leave you to decide what Zenobia would have thought about that.

Selected Sources

Allen, Paddy, et al. “Palmyra after Isis: A Visual Guide.” The Guardian, 8 Apr. 2016, http://www.theguardian.com/world/ng-interactive/2016/apr/08/palmyra-after-islamic-state-isis-visual-guide.

Andrade, Nathanael J. Zenobia : Shooting Star of Palmyra. New York, Oxford University Press, 2018.

“ASOR PHOTO COLLECTION – American Society of Overseas Research (ASOR).” American Society for Overseas Research, 29 May 2020, http://www.asor.org/resources/photo-collection#pc-syria. Accessed 23 Feb. 2024.

Gibbon, Edward. Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,. Project Gutenberg, 1996, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/25717/25717-h/25717-h.htm#chap11.3. Accessed 23 Feb. 2024.

Historia Augusta. Translated by David Magie, Loeb Classical Library, 1921, penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Historia_Augusta/home.html. Accessed 22 Feb. 2024.

Kershaw, Stephen. The Enemies of Rome. Simon and Schuster, 7 Jan. 2020.

Vaughan, Agnes Carr. Zenobia of Palmyra. Doubleday, 1967.

Zosimus. “New History Book 1.” Www.livius.org, Livius, 2019, http://www.livius.org/sources/content/zosimus/zosimus-new-history-1/. Accessed 22 Feb. 2024.

The feature image is by Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=126112516

[…] of the previous queens I have covered, from Cleopatra to Boudica to Zenobia, would say this was the moment for raising an army. But in a move that shows just how much the […]

LikeLike

[…] I said last week about Lakshmibai, this was the point where Cleopatra, Boudica, Zenobia would have raised an army. Lili’u’s forces were already stronger than the Provisional […]

LikeLike

[…] He could have said that Rome crushed an enormous number of their neighbors, and some of their most famous opponents were women who led their people politically and militarily. These women have glorious movie-worthy plotlines. (See here, and here, and here.) […]

LikeLike

[…] 31. 12.4 Zenobia, Last Empress of Palmyra (Syria) – Her Half of History, https://herhalfofhistory.com/2024/03/14/12-4-zenobia-last-empress-of-palmyra-syria/ 32. Zenobia | Queen of Palmyra, Syria, Death, & Facts | Britannica, […]

LikeLike