The most surprising thing about the bicycle is that it wasn’t invented earlier. The wheel has been around since at least 4000 BCE (arguments on that date abound). As a machine, the bicycle is no more complicated than many things the ancient world built, or at least it doesn’t have to be more complicated. And as a transportation device, a bicycle is unparalleled. On average, you can move four times faster on a bike than on foot while still burning five times less energy (Rosen, “Introduction”). A bicycle is cheaper to buy and maintain than a car or a horse. It’s easier to store than either. It’s easier to operate than either, though I might not have believed you when I was first learning.

But even with all these clear advantages, bicycles are relative latecomers in the history of human invention. Maybe because materials that were both strong and lightweight were in short supply. Maybe because it wasn’t at all obvious that a two-wheeled contraption could possibly balance, and to be honest, I still don’t understand how it does.

The Bicycle in Development

For whatever reason, it was not until 1817 that Karl von Drais of Baden in what is now Germany created a two-wheeled, one-person vehicle, which he called a Laufmachine or “running machine.” Other people called it a velocipede or a dandy horse.

Von Drais’s velocipede is recognizable as a bicycle, but it was far from perfect. It was heavy, as it was made of wood and iron. Also it had no pedals. You pushed yourself along with your feet on the ground, much like a balance bike for kids today.

The velocipede was briefly in vogue among the young, rich, and well-dressed. Or in other words, the dandies, which is why it got the name dandy horse. That wasn’t meant as a compliment. By 1818, London ladies had the option to buy a version meant for women. Unlike the men’s version, it didn’t require lifting your leg and a heavy skirt over the bar, because it had a stepthrough frame. How many women actually did this, I don’t know, but the device was for sale. We have the ad:

Whether male or female, the riders of the velocipede so terrorized the unsuspecting pedestrians that its use was banned in at least three countries (Rosen, “Introduction”) and that was the end of that. The idea of a self-propelled, two-wheeled vehicle seemed destined for the dustheap of history.

Until the 1860s, when several French inventors added pedals. This sparked a new craze among the trendy. The French still called it a velocipede. English-speakers called it a bone-shaker, which tells you everything you need to know about how it felt to ride one. This was partly because few roads were smooth, but also because the tires were not inflatable, so they didn’t absorb much of the shock.

Also, there were no gears or chains attached, which meant you got a 1:1 ratio between how much you pedaled and how much the wheel turned. This is a serious limitation. You just don’t go that far or that fast. For reference sake, the modern bike has a 3:1 ratio (Crawford). But the gear and chain solution was still to come.

The solution in the 1870’s was to make the front wheel very, very big. A big wheel turned no quicker than before, but its size meant that it traveled a good long distance for the same amount of rotation. Sounds good, but it came with some serious downsides. That enormous wheel meant that it was difficult to mount the thing. It required acrobatic balance while in motion. And it was very, very easy to dismount, at least by way of flying straight over the handlebars. Not kidding. This penny farthing, as it came to be known, was a dangerous machine (Harmond, 236-237).

Mark Twain learned to ride the penny farthing in 1886. He wrote an essay on his experience learning to ride it, and in the end, he was in favor. His conclusion was: “Get a bicycle. You will not regret it, if you live” (Twain).

Like most dangerous machines, the penny farthing was viewed as the province of men. You can argue about whether women were kept out, or whether they just weren’t that stupid. But certainly women were not the target market.

The Safety Bicycle

The breakthroughs came in the 1880s. A variety of inventors added inflatable tires, which cushioned the ride, and the chain drive, which allowed you to get more wheel turn for the same amount of pedaling. This meant the size of the front wheel could come back down to reasonable levels (Crawford). The resulting invention looked and functioned more or less like a modern bicycle, and its name was reassuring: it was called the safety bicycle.

The world took note. The US, for example, had 150,000 bicycle riders in the year 1890. By 1893, we had one million. By 1896, we had four million (Harmond, 239-240). I don’t have statistics for other countries, but the craze was not limited to the US. Europe was enthralled with bicycles too. This reach was possible because a bike was relatively cheap. At the time, a horse cost about $150 dollars, plus $25 per month for upkeep. A bicycle could be had for only about $50 or even less, and it didn’t need to be fed or stabled (Harmond, 244-245; Sears).

It was enormously popular, and it was no longer limited to men. Because it was safe. With a name like the safety bicycle how could it not be?

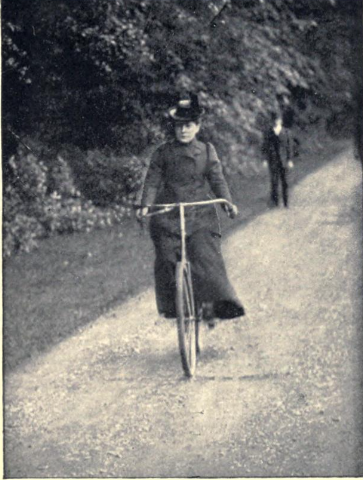

It wasn’t just the very young who learned either. Frances Willard was 53 when she first mounted the silent steed, and she later wrote a book about it. She ran through multiple teachers and multiple falls before she “finally concluded that all failure was from a wobbling will rather than a wobbling wheel” (Willard 26). She mastered that bicycle and ended her book with a moral: “Go thou and do likewise!” (Willard, 75). Pictures from Willard’s book are below:

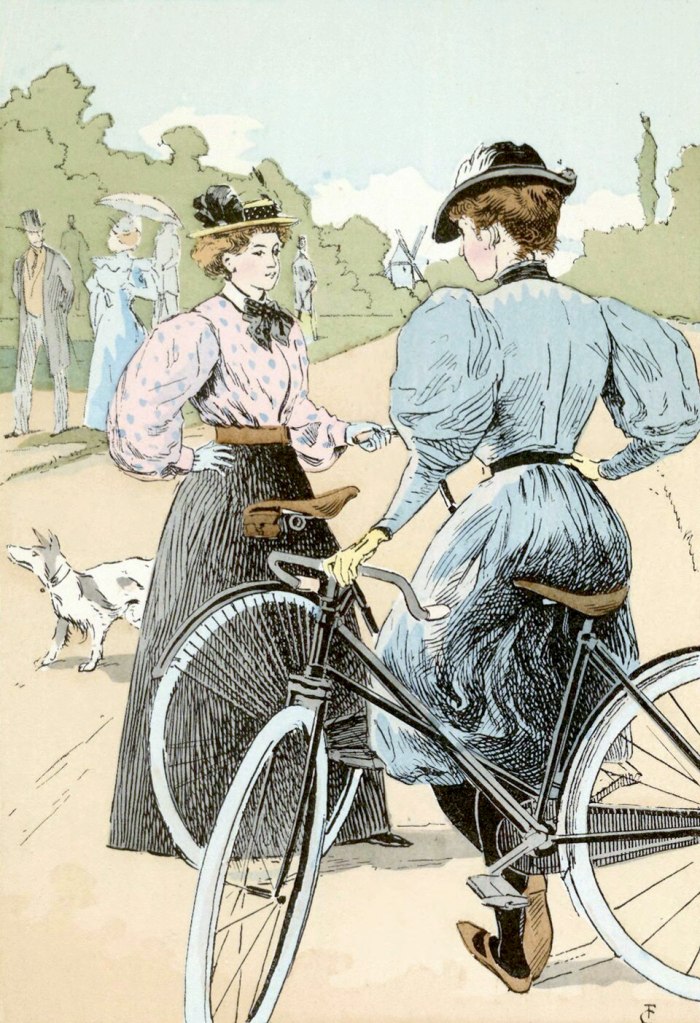

In retrospect, I’m a little surprised that cycling was so readily adopted by women. It could so easily have remained in the category of “things not appropriate for the female sex”. But there were several major groups who ensured that its success.

Promoted by Manufacturers, Advertisers, the Health Conscious, and the Romantic

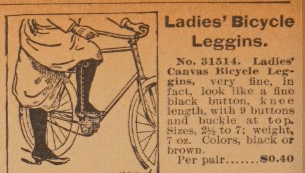

One group was the manufacturers and advertisers. Why limit yourself to just men, when you can get women’s money too? The 1897 Sears Roebuck catalogue sold not just the lady’s bikes (Sears, 613), but also lady’s bicycle shoes, bicycle gloves, bicycle tights, bicycle leggings, fabric for homemade bicycle suits, and attachable child seats. Those are just the items meant to appeal to women specifically. Of course, there were all manner of bicycle lights, bicycle horns, bicycle tire pumps, bicycle lubricating oil, and bicycle repair kits that were bought by both men and women.

One of the industry magnates was so excited about selling to women that he sponsored a woman named Annie Londonderry to bicycle around the world as a publicity stunt. She did cycle around the world. Sort of. I have bonus episode on Annie’s story.

Another group that supported women on wheels were the health conscious. Or at least the majority of the health conscious (more about that later). Times had changed since the Jane Austen days when “taking a turn about the room” was considered adequate exercise for a genteel woman. A growing number of men and women now spent their days in sedentary indoor pursuits. Sedentary, by their standards, that is. My life is far more sedentary, but let’s not talk about that. Anyway, cycling got you getting exercise out in the fresh air and many people now believed that was a very good idea (Harmond, 243-244; Willard, 53-56).

The romantics were not averse either. Because there were tandem bicycles and even a bike called the sociable, where two riders pedaled side-by-side. Not a bad date activity, huh? There was even a hit song about it, called “Daisy Bell,” but better known as “A Bicycle Built for Two.” In 1894, this song was recorded by the Edison Phonograph Company on a wax cylinder, which allows me to bring you a chorus which thrilled the hearts of women 130 years ago:

In case you’d like a less scratchy version, here it is again by yours truly:

Women and Mobility before the Bicycle

The feminists were very excited by the possibilities of women on bicycles. Apart from just wanting to be included in new trends, the feminists spotted one very important feature of the bicycle that the original inventors or manufacturers did not necessarily intend: it liberated women in particular.

For many of us in our modern age, it’s a little hard to fathom just how limited mobility was for most of history. If I need to go to work, run an errand, visit a friend, or get out of my house for a while, I just hop in my car and do it. But that’s not how it was for most women in history because transportation is a privilege. Jobs, errands, friends, and escapes generally had to be within walking distance, which seriously limits your options.

Sure, there were horses and sometimes other animals to ride or drive. But even if your family owned a horse, it probably didn’t belong to the women of the house. Even if you got permission from the man of the house, you probably could not hitch up the horses yourself. That was a man’s job, and girls frequently weren’t taught. Even if you got that sorted, there was the question of safety and propriety. To go anywhere without a chaperone was forbidden to certain classes of women, especially if you happened to be young and single. The barriers here are piling up, and the plain fact of the matter is that most women lived lives that were narrow in geographical scope, and also in social and educational scope. All justified on the theory that this kept women safe. Which is a dubious claim since domestic violence is a thing.

Women and Mobility After the Bicycle

No one originally thought the bicycle was a threat to a system that limited mobility (and therefore opportunities) for women. And at the beginning, it wasn’t a threat. Bicycle magazines included articles on making sure the chaperones also knew how to ride (Neejer, 301). But that was doomed to failure because girls on wheels were leaving chaperones in the dust. It was even a subject of humor. One magazine published this fictional dialogue:

‘I thought I saw you riding alone with a gentlemen last evening.’

‘You did.’

‘But does your mother let you go bicycling with gentlemen without a chaperone?’

‘No, indeed.’

‘But you had none.’

‘Oh, we had one when we started out, but we punctured her tire to get rid of her.’ (Neejer, 305)

This was not published in some risqué magazine. It was in a mainstream pub, read by respectable people. If this was humor, it was light. The infraction was not serious. The girls’ honor or virtue or whatever you want to call it was not damaged beyond repair.

For many women, this wasn’t about going out with a man. It was about going out alone. One rider said “the bicycle is always ready when the woman feels like riding. It requires nobody to harness it, and nobody else to go along” (Neejer, 306).

By 1898, Vogue magazine declared the chaperone eliminated (Neejer, 311). Women on wheels had chipped away at the idea that public spaces were meant for men by cycling themselves there and insisting on their right to stay. Alone. Or with friends their own age. Or with a man. Whatever.

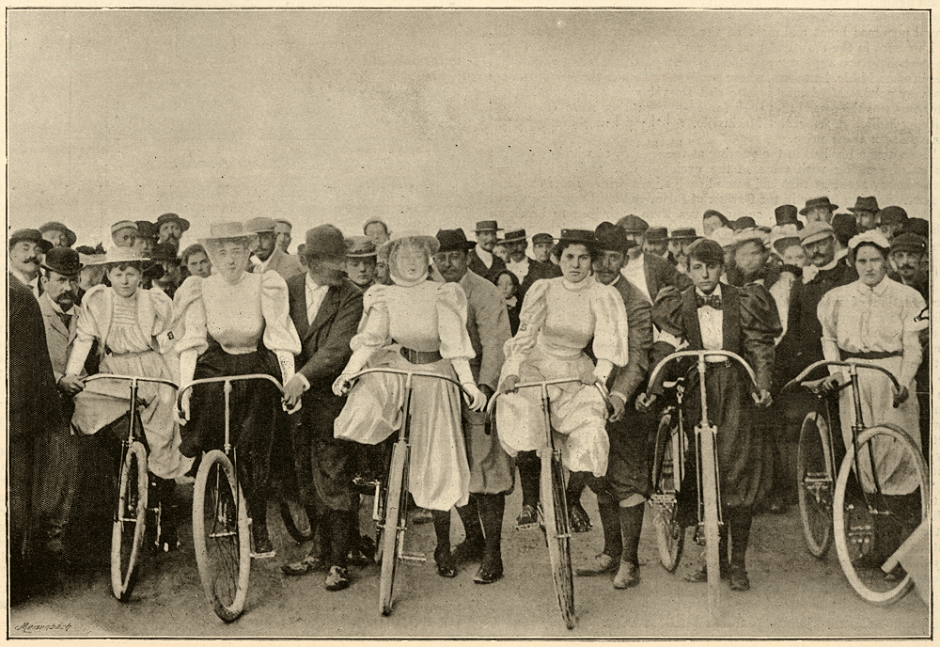

Feminists were not slow in noticing this new freedom. As early as 1892, one woman commented that “women speakers have been agitating for fifty years on the emancipation of the sex by law and statue, and the bicycle has done it without aid from either” (Neejer, 312). Another speaker said “Women shut in for generations, even for centuries, in narrowed environments, hot-house atmospheres, bound body and soul… saw their way out through the means of the bicycle… they took swift advantage of it, regardless of the means employed, and as a result we had thousands of women, flying, dashing, reeling, wobbling and sprawling over our streets and parks, mounted upon anything having wheels” (Neejer, 314)

Susan B Anthony was a little old for a bicycle. She was in her seventies by the time the safety bicycle was commercially available, but she admired it all the same and said “a girl never looks so independent, so much as if she felt as good as a boy, as on her wheel” (Neejer, 317). She was, in Susan’s words, “the picture of free, untrammeled womanhood” (Weber).

Opposition to the Bicycle

So far you might be getting the idea that everyone loved seeing idea of women on wheels. But this is not the case. Change never happens without opposition. Some segments of the population were utterly horrified, and their complaints were loud and wide ranging and somewhat hysterical.

For example, in 1896, the Wichita Kansas daily newspaper printed a sad tale about a young married couple named Mr. and Mrs. Dennison, who started out so happy.

“Then, in an evil hour, Mr. Dennison presented his wife with a bicycle… Mr. Dennison says that his wife developed the bicycle fever to such a degree that she neglected everything—her home, her children, and her husband… Since then, she says, her husband has treated her cruelly, so that she was finally compelled to leave him. Now she has commenced a suit for separation on the grounds of cruelty. Mr. Dennison contends that his wife is a bicycle fiend, and offers, with proof, the following letter, which she recently sent to him: My Dear Husband—Meet me on the corner of Third Street and Seventh Avenue and bring with you my black bloomers, my oil can, and my bicycle wrench” (Rosen, chapter 5).

That letter sounds more like a plea for roadside assistance than proof of fiendishness, but this was not the only divorce blamed on the bicycle.

/im

In New York, two girls dressed themselves as men, rode bicycles to a neighboring town, and got themselves jobs as waiters. When they were found out, their father said, “I lay this to the bicycle craze. Both girls insisted on having bicycles and then got to bloomers. Finally, they have adopted male attire entirely” (Rosen, chapter 5). It seems not to have occurred to him that that maybe what they wanted was a paying job.

Rev. Thomas B. Gregory of Chicago blamed the bicycle for pretty much everything. It was a “menace to the mind” that “annihilates the reading habit.” It causes “heart disease, kidney affections, consumption, and all sorts of nervous disorders.” It destroys the homes as the children lie abandoned while the parents go cycling. “It makes women immodest. And when a woman throws off the beautiful reserve which the Almighty has placed around her she stands on dangerous ground. There is no telling what a woman will do after she has lost her womanliness” (Rosen, chapter 5).

It wasn’t only the clergy who worried about the bicycle causing sexual misbehavior. More than one medical journal printed warnings about the effect of a bicycle saddle’s friction rubbing against certain portions of a woman’s anatomy and the feelings this would engender. The Medical World printed the words “It is a dreadful thing to think that the first thing that should render a young and pure girl conscious of her sexual formation would be her first ride on a bicycle. God save our girls, and keep them pure and virtuous!” (Rosen, chapter 5). It seems to me that maybe these male doctors were the ones who were overly conscious of a girl’s sexual formation, but no doubt they felt pure and virtuous themselves.

Such hysteria was more or less ignored by the women on bicycles. An article in a magazine is pretty ignorable.

What was far less ignorable was the very real harassment out on the streets. In Cambridge, England, students hung an effigy of a woman on a bicycle to protest the proposal of granting university degrees to women (Waite). As early as 1888, boys in city parks are reported to have thrown debris into bicycle wheels to make the woman riding fall. A crowd of bays or men could push a woman on a bicycle into the gutter. Shouted obscenities were common. Carriage drivers would suddenly swerve to cut them off. That harassment was no joke, and some of it was less about the bicycle than it was about the clothes.

The Bicycle and Bloomers

Forty years before, women’s rights activists like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton tried to change the norms on women’s dress by wearing bloomers. They failed, and all of them gave it up. Not because they changed their minds about its value, but because it was impossible. Women in bloomers were yelled at, whistled at, touched without their consent, surrounded, hit by rocks, and even arrested.

You can hear bitter memories of this in Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s speech on the bicycle. After settling the question of whether women should ride (and her answer is yes), she moves on to what women will wear, and she says:

This too with their usual good sense, they will decide for themselves, by finding what is best adapted to the new situation… They will, as an object lesson, illustrate a great natural law, that woman is a bifurcated animal, & does not run as she seems to the ordinary observer, like a churn on castors, a pyramid in shape from waist downwards. A being with two legs, in free motion, must of necessity have bifurcated garments. This revelation of legs has been a great shock to some sensitive souls, & the debates on the question what women should wear have been as hysterical, as in the first point, should she be permitted to ride at all. As she decided the first for herself, & defiantly rode off in the face of her opponents, so she will decide the second point, & wear what she pleases

(Stanton).

The fact that harassment was so common was in and of itself a reason to argue against women cycling. It really was dangerous! As had been true for millennia and to some extent still is, it was still easier to say women should just stay home than it was to say men should just behave themselves. Then it wouldn’t be dangerous.

However, the New Woman was having none of that. Recommended strategies for dealing with harassers included carrying ammonia syringes, or guns, or even bicycle wrenches, which after dark could be mistaken for a gun (Neejer, 90-91).

Many women also clung to their skirts. Or at least minimally modified skirts (Neejer, 79). Not because all of them wanted to. But because they realized that looking respectable lessened the chance of harassment. Frances Willard, age 53, recommended skirts three inches from the ground and walking shoes with gaiters, a costume to which “no person of common sense could take exception” (Willard, 74).

Over time, the bicycle played a significant role not only in changing perceptions about where a woman could go, but also what a woman could wear. The plain fact of the matter was that cycling was difficult in long skirts and tight-fitting bodices. As more and more women adopted more and more alternatives, it became less shocking. Even normal. Boys didn’t even look up when a woman whizzed by. It was a victory that Susan B Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton did live to see, which may have been a small comfort for not living to see women get the vote.

The Bicycle Today

To this day, millions of women use the bicycle every day for transport and for pleasure. But it is true that the craze died down in the United States. That’s largely because in 1908, the first model T Ford rolled off the assembly line, and for the bicycle enthusiast it was all uphill from there.

Of course, cars affected bicycle use elsewhere too. But nowhere as dramatically as in the Ford’s home country, which was young enough, big enough, spread out enough, rich enough, and blithely dismissive of genuine ecological concerns enough for cars to eclipse the bicycle. In countries that are smaller, denser, poorer, or more concerned about the environment, the bicycle continues to flourish.

The social impact of the bicycle is still with us. In a great many (but not all) countries, women like me appear in public spaces without a chaperone and wearing bifurcated clothes, if we so choose.

Selected Sources

Crawford, Jason. “Why Did We Wait So Long for the Bicycle?” The Roots of Progress, July 13, 2019. https://blog.rootsofprogress.org/why-did-we-wait-so-long-for-the-bicycle.

Harmond, Richard. “Progress and Flight: An Interpretation of the American Cycle Craze of the 1890s.” Journal of Social History 5, no. 2 (1971): 235–57. https://doi.org/10.2307/3786413.

Neejer, Christine. “The Bicycle Girls: American Wheelwomen and Everyday Activism in the Late Nineteenth Century.” Dissertation, 2016. file:///J:/Other%20computers/My%20Laptop/Podcast/15%20Inventions%20That%20Changed%20Women’s%20Lives/15.2%20Bicycle/Neejer_grad.msu_0128D_14614_OBJ.pdf.

Rosen, Jody. Two Wheels Good. Crown, 2023.

Sears, Roebuck Catalogue, 1897 Edition. Sears Roebuck, 1897. https://archive.org/details/1897searsroebuck0000unse/page/30/mode/2up?view=theater.

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady. Elizabeth Cady Stanton Papers: Speeches and Writings, -1902; Articles; Undated; “Shall Women Ride the Bicycle?” undated. – 1902, 1848. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mss412100053/.

Twain, Mark. “‘Taming the Bicycle,’” 1886. https://719ride.com/wp-content/uploads/taming-the-bicycle-mark-twain.pdf.

Waite, Katherine. “From the Archive: Cycling to Equality | British Online Archives.” British Online Archives, 2022. https://britishonlinearchives.com/posts/category/articles/509/from-the-archive-cycling-to-equality.

Weber, Bruce. “Overlooked No More: Annie Londonderry, Who Traveled the World by Bicycle.” The New York Times, November 6, 2019, sec. Obituaries. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/06/obituaries/annie-londonderry-overlooked.html.

Willard, Frances Elizabeth. A Wheel within a Wheel: How I Learned to Ride the Bicycle. New York: Fleming H Revell Company, 1895. https://archive.org/details/wheelwithinwheel00williala/page/n7/mode/2up?view=theater.

[…] you were so lucky as to be a very rich women, then you were determined not be left out. The bicycle (ep. 15.2) had already made serious inroads on the old idea that women could not be out and about in public […]

LikeLike

[…] Mary was adventurous as a middle-aged woman, she could learn to ride a bike to get around town or to destinations more […]

LikeLike