It’s a rare historical figure so famous they get a holiday. In the United States, Martin Luther King, Jr., is so honored partly because he challenged Americans to live up to their own ideals and extend freedom and equality to people of all races. Partly because he delivered this challenge peacefully, with no violence. Partly because he paid for this cause with his life. And partly because he had a great wife, who stood by him.

A Childhood of Poverty

Coretta Scott was born April 27, 1927, in Perry County, Alabama. Her family lived in a 2-room house on a dirt road. She began farm work at age 6 (King, My Life with Martin Luther King Jr, 25-26). Her father had a 6th grade education and her mother, Bernice, had a 4th grade education (King, My Life with Martin Luther King Jr, 32; McCarty, 7).

As poor as their circumstances were, the Scott parents were determined to make things better for their kids. Coretta’s mother told her, “You are just as good as anyone else … You get an education and try to be somebody. Then, you won’t have to be kicked around by anybody and you won’t have to depend on anyone for your livelihood, not even on a man” (King, My Life with Martin Luther King Jr, 34).

Bernice meant that and she sacrificed for it. When Coretta and her older sister were ready for high school, Bernice scrounged up the tuition money because it wasn’t free (King, My Life with Martin Luther King Jr, 36). Also, Bernice drove the bus, because the county wouldn’t pay for that (McCarty, 6).

High school was a revelation to Coretta. As mandated by state law, it was an all-black school. One curious twist of the way segregation worked was that teachers in black schools were often better educated than their counterparts at white schools. This was because if you were a smart, motivated, white college graduate, you probably had a range of possible career options. Teaching might not be your top choice. If you were a smart, motivated, Black college graduate, your options were more limited, so you were far more likely to choose teaching.

As Coretta herself said:

“These college graduates who taught me, I soon saw, were different from other people I knew. They had greater freedom of movement: they went on trips; they visited cities; they knew more about the world. They had greater economic security. Although I know they weren’t paid high salaries, they didn’t seem to worry about money the way everyone else I knew did. They got more enjoyment out of life: they knew many different kinds of people; they could talk with pleasure about a lot of different subjects; they enjoyed books and music. They were even aware of the need for improving the political status of the Negro in the South (but for fear of losing their jobs, they remained silent). I concluded that the difference between them and the other people I knew—who seemed to me equally good people—lay in their educations. Because of these differences I decided that I had to go to college myself” (McCarty, 9).

[One note: If I’m using the word Negro today, it’s because it’s a direct quote. That’s the word Coretta and Martin used for themselves.]

Coretta’s plan wasn’t just to go to college, but specifically to go to college in the north, on the dubious theory that race relations would be better there.

A Jim Crow Childhood

As a pasty white person myself, it pains me to say it, but up until this point Coretta’s experience with white people was uniformly negative. Like all African Americans, Coretta was expected to get off the sidewalk if a white person was passing and to use separate toilet facilities. She was not welcome in white restaurants or in the white sections of public transportation (King, My Life with Martin Luther King Jr, 24; National Park Service).

As US citizens, Coretta’s parents were constitutionally guaranteed the right to vote, but practically speaking, they could not exercise that vote. The 1901 Alabama state constitution was written for the express purpose of establishing white supremacy. That’s not me saying that, nor is it a matter of interpretation. It’s a direct quote from the president of that Constitutional Convention. President John B Knox said in his opening address: “And what is it we want to do? Why it is, within the limits imposed by the Federal Constitution, to establish white supremacy in this state” (Proceedings, 8).

The resulting constitution required voters to pass literacy tests, unless your grandfather was a veteran. Most white people had a Civil War vet in the family history. Most Blacks did not. Their grandfathers were still enslaved during the war. Also, there were poll taxes, which hit all female voters quite hard, but there’s no doubt that they hit female voters of color hardest of all. These and other more intimidating measures were so effective that as late as 1965, one Alabama county had only 156 registered black voters, even though they had 15,000 African-American adults (Brown-Dean, 5).

The same constitution mandated segregated schools and forbade interracial marriage. On a far more personal note, Coretta’s father had built a lumber mill. When he refused to sell it to a white man, it mysteriously burned down. Their home burned down too (King, My Life with Martin Luther King Jr, 38-39).

Going North

With this as her background, Coretta decided to try Ohio for college. At Antioch College, she was one of six African-American students (McCarty, 10). It wasn’t easy. She had been valedictorian of her high school, but she was still behind academically. She worked part-time jobs to pay the bills. When she was almost done with her education degree, the local public school system wouldn’t let her be a student teacher. She refused to do it in a segregated school, so she ended up in the Antioch laboratory school. She got her degree, but she was also disillusioned about racism in the North. It wasn’t all peace and love and equal rights, not even there (King, My Life with Martin Luther King Jr, 43).

Perhaps because of that negative experience, Coretta did not take a teaching job. She chose to pursue her other love: music. She had grown up singing in the church choir. She’d taken lessons, and the New England Conservatory in Boston accepted her as a graduate student.

She was there in 1952 when Martin Luther King, Jr, got her number from a mutual friend and asked her out on a date. They met up for lunch and Coretta thought he was short and unimpressive (King, My Life with Martin Luther King Jr, 54). Physically, that is.

His words were very impressive. He could discuss philosophy. He could discuss music. He was already an ordained minister with a powerful presence while preaching.

They were married June 18, 1953. Later that year, they both finished their degrees.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott

In 1954 Martin accepted a job offer from the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. He took the job in the same month that Brown vs. Board of Education made school segregation by race illegal. This was an unpopular decision in much of Montgomery. Race relations were tense.

The Dexter congregation were mostly well educated and professional. Martin and Coretta were good with this crowd. She helped plan the worship music and organized social activities. Martin wrote sermons with her input and encouraged church members to vote and join the NAACP. They also welcomed their first child.

They had been in Montgomery only 18 months when Rosa Parks made history by refusing to give up her bus seat to a white man. The subsequent boycott of the bus system was not Martin’s idea, but he was not very far down the list of people the organizers called on day one. At the first meeting, the supporters elected Martin president. It was the beginning of his leadership in the dangerous world of civil rights activism.

Accordingly, the death threats began to flow in. Martin was arrested, supposedly for speeding. Their home was bombed, and it had still been only a few weeks since Rosa had sparked the outrage. In every case, Martin and Coretta reacted calmly and nonviolently, but also refused to stop doing what they were doing. This was the essence of Martin Luther King’s message to his people: the cause is just and it needs fighters, but the fight must be peaceful. An outbreak of violence would only make everything worse (King, My Life with Martin Luther King Jr, 123-130).

And they saw success. Just over a year after Rosa Parks stayed in her seat, the Montgomery bus system integrated. The very next day, someone shot bullets through Coretta’s front door.

The successful bus boycott brought Martin to the attention of the nation. Regional groups began seeking Martin’s thoughts and words and presence. Coretta’s too. She traveled, spoke, and listened with him. Being pregnant didn’t stop her.

They were working together at the church and in the civil rights movement. But it wasn’t easy. For one thing, Martin was gone so much, Coretta often felt like a single parent. It was the 1950s, so if he traveled she took care of the kids. If she traveled, well, she still took care of the kids. She was more tied down than he was.

Also, Martin had been reading about Gandhi. They even visited India to learn more about what Gandhi had accomplished by nonviolent means. Gandhi got rid of all material things and insisted that his family do the same. Martin found this idea very attractive (King, My Life with Martin Luther King Jr, 160-161). I covered Gandhi’s wife Kasturba a couple months ago (episode 14.15) and there’s no doubt that Kasturba found Gandhi’s ideas very, very hard at first. But Kasturba also came from a culture where stamping her foot and refusing her husband wasn’t really an option. 1950s America was not a feminist paradise, but it was more feminist than turn-of-the-century India.

Coretta told Martin that (unlike him) she had grown up poor. Her children were not going to suffer unnecessary hardships. They were middle class, and they would stay middle class. No, you cannot give away everything to the cause (McCarty, 26-27).

So he kept his salary, and dressed the way middle class people are supposed to dress, and paid for the decent house and all that. But when donations to the cause started flowing in (and they did), they were for the cause. Not for the enrichment of the King family.

In 1959, they moved to Atlanta, where Martin was from. Coretta traveled widely, giving speeches as far away as Switzerland (McCarty, 34).

Birmingham Jail

Their fourth child was only a few days old when Martin was arrested in Birmingham. Coretta did not even know where he was being held or if he was dead. President Kennedy personally intervened to get her a phone call. The jail officials later claimed they hadn’t denied him a call and suggested Coretta’s panic was just postpartum depression (King, My Life with Martin Luther King Jr, 224-225; McCarty, 36). <Sigh>

But whatever the truth of it, this particular arrest worked in Martin’s favor. It was in this solitary confinement that Martin wrote his powerful “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” There is too much of it to quote here, and all of it is good, but here is just a part:

“One day the South will recognize its real heroes. … They will be old, oppressed, battered Negro women, symbolized in a seventy-two-year-old woman of Montgomery, Alabama, who rose up with a sense of dignity and with her people decided not to ride the segregated buses, and responded to one who inquired about her tiredness with ungrammatical profundity, “My feets is tired, but my soul is rested.” They will be young high school and college students, young ministers of the gospel and a host of their elders courageously and nonviolently sitting in at lunch counters and willingly going to jail for conscience’s sake. One day the South will know that when these disinherited children of God sat down at lunch counters they were in reality standing up for the best in the American dream and the most sacred values in our Judeo-Christian heritage.” (King, “Letter from Birmingham Jail”)

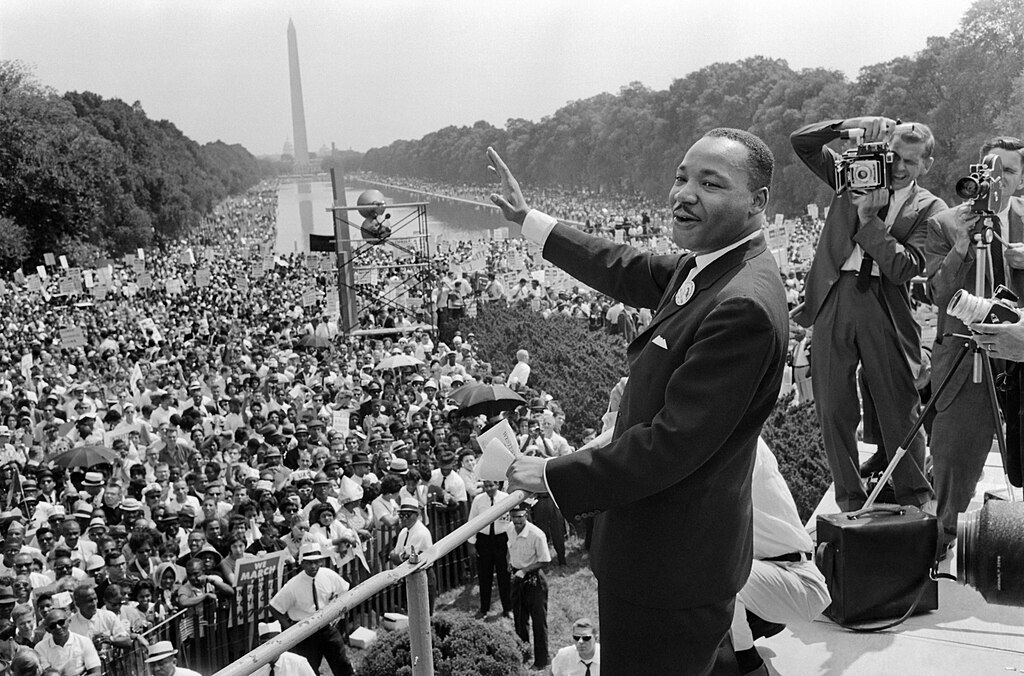

March on Washington

It was also while Martin was in Birmingham Jail that Coretta suggested a March on Washington. That march occurred only a few months later. Coretta had a seat directly behind Martin as he gave his most famous speech to an audience of 100,000 people in person and a televised audience of millions. He said, among other things, that:

“I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up, live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal… When we allow freedom to ring from every town and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, ‘Free at last! Free at last! Great God A-mighty, we are free at last!” (King, My Life with Martin Luther King Jr, 239-240).

Another thing that happened in the eventful year of 1963 was that President Kennedy was assassinated. Coretta watched Jackie Kennedy, a young mother, bury her husband in a very, very public manner and “it was as if watching the funeral, I was steeling myself for our own fate” (McCarty, 38).

This would continue to weigh on her mind over the next several years of rallies, fundraisers, concerts, and meetings, all of them high-profile, all of them potentially dangerous. When Martin won the Nobel Peace Prize, Coretta thought that $10,000 of the award should be set aside as a trust fund for the children. In my view, this was 100% reasonable. If something were to happen to Martin, how would Coretta provide for these kids? It was the 1960s and she was a black woman. An educated one, but still, a black woman. Her options would be limited. But Martin disagreed. He said the money was for the civil rights movement, and he donated all of it to various civil rights organizations (McCarty, 43).

The Accusations

The increased visibility was good for the Civil Rights Movement, but bad for the Kings personally. The FBI began wiretapping their home and Martin’s office. In 1964 Coretta opened a package mailed to Martin. It included tapes of FBI wiretaps and a letter that can only be described as blackmail. It said:

“Lend your sexually psychotic ear to the enclosure… You will find on the record for all time your filthy, dirty, evil companions, males and females giving expression with you to your hideous abnormalities… King, there is only one thing left for you to do. You know what it is… There is but one way out for you. You better take it before your filthy, abnormal, fraudulent self is bared to the nation” (Gage).

Setting aside (for the moment) whether any of this was true, you can just imagine how Coretta must have felt. I have lost track of how many betrayed wives I have covered on this show, but Coretta’s response was certainly among the classiest. In an interview after the fact, she said she didn’t ask Martin if it was true because “I wouldn’t have burdened him with anything so trivial… all that other business just didn’t have a place in a very high-level relationship that we enjoyed” (McCarty, 44).

In other words, she trusted Martin and these accusations were just another in a long list of slimy, unethical assaults on him. She maintained this attitude for the rest of her life. Her memoir does’t even mention this (King, My Life with Martin Luther King Jr). Personally, I think she was wise to take this approach. It’s a form of self-care.

But in the research for this episode, it came to my attention that a lot of other people don’t have this kind of trust in Martin. To the extent that one blog post I read said that growing up, the author learned two things about Martin Luther King: he was a Communist and he was an adulterer. That is not even close to what I learned about him growing up, but since it seems to be prevalent, let me address the evidence.

Initially, both those accusations came from the FBI, which was headed and run by a man who was absolutely hostile to Martin from the word go. J Edgar Hoover had no love for African-Americans generally and particular venom for anyone who had ever so much as spoken with anyone who might at any time have sympathized with any Communist.

Martin was not and never had been a Communist. The FBI’s own recordings prove that (Gage). But he had spoken to and worked with many people, some of whom did have past, present, or suspected ties to the Communists. Therefore, he was suspect in an age that was paranoid. Martin’s views on the Vietnam War also made him suspect.

For now, I’ll just say that J Edgar Hoover never turned up any more evidence of Communism than what I have just told you. It is true that some of the files are still under court seal until 2027. But some have been released, and you can bet that if Hoover had had better evidence, he would have said so.

The question of adultery is more difficult and also more relevant in an episode on Coretta. At the time, the only accusations of sexual misconduct came from the FBI, who had explicit instructions to get dirt. Not to find out if there was dirt. Just to get it. To me, this is not a reputable source. It was only many years later, decades after Martin’s death, that some who knew him, including women, admitted that there was some adultery going on, though I would not describe any of the credible claims as a “hideous abnormality.” Many of the accusations are so ridiculously over the top, I reject them out of hand. But because of those claims, decades later, there are some people who do believe that Martin was not faithful to Coretta.

It is sad, but true, that all of history’s heros turn out to be more complicated than we would like. On my show alone, there’s been Gandhi and Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin and others. But if this was Martin Luther King Jr’s personal failing, then I will say this for him: He could have caved in the face of the pressure the FBI placed on him. He did not. He didn’t let it stop his work on behalf of peace and equality. He kept going for the rest of his life.

Coretta also kept going. I can’t say for sure what she knew in her heart. But she kept going on the marriage and in the movement for the rest of her life.

The Assassination and the Aftermath

On April 4, 1968, Coretta was at home with her children when she received the call saying Martin had been shot in Memphis and his condition was serious. She headed to the airport, but she received the news that Martin had died before she even boarded her plane (King, My Life with Martin Luther King Jr, 318-319).

Coretta returned home to tell her children. She went to Memphis the following day to claim Martin’s body.

In the very month of Martin’s death, Coretta filled in for Martin at rallies and events in Memphis and New York. (McCarty, 59). In one of these, Coretta ended by quoting a poem by the great African American poet, Langston Hughes. The poem is called “Mother to Son.”

Well, son, I’ll tell you:

Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.

It’s had tacks in it,

And splinters,

And boards torn up,

And places with no carpet on the floor —

Bare.

But all the time

I’se been a-climbin’ on,

And reachin’ landin’s,

And turnin’ corners,

And sometimes goin’ in the dark

Where there ain’t been no light.

So boy,

Don’t you set down on the steps

‘Cause you finds it’s kinder hard.

Don’t you stop now —

For I’se still goin’, honey,

I’se still climbin’,

And life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.

Coretta concluded her speech saying:

With this determination, with this faith, we will be able to create new homes, new communities, new cities, a new nation. Yea, a new world, which we desperately need!” (King, Coretta, 10 Commandments)

Life for Coretta was also no crystal stair. But she was climbing. In June of the same year, she announced the creation of the King Center, an organization that promoted Nonviolent Social Change. She had chosen to start a new organization, rather than try to fit herself into those Martin had worked in. She also wrote a memoir, which became a bestseller and allowed her to support her family.

Coretta traveled around the world, speaking, giving concerts, and fund raising for the King Center. She served on the commission for presidential elections and sponsored oral history projects. In 1977, she was a presidentially appointed delegate to the UN. I am giving you only a small smattering of what she did. There’s lots more. It’s an incredible list.

The Legacy

What’s also incredible is how much America changed during her lifetime. It is certainly true that race relations in the US continue to be less than perfect. But I attended public schools with fellow students of all races who got the same education I did. I currently live in a mixed race neighborhood, where one of the nicest houses on the street is owned by a family with a white mother and a Black father. I, a pasty white person, have made music under black conductors, attended church meetings organized and directed by black leaders, sent my child to school to learn from black teachers. None of this would have possible in the country Coretta grew up in. I stress again that I’m aware that we haven’t achieved perfection. My own city proves that on a regular basis. But we are better. And we’re better largely because of the bravery of people like Coretta and Martin.

As regards the holiday, Coretta lobbied for it for almost two decades. The idea was first introduced only four days after Martin’s death. John Conyers, a Democrat from Michigan introduced the proposed bill in Congress, but it went nowhere. The idea was raised and promoted again and again. In 1982, she teamed up with Stevie Wonder to collect 6,000,000 signatures in support of the holiday. John Conyers was still around, and he said:

“I have never viewed it as an isolated piece of legislation to honor one man. Rather I have always viewed it as an indication of the commitment of the house and the nation to the dream of Dr. King. When we pass this legislation, we should signal our commitment to the realization of full employment, world peace, and freedom for all” (McCarty, 70).

The measure passed in Congress. President Ronald Reagan signed it into law on November 2, 1983 (McCarty, 70). We still celebrate it every January.

Coretta continued to travel, speak, and organize for decades more. She died on January 30, 2006.