Please take a moment to vote for me in the Women Podcasters Awards! I’m in the History Category, and voting is free.

I found Mileva’s story difficult for several reasons. Ever since long-time listener Kate brought Mileva to my attention, I have seen dozens of social media posts that say something provocative like: Mileva was the real genius! Down with the patriarchy! Inevitably someone else will rudely respond: it’s all a hoax, you nimwit, Mileva didn’t do anything.

As usual, the truth is somewhere in between the social media hype, but the debate will go on because the sources are sketchy. I’ll do my best here.

Early Studies (as the only girl)

Mileva Marić was born in what is now Serbia on December 19, 1875. When she showed talent in math and physics, her parents had both the desire and resources to encourage her. Mileva attended high school at a time when most girls didn’t and even got special permission to attend lectures that were only for boys (Milentijević, 22-27; Esterson, Einstein’s Wife, 8).

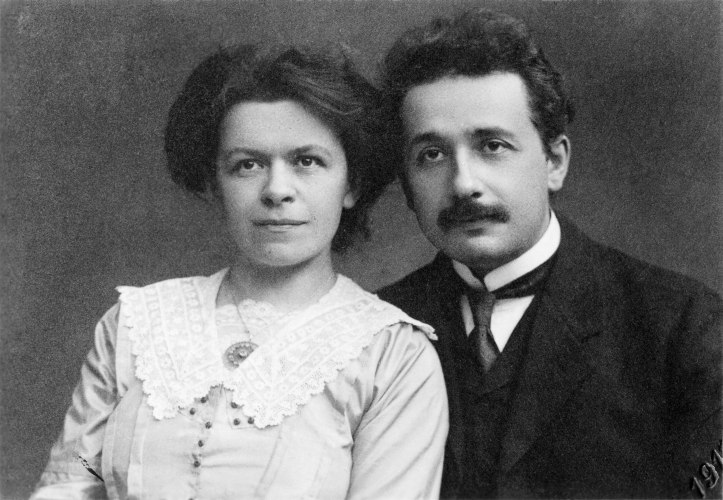

In 1896, Mileva moved to Switzerland and entered the Zurich Polytechnic school to study math and physics. In her class of five students, she was the only woman, and the oldest at nearly 21. The youngest was a 17-year-old pipsqueak named Albert Einstein (Milentijević, 32). Only twenty women in the whole country of Switzerland were studying any form of natural science or math that year, and it takes guts to do something so unusual. Her grades prove she was certainly capable of keeping up (Milentijević, 32; Esterson, Einstein’s Wife, 15).

One semester, Mileva went to Heidelberg as a visiting student. Her classmate Albert missed her (Esterson, Einstein’s Wife, 28). He wrote her a letter, which we’ve lost, but her answer still exists. She says:

“It has now been quite a while since I received your letter, and I would have replied immediately, would have thanked you for the sacrifice involved in writing four long pages… but you said that I should write you someday when I happened to be bored. And I am very obedient… I waited and waited for the boredom to set in; But so far my waiting has been in vain” (Milentijević, 32).

On Mileva’s return to Zurich, they studied together daily. Over school holidays, they wrote to each other about the kinetic theory of gases (Esterson, Einstein’s Wife, 29), the nature of infinity (Milentijević, 40), and thermoelectricity (Milentijević, 53). Perhaps not the most romantic of love letters, but they both passed their intermediate exams.

Albert’s mother had not met Mileva, but she was adamantly opposed to her son’s new love interest. Mileva was too old (“By the time you’re 30, she’ll already be an old hag!” (Gagnon)). Also, Mileva was genetically inferior, according to Albert’s mom. It was true that Mileva had a slight limp, but her real offense was being Serbian, not German.

The irony of a German Jew calling someone else’s genetics inferior does not escape me, but the basic concept of a genetic superiority complex here was very, very common in the early 20th century. The Nazis were still several decades away from seizing power. The horrific consequences of allowing one group of people to decide whose genes were unacceptable were not yet photographed and documented and included in everyone’s basic education.

Albert himself would later parrot some of his mother’s opinions here, but at the moment he was in love and untroubled by genetic bigotry. He did understand that he needed a job to get married.

Joint Studies with Albert Einstein

In July 1900, Albert passed his final oral exam. Mileva failed (Milentijević, 58). All was not lost, however. Retakes were possible

Albert had his degree, but no one offered him a professorship (Milentijević, 60). To boost his credentials, he needed to publish, and in 1900 he and Mileva together were working on a paper on capillarity, or the movement of liquids based on surface tension. It’s the mechanism that you see when drops of water stick to your windshield, rather than rolling down.

We know they worked on this together because of their own choice of pronouns. Mileva wrote a friend that “We also sent a copy” of the paper to a prominent physicist because “we would like to know what he thinks of it; I hope he will write to us.” Albert also referred to it as our paper (April 4, 1901) (Milentijević, 69).

But pronouns are all we’ve got. No details whatsoever. The pro-Mileva camp wants to believe she was the guiding genius behind this paper and all the papers to come. The anti-Mileva camp believes she did no more than proofread the final draft or maybe double check Albert’s math.

To me it seems likely that her contribution was something in between those extremes. They were used to studying and working on physics together. Why would that change?

However, the paper was published without Mileva’s name on it. Nowadays, it’s normal for scientific papers can have dozens of authors, so the absence of Mileva’s name has been used to say she didn’t do anything of significance.

That argument is nonsense. Both Albert and Mileva lived in a world where it was completely normal for a woman to help the man in her life without any public acknowledgement. It was his job prospects that needed a boost, not hers. It probably didn’t occur to either of them to include her name. This is not proof that she was a major contributor, of course. It’s just equally not proof that she wasn’t.

An Unexpected Complication

The paper was done, but the job remained elusive. Albert moved to Italy to expand his search. No luck on that front, but while there, Mileva came down for a brief visit to Lake Como.

Within weeks, Mileva was back in Zurich, and she was pregnant. A few weeks later she failed her oral exams again (Milentijević, 85). We don’t know why she had such trouble with these exams. Maybe she was genuinely not up to the standard. Maybe she spent too much time on Albert’s work instead of her own. Maybe she had morning sickness and anxiety. Maybe the Polytechnic never intended to let a woman graduate. We just don’t know.

We also don’t know what she said on August 3, 1901, when she went home to explain her situation to her parents. It can’t have been fun, but they stood by her (Milentijević, 87).

My major source today says that Zurich was a center of the birth control movement, and abortions were available, so Mileva and Albert must have had their daughter Lieserl on purpose. To me this makes about as much sense as saying that because my city is the international chess capital, I must know a lot about chess. I can assure you, I don’t. Mileva was a young, unmarried woman living away from her family. Her classmates and professors were all men. She and her roommates had all been raised in a culture that expected abstinence before marriage.

Who would have told her about birth control?

This also presupposes that Mileva knew she would begin physical intimacy when she went to Lake Como. It’s far more likely it was unpremeditated, at least on her part. As for an abortion, if she knew how to get one, she might well have thought that was the most immoral idea of all.

Besides, Albert promised to marry her and to love the baby. Enjoy this moment while it lasts because Albert’s behavior isn’t going to stay so pretty.

When baby Lieserl was born in January 1902, her parents were still unmarried. Albert had was the promise of a job in the patent office at Bern, on a salary that wasn’t really enough to support a family (Milentijević, 93). The wedding did not happen until a full year later in January 1903. Mileva moved to Bern. Lieserl did not. She simply vanishes. Probably that means she was sent out for secret adoption, and probably it was because Albert thought an illegitimate child would damage his career. He may have been right on that, but it is hard to imagine this being anything other than traumatic for Mileva. The whole thing was hushed up so well that if she grieved, she grieved in silence. We still don’t know what she thought.

Boredom by Day, Physics by Night

In Bern, Albert worked eight hours a day, six days a week in the patent office. He was very bored. Mileva kept the house and may also have been bored. There are numerous accounts that say the both of them spent their evenings on math and physics. Given their background, it would make sense. However, most of these accounts are from long afterwards or are second hand or even third hand (Martinez; Esterson, Einstein’s Wife, xx; Carroll). They aren’t very good as historical sources. Hence the debate on social media.

The hard work of one or both of them resulted in what science historians call Einstein’s annus mirabilis or Year of Miracles. In 1905, Einstein published four groundbreaking papers. He wrote on the photoelectric effect, which won the Nobel prize. He wrote on Brownian motion, which gave substantial evidence for the existence of atoms. He wrote on the special theory of relativity, for which he would become most famous, and he wrote on mass-energy equivalence, otherwise stated as e=mc2. Every one of these four papers revolutionized the field of physics.

Mileva is not credited on any of them. But both Albert and Mileva occasionally still use the pronoun “our” in their letters to others. And again, why would she not be involved in work she knew a lot about, and he could do only at home in the evenings after work? It would be strange if she didn’t contribute. But how much and in what ways? There is no evidence at all.

Mileva, feeling secure in her marriage, did not see any reason to complain about credit. When Albert and a friend named Habicht applied for a patent for an invention that the three of them had worked on, Habicht asked why it had only the names Einstein and Habicht on it. Mileva said it didn’t matter that she wasn’t specified because she and Albert were ein stein or literally, one rock. It’s a pun on the name. They acted as a unit (Milentijević, 112).

The appearance of their son, Hans Albert, was also a joint effort.

The Physics World Takes Note (of one of the Einsteins)

The physics world belatedly decided Albert Einstein was worthy of a professorship. As the family prepared to move back to Zurich, there begins to be a hint of future trouble. Mileva wrote to a friend that Albert was:

“now regarded as the best of the German-language physicists, and they give him a lot of honors. I am very happy for his success, because he really does deserve it; I only hope and wish that fame does not have a harmful effect on his humanity” (Milentijević, 140).

It’s an odd thing to say about your own husband, so possibly she already had reason to worry?

Mileva helped Albert prepare his first lectures. Some of his surviving lecture notes are in her handwriting (Milentijević, 144). She also gave birth to their second son Eduard, generally called Tete.

In pursuit of better and better jobs, Albert moved the family to Prague and then back to Zurich. All this was good for his career, but not good for Mileva. By 1913, Albert was having an affair with his cousin Elsa, and Mileva was deeply unhappy. When Albert took a job in Berlin, it was perfectly clear that the point of this move was to be closer to Elsa (Milentijević, 165).

Mileva reluctantly moved again, but Albert had no interest in being reasonable. He sent Mileva a list of terms on which he would be willing to continue cohabiting with her: She was to take care of his clothes and laundry, serve him three meals a day in his room, and keep his room neat and tidy. She should not expect him to stay at home with her or to go anywhere with her, and she should leave his presence immediately if he requested it (Milentijević, 175-176).

In other words, he was willing to accept her as an unpaid servant, but not as a wife. It was appallingly harsh, and since he was unwilling to negotiate, Mileva agreed to a formal separation.

A Discarded Woman

She left Berlin on July 29, 1914, with a legal separation document that promised her an annual stipend, her children world live with her in Zurich, and she would never ever have to give them up to Albert’s relatives. As devastating as this was, it was a lot more than many discarded women got (Milentijević, 177).

Even so, life was not easy. Getting a job was out of the question. She was not only a woman, she was a woman separated from her husband, with two small children. Mileva and Albert argued over bank accounts and currency exchanges. Albert blamed Mileva if Hans Albert didn’t write letters to him, but also forbade her to make the boy write or tell him what to write (Milentijević, 183). In 1916, Albert said separation was not enough, he wanted a divorce. Mileva had a serious mental and physical breakdown.

When Albert heard she was hospitalized, he first claimed she was faking it. He wrote to their mutual friend Besso that “you have no idea of the natural craftiness of such a woman” (Milentijević, 199). When Besso (who had actually seen Mileva) assured him the illness was real, Albert switched tactics and said he had no patience for women who “simply fall apart” without a man to cling to (Milentijević, 199). He bemoaned his legacy, having unintentionally fathered children with a genetically deficient woman. Then he proved that he had absolutely no sympathy for unemployed single mothers, by adding:

“As concerns my wife, please consider the following. She has a worry-free life, has her two fine boys with her, lives in a lovely area, can use her time freely, and basks in an aura of abandoned innocence. The only thing she is missing is someone to dominate her. Now is it really so terrible in your eyes that I fled from this responsibility?” (Milentijević, 200)

I have no idea what Besso said in response to this, but I hope it was acid.

Mileva spent the next several years in and out of the hospital. Tete was also sickly. The medical bills were mounting, Albert sent less money than expected, and by 1918 poor Hans Albert, age 14, was reduced to arguing with his father by letter to get child support money and medical care for his younger brother (Milentijević, 218-219).

The Divorce Terms

When the divorce terms were finally finalized, Albert promised that if he ever won the Nobel prize, the money would be deposited in a Swiss bank. The interest would be Mileva’s. The capital she could not touch without Albert’s consent. On her death or remarriage, it would go to her sons (Milentijević, 235).

These terms were approved by the court on February 14, 1919 (Milentijević, 235). Albert married Elsa in June of the same year. As expected, he did win the Nobel, and the prize money came through in 1922. He deposited it in a New York bank, not a Swiss one. When Mileva pointed this out, he said interest rates were better in America. Then he asked for a signed document stating that the prize money was his sons’ inheritance, and they would not protest if he left everything else to his new family. To Mileva this was unacceptable. The prize money was hers, and it would be her inheritance to her sons. They ought to still have full rights to their share of Albert’s estate.

It may be that now, belatedly, she thought it would be wise to document how she had helped with the papers of the annus mirabilis, to show that she deserved prize money, not just as a wife, but as a collaborator. We, unfortunately, do not have the letter she wrote, so we can’t know how much she claimed to have helped, or what exactly she said, or how well she worded it. Perhaps she was rude, angry, and unreasonable.

But I find it hard to imagine her words could have justified a response as brutal as the one Albert sent back. His letter is perfectly well preserved for posterity. He said:

“You really gave me a good laugh when you started threatening me with your memories. Doesn’t it ever dawn upon you for even a single second that no one would pay the least attention at all to your rubbish if the man with whom you are dealing had not perchance accomplished something important? When a person is a nonentity, there’s nothing more to be said, but one should then be modest and shut up. I advise you to do so… Now go humbly for once and don’t fly off the handle in your usual style. If I were not really good to you, I would not say what is on my mind in this way. Not only children need a bit of thrashing but also grownups and especially women” (Milentijević, 287).

It is sometimes said that Mileva never claimed to have been a major collaborator, and that proves that she didn’t contribute anything significant. But those people are ignoring the reality of life for women. If she had pressed her claims early, many would have disbelieved her and maybe thought less of the work itself. As a bitterly divorced woman, they were even less likely to believe her. Her only hope was to get Albert himself to acknowledge her contributions, and he refused in the most offensive manner possible. In the face of this kind of contempt, what could a financially dependent woman possibly say?

The Growing Storm

Mileva’s next plan was to invest in real estate. She asked Albert and he agreed that she could use some of the prize money principal as a downpayment on some apartment buildings. That way she could have a place to live herself and earn rent money from tenants. This worked rather well for a while but eventually became a problem. The economic downturn in the 1930s left her with tenants in arrears, mortgage payments she could no longer meet, and New York banks that actually did not pay rates better than Swiss banks.

Tete was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Treatments were available, but uncertain and expensive. His behavior when at home was unpredictably terrifying. Hans Albert had finished school, gotten a job, and moved to the US, but it was increasingly clear that Tete would never do any of that.

In March 1933, the Nazis came to power in Germany. Albert Einstein was a Jew. His Berlin apartment was ransacked and his bank accounts frozen. Albert turned in his passport, renounced his citizenship, resigned his job, and fled.

Mileva kindly offered to let him and Elsa come live with her in Zurich. He felt (and with good reason) that Switzerland was not far enough. But he did come visit and some of the past was a little healed. He promised to send more money to help with Tete’s medical bills (Milentijević, 343). But he moved to America.

After he left, a frightened Mileva wrote him, “You are my last and only hope. I must ask you once again not to forget me” (Milentijević, 343). Albert promised he would not.

You may have noticed (as I did) that we sailed through the World War I years with no mention of it. Mileva had personal problems at the time, and she lived in a neutral country. The war was not the biggest issue for her. Switzerland stayed neutral again this time, but the threat of German invasion was very real and very personal. Mileva was not a Jew, but Tete was. He was also mentally ill. A double strike against him.

After 1941, Mileva could get no news on her Serbian family, nor money from her recently deceased parents’ estate, nor documentation on her grandparents’ religious affiliation, which was the only possible proof that she herself wasn’t Jewish (Milentijević, 374). After 1942, she could get no news on her American family either (Milentijević, 377).

It must have been very, very dark days for Mileva.

The war came to an end at last, but her creditors did not. She managed to sell one of her buildings, and she used the money to establish a guardianship to take care of Tete (Milentijević, 396). I am pleased to say that Albert did help her out with settling some of the issues with creditors. Maybe not as much as he should have done, but he did do some.

Mileva died on August 4, 1948. Her apartment was cleared out by her daughter-in-law, Hans Albert’s wife. It was only years later in reading through her box of papers that Hans Albert found out he had an older sister. No one had ever told him before.

At the end of this research, I can find no way of spinning Mileva’s story to be anything other than a tragedy. It was a hard life, and so much of it unnecessarily so. I have no idea how much she contributed to Einstein’s work, but I’d guess that it was more than she originally got credit for and less than some social media posts claim. If you have thoughts, leave a comment below.

Selected Sources

Carroll, Hannah. “Does Mileva Einstein-Marić Deserve Credit for Albert Einstein’s Discoveries?” Lostwomenofscience.org, 2022. https://www.lostwomenofscience.org/post/does-mileva-einstein-maric-deserve-credit-for-albert-einsteins-discoveries.

Esterson, Allen, and David C Cassidy. “Does Einstein’s First Wife Deserve Some Credit for His Work? That’s the Wrong Question to Ask.” Time. Time, March 14, 2019. https://time.com/5551098/mileva-einstein-history/.

Esterson, Allen, David C Cassidy, and Ruth Lewin Sime. Einstein’s Wife : The Real Story of Mileva Einstein-Marić. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Mit Press, 2019.

Gagnon, Pauline. “The Forgotten Life of Einstein’s First Wife.” Scientific American, December 19, 2016. https://www.scientificamerican.com/blog/guest-blog/the-forgotten-life-of-einsteins-first-wife/.

Martínez, Alberto A. Science Secrets : The Truth about Darwin’s Finches, Einstein’s Wife, and Other Myths. Pittsburgh: University Of Pittsburgh Press, 2011.

Milentijevic, Radmila. Mileva Maric Einstein : Life with Albert Einstein. New York: United World Press, 2015.

Sime, Ruth Lewin. “Women in Science: Struggle & Success, the Tale of Mileva Einstein-Marić, Einstein’s Wife.” MIT Press, March 14, 2019. https://mitpress.mit.edu/women-in-science-struggle-success-the-tale-of-mileva-einstein-maric-einsteins-wife/.

I read your transcript this time around. Thanks for publishing those; I appreciate it. As usual, I’m interested to read your take on it after you did the research yourself. It’s an unknown side of Einstein’s life that needs to be told, however tragic.

LikeLike