To cover the history of hair would be a podcast in and of itself, and the host should not be me. My relationship with my own hair is best described as strained. My knowledge of how to style hair can best be described as seriously uninformed. That last is something I have in common with most historians, who have mostly ignored hair. It falls neatly into the category of frivolous and unimportant, much like everything else about women’s lives, so the records are lacking.

But they are not nonexistent. And hair has been very, very important to a great many women, both past and present, so I am going to give it a go, hitting only the points that caught my eye.

I don’t like superlatives like “oldest” because they are so easily proved wrong, but certainly one of the oldest depictions of a woman who may have styled her hair is the same 30,000 year old statue of the Venus of Willendorf which I mentioned a few weeks ago. I have now read that her hair is braided, which came as a surprise to me. If I had thought about it at all, which I didn’t, I would have said her hair is short and curly. I still think that might be it, but it could also be cornrow braids, which right from the getgo raises an interesting question. What texture was her hair?

Willendorf is in Austria, which conjures up a certain stereotypical image for me, and it’s not the same as the one I get when I think about cornrow braids. By the way, even that name “cornrow” betrays my own heritage. That term is a legacy of slavery in the US. In other parts of the world, it’s sometimes called canerow braids because sugar was the crop that slaves were working on, and in Yoruba (a Nigerian language) the various names have nothing to do with cash crops because that hair was just normal for women of all classes and not associated with field hands at all (Dabiri, 50).

Anyway, it is possible that the model for the Venus of Willendorf simply did not fit the stereotypical image of an Austrian woman. Hair texture is one of several markers of race. I’ll be returning to that idea several times throughout this episode.

Mesopotamian and Egyptian Hair

The earliest written records were more concerned with who owed taxes than they were with hair, but when literature gets going, we can glean a little more. For example, the epic of Gilgamesh, written between 2100 and 1200 BCE says that Enkidu, the wild man, had “a full head of hair like a woman” (Kovacs). The implication is that women had long hair, while men cut theirs shorter, which I wouldn’t have guessed for that far back. Partly I wouldn’t have guessed because there’s plenty of Mesopotamian art showing men with long hair, so I’m guessing fashions changed even then

In ancient Egypt both men and women often just shaved their heads. Wigs were common, but there are also artistic depictions of women without any hair at all. (Stern, chap 9, Fiell, 11). Baldness isn’t the only thing that startles the modern eye on some of these pictures, but I will be saving the subject of cranial modification for a future episode.

I have multiple sources that routinely refer to all of the Egyptian hair as wigs (Arnold, Fiele). I am not entirely sure how the authors know that none of it was the person’s actual hair, but that’s what it says. More on that in a bit. It is true that the British museum does own one genuine Egyptian wig of real human hair, beeswax, and resin dating from about 1500 to 1300 BCE. Their information on it says that it would have been worn by a high-status man (not woman), though once I again, I wonder how they know.

There are also ancient Egyptian paintings that show women with many braids (get picture from 13. 1), once again like cornrows, so the question of hair texture and what does it mean pops up once again.

There is a longstanding debate, with answers ranging from yes to no to maybe to occasionally to it’s-a-nonsensical-question-because-our-current-racial-categories-did-not-exist-then. And really what else can you expect when you ask about such a long-lasting culture from so long ago? As I mentioned in the Cleopatra episode, most ancient people didn’t bother to mention anyone’s skin color. It didn’t matter.

Roman Hair

By the time we get to Rome we’ve got written advice on hair. Ovid (43 BCE to 17 BCE) got a shout out last week for his blithe assurance that beautiful Roman girls didn’t have any of that distasteful leg hair, but he was fully in favor of Roman girls having hair on their heads. He says:

“Let not your hair be without arrangement; the hands applied to it both give beauty and deny it. The method, too, of adorning is not a single one; let each choose the one that is becoming it to her, and let her first consult her mirror. An oval face becomes a parting upon the unadorned head … Round features require a little knot to be left for them on the top of the head, so that the ears may be exposed. Let the hair of another be thrown over either shoulder. In such guise art thou … Let another leave her hair tied behind after the manner of well-girt Diana, as she is wont when she hunts the scared wild beasts. It becomes another to have her floating locks to flow loosely: another must be bound by fillets over her fastened tresses. Another it delights to be adorned with the figure of the tortoise of the Cyllenian God: let another keep up her curls that resemble the waves.”

-Ovid, Book the 3rd

Rome has left us few manuals on how to create all these styles, but they have left us the statues that show them in 3D and fair sprinkling of the physical tools. As in Egypt, most scholars refer to the hair styles as wigs. In part that’s because some of what we see on the statues appears improbable, especially without modern tools. On the other hand, scholars are generally not hairdressers. They don’t know what they are talking about.

To be clear, neither do I. But Janet Stephens is a hairdresser by day, and a historic researcher by night, and she has shown that yes, those elaborate hairstyles can be created on a living head of real and attached hair. The simple styles are done with bodkins: a single prong hairpin, much like a chopstick. One of my own sadly few hair skills is to put my hair into a bun using exactly the same principle. Archeology has turned up plenty of Roman bodkins.

But single-prong hairpins like bodkins limit just how elaborate you can go. Modern hairdressers use U-shaped bobby pins for the more gravity-defying looks, and Romans didn’t have those. But they did have tools that I never associated with hair dressing at all: your basic needle and thread. Stephens has demonstrated that if you are willing to actually sew the different sections of hair into place, then almost anything is possible, including lots of elaborate styles on Roman statues. It also explains some otherwise confusing passages in Roman literature. And it also means that the styles were sturdy enough to survive several nights of sleeping on them and yet more comfortable than many modern styles because there’s nothing hard or metal pressing against your head (Stephens).

High-status women would have trained servants to help them do this. Stephens assures me that it might be possible to sew up your own hair but taking it down would be something else again. Somebody’s got to clip those threads without clipping your hair. Probably not a do-it-yourself job. My guess is that your poorer women stuck with the bodkins. In Rome as well as everywhere else, complicated hair is a status symbol.

By Mark Landon, CC BY 4.0

There is also the question of color. Ovid amentions that a woman could dye her hair with herbs from Germany. He doesn’t specify the particular herbs, but another source suggests it was beechwood ash, which would lighten the hair. Basically it would make you blond (Fiell, 12). But just as now these things came and went out of fashion. A few hundred years later there are references that say respectable women had black hair. It was prostitutes who had yellow (Servius).

Medieval and Renaissance Hair

Your early medieval ladies covered their hair with veils, so there’s not much to say here. The size and shape of the headwear varied considerably over the centuries, but the hair underneath remained invisible or almost invisible.

It’s not until the 13 and 1400s that you start to suspect that women are actually removing their head hair. Petrarch, the early Italian Renaissance poet, wrote about his lady love’s beautiful forehead. (Petrarch, 299). Yep, of all her body parts, the one he thought to mention was her forehead, and it was supposed to be large. As in receding hairline large. There are paintings that show it: some women were removing the front inch or two of their hair to make their foreheads wider.

One of my sources suggested that there was a practical reason for the receding hair line and that was that the face makeup used by high-status women contained lead, which causes hair loss (Eldridge, 54). Maybe so, but the makeup stuck around for longer than the receding hairline fashion. The hair was getting more and more visible. Or at least a wig of false hair was more and more visible. Queen Elizabeth I of England used lead-based makeup and owned dozens of wigs, not because she was bald, but because they were fashionable and she could afford it. (Fiell, 33; Harvey). What’s interesting is that if you can pay for a lot of hair you didn’t grow, you can get pretty much whatever color you want. And she chose red.

Hair Before and After the Revolution

When we get to the 1700s, everything changes. The richest of the rich were rolling in wealth and their hair showed it. In France, it was now possible for men to make a good living as professional hairdresser for ladies (Fiell, 59). Previously, that wasn’t a profession. You just had your mother, sister, friend, or servant do it and hoped they were good.

Some of these hair dressers established academies and wrote books to train other hopefuls in the art. The most famous of these books was published in 1765 with 28 prints showing different hairstyles. Subsequent editions had even more (Legros). As far as I can tell, the manual did not give cute names to the styles, but an eager crowd of women most certainly did. The tête de mouton, or sheep’s head, was popular for a time (that’s soft curls all over the head) (Bashor, 11; Fiell, 59). Or there was the one Marie Antoinette popularized, with an equally descriptive name “the poof” (Fiell, 59; Bashor, 66).

But neither of these is the wildest of the ancien régime styles. That distinction belongs to La Belle Poule, which technically means the beautiful chicken. The hairstyle doesn’t include a chicken. Instead it contains a model battleship on top of masses of hair. It was created to commemorate the batter between the very real and lifesize French ship La Belle Poule and a British ship (Fiell, 607). This was hair as a patriotic act.

Some of these creations involved wigs or at least a little extra help to your natural hair and the elaborate concoctions were richly satirized in the press, including one cartoon where the hair dresser has climbed a ladder to reach the top of the seated lady’s hairdo, while his assistant inspects it with a sextant, the device sailors used to determine the angle between the sun and the horizon.

As you may have guessed, the Revolution ended this. From a hairdresser’s point of view, it was bad for business. Styles got significantly less elaborate.

Victorian Hair

The 19ᵗʰ century wasn’t as big on big gray wigs. But they were plenty happy to add hair pieces for extra volume, extra loops, buns, swirls or padding (Fiell, 92). Naturally you would try to get pieces as close to your natural hair color and texture, but wigs are expensive. The pretend-its-natural idea didn’t always work.

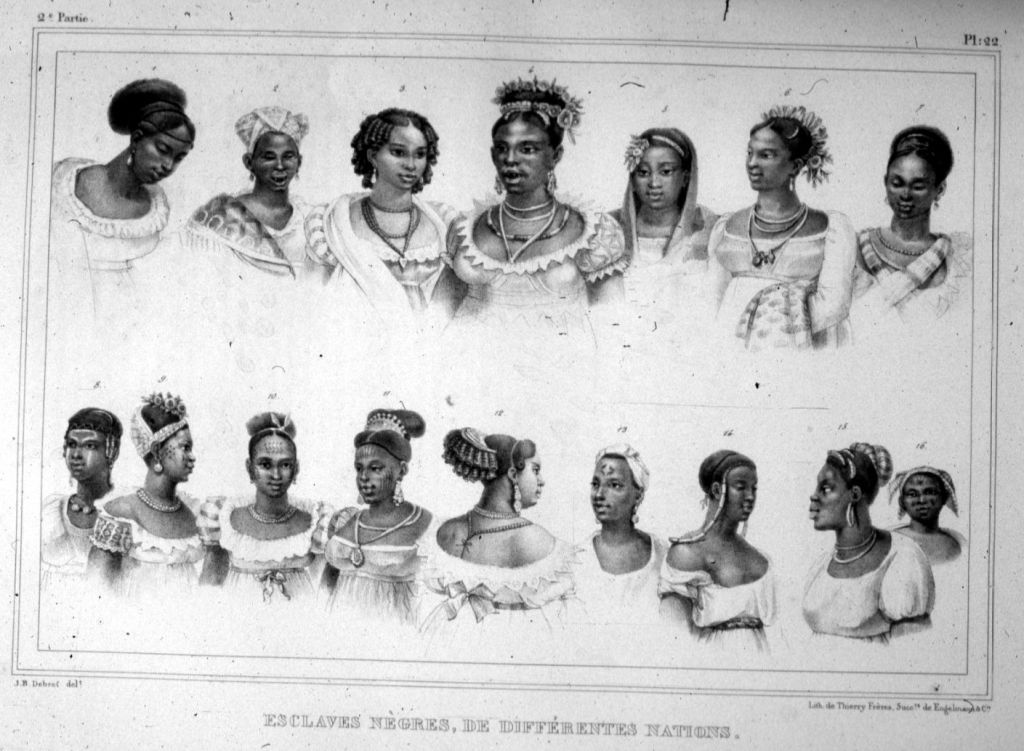

It especially didn’t work if your hair didn’t fall in line with the dominant culture. There’s very little on what enslaved women did with their hair when they had neither time nor products of their own. One former slave remembered that mothers would comb their daughters’ hair with the same metal-clawed cards that were used for carding sheep’s wool, but only on Sunday because there was no time on any other day of the week (Dabiri, 65-66).

The mothers themselves might not have had any hair. Cropping a female slaves’ hair short was done for various reasons, sometimes as a punishment and sometimes to make sure they looked ugly. Too ugly to tempt the white men. It wasn’t the men who decreed this, of course. It was the white women (Dabiri, 120-122).

Even when free, black women struggled in societies where Caucasian hair was beautiful. If they kept their African hair natural, they were ugly. If they tried to force their hair into European styles, they were pretentious and uppity (Dabiri, 104). Other ethnic groups also had different hair, but the reactions were different. Asian hair was often considered beautiful. And anyway it was easier to mold into European styles because the texture was not as different.

All my sources agree that the big hair event of the 19th century was in 1872 when Paris hairdresser Marcel Grateau invented the Marcel wave. It was a perm, using only thermal methods, not chemical ones, and it created a sensation.

From women’s point of view, it was gorgeous, and it lasted for weeks. From a professional hair dresser’s point of view, it was gorgeous and it couldn’t be done by your sister, friend or other unpaid amateur. You had to pay for it. Women flocked to the salon every few weeks, and handed over the money, a thing that had never happened on a mass scale before (Fiell, 98; Stenn, 124). Women’s salons were now big business.

20th Century Hair

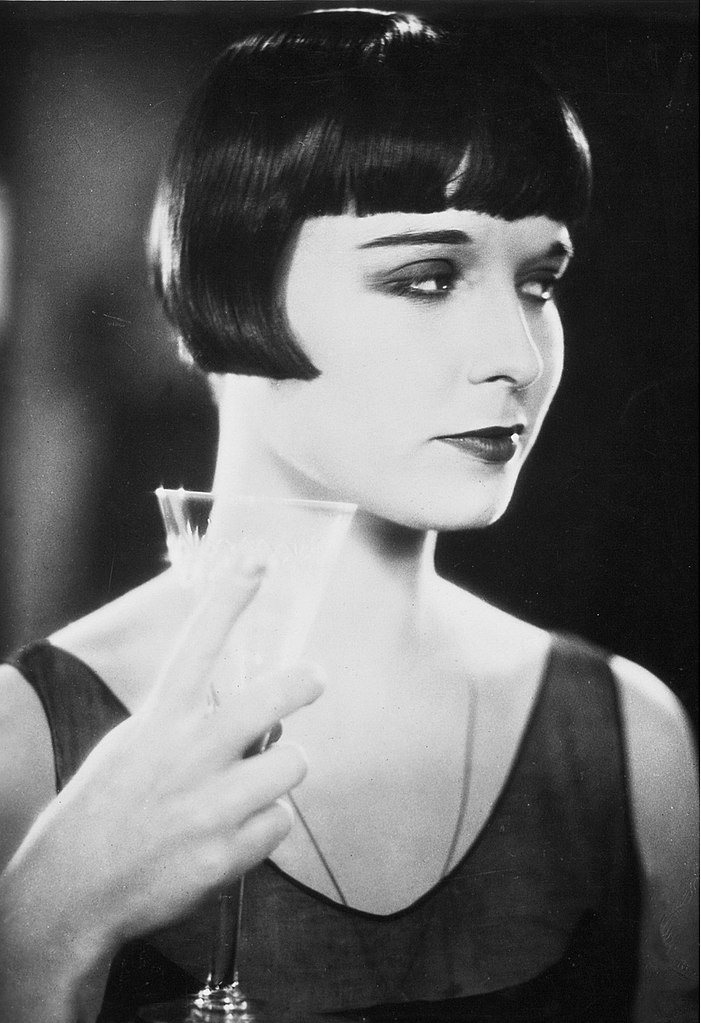

The hairdresser’s bottom line was later helped by the bob, a short haircut created in 1909. Up until this point no time period I looked at said women’s hair should be short. In fact, women were more often desperate to get more hair, not less. Men often sported long hair too. But the times they were a-changing, and in the 20s women flocked to the salons to get their hair smartly bobbed. The bob required skill. So you pay for it, and you pay for it on a regular basis.

(Wikimedia Commons)

Besides shorter, fashion was also going for less fussy. Working women were nothing new. Women have always worked. But in the past the working women were not driving the fashion trends. The fashions that got recorded, either in art or documents, were largely for upper class women, who had time and help. A growing number of middle class or aspiring to be middle class women had neither time nor help, but they did have spending cash.

And it’s a good thing they did because increasingly they also had models and actresses to imitate. The models and actresses were creating looks that required money, time, and help.

Case in point was Jean Harlow, the beauty icon of the 30s. Harlow was famous for her platinum blond curls, which she claimed were natural. Loads of people didn’t believe her. Sales of hydrogen peroxide skyrocketed as people bleached their hair. Then Jean died at age 26. People began to wonder if regular hair treatments had anything to do with it. Bleaching your hair became less popular. As far as I can tell, the cause of Jean’s illness is still not clear (Fiell, 231).

Considerably safer was the 1956 release of the first at-home one-step hair color commercial product. Women had been coloring their hair with henna, beechwood ash, and many other substances for millennia, but this was the first one sold down at your local shop in a box that you’d recognize today. It was enormously popular (Fiell, 271).

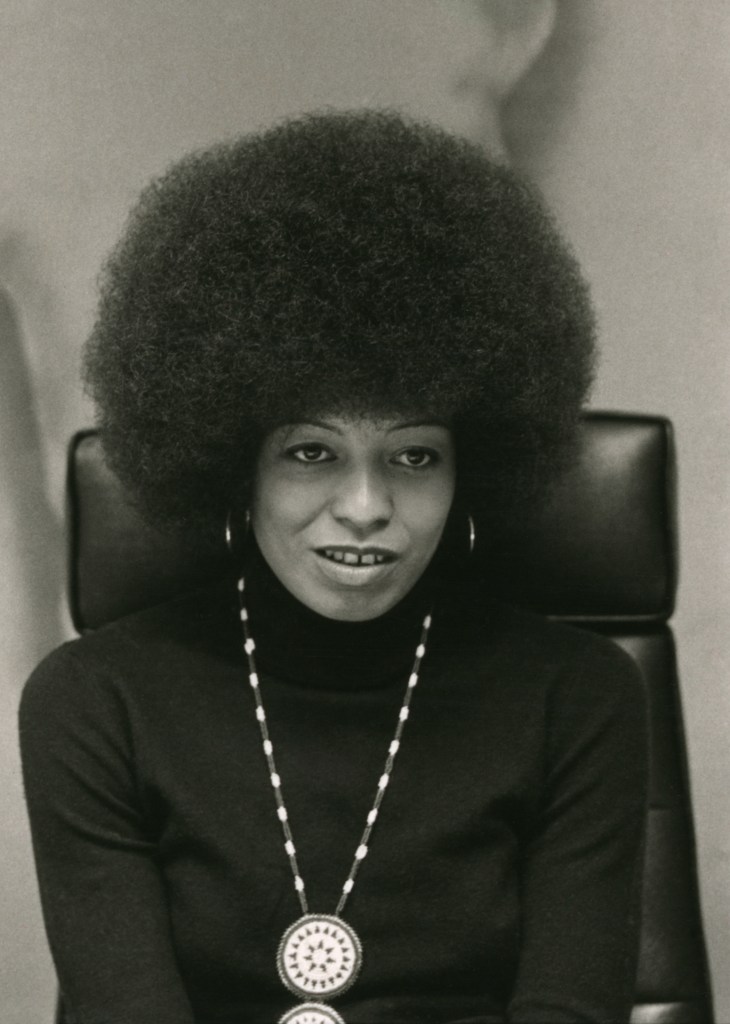

By the 60s, we were split, between those who were going back to fussy hairstyles and also those who were going for downright unkempt. But the far more interesting trend was that finally, finally, we get a public acknowledgement that some of these hairstyles are never going to work for a great many women.

Most of the styles I have mentioned so far assume that your hair grows down from your head. Not up. For many black women, that is just not the case. Theirs grows up. A great many black women did (and in many cases still do) go to an enormous amount of time, money, discomfort, and health risks to make their hair conform to standards that were created for women whose hair is entirely different. The 60s and 70s brought the black is beautiful movement and many women returning to styles that work well for the hair they actually had, but not always without negative feedback from schools, employers, and the general public. This continues to be a problem today.

(Wikimedia Commons)

In fact, hair is so tightly bound up with the question of race that some people have thought it to be a better marker of your race than skin color. This was infamously in the South African pencil test where you stuck a pencil in your hair. If it falls out, you’re white. If it stays in, you’re black. This is ridiculous on multiple levels. I tried it on my own hair, for example, and according to this test I am black. I can assure you that I fail every other test of blackness. Hair just comes in a range of textures, regardless of your race.

Anyway, styles got more elaborate again in the 80s, what with the oh-so-carefully crafted windswept look, among others, and then the 90s saw a rejection of overstyling in favor of hair that looked natural, which doesn’t mean that it necessarily was natural.

My sources continue on from there, but I will not because the closer I get to the present day the more my own hair insecurities come into play, so we’re going to call it good here.

Selected Sources

Arnold, Dorothea. The Royal Women of Amarna : Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1996.

Bashor, Will. Marie Antoinette’s Head. Rowman & Littlefield, 16 Oct. 2013.

Dabiri, Emma. Twisted : The Tangled History of Black Hair Culture. S.L., Harper Perennial, 2020.

Eldridge, Lisa. Face Paint : The Story of Makeup. New York, Abrams Image, 2015.

Harvey, Jacky Colliss. “How Elizabeth I Made Red Hair Fashionable – in 1558.” The Guardian, 8 Sept. 2015, http://www.theguardian.com/fashion/fashion-blog/2015/sep/08/how-elizabeth-i-made-red-hair-fashionable-in-1558.

Kovacs, Maureen Gallery, trans. “Epic of Gilgamesh.” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2012, uruk-warka.dk/Gilgamish/The%20Epic%20of%20Gilgamesh.pdf, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2030863. Accessed 11 Aug. 2024.

Legros de Rumigny. “L’Art de La Coëffure Des Dames Françoises, Avec Des Estampes, Où Sont Représentées Les Têtes Coeffées … Par Le Sieur Legros,…” Gallica, 2024, gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b86157476/f232.item, oai:bnf.fr:gallica/ark:/12148/btv1b86157476. Accessed 13 Aug. 2024.

Ovid. “Ars Amatoria; Or, the Art of Love Literally Translated into English Prose, with Copious Notes.” Gutenberg.org, 2014, http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/47677/pg47677-images.html. Accessed 12 Aug. 2024.

“Petrarch (1304–1374) – 53 Poems from the Canzonier.” Poetryintranslation.com, 2019, http://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Italian/Petrarch.php.

Schwarcz, Joe. “The Right Chemistry: How Jean Harlow Became a “Platinum Blond.”” Montrealgazette, Montreal Gazette, 16 Oct. 2020, montrealgazette.com/opinion/columnists/the-right-chemistry-how-jean-harlow-became-a-platinum-blond. Accessed 13 Aug. 2024.

Servius the Grammarian. “Maurus Servius Honoratus, Commentary on the Aeneid of Vergil, SERVII GRAMMATICI in VERGILII AENEIDOS LIBRVM QUARTVM COMMENTARIVS, Line 698.” Tufts.edu, 2024, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.02.0053:book=4:commline=698. Accessed 12 Aug. 2024.

Stenn, Kurt S. Hair – a Human History. Pegasus Books, 2017.

Stephens, Janet. “Ancient Roman Hairdressing: On (Hair)Pins and Needles.” Journal of Roman Archaeology, vol. 21, 2008, p. 110, http://www.academia.edu/31430226/_Ancient_Roman_hairdressing_on_hair_pins_and_needles_.

[…] I am skeptical of this last claim because I assume you are not taking this revolting mixture orally, but I quote it to point out that Pliny assumes it is women who want to dye their hair. There’s no mention of men doing so. Elsewhere he suggests ampelitis, an ingredient in pitch or asphalt, for the same purpose (Book 35, chap 56). Or bulbed leak (Book 20, chap 22). Wild orage (Book 19, chap 83), mulberries (book 23, chap 70), myrtleberries (book 23, chap 82), or gum acacia (Book 24, chap 67). The list goes on, most of them for dark hair, but occasionally for blond. Beechwood ash is also suggestion (Johnson, 88), which I mentioned last week. […]

LikeLike

I knew some of this, but once again, it’s the styles of the 1300s and 1400s that are the biggest shock to me because it’s so new. To me. A few weeks ago, the most-desirous-pear-shaped body and the apples-as-boobs were also the most new/shocking to me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] this episode on hair, this episode comes with a disclaimer: the history of makeup could be its own podcast, and I should […]

LikeLike

[…] in episode 13.6 on hair, I mentioned that some depictions of Egyptian princesses have them completely bald. But they are […]

LikeLike