If you prefer to read than listen, carry on, but this week the music is better if you listen…

Robert Schumann is a big name in classical music. His most recognizable piece is probably Träumerei, but he wrote lots of others as well. However, in his own lifetime, Robert Schumann wasn’t “the” Schumann. His wife was and this is her story:

A Focused Childhood

Clara Wieck was born on September 13, 1819. Her father had a piano store, and he taught piano lessons in Leipzig, Germany. Her mother was musical too, but she doesn’t come into this story very much because the Wiecks divorced. Clara’s mother wanted to keep her children, but in those days a mother had no rights.

Friedrich Wieck had plans for his little girl. He intended her to become a piano virtuoso, much in the way that Nannerl and Wolfgang Mozart had been decades earlier. It’s a little surprising that Wieck had this goal. Partly because that’s a hard thing to count on for any child, but also because Clara did not initially show much promise. She didn’t speak until she was four. People thought she was both deaf and stupid (Reich, 37). They were wrong, but how Wieck knew that is not clear to me.

Like Nannerl Mozart, Clara was the oldest surviving child. Unlike Nannerl, her father did not neglect her in favor of pinning his hopes on the boys (Reich, 34, 38, 39). Quite the opposite, Wieck’s behavior to his own sons appalled even observers of the time (Reich, 56). Clara was the one he counted on to make them rich.

By age seven, Clara spent three hours a day at the piano: one hour in a lesson with her father, two hours on her own for practice. School hours were minimal because it was deemed a waste of time. She had private tutors for the subjects her father thought important: French, English, music theory, composition, score reading, voice, violin, orchestration, and (belatedly) a little religion. She also spent hours every day walking outside for her physical health (Reich, 44-45).

This left very little time for playing, making friends, learning traditional feminine skills like cooking, or anything else, but Wieck thought that was all to the good and Clara complied.

Even her diary was not her own. Her father started it, and he wrote in it, using her voice as if she had written it. The entries she wrote were largely for handwriting practice. She copied his correspondence, including angry letters to clients and editors about unpaid fees and unfavorable reviews (Beer, 205; Reich, 42).

The Prodigy

By age eight, Clara performed in her home for her father’s friends. By age nine, she had given her first public appearance (Reich, 45). The following year she went on tour to Dresden and then to Paris.

These early concerts were a little different to what you might be imagining. When the Mozarts went on tour, they did public concerts, but the primary aim was to get noticed by the nobility, who would reward you for a private performance and maybe offer permanent employment.

An offer of permanent employment was never on the table for Clara. Her gender didn’t help, but the rise of the middle class also played a role. A much larger public with money and time meant you didn’t need a royal patron anymore. Instead you needed publicity.

Here’s how it worked: you arrive at a new city and you pay a visit to any friends or friends of friends you can round up. Hopefully one of them invites you to attend a party or a soiree or a private concert where you can play for the guests. Even at a tender age, Clara frequently attended parties that lasted until the wee hours of the morning.

You hope to get a small gift in return for your performance, but mostly you are there so the guests know who you are. So does any enterprising journalist who writes for the society and entertainment pages of the newspapers.

Once your name is in the papers, all you have to do is rent a concert hall, print flyers, distribute flyers, and sell tickets. You have a few days to get all this done because that’s how fast this market moves. You can’t schedule months or years in advance like nowadays because by that point some other performer will be the hot new thing in town.

You also need to hire supporting artists. This is because your audience is not composed of highbrow lovers of serious music. They are ordinary folks looking for fun and relaxation after a long day at work. They haven’t yet dreamed of channel surfing or streaming services, but they still expect variety. In her youth, Clara shared the stage with singers and chamber music ensembles, but also actors, speakers, and other performers, all of them hired by the main artist on just a few days’ notice (Reich, 258).

This means your event management skills are possibly even more important than your musical skills and Friedrich Wieck was exhausted. He said in Paris that “Clara can never compensate me for what I am doing for her” (Reich,53).

He thought of himself as a self-sacrificing, loving father, working himself to the bone to advance her career. But it is not at all clear that Clara had asked him to do this. And she certainly wasn’t the one pocketing the money. Nowadays there are laws about children in show business and rules about how they can be treated or paid. No such laws existed for Clara. It would be years before the word “exploitation” occurred to her (Reich, 55).

Sweet Sixteen

In between concert tours, Clara lived and performed in Leipzig, and her primary companions were her family and the men in her father’s circle. When did she have a chance to meet girls her own age? We have the guest list for her 16th birthday party. They are all adult men.

One was Felix Mendelssohn, another very big name in music history. He admired Clara’s music, said she played “like a little devil” (Beer 209), and he conducted the orchestra for the premiere of her Piano Concerto. Unlike Nannerl Mozart, Clara was encouraged to compose by all the men in her life (Schumann, 72, for example). Several famous musicians (Schumann and Brahms) particularly admired this Nocturne, which she wrote.

The other important man who attended Clara’s sixteenth birthday party was Robert Schumann. He had originally come to Leipzig to study law, which he had absolutely no interest in. Instead he talked Wieck into teaching him music and even into boarding him at the house.

Clara was nine when she met Robert, and he was eighteen. She was eleven when he lived in her house and studied side by side with her, twelve when she gave him a copy of her first published composition, thirteen when she premiered his second published work, fourteen when she dedicated her opus 3 to him, and sixteen when he published a series of variations on a theme composed by her.

She was also sixteen when he kissed her, and said no, no, he wasn’t engaged to another girl. In his mind this was true. It’s just the other girl didn’t know it. He hadn’t yet told her their engagement was over (Reich, 70).

Love Conquers All

Robert assumed a romance between him and Clara would be pleasant news to her father. In this, he was totally wrong.

Wieck had not been impressed with Robert’s diligence as a student. Among other things, Robert had said that music theory superfluous (Schumann, 41). Also, Robert had a partially misspent youth and a family history of mental illness. All things might have been forgivable if Robert had been rich, but he had only a modest income.

All these issues would have been considered valid reasons to object at the time, but I can’t say Wieck expressed them well. In fact, he exploded, and he said he would shoot Robert if Clara saw him again. Needless to say, Robert’s music lessons were over. Clara had no contact with him for a year and a half (Reich, 71).

By 1837, Clara was eighteen and beginning to want her independence. She reinitiated contact with Robert by asking a friend to deliver a letter to him. A surreptitious and passionate correspondence followed, including a marriage proposal, which she accepted (Schumann, 154-157).

They didn’t elope. They informed everyone, only Wieck was still adamantly opposed. After a disastrous interview with him, Robert wrote to Clara that “truly, his method of stabbing is original, for he drives in the hilt as well as the blade” (Schumann, 161).

If Wieck had stuck to the somewhat rational reasons I have already listed, he might have sounded like a loving, reasonable father. But he didn’t. Instead he stressed that Robert was socially awkward. He had poor handwriting and a silly, soft voice. You can hardly blame Clara for bristling at arguments like these. Robert thought Wieck just didn’t want to lose Clara’s income for himself (Schumann, 163).

The argument that did shake Clara’s resolve was that marriage would end her career. Wieck said so in no uncertain terms, and there was plenty of evidence to support him. Most female performers did give up the stage when they married. So Clara was very conflicted. She loved her father, she loved Robert, she loved her career, and it seemed she could not possibly hold on to all three. She wrote to Robert that “Must I bury my art now? Love is all very beautiful, but, but—” (Reich, 82).

Despite Clara’s reservations, they settled on a marriage date. In a fit of temper, Wieck sent her to Paris on tour alone. It was the first time she went alone, and you might think this was a show of confidence, but it wasn’t. He expected her to fail. He did this to prove to her how much she needed him (Reich, 88).

It was a bad miscalculation on his part. Years of dutifully copying Wieck’s correspondence into her diary had taught Clara exactly how a tour was done. What Clara actually learned was that she didn’t need him (Reich, 88).

But could she do it as a married woman? Wieck wasn’t the only one who thought not. I am sorry to tell you that Robert thought so too (Beer, 223). He wrote to her saying, “You are too dear, too noble, for the career which is to your father the aim, the crown, of existence. Are these few hours [on stage] worth so much time and expenditure? Can you look forward to a continuation of this as your whole vocation? No; my Clara is to be a happy wife, a contented, beloved wife” (Schumann, 192).

On her return from Paris, Clara found she was no longer welcome in her father’s house. But she still legally needed her father’s permission to marry, so it became a legal matter. Wieck informed the court that Robert was a bad composer (which was neither true, nor relevant). Also that he was stupid, vain, dishonest, and alcoholic. He also told the court that Clara was incapable of running a home (Reich, 97).

That last bit was really a low blow. It was true that Clara didn’t know cooking or many of the other feminine tasks. Wieck had never given her time or opportunity to learn.

The court ordered Wieck to pay all court costs, plus damages for slander, but victory in such a case was far from sweet. Both Clara and Robert found the experience traumatizing. Robert described it as living on the edge of a volcano (Schumann, 132). He was suicidal and very open about it. This was Clara’s first hint that a future with Robert would be both blissful and challenging, and the challenges were not the ones her father was warning her about.

With court permission, Clara and Robert were married on September 12, 1840, the day before she turned 21, and they were very happy. Clara wrote in her diary (which was now truly hers) that it was “the fairest and most momentous [day] of my life” (Schumann, 230).

A Wife or an Artist?

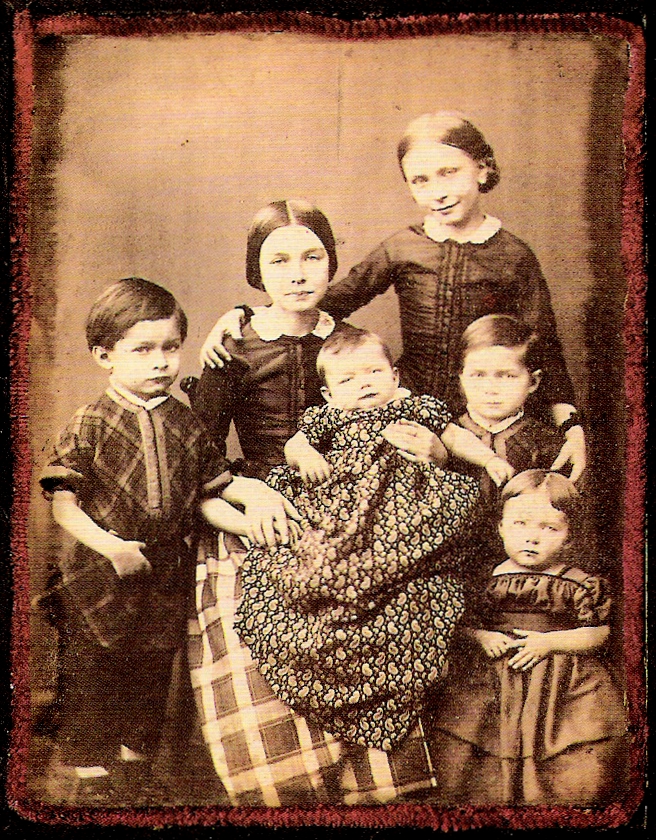

Clara was delighted to welcome her daughter Marie after one year of marriage, and she welcomed seven more children over the next thirteen years. But contrary to Robert’s predictions, she was not content to be a wife at the expense of being an artist. She performed at local concerts, and it was not enough.

She also realized that hired help was cheap. Wet nurses and maids were readily available for prices well below what she could earn on a tour.

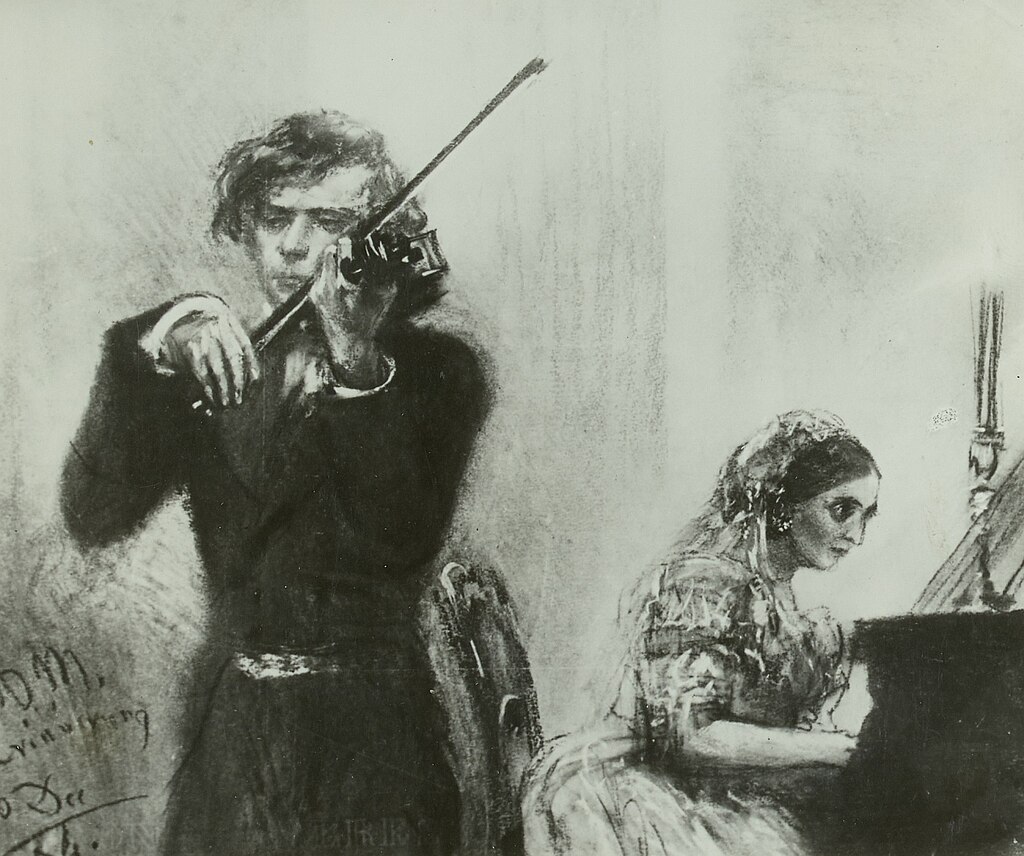

Only two years after her marriage, Clara was back as a touring artist. This transformation is all the more impressive when you realize that she was no longer a child prodigy and also that she faced a rebranding problem. The name she had already made famous was Clara Wieck. Now she was Clara Schumann. Not everyone survives this kind of rebrand. The fact that Clara did is proof of how very, very good she was.

Robert did not stop her from doing this, but neither was he happy. He had long felt a little insecure at the way her musical renown outstripped his (Schumann, 136). Also this was not the cozy home life he had imagined (Schumann, 143). If he went on the tour with her, he had to help with the managing and organizing, which he didn’t like. He loathed being introduced as Clara Schumann’s husband. Also it was difficult for him to work on his own career while he was on tour with her. Clara thought his music was brilliant, but Clara could earn more in three weeks of touring than he could earn in a year. He wasn’t happy to be left at home either. He wrote her long moping letters about how much he missed her and why hadn’t she written more often and had she completely forgotten him? (Reich, 113)

Basically, Clara was dealing with a fragile male ego here, and it was a little frustrating, but she didn’t let it stop her, anymore than she let pregnancy stop her. In some ways, she was her father’s daughter. Everything was sacrificed for the sake of the art and the box office. She may even have been confused that Robert didn’t see it that way.

On the other hand, Clara would be equally confused by any choice suggestions from a modern feminist. Clara was neither modern, nor a feminist. She adored Robert and told him so many times. She also thought that a man’s career comes first. She willingly gave up practicing at home during Robert’s composing hours because it would disturb him (Reich, 108). He loved his children, but no one (including Clara) expected him to take an equal share of the household tasks. That idea wasn’t in the public mind at the time (Reich, 156).

Robert showed his love for the children in other ways. He would probably be surprised and maybe embarrassed to learn that some of his most famous works would be the ones he wrote for their children’s music lessons, the Album for the Young. It includes the Happy Farmer, which if you’ve ever been or lived with a Suzuki child, you’ve heard.

An Agonizing Descent

I do not know whether Robert ever recognized it, but the fact that Clara never gave up her career turned out to be absolutely the right decision in her case. This is because Robert was ill. Like Jo Van Gogh, whose story I told a couple of weeks ago, Clara had married a man whose syphilis was in the dormant phase, giving him the illusion of health. It wasn’t going to stay that way, and the descent was agonizing.

In 1844, both Robert and Clara were working for the Leipzig Conservatory, but they had to withdraw because he had a complete mental breakdown. They moved to Dresden and Robert switched between periods of feverish creative output and severe depression. Clara supported the family. She also had her last four children within five years and composed some of her best works.

Clara also had an incident that my source skimmed over, when I would really like more details. In short, the uprising of 1849 meant that all men were pressed into military service. Robert was physically unable, but that would not have saved him. Clara smuggled him to safety, then walked home through a battlefield to get her children and led them away too all while being seven months pregnant (Reich, 127). Truly, she was a powerhouse of a woman.

In 1850, Robert took a job as a music director in Dusseldorf. By now he had learned a bit about his wife because he no longer expected her to give up her career. He did not accept the offer without asking what role his wife could fill (Reich, 133). He also took an apartment where she could have her own room and piano without fear of disturbing his composing.

Nevertheless, things did not go well because Robert was not well. He was a brilliant composer. He was not a brilliant director. He had neither the personality nor the health for it. Clara was extremely prickly about any criticism of him, and in fact she eventually resigned the job for him. Without consulting him (Reich, 137).

By now Robert was experiencing auditory hallucinations and terrible insomnia. On February 10, 1854, his final breakdown began. Clara stayed with him night and day while he suffered in ways that no one of this time period could explain or treat. On February 26th, Clara stepped into another room to speak to the doctor for a few minutes. While her back was turned, Robert slipped out of the house and deliberately threw himself into a river.

He was rescued, but he did not come home. He was sent to an institution, and his children never saw him again. The child Clara was carrying at the time never saw him at all.

Nineteenth century mental institutions suggest all kind of horrors, but as far as I can tell Robert’s situation was better than most because Clara paid the bills regularly. He had his own suite of rooms, and he had a piano. He took daily walks in the gardens. But his doctors would not allow his family to visit. They told Clara that her presence would only agitate him further.

Visits from friends were allowed, and they reported to Clara an endless seesaw of yes, Robert was better and would be cured soon, but then, no, Robert was no better and probably never would be. Finally in 1856, the doctor said that Clara should come after all because Robert wasn’t going to make it. Clara came, and he died two days later (Reich, 150).

A Widow and an Artist

At the time of his death, Robert was known as a composer mainly to a handful of enthusiastic fans. The famous Schumann was Clara. And it was a good thing that was true because most 19th century women in her situation would have been destitute. As it was, Clara could proudly refuse all offers of financial help. She made arrangements for the children’s care and education. She paid for it by performing and teaching music. She gave up composing herself. She had always doubted her ability to do it well and even doubted the ability of any woman to do it well (Beer, 229). Like I said, she was not a feminist.

As a performer, Clara had incredible longevity: 60 years on the stage. She promoted Robert’s work to the end. So that by the end of her life, she was known as Clara Schumann, wife of Robert Schumann, instead of the other way around.

In her youth, she was part of a variety show and played crowd-pleasing music by composers I’ve never heard of. By the end of her life, young pianists were imitating her taste, and she was teaching audiences to love Bach, Beethoven, Chopin, Mendelssohn, Schubert, and Schumann: all the masters you would still expect in a modern concert.

Clara lived long enough to have made recordings. But sadly for us, she didn’t (Kaplan, 20). That is why in the long run Robert’s fame was bound to outstrip hers. We can only read about her best work. A composer’s art we can still experience, usually without ever realizing that without the advocacy of people like Clara, we’d probably be playing music by someone else.

Clara died in 1896, having been a widow for 40 years. She was swiftly followed in death by someone else. Someone whose music she influenced possibly even more than Robert’s, someone who was also in love with her. I had no room to day for the story of Clara and Johannes Brahms, but I’ll be telling that story as a bonus episode, which you can get on Patreon or on Into History.

Selected Sources

CHERNAIK, JUDITH. “Brahms’s Clara Themes Revisited.” The Musical Times 160, no. 1949 (2019): 37–50. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26860067.

CHERNAIK, JUDITH. “Schumann and Clara: A Musical Intertwining.” The Musical Times 159, no. 1944 (2018): 89–105. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44862853.

Kaplan, Nanette. “Celebrating Clara: A 200TH Birthday Tribute To‘The Other Schumann.’” American Music Teacher 69, no. 1 (2019): 18–23. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26815906.

Reich, Nancy B. Clara Schumann, the Artist and the Woman. Ithaca, N.Y. : Cornell University Press, 1985.

Schumann, Robert. The Letters of Robert Schumann. Edited by Karl Storck. Translated by Hannah Bryant. EP Dutton and Company, 1907. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/81/The_letters_of_Robert_Schumann_%28IA_cu31924022315174%29.pdf.