Religiously speaking, the woman behind the man behind Christmas is definitely Mary, and I’ve already done two episodes on the Historical Mary. Check out episodes 5.1 and 5.2, plus a bonus episode available on Patreon. The big man behind the secular side of the holiday is Santa Claus, and today’s special episode is the history of the woman behind him. Consider it a sneak preview of the upcoming series: The Woman Behind the Man.

For a very long time, Santa was a single man. This was true when his name was Nicholas, and he was a bishop in 4ᵗʰ century Turkey. He was famous for giving gifts to the poor and especially for having given dowries to three poor sisters who would otherwise have been forced into prostitution. There are a load of other tales about Nicholas’s good works, and he became the patron saint of children, sailors, merchants, archers, repentant thieves, brewers, pawnbrokers, unmarried people, and Russia.

St. Nick was very popular through the medieval period and into the early modern period. His feast day, December 6th, was a day for secret gift-giving, though that is far from the only way that he was venerated, especially in the Eastern Orthodox tradition. The customs and his importance varied from region to region, but as far as I can tell, he was always a single man.

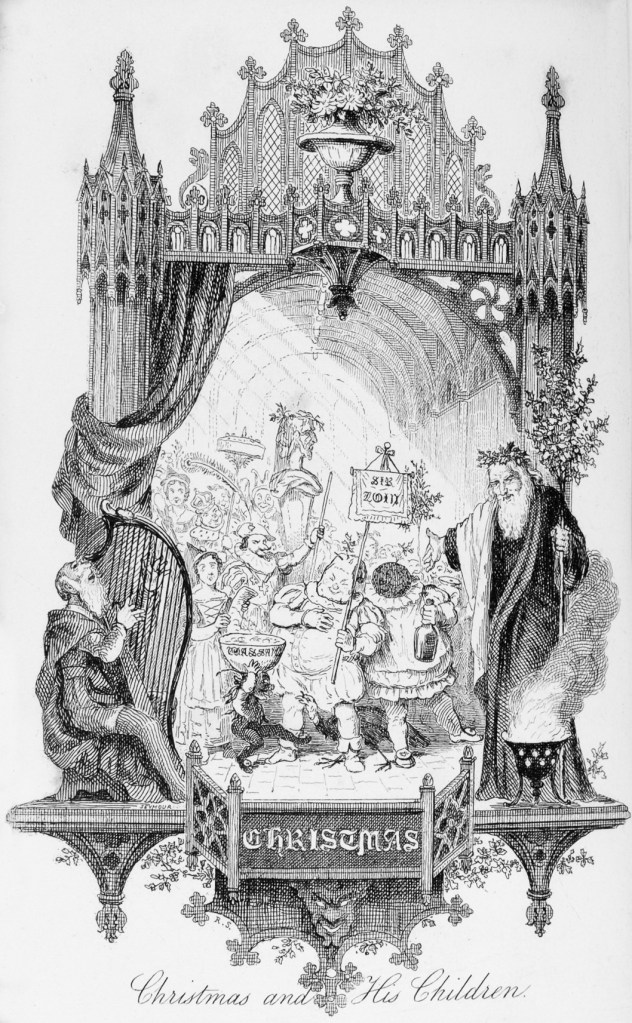

(Wikimedia Commons)

Over in England, Santa was showing his naughtier side. Yule was the pagan mid-winter festival, connected with the Wild Hunt and the God Odin. When England was Christianized, the name became Christmas, but the old traditions were still alive and well. The city of York, for example, had an annual parade called the Riding of Yule and His Wife. (Look at that! Mrs. Claus’s first appearance!)

In the parade, Yule carried a shoulder of lamb and a large cake of fine bread. His wife carried a distaff, which is a spindle. It’s used for spinning fibers into thread. Or in other words, he carried the reward of hard labor. She carried the tools of hard labor. I could make a few salty comments here, but I don’t need to because later depictions of Mrs. Claus are going to do it for me. Hold that thought.

The attendants in the parade threw nuts at the adoring crowd. All this may not sound particularly naughty, except that the reason we know about it this was because the church was down on it. As late as 1572, The Archbishop of York lost patience. He ordered the Yule parade forbidden because it drew “great concourses of people” away from church going (Dictionary of English Folklore). Which is a criticism Santa and his version of Christmas still get today.

In all fairness, Yule celebrations did have a reputation for being “unruly.” Let’s just say that the joy of children and family togetherness was not the overriding message of the celebration.

Anyway, having been banished from York, our heroine Mrs. Claus goes back into hiding for several hundred years.

By the 18ᵗʰ century St Nick was so popular in the Netherlands, his name was contracted down from Sint Nikolaas to Sinterklaas. That is the name that Dutch immigrants brought when they moved to New Amsterdam, better known to you as New York City.

Their English-speaking neighbors couldn’t pronounce the name, but they knew a good idea when they heard one. They adopted him as Santa Claus, but his wife went entirely unmentioned. From the New World, Santa then traveled back to England where he merged with Father Christmas, which was the new and politically correct name for Old Yule.

(Wikimedia Commons)

The 19th Century, Christmas, and Womanhood

The 19ᵗʰ century would bring change on multiple fronts. For one thing Christmas got bigger. Bestselling authors like Washington Irving and Charles Dickens wrote stories that elevated minor, local customs into major, pan-continental symbols of peace on earth and good will toward men.

No longer was Christmas just an excuse for adults to gather down at the pub. Increasingly, it was a time for families and neighbors to gather with special food, special decorating, pressure to buy the perfect gift, etc., etc., etc.

At the same time, the role of women was shifting. Longtime listeners of the show may remember episode 7.10 Industrialization Hits the Housewife, where I talked about women in 19th century censuses. At the beginning of the century, individuals didn’t have professions. The family had a profession. The man’s name may have been the one on the door, but he, his wife, and his children were collectively butchers. Or bakers. Or candlestick makers. Or whatever.

By the middle of the 19ᵗʰ century, middle-class individuals had professions. The man might be a banker or a businessman. His wife’s profession was housewife. And by the end of the century that same housewife was listed as having no profession. She was a financial dependent with the exact same status as her children. To this day, women who stay home with their kids are frequently described as women who “don’t work.” Which is obviously untrue and unhelpful, but not the point of today’s episode.

For 19th century women, there were a variety of possible responses to this long, slow demotion in status. One common response was to double down and turn it into a virtue.

The Cult of True Womanhood (also called the cult of domesticity) was an ideology that told women their place was in the home. Not just because they were too weak to survive in a man’s world, but also because only their feminine touch could make home the heaven it should be. It was very, very, very, very important for women to be at home, making sure the house was clean, the food was good, the children were well-behaved, and the wife herself was sweet, gentle, pious, and submissive. Only if she accomplished all that could her man and her children, not to mention society at large, function properly. Women might not have a paycheck to prove their value, but women in the home played an absolutely vital role nonetheless.

Upper and middle-class wives, I mean. No one denied that poor women were going to work. Of course, they would work. But those women largely couldn’t afford to celebrate Christmas anyway.

And I am getting back to the holiday, because Christmas, as explained by Dickens and others, is a home-centered holiday. Who was going to cook the big meals? Wrap the presents? Decorate the house? Clean up before guests arrive and again after guests leave? Certainly not the man of the house. That didn’t fall in his sphere at all.

Christmas in the 19ᵗʰ century was primarily a woman’s job. Men enjoyed it, but women made it happen. And a whole host of newly literate women were eager for ideas and tips. In a pre-Pinterest world that meant magazines, which functioned just like mommy blogs and social media influencers have more recently. In the words of one of my sources “In the 19ᵗʰ century, Washington Irving and Charles Dickens told the nation what Christmas meant; Godey’s [Lady’s Book] and Harpers [Bazar] showed how to make it so” (Marling, 135).

Mrs. Claus Reappears

Magazines also published fiction that added to the Christmas lore and here at last is where Mrs. Claus finally shows her face again. Because by the mid-to-late 19ᵗʰ century, it was utterly ridiculous to think that Santa, being masculine, could possibly be pulling Christmas off on his own. Who could believe anything that far-fetched? There was, quite surely, a woman at the North Pole, keeping the Santa suit laundered, the treats cooked, the presents wrapped, and the toy-making elves focused on their tasks. A man might be good at hitching up reindeer, driving a sleigh, and slipping up and down chimneys, but this other stuff required a woman’s touch.

It is not just one writer who showed us Mrs. Claus, but many. A long series of literary hacks published poems and stories across the 1870s and 1880s. Most of these writers were women themselves. They probably had some experience with how Christmas actually functions.

Like Enna Beach, who in 1870 published a poem about a discouraged Santa who thinks Christmas will be ruined because the price of sugar is so high, and Dasher and Prancer are lame. But his dear wife Joan steps in to encourage him, for she can charm the reindeer’s hurts away and her fairy god mother left her a purse that is always full of gold, so “though sugar is high, my good old man, here’s plenty of gold to buy it and so, As we have no children, the better we can give to others, the more, you know.” It’s a very sweet tale.

Four years later in a story by Georgia Grey, both Clauses were considerably snippier, and Mrs. Claus takes an unexpectedly feminist stance. In Santa returns to the house briefly on Christmas Eve because he forgot something. And I quote:

“Must you go out again?” inquired his wife, bringing him the desired article.

“Go out again?” echoed Mr. Santa Claus, rather indignantly. “How simple-minded you are. It seems to me, madam, that you have very little idea of my laborious duties. But of course, you, being a woman, can’t understand anything about the hardships I have to endure.” He sighed, and tried very hard to look like a martyr, as he undoubtedly considered himself just at that moment; but the effect seemed entirely lost upon his good wife.

“I’m very sure I know what labor means,” she replied. “I work like a slave all the year to prepare the presents you are so fond of scattering at Christmas; and I only wish I could have the privilege of sharing your toils then. But I suppose no one ever expects to see Mrs. Santa Claus.”

“No one knows of your existence, even,” said her husband. ‘‘You know there isn’t room for two of us in my sleigh, when it’s loaded down with everything under the sun; so, what is the use of talking? I am not a woman’s rights man; I consider that your proper sphere is at home. You are an excellent person-in your place, however, my dear. Will you bring me a pillow, my love?”

You can probably guess what happens next. Of course she takes his place in the sleigh, and of course she’s entirely successful. At the end of the story,

Then Mr. Santa Claus had a lecture; and it must have been a very severe one, too, for before its close he meekly ‘lopped his ears,’ and said, ‘‘yes” to everything she required.

Chalk one up for Mrs. Claus there, as presented by writer Georgia Grey.

However, Mrs. Claus as raging feminist did not always turn out well. The Godey’s Ladies Book was happy to tell women how to dress, how to decorate, and how to raise their children, but they were not a women’s rights publication, dear me, no. In 1879, they published a story by M.B. Horton. This writer used initials, so we don’t get to know if this is a man or woman writing.

M.B. Horton’s story featured a Mrs. Claus who snuck out of the North pole while her husband was sleeping, so she could deliver some gifts herself. The opening paragraphs include a crack about her appearance, which had “no trace of finery about the garment which would indicate a weak woman’s regard for fashion, only a distinguished and severe ‘a la Rights mode’.”

She then declares to a family, including the children, that

“For about 1800 years that rotund tramp, St. Nicholas, has been enjoying himself hugely on Christmas Eves by wandering here and there with his reindeer and his gifts, making himself greatly popular with both young and old.

“ Allow me to say that it is quite high time that Mrs. St. Nicholas should be allowed some privileges! and if she is not allowed, she will take them!” (Her appearance here was really majestic.) …

“I appear before you,” she continued, in a softer tone, “as a most injured and long-patient woman, now claiming your sympathy for her wrongs. If the old and young Santa Claus could tell their tale, they would give centuries of detail concerning stockings darned, shoe-strings continually tied up, and buttons sewed on, while Mr. St. Nicholas was being petted and praised for his charming liberality at the Christmas holidays—1800 years of dull home life for the one, and a merry tramping all over the world for the other! …

“Yes, for 1800 years and odd, I have been left at home to pine and drudge. 1800 years and odd! A good long time indeed, for a woman to mind her husband’s p’s and q’s; and I have determined not to stand it after 1878.”

I am reminded that even way back when Mrs. Claus was the wife of Yule, he carried the feast, and she carried the tools of more work. Her grievances had been building for a very long time.

However author M.B. Horton does not appear to think her cause was just. On the contrary. The gifts she gives are all wrong. Exactly what each family member does not want and cannot use. This is not Mrs. Claus’s mistake. It’s a trap laid by Santa to cure her of her longing for equal rights by ensuring that the package she took was full of ugly, broken gifts. Then when everyone is in tears, he shows up with the real bundle of gifts and the family is happy. So Christmas is saved (but not by her). Mrs. Claus who now realizes that forgiveness is what she does best, and all is well for the devoted wife.

Forgive me if I find this Christmas story a little less than heart-warming.

Not all the tales were so blatantly political, but many were eager to put Mrs. Claus in a pivotal role. Like the 1880 story, where Santa forgets twelve dolls, and Mrs. Claus puts a side saddle on Blitzen and rides out after him. Santa is pleased with her help in this case.

Or the 1881 poem by Margaret Eytinge, which features a Mrs. Claus who supervises the elves. The 1885 poem by Edith Thomas makes it clear that a single Santa was ridiculous—he needed a wife to tell him which gifts the children would like.

The element of female exhaustion wasn’t gone. In 1884 Sarah J. Burke wrote a feisty poem called “Mrs. Santa Claus Asserts Herself”. It includes the lines:

Now I’ve nothing to say in a slanderous way

Of the man I have promised to love and obey:

He’s a jolly old soul, he acts up to his role,

And as husbands go, he may pass, on the whole.

…

With a nod and a blink he would lead you to think

He had dressed all the dolls ere a weasel could wink;

No; while he’s in bed—to his shame be it said—

It is I who am plying the needle and thread.

And this in a magazine for children?

In 1892, a properly grateful Santa thanks his wife for all the doll clothes she sews in a poem by Ada Shelton.

Thus far, I suspect you have not recognized the name of a single one of these writers. They collectively gave us a character we all know, but none of them achieved fame and glory for it. The only one you might have heard of is Katharine Lee Bates, who also wrote the words to “America, the Beautiful.” But before that she wrote a poem about a Mrs. Claus who begged her husband to take her with him for “Why should you have all the glory of the joyous Christmas story, and poor little Goody Santa Claus have nothing but the work?”

Overall the general sense you get from these stories is the Mrs. Claus works very hard for little appreciation. That was a feeling so many women could relate to. In 1902, a magazine gave her pretty much all the credit for the Christmas seasons:

We will … take it for granted that there is a Mrs. Santa Claus, a baby Santa Claus, and as many as seven or eight other young Santa Clauses of various ages and sizes. This being granted, it must follow as naturally as day follows night, that Mrs. Santa Claus takes a warm and lively interest in the benevolent business of her excellent husband, as all good wives do; and should Santa Claus’s biography ever be written up, and the whole truth come out concerning his domestic relations, we would not be surprised if it should appear that it was Mrs. Santa Claus who first “set him up” to the whole reindeer-sleigh, stocking-filling, chimney-descending, joy-bringing trade ; who selected his gifts for him at some polar department store, packed ‘em up for transportation, and told him just where to go first and “not forget.” That’s the way it is with most men who do any good in this world. Their wives seldom get the credit for it until they die and some one publishes the family diary.

–Anonymous in Frank Leslie’s Weekly “Concerning Mrs. Claus”

Mrs. Claus in a Brave New Century

In the early 20ᵗʰ century, Mrs. Claus doesn’t put in so many appearances. Maybe because women felt they were getting somewhere. New century, new rights, and all that. Maybe? But she never really completely disappears.

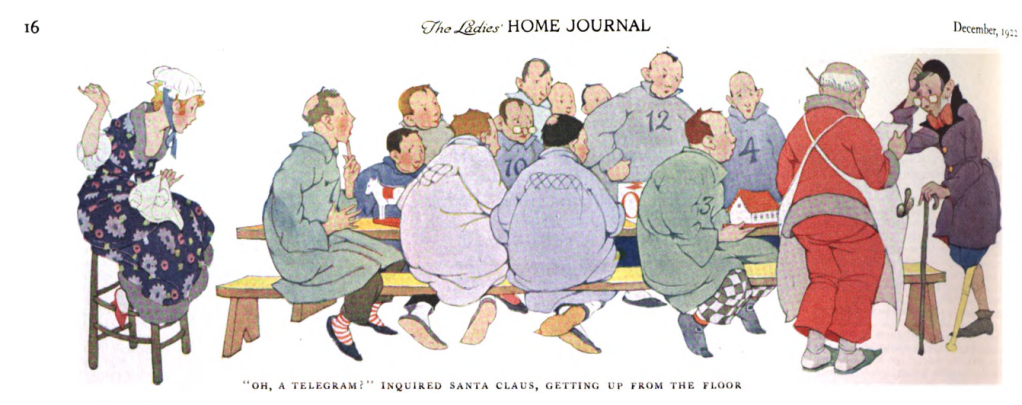

For example, there’s a 1922 story where Mrs. Claus has to solve a crisis in the North Pole because a child has asked for a red-headed doll, something no child has ever wanted before. Red-headed dolls aren’t on the production line! But Mrs. Claus manages somehow. Also Santa broke his leg and Mrs. Claus had to be talked into filling in (Addington).

She picks up visibility again in the mid-century with novels and children’s books and the silver screen.

As far as I can tell, Mrs. Claus made her film debut in 1964 in the film Santa Claus Conquers the Martians. Yes, it’s a sci-fi film and I did not see that coming, did you? You can check it out on this link. Fair warning though: it makes a lot of lists for Worst Movies Ever.

One month after that movie was released, Mrs. Claus had a brief appearance in the far more popular stop-motion television special Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer. It is still played on TV, every Christmas season. In 1970, in the stop motion Santa Claus Is Comin’ to Town, she got a bigger role. She’s young, as his the handsome Kris Kringle, and to my delight, they both have red hair.

Since then Mrs. Claus has appeared every year or two in a new film, book, song, or other creative endeavor. But the hands-down best portrayal of her ever is the 2016 Marks and Spencer advertisement in which Mrs. Claus fulfills a last-minute Christmas request that Santa cannot cope with. It’s a familiar story that has been told at least since Georgia Grey’s 1874 story, but now with a modern twist because Mrs. Clause doesn’t side-saddle Blitzen, which is terribly old school. No, she dresses fit to kill and pilots her own helicopter.

The Telegraph review of it said Mrs. Claus had always been a downtrodden character before, doing nothing but wave Father Christmas goodbye. Which goes to show that Telegraph writers don’t necessarily know their history. Mrs. Claus had saved Christmas many times over, as you now know. But I will agree whole-heartedy with the Telegraph writer that

At a time of year when all around seem to be telling women how to drop a dress size before party season; which shop the best mums go to; or how to plan ahead to ensure everyone else’s needs are satisfied on the big day, it’s refreshing to see a middle-aged woman tearing through the skies in a helicopter as if it’s the most natural thing in the world.

If you haven’t seen the ad, check it out here. If you have seen it, go see it again. If ever an ad was worthy of being watched on repeat, this is the one.

My sources today are mostly the unsung heroes behind Mrs. Claus. These are Enna Beach, Georgia Gray, Sarah Addington, Katherine Lee Bates, Sarah J. Burke, Margaret Eytinge, MB Horton, Lucy Larcom, Bell Elliott Palmer, Edith M. Thomas, Anonymous, Anonymous, and Anonymous. These women (and maybe possibly a few ) are mostly forgotten, but they captured a character that is now instantly recognizable, though we still haven’t settled on what her first name is. I have a special thank you today to Teresa and Lisa who both made one-time donations. Fabulous people like Teresa and Lisa help keep the women’s history still coming. If you are able to be like them, please see the side panel for various ways to do so. My compliments of the season to all you lovely listeners. I hope you feel joy, rather than exhaustion, and get the gratitude you deserve. Next week is another off week for the podcast, but stay tuned in 2 weeks for the real beginning of Series 14, the Woman Behind the Man.

Selected Sources

Addington, Sarah. “The Great Adventure of Mrs. Santa Claus.” Ladies’ Home Journal, Dec. 1922, pp. 16–60, http://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Ladies_Home_Journal/5LAaAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0. Accessed 10 Nov. 2024.

Anonymous. “Complicating Christmas.” Ladies’ Home Journal, Dec. 1899, p. 20, hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015012341650?urlappend=%3Bseq=20%3Bownerid=109669301-19. Accessed 10 Nov. 2024.

—. “Concerning Mrs Santa Claus.” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly, vol. 95, no. 2468, 25 Dec. 1902, p. 716, archive.org/details/sim_leslies-weekly_1902-12-25_95_2468/page/716/mode/2up?view=theater. Accessed 10 Nov. 2024.

—. “Mrs. Santa Claus’ Christmas Eve.” The Connecticut Churchman, vol. 41, 3 Jan. 1880, p. 26, books.google.com/books?id=gCDnAAAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=the%20churchman%20Mrs%20Santa%20Claus’s%20Christmas%20Eve&pg=PA26#v=onepage&q&f=false. Accessed 10 Nov. 2024.

Marling, Karal Ann. “The Revenge of Mrs. Santa Claus or Martha Stewart Does Christmas.” American Studies 42, no. 2 (2001): 133–38. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40643258.

Bates, Katharine Lee. “Goody Santa Claus on a Sleigh Ride.” Wide Awake, vol. 28, no. 1, Dec. 1888, http://www.google.com/books/edition/_/I5dFAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1. Accessed 10 Nov. 2024.

Beach, Enna. “Santa Claus and Joan.” Wood’s Household Magazine, vol. 7, no. 40, Dec. 1870, pp. 270–271, http://www.google.com/books/edition/Wood_s_Household_Magazine/92bMIJxd1kkC?hl=en&gbpv=0. Accessed 10 Nov. 2024.

Burke, Sarah J. Mrs Santa Claus Asserts Herself. 1 Jan. 1884, p. 132, books.google.com/books?id=4KivdYHq200C&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=sarah%20j%20burke%20mrs%20santa%20claus%20asserts%20herself&pg=PA132#v=onepage&q&f=true. Accessed 10 Nov. 2024.

Eytinge, Margaret. “Mistress Santa Claus.” Harper’s Young People, 20 Dec. 1881, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/50545/50545-h/50545-h.htm. Accessed 31 Oct. 2024.

Grey, Georgia. “Mrs. Santa Claus’ Ride.” Zion’s Herald, vol. 51, no. 51, 17 Dec. 1874, p. 6, ia802307.us.archive.org/13/items/sim_zions-herald_1874-12-17_51_51/sim_zions-herald_1874-12-17_51_51.pdf.

Horton, M.B. “A New Departure.” Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine, vol. 99, no. 594, Dec. 1879, pp. 542–546, archive.org/details/sim_godeys-magazine_1879-12_99_594/page/542/mode/2up. Accessed 10 Nov. 2024.

Larcom, Lucy. “Visiting Santa Claus.” St Nicholas, vol. 12, no. 2, Dec. 1884, pp. 82–84, ufdcimages.uflib.ufl.edu/UF/00/06/55/13/00151/UF00065513_00151.pdf. Accessed 10 Nov. 2024.

“Missus Claus Asserted Her Rights.” Racing Nellie Bly, 4 Dec. 2022, racingnelliebly.com/trailblazers/missus-claus-asserted-her-rights%EF%BF%BC/. Accessed 10 Nov. 2024.

Palmer, Bell Elliott. Mrs. Santa Claus, Militant. Eldridge Entertainment House, 1914, catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100593075. Accessed 10 Nov. 2024.

Shelton, Ada Stewart. “In Santa Claus Land.” Young People’s Speaker Designed for Young People of Twelve Years, Penn Publishing Company, 1892, pp. 28–30, http://www.google.com/books/edition/Young_People_s_Speaker_Designed_for_Youn/uIUCAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0. Accessed 10 Nov. 2024.

Simpson, Jacqueline, and Steve Roud. A Dictionary of English Folklore. Oxford ; New York, Oxford University Press, 2016.

Steafel, Eleanor. “All Hail Mrs Claus! How the M&S Christmas Ad Went Fully Feminist.” The Telegraph, 14 Nov. 2016, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/work/all-hail-mrs-claus-how-the-ms-christmas-ad-went-fully-feminist/?ICID=continue_without_subscribing_reg_first. Accessed 13 Nov. 2024.

Thomas, Edith M. “Mrs Kriss Kringle.” St Nicholas, vol. 13, no. 2, Dec. 1885, p. 138, ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00065513/00165/images. Accessed 10 Nov. 2024.

Weber, Greg. “Santa Claus and His Works.” ThomasNast.com, thomasnast.com/cartoons/santa-claus-and-his-works/.

Note: Today’s feature image is AI-generated because there just aren’t many historical depictions of Mrs. Claus available in the public domain.

How fascinating that you got an AI-generated image of Mrs. Claus. And I LOVE the M&S commercial you found. She’s sneaky, but for a good cause, and she helps a kid, but not for that kid’s selfish reasons.

As for me, I think I know what I’ll be shopping for with my Christmas money. I look forward to shopping your merch.

Firat name? I like Eliza and Norah, but I feel like I should also be including Scandinavian names. Let’s have some fun, here in the comments: what do you think Mrs. Claus’s first name should be? .

LikeLike

Aww, thanks! My vote is for Norah as a first name!

LikeLike