I’m sure you’re aware that queens reigning in their own right are fairly rare. Still, they are common enough that everyone can name a few (or at least certainly hope so). Far rarer is when you get one reigning queen directly following another reigning queen, for two in a row. Still, that has been known to happen, most famously from Mary to Elizabeth I of England, but it’s also happened in Korea and Japan and a few other places. Three queens in a row is rarer still, but it has happened in the Netherlands. It even happened in England if you count Jane Grey, who was debatably queen for nine days in between Mary and Elizabeth. Russia has the same debatable problem.

And what about four queens in a row? The Kingdom of Aceh first caught my notice because I read that it had the only run of four successive reigning queens in history. As with most superlatives, that turned out not to be quite true, but it is nonetheless really, really rare, and worth explaining how such a strange thing happened.

The Kingdom of Aceh

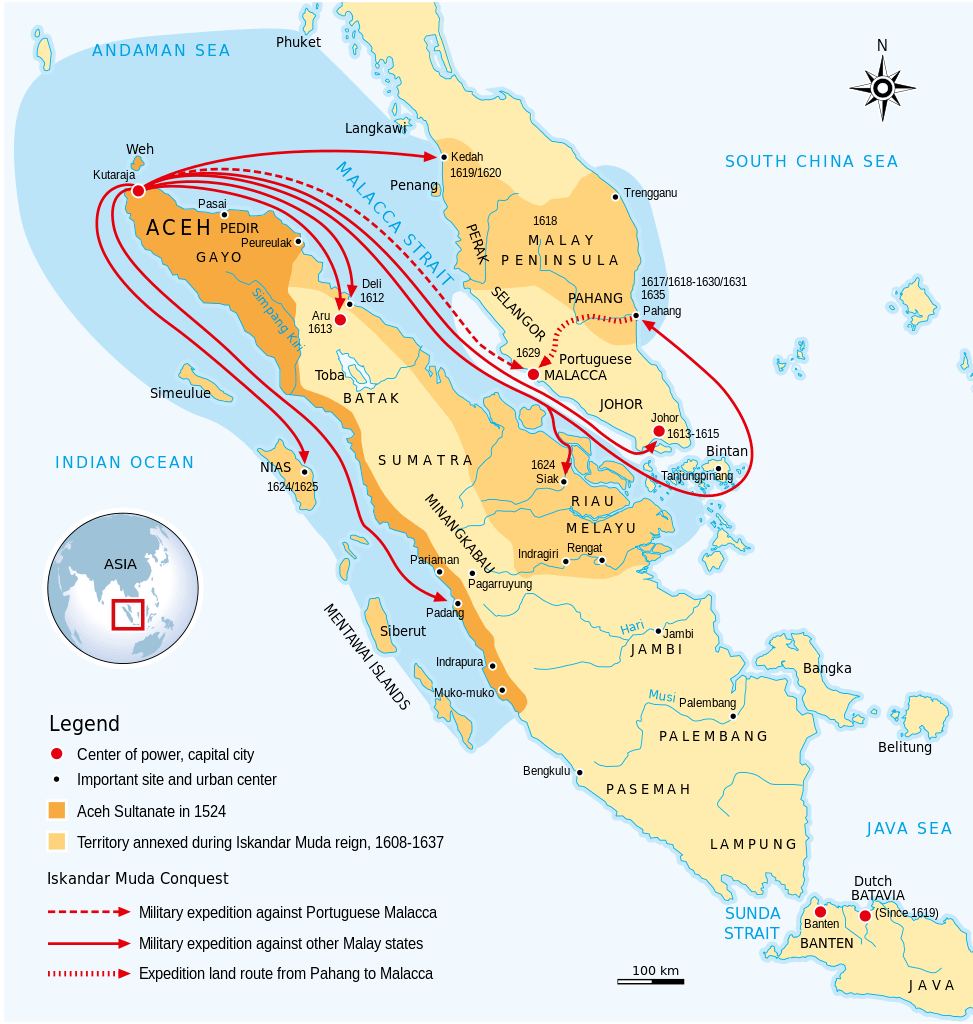

The Kingdom of Aceh was on the northernmost tip of the island of Sumatra, the largest island fully within the modern country of Indonesia. There still is a province of Aceh in the same place.

The Kingdom of Aceh was founded in the 16th century in an area that was already staunchly Islamic. They had a completely predictable string of male sultans with varying degrees of brilliance, culminating in the reign of Iskander Muda, who a great conqueror of the neighboring kingdoms and is generally considered the highpoint of Aceh history.

While we have a list of the preceding sultans and some of their deeds, we generally don’t know why they attained the throne, or (in some cases) why they lost it. They certainly do not seem to have followed strict primogeniture to determine the next sultan (Khan, 30).

Iskandar Muda left no son anyway, so that option was out. But he did designated his own successor, choosing his son-in-law, the foreign born Iskandar Thani. The problem was that Iskandar Thani botched it. He lost some of the territory the great Muda had won, and he alienated the Acehnese elites. In 1641, said elites got rid of Iskandar Thani by methods unclear. I’ll leave you to ruminate on the various possibilities.

Anyway, they needed a new sultan, Thani didn’t have a son, and with or without clear succession rules, this is often the point where civil war breaks out.

Safiatuddin, the First Queen

The closest thing there was to a set of rules was the Aceh Canonical Laws, of which only a much later version survives. But what we’ve got is based on an earlier document and so we’re gonna use it, assuming that the people of Aceh were familiar with the same concepts. The required qualifications for a sultan were that “a candidate had to be a Muslim of good lineage, an adult … , an Acehnese citizen, courageous, wise, just, loving and soft-hearted or merciful, conversant with the nuances of language, a keeper of promises, not physically handicapped, truthful, loving, patient, restrained …, forgiving, firm and yet submissive to Allah’s will, and thankful to Allah” (Khan, 27).

That is a mighty high standard to reach, and one can’t help wondering whether even the great Iskandar Muda really measured up. Especially to the loving bit, which is so important it’s in there twice.

But the thing that is conspicuously missing is any gender requirement. Now it’s true enough that the probable reason for not including it was that the original author maybe never even considered women as a possibility. One doesn’t need to state the obvious. Nevertheless, the loophole was there.

We know that women played active and public roles in Aceh culture. Both Iskandar Muda and Iskandar Thani were, for example, protected by a corps of female guards (Khan, 51).

The wider regional area also had a number of queen regnants (Khan, 42), though there had never been one in Aceh. What is clear in the Aceh histories is that however loving, courageous, wise, or just a candidate might be, what he or she really needed was the support of the council of nobles (called the orang kaya) and the religious scholars (called the ulama). And what these groups really didn’t want after the disaster of Iskandar Thani was another foreign-born prince. They preferred his widow, a born and bred girl from home, the daughter of the great Iskandar Muda. Her lineage, age, and citizenship were top notch. One presumes she was also loving, courageous, wise, just, and all the rest of it. Thus the first queen, Safiatuddin, was chosen in spite of her gender (Khan, 38).

She ruled for 35 years to great success, and it is just my bad luck that this isn’t a series on First Queens because of the four queens of Aceh, we know the most about her.

Having installed her, the Acehnese realized that having a queen rather than a king was a positive benefit. A female ruler was not part of the entirely male orang kaya. She was not in any of the competing political factions, so she could judge neutrally between them. The political murder rate (which had been high) went way down (Khan, 255).

When Safiatuddin died of natural causes, the elites decided the experiment had been a success. The transition does not even seem to have been disputed as a second queen and then a third queen took their turns, both of whom also died of natural causes.

In 1688, it was time for a fourth queen, and one faction of the elites immediately chose a young woman to fill that role (Khan, 249). This was Zainatuddin Kamalat Syah, our heroine for today.

A Contested Coronation

However, the situation had changed somewhat.

While the country had been Muslim for centuries, Aceh was certainly not in the heartland of Islam. They were not Arabs. In 1683 a group of Arabs had arrived in Aceh, and they had great influence and commanded enormous respect.

Like every other great religion, Islam sometimes has trouble distinguishing between doctrine and culture. The lines get blurred, and this group of Arabs were not at all sure about the legitimacy of having a female ruler (Khan, 202, 249, 251). It was not a concept they were familiar with. It didn’t happen where they were from. At least, not recently. Not in their living memory.

Under this influence, a second faction of the elites (called the priests’ party) protested the appointment of Kamalat Syah. They preferred to have a sultan, not a sultanah, not a queen. Some of the highlanders agreed, and they sent 5-6000 men down to the port city to protest (Khan, 249-250).

One contemporary called this a civil war, which is a pretty inflammatory label for what amounted to two nights of shouting at each other (Khan, 250). There are democratic countries today who just call that all in the normal course of business for Parliament.

Anyway, in the end, everyone went home and Kamalat Syah was installed as the fourth queen.

A Contested Reign

But it’s not like the opposition just gave up. The priests’ party wrote to Mecca to seek a fatwa on the subject. A fatwa is a legal ruling by a qualified Islamic judge on any question that is presented to them. In this case, the question was: Can an Islamic country be ruled by a woman?

I am tempted to say, well, obviously yes. Because Aceh already had been for 48 years by this point, and let’s not forget Arwa from last week. There are other cases too. Besides all that, there’s the fact that even posing the question for a fatwa means that the Qu’ran does not make a clearly definitive statement on the subject, and nor did the hadith, the attributed reports of what Muhammad said and did. If these sources had made a clear statement, no one would have needed a fatwa to answer the question. Nevertheless, the fatwa came back and the answer was no, a woman ruling a country is contrary to Islam.

Even that might not have been a death knell. It was possible to ignore a fatwa, or even to seek out a second opinion if you didn’t like the first one. However it is likely that there was another factor in the demise of Aceh queenship. The first queen, Safiatuddin, had been a childless widow when she took the throne.

An unmarried king can use marriage to his advantage, using it to cement or forge alliances. An unmarried queen can do no such thing. In a patriarchal world, a husband is an entirely destabilizing element for a queen regnant. As a wife, her freedom of action is limited, while the husband may well expect rights that his wife’s subjects are in no mood to grant to him. The situation is bound to be difficult and quite possibly fatal. There is a reason why Elizabeth I, the Virgin Queen of England, remained a Virgin Queen throughout her life, and she’s not alone. Of the seven queens so far in this series, a full six of them were widows, and the seventh (Jinseong) left no mention of a husband. Of the six widows, only Arwa definitely remarried and that was probably only under orders of the caliph. And then there’s Cleopatra whose relationships are so complex they cause dizziness, but for sure she never allowed any of the men in her life to interfere in Egypt. None of the women in series two on Women Who Seized Power did so with a living husband either. Basically, if you want to rule a country, a husband is just not an asset.

Safiatuddin never remarried, which means she had no legitimate children. She didn’t have any illegitimate ones either. Her chastity was a matter of state concern, a problem that male kings rarely have.

Obviously the second queen was not her daughter. In fact it’s unclear exactly who queens two, three, and four were. Presumably they were of sufficiently high rank that no one challenged them on lineage grounds, but this was no mother-to-daughter line of succession. It couldn’t be.

Queens two and three were elderly by the standards of the day when they took the throne. Possibly they had never married. Possibly they were widows. Either way there was no husband to muddy the waters.

Kamalat Syah was young. Which allowed young men to hope and quite possibly Kamalat did too. Not everyone would choose a throne over a family and a relationship. In fact, I think most women would not. We do not know for sure that Kamalat Syah married. But it’s considered quite likely. What we do know for sure is that in 1699, after eleven years on the throne, Kamalat Syah was deposed, and replaced with a man, whom every source takes pains to point out was of Arab descent. One possibility is that he was her husband. But that is speculation, not verified fact.

And so ended 59 years of female rule in Aceh.

Strong Queens? Or Weak Queens?

There are sharply divided views on just what we are to make of this whole unusual situation. The traditional view is that Aceh’s golden age was under Iskandar Muda and a series of weak queens just dragged everything down.

Most of our sources for the whole period come from foreign visitors to the court of Aceh, and that negative viewpoint was certainly shared by some of them. Perhaps the most scathing was the one written by the Persian diplomat in 1685, shortly before Kamalat Syah took power. He was definitely under the impression that the four queens were mere figureheads while the male elites ran things from behind the scenes. He wrote:

“Thus, the councillors kept the reins of power in their own hands and governed the island without any problem. Their hypocrisy did not balk at this unmanly solution. They simply hid their heads under a female kerchief of shamelessness and disloyalty. These women-hearted men of state seated the maiden of their virgin thought on the throne of deception and from that time on this kingdom … has been given to Houri-like beauties, women as charming as angels.”

(quoted by Sher Banu A.L. Khan in Sovereign Women in a Muslim Kingdom : The Sultanahs of Aceh, 1641-1699, p. 252)

More recent scholarship, however, has challenged the assumptions behind that view.

It is true that the four queens were not great conquerors like Iskandar Muda. It is true that they lost some of his conquests. Until recently, expansion was the mark of a strong country. It was expected. It meant you were doing well. But in the modern world, terrorizing your neighbors isn’t the mark of a good ruler; it’s actually part of the definition of a bad one. What counts as a good ruler now is one who provides peace, prosperity, and stability for the folks at home. And by that standard, female rule of Aceh was stunningly successful.

In 1688, when Kamalat Syah took the throne, a foreign traveler wrote that the city of Banda Aceh was the largest, richest, and most populated city in all of Sumatra, with 7-8,000 houses in the city alone, and hardly a moment when there were not a dozen ships from many nations clustered in the port, eager to do business (Khan, 261).

You cannot say that the queens merely got lucky to rule in a time of easy prosperity. In 1600 Southeast Asian countries traded as equals with Europeans, but the balance of power was shifting, and the time of our queens was one of rampant European expansion.

The Dutch East India Trading Company was the worlds’ first joint-stock company and when I say company, you are probably getting the entirely wrong idea. This company (generally known as the VOC, their acronym in Dutch) minted their own coins, judged and executed criminals, waged war, and established colonies. They frequently made business deals with the help of superior firepower. They were not so much a company, as they were a traveling foreign state. Many of our records about Aceh are in Dutch.

Later in the century, Dutch power was waning, but the English were more than willing to pick up the slack. Throughout the century, southeast Asian kingdoms fell like dominoes, but at the end of the century, the female-led Aceh had just had its longest period of political stability ever. They maintained their hold on the trade of pepper, gold, and elephants (Khan, 263). In particular, Safiatuddin outmaneuvered the Dutch, managing to keep them completely out of the elephant trade (Khan, 21), and Zakiatuddin (queen number three) refused the English permission to build any fort of any kind in Aceh for any amount of money (Khan, 170). There is no evidence that either of them were mere figureheads for the elite men (Khan, 7), and some to suggest they were active rulers, especially Safiatuddin, about whom we know the most.

One visitor during Kamalat Syah’s reign declared that she had hardly any authority, having to await interminable council meetings to make decisions. One has to wonder how a foreigner was in any position to know that (Neimeiger, 7), but even if true as reported, it’s hardly surprising that her position was tenuous. She was three years from being deposed. It is not an accurate depiction of the entire 59 years of female rule as has sometimes been claimed.

Religiously and culturally, Aceh was a center for Islamic studies and learning under the four queens (Khan, 208). Though none of the four appear to have intruded into the exclusively male roles at the mosques, they most certainly did encourage and collaborate with the ulama (Khan, 207-208). Meanwhile, they took the religious title of Khalifah, same as their male predecessors, and emphasized that they were chosen by Allah with a sacred duty to uphold Allah’s laws (Khan, 45). One suspects that Safiatuddin in particular would have been very surprised to hear that her religion forbade her to be queen. She thought she was following her religion quite well.

All in all, there is a serious argument to be made that the golden age of Aceh was not under Iskandar Muda, but under its four queens. As for Kamalat Syah, she did not live long after losing the throne, probably only about a year, dying under circumstances that are unknown.

Selected Sources

Khan, Sher Banu A.L. Sovereign Women in a Muslim Kingdom : The Sultanahs of Aceh, 1641-1699. Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 2017.

Niemeijer, Hendrik E. “Maritime Connections and Cross-Cultural Contacts between the Peoples of the Nusantara and the Europeans in the Early Eighteen Century.” Jurnal Sejarah Citra Lekha, vol. 1, no. 1, 27 Feb. 2016, pp. 3–10, ejournal.undip.ac.id/index.php/jscl/article/view/11856/9069. Accessed 22 Mar. 2024.

[…] Portuguese or the Dutch versions, both of whom were rolling in spices and gold from Indonesia (see episode 12.8 on the last queen of Aceh). So instead the English were forced to content themselves with lesser things. Like a little […]

LikeLike