I left off last week with makeup in Renaissance Europe, when women of all classes were smearing their forces with all kinds of creams and potions, some of them toxic, while men looked on disapprovingly.

Heavy disapproval did not change much. It is quite clear that upper class women continued to use makeup. For Marie Antoinette, putting on her daily range was ceremonial and witnessed by a great crowd (Hearsey, 22). She had more pomp and circumstance about the ritual than most women, but she wasn’t alone.

I do not know where Marie Antoinette got her rouge or what it was made of. But for the ordinary woman, an increasing number of books that would tell you how to make yourself a little makeup because you couldn’t yet get it at your local drugstore in a plastic container. Some books were specifically on cosmetics, like Abdeker or the Art of Preserving Beauty, published in 1754 and purporting to be translated from an Arabic manuscript. As per sadly usual, much emphasis is placed on having white skin, and yes, the author recommends lead (Le Camus, 81).

The one faint glimmer of change from the past 2000 years is that at least, the lead version is secondary. It gives first a recipe that it says are better. Not because it’s healthier, but because it is whiter (Le Camus, 81). Ho hum.

There is advice about rouge too and nothing could be easier than what the book suggests: take a scarlet ribbon, dip it in water, and rub on your cheeks (Le Camus, 82). This is how you can tell that clothes were not color fast yet. A laundry nightmare, but a blessing if you want cheap rouge.

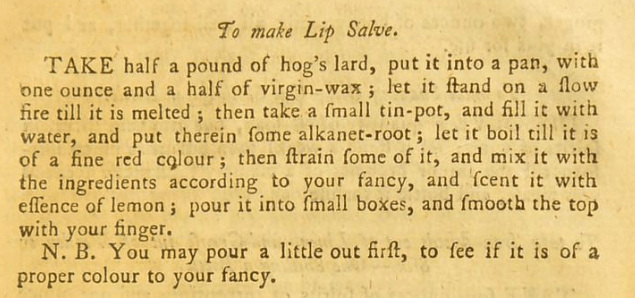

Many other books were published, not on cosmetics specifically, but on cooking. Guides for busy housewives generally saw no difference between whipping up a meal and whipping up a home remedy. And often they also saw no difference between a home remedy and a cosmetic. It all comes in the same book.

For example, Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, published in 1784, includes lip salve (which isn’t necessarily cosmetic) but she colors it red with alkanet-root, so it’s lipstick more or less.

She also has French rouge (Glasse, 401). The main ingredient is carmine, which was an ingredient only available through the Spanish crown. (American civilizations had known about it for millennia. It’s made from the dessicated bodies of an insect that lives as a parasite on cactus plants in Mexico and South America, but I doubt that women thought about that much while they smeared it on their cheeks.)

Anyway, women and their cosmetics were in for a rude reversal when we approach the 19ᵗʰ century. First there was the brief natural-is-beautiful movement, and then the French Revolution made the upper classes nervous of any visual display of excess. And then Queen Victoria said that makeup was vulgar and impolite (Eldridge, 33).

Victorian Cosmetics! How Crass!

Just like that Victoria accomplished what generations of moralistic men had not been able to do. Makeup use went down precipitously. There were Victorian women who thought nothing of squeezing their waist in a corset or strapping on a rubber bust, but they would not have dreamed of putting on lipstick or rouge (Riordan, 1). How crass!

The skin still needed to be white. That had not changed, but increasingly you accomplished it by protecting your skin with a parasol. Not by coating it in lead (Eldridge, 54). If you happened to have skin that wasn’t going to be alabaster white even if it didn’t see the sun, that was just your misfortune.

One of my sources claims cosmetics fell off because the health risks of things like lead were better understood (Jones, 62), but I think that’s nonsense. As I detailed last week, the health risks had been known for millennia. And I haven’t noticed women of my own era to noticeably prize health over beauty anyway. So I think it was Victoria and the culture that produced her that led to the decline in cosmetics.

It wasn’t just the Anglophone world who held that opinion. A German encyclopedia of the 1850s defined the word Cosmetics (Kosmetik) and went on to say that “no reasonable human being” should expect products like that to be “true beauty remedies.” Instead, you should focus on diet, exercise, and hygiene (Ramsbrock, 38).

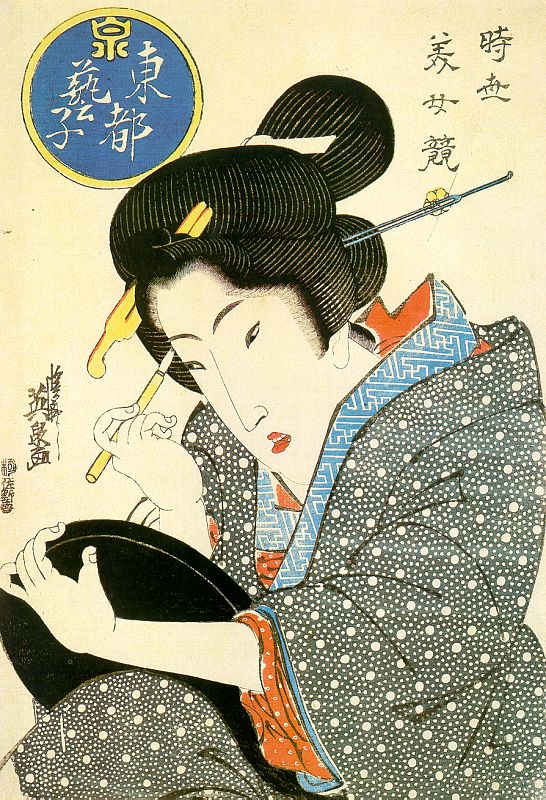

But this is not to say that no women were using makeup. Naturally, some women did it on the sly. Other women knew they were vulgar, and they were leaning into that. And still others lived in countries that neither knew nor cared what Queen Victoria thought.

(Wikimedia Commons)

The proof that not all beauty was natural—even in Victorian times—is in the marketing.

In earlier generations, I was able to quote recipes for making up your own cosmetics. But in the Industrial age, the recipes gradually tapered off and the advertisements ramped up.

Eugène Rimmel was primarily a perfume man. He supplied fragrances to many people, including Queen Victoria who apparently saw nothing morally wrong with scent. However, in 1860 he also invented the first factory-made mascara (Jones, 19; Eldridge, 159).

In the 1880s, Paris was opening the first department stores, and they sold color cosmetics (Jones, 64). German opera singer Ludwig Leichner invented new stage cosmetics in stick form (a thing not seen before). Though they were intended for actors (the very definition of vulgar), the non-actors of the world were eying them as well (Jones, Beauty Imagined, 637).

Overall, the number of women using these things was still small (or at least the number of women using them openly). But there was a reason for the rise in interest. When Victoria became queen, the camera had been invented, but it was not yet in common use. Most people had never seen a photo of themselves. Some people did not even have a mirror. Such would not be the case later in the century, and I’m sure you all know just how insecure you can feel after looking at a photo or a reflection of yourself. Victorian women felt that too (Riordan, 4).

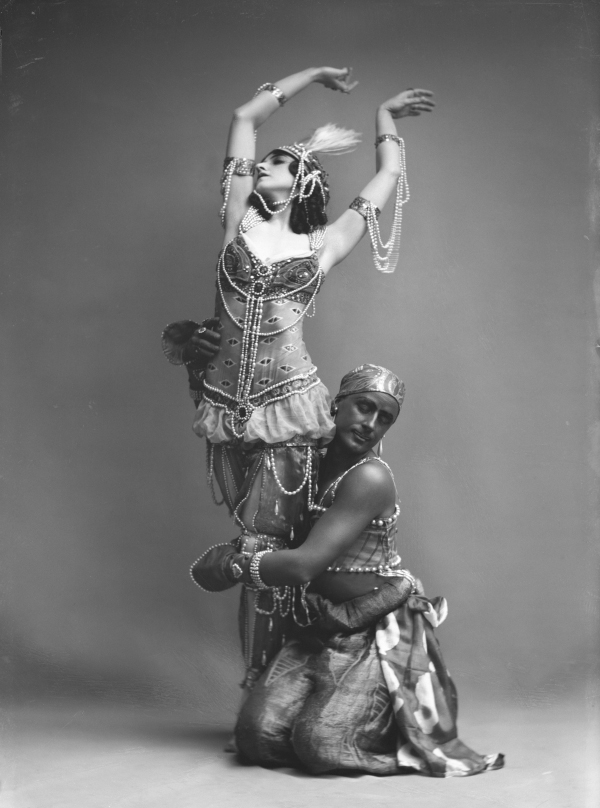

(Wikimedia Commons)

By the last quarter of the century, photograph was in full swing, and there was some cautious acceptance of a little makeup. Not too much now, but a little … if you were desperate … we guess it’s okay …

Instructions might still come draped in moral judgment. For example, in 1875 the women’s magazine Harper’s Bazaar published a book, not-so-charmingly called The Ugly-Girl Papers or Hints for the Toilet. (Toilet, by the way, still means your morning routine: getting washed, getting dressed, getting your hair done, getting your face done.)

The book says:

“Both from principle and preference, this book discountenances paint and powder. It believes that a woman needs no other cosmetics than fresh air, exercise, and pure water, which, if freely used, will impart a ruddier glow and more pearly tint to the face than all the rouge and lily-white in Christendom. But if she must resort to artificial beauty, let her be artistic about it and not lay on paint as one would furniture polish.”

(Dunning, 62)

After making you feel remarkably low for wanting such a thing, the book explains how to use powder and lists more benefits than I knew about. Then how to use rouge, how to make your own rouge (various ways), how to use eyeliner. Plus nail polish, hair powder, and lipstick (Dunning, 59-69).

That’s just in the one chapter. Other makeup suggestions are sprinkled through the rest of the 283 pages. One can’t help suspecting that the earlier moralizing was a virtuous façade. This author knows perfectly well that her audience wouldn’t have bought the book unless they were interested in this kind of thing. There is even a walnut stain for the skin. This is the first indication I ran across that anyone might want their skin darker, instead of whiter. However, it’s not as egalitarian as it sounds. The context is a little unclear, but I think the intended purpose is for your amateur theatricals at home. In other words, it’s blackface.

A Brave New Century

I don’t know what Victoria would have said about the Ugly-Girl Papers, but by the 20ᵗʰ century, women were ready for a full throttle embrace of these artificial aids.

And the so-called vulgar women played a role. In 1910, the Ballet Russes premiered Scheherazade at the Opera Garnier in Paris. It was exotic, it was sultry, it was a huge hit, and sales of mascara and eyeliner skyrocketed as women tried to imitate what they had seen on stage (Riordan, 7).

They were wearing it openly too. It was a time of innovation and breaking past taboos. Lipstick was first sold in tubes around 1915 (Riordan, 37, Jones, 102).

By World War I, the tables were turned on respectability. A 1916 ad for skin care products asked women “Is yours a ‘war’ face? Even if your social or professional life does not demand it, your patriotism demands that you keep your face bright and attractive” (Eldridge, 100). Cosmetics themselves were flying off the shelves. It was your patriotic duty to wear them.

When the war was over, ads got even more personal and aggressive. “Would your husband marry you again?” asked one. (Eldridge, 105). Maybe not, and that’s why you should buy insert-product-of-your-choice. It would be decades before advertisers backed off from such tactics.

By 1930, American women had 3,000 different face powders and several hundred rouges on the market (Jones, 102). Actresses continued to play a big role in cosmetics, but somehow actresses had ceased to be vulgar. They were now ideals to emulate, not trashy women to look down on.

The Depression did not dampen the desire for cosmetics. On the contrary, cosmetics were a luxury that was still more or less achievable (Riordan, 17-18). Compared with many other things, they were pretty cheap.

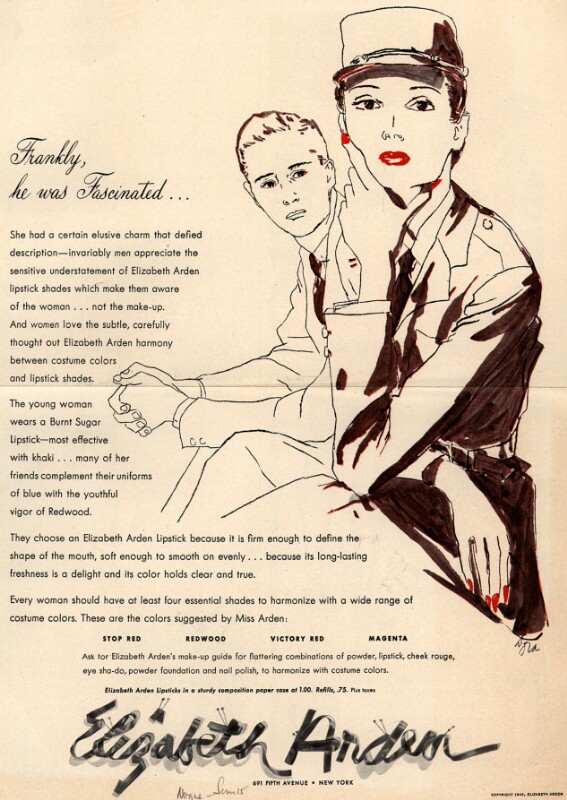

By World War II, not only were cosmetics acceptable, they were practically required. Women in the US Marine Corps were issued makeup kits with their uniforms. The kit included rouge and nail polish and lipstick in Montezuma Red, a shade created by cosmetic giant Elizabeth Arden. Female marines were required to wear it, but also to take no more than two minutes putting it on (Natl Museum of the Marine Corps).

Women in other uniforms weren’t quite so regulated, but the world was nonetheless clear and open about what they were doing. British newspapers were full of suggestions about which shades of lipstick, rouge, and powder looked best against a khaki uniform versus a blue one (Staveley-Wadham). You certainly don’t want to get your shades wrong.

Still, it was a tricky thing to navigate because too much was as bad as too little. One army official told a reporter that “We are not discouraging the use of make-up. In fact, we prefer our women to be pretty rather than pasty-faced. But we don’t like them to look like paint pots” (Liverpool Daily Post Friday, 26 March 1943, “War” page 2).

For women on the home front, things were much the same. Rosie the Riveter wore makeup. Multiple governments claimed makeup was necessary for morale, and therefore cosmetics were kept in production even when many other goods were scarce.

By 1948, 90% of American women used lipstick and 73% used rouge (Jones, Blonde, 129). The rates were lower outside of the US, but that was largely a question of disposable income and an American value system, which “had turned beauty products into a ‘necessity’ rather than a luxury’”. The rest of the world was going to recover from the war and as they did, their women spent more money on beauty products too (Jones, “Blonde,” 132-133).

Elizbeth Arden was still going strong, as was her competitor, Helena Rubinstein. By the 1960s, Helena Rubinstein’s cosmetics were on the market in over 70 countries (Jones, “Blonde”, 140). French companies like L’Oreal and German companies like Beiersdorf had extensive international businesses too. There were a host of other players from many countries.

The industry was helped along by continuous innovation. In 1958 Helena Rubinstein had sold the first mascara that came with an applicator wand (Riordan, 28). Foundations and powders finally expanded their color range out of white and more white. This was partly to recognize that not everyone is descended from northern Europeans. But it also reflected a reversal of the trend that had been in place for millennia now: even those of us who are pasty-white no longer wanted to be (Eldridge, 184). Tanning was in. More about that in a future episode, I hope.

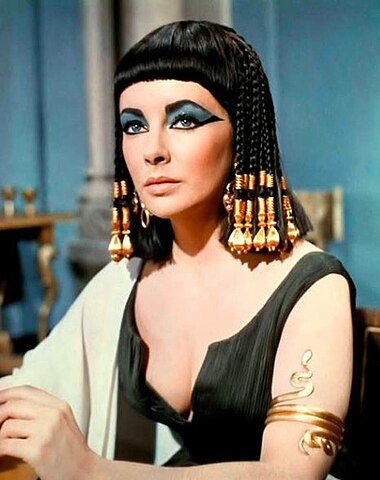

Eye shadow had been around since Elizabeth Arden first sold it in 1914. But it didn’t really take off until 1962, when Elizabeth Taylor wore an enormous amount of blue eye shadow as Cleopatra. The look wasn’t particularly historical from an Egyptologist’s point of view, but fans didn’t care. Eye shadow became essential (Riordan, 168. Eldridge 64, 169).

(Wikimedia Commons)

As for lipstick, you will want to go to Patreon or Into History where I will be releasing a bonus episode called Hazel Bishop and the lipstick that stays on you, not on him.

Cosmetics in the Late 20th Century

In the intervening decades, makeup trends came and makeup trends went, but makeup itself was firmly entrenched. And how women did or did not wear it still invited judgment. From men, from other women, from school administrators, from prospective employers, from current employers, the list goes on. It was a trap for women. Because wearing too little was a problem, and so was wearing too much.

In the 1980s, NASA’s first female astronaut Sally Ride was irritated about makeup. Everyone from the press to the engineers wanted to talk to her about what makeup she would take into space, when all she wanted to focus on was the job. It seemed to her to be sexism in action: focusing on her status as a woman, rather than her status as an astronaut.

But many of her female colleagues and successors felt differently. They wanted NASA’s makeup kits because knew that their pictures as astronauts would be distributed around the globe, and that “expectations for women’s appearances [don’t] go away even when women [leave] the planet. The first women in the US to train for spaceflight faced immense pressure from the media … and from NASA, which in part depended on public perception to get funding. Reasons to wear or not wear makeup all had consequences, and each astronaut had to decide which to bear—something the male astronauts, who were automatically assumed to be professional without makeup, didn’t have to consider” (Nudson, 27-29).

Selected Sources

Dunning, Susan C. The Ugly-Girl Papers. Harper’s Bazar, 1874, dn790005.ca.archive.org/0/items/uglygirlpapersor00powerich/uglygirlpapersor00powerich.pdf. Accessed 3 Sept. 2024.

Glasse, Hannah. The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy. 1784, archive.org/details/b21527350/page/400/mode/2up?ref=ol. Accessed 2 Sept. 2024.

Hearsey, John E N. Marie Antoinette,. Sphere Books, 1972.

Jones, Geoffrey. Beauty Imagined : A History of the Global Beauty Industry. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2012.

Jones, Geoffrey. “Blonde and Blue-Eyed? Globalizing Beauty, c.1945-c.1980.” The Economic History Review 61, no. 1 (2008): 125–54. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40057559.

Le Camus, Antoine . Abdeker, Or, the Art of Preserving Beauty. 1754, books.googleusercontent.com/books/content?req=AKW5Qad-atEEZZE0odSRh6n8N7kPxJCsmgp0fLY9HgzQFcb8E-BxoA5LxIPKPqsfiU_g2yFHSc4Lrn06DBhxGCKLS9wovbLZPpjf6fPWYNtPHxbcB4OBeLYNsXAIuNRsdikpInSay_meW8YPS45atdrsJAAfI68MQyEJMRFLv2FXTYeqIy6O2bKLX2kOEehtj9mkQ-6PuSfjIjdoYHDV8xfswRfqR4H1GL-6Z5-KiUrO3VzX1MAgUcTWGk0uyOVxWvJcpXCG20MJIz8fe5LcGinue-034DVmfQ. Accessed 2 Sept. 2024.

National Museum of the Marine Corps. “Montezuma Red” -Women Marines in WWII. https://www.usmcmuseum.com/uploads/6/0/3/6/60364049/montezuma_red.pdf.

Neiderriter, Adrienne. “Speak Softly and Carry a Lipstick”: Government Influence on Female …” Yumpu.com, 2009, http://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/11635094/speak-softly-and-carry-a-lipstick-government-influence-on-female-.

Nudson, Rae. All Made Up. Beacon Press, 13 July 2021.

Ramsbrock, Annelie. The Science of Beauty Culture and Cosmetics in Modern Germany, 1750-1930. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Staveley-Wadham, Rose. ““Make-Do Make-Up” – Makeup during the Second World War.” Blog.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk, 21 Sept. 2020, blog.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/2020/09/21/makeup-during-the-second-world-war/.

“War.” Liverpool Daily Post, 26 Mar. 1943, p. 2, http://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000650/19430326/039/0002. Accessed 4 Sept. 2024.