The current series is Inventions that Changed Women’s Lives and today’s episode was suggested by listener Mary. Mary’s idea was excellent, and it’s a very important topic in history. But it’s also a hot topic politically, and I have a strict no-modern-politics policy on this show. There are approximately 4.61 million other podcasts you can go to for that. What I’m going for here is to give you the historical background. Assuming you’re okay with that, here we go:

In the first century CE, in the city of Rome, a girl named Soteris was buried, and her marker said:

“Lo, under this marker are placed the bones of Soteris; she lies buried, devoured by pitiless death. She had not yet filled up twice three years when she was bidden to enter the house of black Dis [god of the underworld]. The lamentations which the mother ought to have bequeathed to her daughter, these the daughter suddenly bequeathed to her mother.”

This epitaph does not mention the method by which pitiless death devoured Soteris, age five.

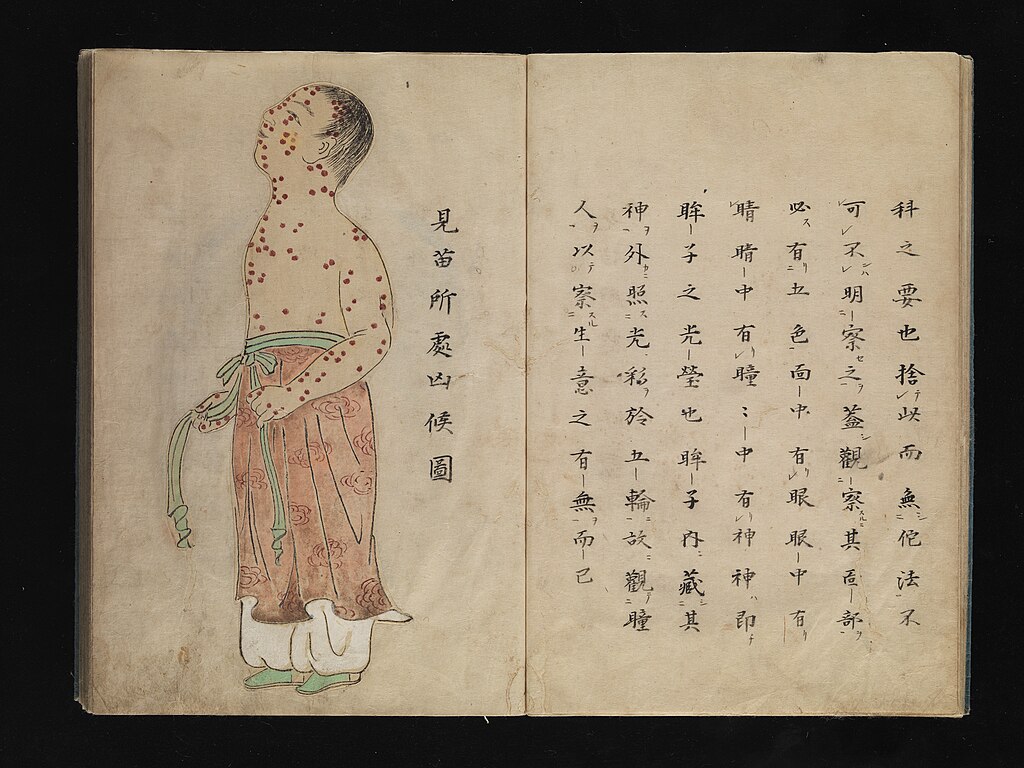

It could have been smallpox, which causes a severe headache, followed by back pain, fever, nausea, weakness, and then blisters all over the body. Those who survived generally carried pock marks for life, but they were the lucky ones. Thirty percent of sufferers died (Isaacs, 26).

Or it could have been pertussis, which looks like a common cold at first, but eventually progresses to a cough so loud it was called whooping cough. It often triggers vomiting. And death (Kinch, 200).

Or diphtheria, which used to be called “the scourge of childhood.” In diphtheria, a thick membrane grows over the child’s throat so that they gasp for air until they finally choke to death (Isaacs, 111-112).

Or measles, which is stunningly contagious, more so than any of the others I’m mentioning. It causes high fever, red or brown bumps on the skin, and similar bumps on your internal surfaces, which can lead to brain damage, blindness, susceptibility to other infections, and death (Kinch, 223).

Or polio, which was terrifying because it might kill your child, or it might just leave them paralyzed for life, and you wouldn’t even know when it was traveling through your area because most people carrying it show no symptoms at all.

Soteris may have died from any of dozens of other options. The list of possibilities is long. All of these diseases could and did kill large numbers of children in every society where they existed, which was most of them. Estimates on how many children died are hard to calculate because records are sketchy, but my various sources estimate anywhere from 10% to 50%. And those are just averages. That means many mothers were even more unlucky. Some lost more than half their children. In the modern world, that would be unimaginable.

It’s rare for us to have any surviving words about a child who died in the ancient world, and rarer still for those words to mention the grief of the mother. But there were untold millions like Soteris’s mother. They risked their lives in pregnancy, gave their love and labor to an infant, watched that infant grow, and then buried that child. Again and again and again.

Modern people sometimes marvel that historic women had so many children. There are multiple reasons for that, but surely one of those reasons was that you knew some of them would die. Having wealth and power was no protection.

Even the lucky mothers, who had multiple children survive, spent days and weeks and maybe years of their lives caring for desperately sick children because all children were desperately sick multiple times. It was an unavoidable part of growing up. Dealing with it was an unavoidable part of motherhood.

Searching for a Solution

It took humanity a very long time to figure out any effective solution to this. Thucydides, writing in the 5th century BCE, recognized two basic features of these diseases: First, anyone who survives is unlikely to get the same infection again. Second, anyone who does get infected a second time will have a much milder form of the disease (Isaacs, 15). Thucydides explained this based on personal experience with the Plague of Athens. We don’t know exactly which disease that was, but we do know that it killed about 25% of all Athenians, and the city never really recovered as a major power.

Thucydides was not the only person to notice those two basic disease features. It was well known, and at some point, some anonymous person in Asia took the audacious next logical step: If you deliberately infect people with a mild form of the disease, they are then safe from the dangerous form of the disease. This is called variolation. (It’s not yet vaccination.) We have records of variolation for smallpox starting in 9th century China. It was downright common by 16th century China (Isaacs, 34).

The tricky part, of course, is where do you get a mild form of the disease? With smallpox it was possible, partly because it was certain to come around every few years, partly because its virulent form was extremely dangerous, and partly because smallpox does have a mild form, which is unlikely to kill anyone. Assuming you have correctly identified someone with the mild form, you can collect the pus and particles from their blisters and inhale it. Or just open a vein and push the stuff in. Disgusting, I know. But it was nothing compared with the agony of experiencing the virulent form of smallpox.

Variolation was done in scattered pockets across Asia for centuries, but Europe largely did not know about it. You might expect that some man of science brought it to Europe’s attention. But you’d be wrong.

Lady Mary Brings the Solution to Europe

Lady Mary Pierrepont was born in London in 1689. She later described sneaking away from her governess to enter her family’s extensive library so she could ‘steal’ her education. Clearly, she didn’t think much of the education her governess was offering. At age 23, Mary eloped and became famous as Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. She was highly regarded as beautiful, charming, witty, and extremely helpful to her husband’s political prospects. However, in 1713 her brother died of smallpox. In 1715, she caught it herself. She lived, but she bore the pockmarks, and she lost her eyebrows.

Eyebrows might seem like a small price to pay for your life, but this was bigger than eyebrows. Political careers could be made or broken by the charms of the wife as hostess. More than one person assumed that Lady Mary’s scars meant the end of her husband’s success. According to one contemporary observer, Wortley was “inconsolable for the disappointment this gives him in the career he had chalked out of his fortunes” (Barnes, 342).

I am not sure if his next move was a promotion or a demotion, but within months, the family was sailing away from English shores. Wortley had been made ambassador to Constantinople.

Lady Mary’s adventures in the East should be their own episode, so today I will just say that she was primed to pay attention when she became aware that Turkish women did not fear smallpox the way English women did. They didn’t have to because they variolated their children. Lady Mary pondered this, looked at the results, and hired a woman to variolate her son. She was not the first European to do this, but she was the first one who wrote home about it to a readership that adored her witty style and circulated her words among the British upper class.

Her fans continued to adore her when the family returned to England. When smallpox broke out again in 1721, Lady Mary asked a prominent doctor to variolate her daughter, who had been too young for it in Turkey. Dr. Maitland agreed to do it only if three members of the College of Physicians came as witnesses. Which meant it was now a public event.

Lady Mary also convinced a good friend of hers to give it some thought. The good friend was Caroline, Princess of Wales, wife of the Crown Prince. Caroline wanted a little more evidence, and she sponsored a trial on volunteers from Newgate Prison. Inmates scheduled for execution were promised their lives and their freedom if they agreed to participate. Modern ethics committees would never approve this, but there were no ethics committees, and all went well, even when one of the women was sent to care for people with smallpox. Caroline was convinced. She had the royal children variolated.

Because of Lady Mary and Princess Caroline, large swathes of the English upper class protected their children from smallpox.

Early Hesitancy

The opposition to smallpox variolation (of course there was opposition) came from the medical establishment. They did not like being upstaged by a couple of society dames, and some of them said so. Here’s a quote:

“Posterity perhaps will scarcely be brought to believe, that a method practiced only by a few Ignorant Women, amongst an illiterate and unthinking People, shou’d on a sudden, and upon slender Experience, so far obtain in one of the most Learned and Polite Nations in the World, as to be receiv’d into the Royal Palace” (Dr. William Wagstaffe, June 1722, quoted in Barnes, 349).

Okay, so misogyny aside, the racist problems is: what counts as experience? This method was not untested. The experience was slender in Europe, but it had been practiced by thousands and maybe millions of people in Asia.

This is not to say that it was 100% safe. You might be mistaken about a mild versus virulent form. And not everyone reacts the same. Some people did die from variolation. But not as many as died from smallpox.

Debate raged about whether this was a good idea, but two who sincerely regretted not doing it were Benjamin and Deborah Franklin (episode 14.7). Their son Franky died of smallpox, and Ben would later write saying

“I long regretted bitterly, and still regret that I had not given it to him by inoculation. This I mention for the sake of parents who omit that operation, on the supposition that they should never forgive themselves if a child died under it; my example showing that the regret may be the same either way, and that, therefore, the safer should be chosen” (Stuart, 35; Franklin, chapter 10).

Another person who heard and considered the English adoption of variolation was Catherine the Great of Russia (episode 2.5). Catherine believed in science, education, and reform. She knew that wealth and power was no defense against disease, and she had good reason to be concerned. In 1767, smallpox came to St Petersburg. She later wrote “I fled from house to house, and I banished myself from the city for five whole months, not wanting to put myself or my son at risk” (Ward, 8).

Her son, the crown prince, was not pleased, nor had he been pleased by this kind of protection for some time. At age twelve, he wrote that he was forbidden to go to a masquerade because “there is a great monster called Smallpox, walking up and down the ballroom. This same monster has very good foreknowledge of my movements for he is generally to be found in precisely those places where I have the most inclination to go” (Ward, 95).

Of course, Paul was a lucky one. The sons of poor mothers had no ability to flee from house to house. They just stayed where they were and died.

In June 1768, Catherine decided that the situation was unsustainable. She told her ambassador in England to hire an English doctor who could be trusted to variolate the Russian prince, as the British royal children had been. To forestall anyone who might say she was exposing her son to unnecessary risk, she decided to be variolated herself. She was the only sitting monarch to take it quite that far (Ward, 2). When all went well, she set up multiple facilities to do the same for her people (Ward, 209).

Medical statistics was still in its infancy, but there’s enough data from St Petersburg to know that three in every thousand children variolated died of the procedure. Which sounds bad. But the rate of death in the St Petersburg Smallpox Hospital, which treated unvariolated children was 57 times higher (Ward, 212). Smallpox was a fact of life and there is simply no question that it was safer to variolate than to not variolate.

Jenner and the Smallpox Vaccine

Variolation went out of favor before the end of the century because vaccination was much, much safer. In 1796, Dr. Edward Jenner realized that milkmaids did not seem much troubled by smallpox, and this was because they all got the annoying, but survivable, cowpox within a few weeks of becoming milkmaids. Cowpox came from milking the cows, and it produced scabs that looked very much like smallpox scabs. But they only affected hands and occasionally arms. No one fell sick. No one died. The scabs went away, leaving a milkmaid who was protected for the rest of her life.

There were still no ethics committees, so Jenner collected pus from the hands of milkmaid Sarah Nelmes, and he injected it into the veins of a small boy whose father worked for Jenner. The boy was then deliberately exposed to smallpox, and he did not get sick. Jenner was not actually the first person in Europe to do this, but he was the one who published it, got his paper translated into six languages, and disseminated the idea through the Western world (Isaacs, 44). The very word “vaccinate” comes from vaca, Latin for cow, because it was specific to using cowpox to protect against smallpox.

Variolation was more of a risk because it was actual smallpox. And you might be wrong about how mild it was. Nevertheless, many people were bitterly opposed to vaccination too. It was primarily educated and powerful people who promoted it, which meant the poorer classes were suspicious, especially when it was accompanied by a mandate (Isaacs, 48). Some clergy thought it violated God’s will. Some people were justifiably concerned about how cowpox was cultured and spread in a world without refrigeration or modern chemical procedures. You might not be injecting just cowpox into your child. A host of other infections could come too (Isaacs, 48).

On the other hand, none of those infections were likely to be as dangerous as smallpox. And procedures got better over time. They got immensely better.

So there was good news on the smallpox front, but what about all the other contagious diseases that killed children? Jenner’s vaccine did nothing against those.

Pasteur and the Proliferation of Vaccines

Louis Pasteur was the first scientist to discover that even if a disease did not have a mild form or variant, there was a way to create one. A sample of bacteria or virus can be weakened with heat or chemicals. It still prompts the human immune response, and then you’re protected. Pasteur did this first in animal populations with a variety of diseases that took down a farmer’s herds and flocks. But he also developed a rabies vaccine for humans (Isaacs, 68).

Once it was understood that this was possible, the scientific methods started to catch up with the hopes and dreams of mothers since prehistory. There was no need for so many children to die from childhood diseases.

In 1896, there was a typhoid fever vaccine, and this one was the best one yet because it was an inactivated vaccine, meaning that it was not a live infection. It could not cause the disease it protected you from, not even a mild form of it. But it still worked. That would become the new standard.

The cholera vaccine came just afterwards, in the same year. Then bubonic plague in 1897, tuberculosis in 1921, diphtheria in 1923, tetanus in 1925, pertussis in the 1930s, yellow fever in 1937, polio in 1955, measles by 1960, mumps and rubella in the 60s, meningitis, hepatitis, and pneumonia in the 80s, and safer and improved versions of all of the above, plus more diseases right on through the present day (Montero).

It is because of vaccinations that we now live in a world where most of us have never experienced any of these diseases. This would be unthinkable to any mother who lived before the mid-20th century. We now give birth expecting that our kids will live to adulthood. We expect that any childhood illnesses will be relatively minor and quickly over. Sometimes we are wrong about that, and that’s tragic. But for most of my listeners, if that happens to you, it probably won’t be because a contagion whipped through your neighborhood and took 30% of the children with it. Multiple times.

A Threat Still at Large

However, that does not mean that these diseases are no longer a threat anywhere. They’re still out there. Whooping cough still kills 170,000 children every year (National Foundation). Measles kills 140,000 children every year (Unicef). Several thousand more die or are paralyzed by diphtheria and polio every year (Wu, Ochman). Once again, I’m skipping over dozens of other diseases that also kill thousands of children every year.

Only one of all the diseases I’ve mentioned has ceased to exist in the wild, and that’s the big one we started with. Smallpox was declared eradicated on May 8, 1980. This is truly one of the great triumphs of humanity, and it was accomplished by the World Health Organization tracking down every last case and vaccinating every last person who came into contact with the virus.

The very last person to die of smallpox was Janet Parker of Birmingham, England, in 1978. Her case sparked a panic because smallpox was already eradicated in the UK. No one expected the last case of smallpox to occur in a first world country. I have a bonus episode on Janet’s story, available for subscribers on Patreon or Into History, and also for individual purchase on Patreon.

Only two years later, the global eradication of smallpox was complete, which is why we no longer bother with smallpox vaccines. I’m happy to say you don’t need Jenner’s great invention.

Unfortunately, smallpox was unique. Among other things, it was only carried by humans. Not animals. That’s not true for most of the other diseases. As hard as it was to vaccinate every last human on the planet, imagine how hard it would be to vaccinate every last rat. Or every last bird. Or every last mosquito. It just can’t be done.

Smallpox is gone, but the other diseases continue to circulate, and they move very quickly in an increasingly globalized world. Yes, antibiotics are another fabulous invention to be covered in a future episode, but they don’t solve everything. Antibiotics were available to Janet Parker. She died anyway.

If you liked this article, please consider supporting the show, either with a one-time donation or as a regular subscriber with benefits like ad-free episodes and bonus episodes.

Selected Sources

Barnes, Diana. “The Public Life of a Woman of Wit and Quality: Lady Mary Wortley Montagu and the Vogue for Smallpox Inoculation.” Feminist Studies 38, no. 2 (2012): 330–62. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23269190.

Campbell, Elisabeth, and Matthew Roller. “Soteris – JHU Archaeological Museum.” JHU Archaeological Museum, June 4, 2021. https://archaeologicalmuseum.jhu.edu/staff-projects/latin-funerary-inscriptions/epitaphs-for-children/soteris/.

Franklin, Benjamin . “The Project Gutenberg EBook of ‘Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin.’” Gutenberg.org, 2019. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/20203/20203-h/20203-h.htm.

Gearon, Eamonn. “Who Was Lady Mary Wortley Montagu?” National Trust, n.d. https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/discover/history/people/who-was-lady-mary-wortley-montagu.

Isaacs, David. Defeating the Ministers of Death : The Compelling History of Vaccination. Sydney, New South Wales ; New York, Ny, Usa: Harpercollinspublishers, 2019.

Kinch, Michael. Between Hope and Fear: A History of Human Vaccines and Human Immunity. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

Montero DA, Vidal RM, Velasco J, Carreño LJ, Torres JP, Benachi O MA, Tovar-Rosero YY, Oñate AA, O’Ryan M. “Two centuries of vaccination: historical and conceptual approach and future perspectives.” Front Public Health. 2024 Jan 9;11:1326154. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1326154. PMID: 38264254; PMCID: PMC10803505.

National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. “Whooping Cough (Pertussis).” https://www.nfid.org/, April 2021. https://www.nfid.org/infectious-disease/whooping-cough/.

Ochmann, Sophie, Max Roser, Saloni Dattani, and Fiona Spooner. “Polio.” Our World in Data. Global Change Data Lab, November 9, 2017. https://ourworldindata.org/polio.

Stuart, Nancy Rubin. Poor Richard’s Women : Deborah Read Franklin and the Other Women behind the Founding Father. Boston: Beacon Press, 2022.

Unicef. “More than 140,000 Die from Measles as Cases Surge Worldwide.” http://www.unicef.org, 2019. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/more-140000-die-measles-cases-surge-worldwide.

Ward, Lucy. The Empress and the English Doctor. Simon and Schuster, 2022.

Wu, Zilun, Liyu Lin, Jinbu Zhang, Jirui Zhong, and Donglan Lai. “Global Burden of Diphtheria, 1990–2021: A 204-Country Analysis of Socioeconomic Inequality Based on SDI and DTP3 Vaccination Differences before and after the COVID-19 Pandemic (GBD 2021).” Frontiers in Public Health 13 (June 20, 2025). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1597076.

[…] children began having children of their own, they were born into a very different world. One where vaccines were increasingly available, and it improved the child fatality rate. One where doctors were told to wash their hands and it […]

LikeLike