The first question is: Do you even need a product to manage your period?

Many of you, like me, will answer that with a resounding “Yes!” But history is full of women who would not agree with us.

Free Bleeding and Other Early Options

We have almost zero records on this for ancient women, but surely the oldest way to manage your period is to do nothing. It’s called free bleeding. You might drip. You might stain.

In the modern world, this is a problem because we sit on upholstered chairs, walk on carpeted surfaces, wear clothes that should look like we just bought them, believe in the value of hygiene, and most of all must always appear as though we are not menstruating, even when we are.

These are cultural practices. They are not inherent in the condition of being female.

If you spent most of your time outside or on a rush floor that was intended to get dirty and be replaced, if chairs were either nonexistent or hard and wipeable, if there were no shame attached either for menstruating or for having a bright red spot on your dress, if you spent your menstruation days in the company of other women who were also menstruating, that might change things. Hygiene remains an issue, but standards vary on that too.

Depending on the culture, menstruation was sometimes seen as a wonderful thing. Why hide it in disgust when you can celebrate it?

Among the Beng people of the Ivory Coast, menstruating women are known to be the best cooks, but only other women are supposed to eat the food they cook. Other cultures believed menstrual blood to have magical powers or menstruating women were thought to be lucky for the whole tribe (Clancy, 26-7 7).

The details vary, but the one thing that remains the same is that I am given no information on what products, if any, these women used to manage or collect the flow.

Even so, the oldest recorded product that I know of is really, really old. Medical texts from ancient Egypt mention inserting various materials into the vagina, possibly for the purpose of staunching blood, which might or might not mean menstrual blood. Translations are tricky (Nathan), but it’s often thought to be the first mention of a tampon.

But whatever those Egyptian scribes were describing, my guess is that if they troubled to write it down at all, a whole lot of women were already doing something similar on their own brain power and initiative. And if they thought of tampons, it seems likely that they thought about rags and wadding outside the body too. In other words, they used a pad or sanitary napkin.

Unfortunately, the scribes were mostly men and they mostly didn’t concern themselves with daily concerns men don’t have to deal with, we are now going to skip lightly over millennia of lived experience across all continents, until we get to a more modern era of European and North American history. Sorry about that, but it’s all I’ve got.

The 19th Century

So we’ve now arrived at an era when women wore layers and layers of petticoats. That was a pain in many ways. But one advantage that it did have was that you could hope any stains would not travel as far as the outer layer.

You may have noticed that we have arrived at concealment as the cultural expectation.

Exactly how we got there is hard to say. Even my best and most scholarly source says it’s because of the Bible, where Eve ate the forbidden apple in the garden of Eden, and so God cursed her with menstruation. The only trouble with that theory is that the Bible doesn’t say any such thing. The book of Genesis clearly states that Eve’s curse was pain in childbirth. That chapter doesn’t even mention menstruation. I’m not sure how old this misreading is, but it’s old.

Later on in Leviticus 15, there are fourteen verses on just how unclean menstruating women are, and how everything she touches is unclean, and so on and so forth. You might wonder how a young Jewish or Christian girl is supposed to feel about being “sick of the flowers” which is the terminology that the King James Bible uses. But even this isn’t as misogynistic as it sounds here in isolation. The previous eighteen verses specify exactly the same thing for males and any ejaculations they might have. There is no trace of embarrassment on either side. If you can pull away from the shaming involved in our modern Western culture, the whole chapter seems less about shame than it is about hygiene. Basically, it says if your body is emitting something, then wash yourselves and the clothes. I don’t have a problem with that message.

But whatever the reason, by the modern period of European history, menstruating was now bad and shameful. You should hide it. Or at least you should try to hide it. I can only imagine that a woman’s ability to do that was pretty limited when she lived in a one-room house with a limited wardrobe, owned very few clothes, and had no municipal trash removal.

To the extent that women managed this at all, they did it by making their own napkins out of rags. This was work, but it had the advantage of being customizable to whatever size, shape, and thickness suited you. The other way you managed this was by saying you were ill and going to bed, presumably on sheets that were already stained anyway. Of course, some women do really feel like trash during their periods, and that’s legitimate. But it’s also true that many a male doctor in the 19th century mandated this as good healthy behavior, whether you actually felt like trash or not.

I am not kidding on this. The most egregious example was a little book published in 1873, which said Sex in Education: Or a Fair Chance for Girls. With a title like that, you might think the author was advocating for giving girls an education. But no. His basic concept was that the body has limited energy. That energy can’t go to the brain and to other parts of the body at the same time. Therefore, neither girl nor woman can be educated while menstruating. She must lie down, rest, and focus on menstruating. Otherwise, she will damage her vital reproductive organs and will lose her “fair chance” at reproducing (Vostral, 28).

Feminists cried foul, but the book still went through seventeen editions in thirteen years (Vostral, 27). It was a hit.

Naturally, this go-lie-down idea worked for a certain social class. Somehow, nobody worried about the health of poor girls and women who kept right on working during this time. If such a woman did stay abed, she was accused of “playing the lady.” Obviously, this suggests that the poor woman’s complaints were a lie, but it equally suggests that the rich woman’s complaints were also a lie. Either way it had no compassion for women who really felt terrible. It also had no recognition that some women felt fine but went to bed anyway, either because their doctor told them to or because they struggled to manage and conceal the blood. This last continues to be a problem for girls and women around the world, which is why one of the options on my November poll for a Her Half of History donation is to Days for Girls, a charity which helps girls get access to period products, so they don’t have to interrupt their education or their livelihood for lack of access. If you’re listening to this in November 2025, and you haven’t voted in the poll yet, go vote!

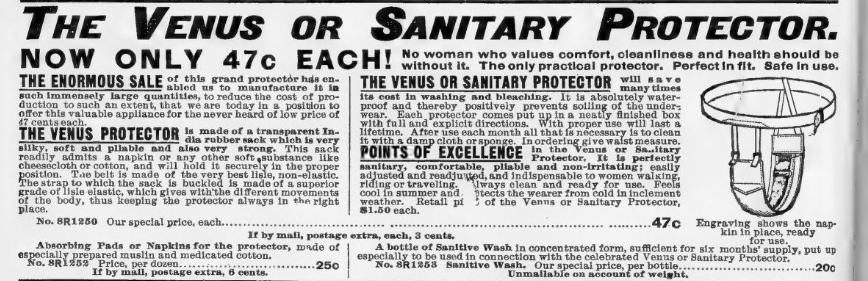

Anyway, back to the subject at hand, effective period management was about to see innovations. When Sears Roebuck began carrying pre-packaged pads in the 1890s, they were not very successful (Vostral, 5). But in general, they were on to something. The necessary product supply chain and sale networks now existed. There were public health initiatives about raising the standards of hygiene. There were girls and women entering the business world, whether it be in a factory or an office. Your boss (almost certainly a man) was probably not going to be sympathetic about monthly time off or a trail of blood. These women could no longer conceal it by staying in bed, or at least at home.

Another factor (which surprised me when I read about it) was that women were simply menstruating more. A declining birth rate meant that your average woman spent less time being pregnant and therefore more time menstruating over a lifetime (Vostral, 24).

Sanitary Napkins in the 20th Century

Kimberley-Clark was the innovating company that would usher in a new era for menstruating women. They made various cotton and paper products, and they were the ones who noticed that the absorbent bandages they had produced to help World War I soldiers were being co-opted by World War I nurses for quite a different purpose (Vostral, 65).

When the war was over, there wasn’t as much call for bandages, but they were easily repackaged and officially rebranded. Kimberley-Clark’s Kotex sanitary napkins hit the market in 1920 and were the first successful commercial period product. Their ads in the Ladies’ Home Journal were designed to be elegant, discreet, and tasteful. The ads also said that Kotex was cheap, but it wasn’t. At 5 or even 10 cents, just one pad cost as much as a loaf of bread. Women paid up anyway (Vostral, 66).

Initially, the plain blue box and a name like Kotex meant you could ask for it without embarrassment and carry it home without shame. That was part of the appeal. Remember, self-serve shopping and store-provided plastic bags were not yet a thing. You had to ask the store clerk to get it for you. But Kotex became such a raging success that it was no longer private. Everyone knew what was going on if you asked for Kotex.

Johnson and Johnson saw this as an opportunity. When they brought out their version, it was called Modess, which could have meant anything. And they also sent you coupons in the mail, so you could just discreetly hand it to the store clerk and avoid actually saying anything out loud (Vostral, 68).

Notice how menstruating is now so shameful that we can’t even admit that we might bleed at some point in the future.

Johnson and Johnson knew that Kotex had a stranglehold on the market, so they also hired efficiency expert Lillian Gilbreth to do market research on exactly what women wanted from their period products and how they could do it better.

Her report, dated January 1, 1927, is the first wide survey of menstruation ever, giving us the kind of details we can really only guess at for earlier generations.

Gilbreth collected responses from over 1,000 women of various ages and locations. Her results indicated a potentially huge market just waiting to be served.

For example, she found that girls living at home still made their own napkins. They didn’t start buying commercial products until they went to college or were businesswomen who had no time, space, or materials to make their own. Only 16% of respondents said they were satisfied with their current napkin. Kotex, for all its market dominance, women found Kotex too large, too long, too wide, too thick, and too stiff (Bullough, 620).

It was Gilbreth’s report that finally made it clear to me that I had entirely missed one important point because I was too locked in the present. It turns out that my mental image of a sanitary napkin was entirely wrong for this era. A modern pad has adhesive on the bottom, and it sticks to your underwear until you cleanly pull it off and throw it away. Kotex was designed to be thrown away. However, that adhesive was an invention in and of itself, and it didn’t exist yet. Even if it had existed, it wouldn’t have helped these women because it only works if your underwear fits snugly around you. That happens with elastic, which had been invented, but wasn’t yet common in clothing. A pad that adhered to your loosely fitting underwear would not have worked well at all.

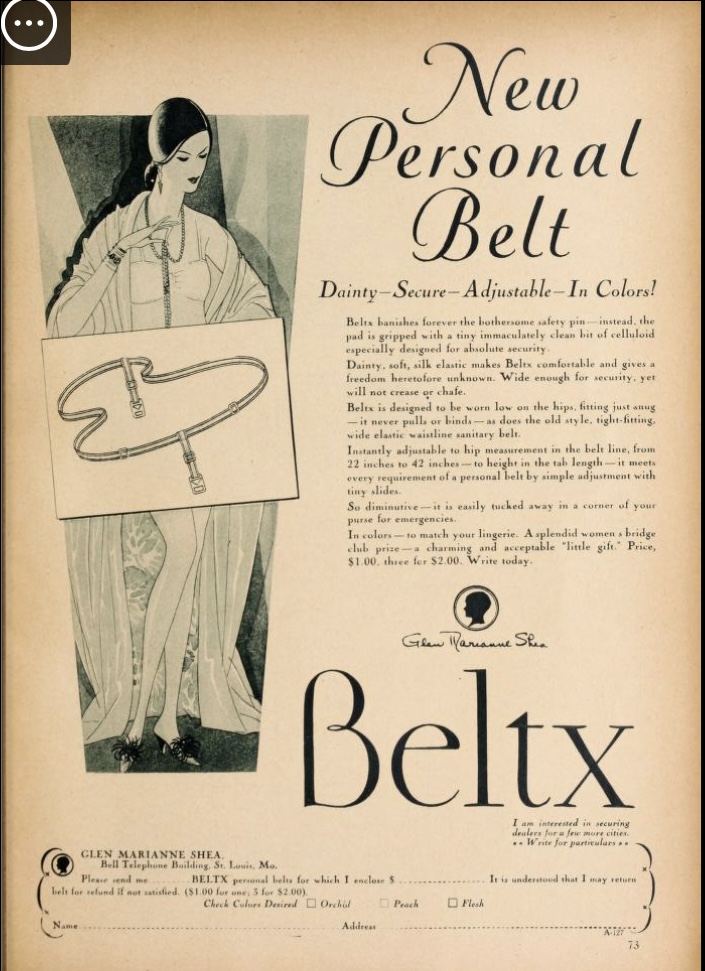

With no adhesive and no elastic (and in earlier eras, no underwear), women fixed that pad in place with a sanitary belt. You tied, clasped, or buckled that belt around your waist and your pad has tabs long enough to pin, clasp or tie onto the belt, front and back. That’s how it stays in place (Bullough, 625). The sticky adhesives that are used today were not introduced until 1970 (Renault).

Gilbreth reported that what the belt looked like was totally irrelevant. What women wanted was comfort and a pad that stayed in place.

Gilbreth also noted a lot of accessories, from rubber bloomers, which she does not recommend, to powders and deodorants on which she is neutral, to vaseline and cold cream which she does recommend as good on the edges of the napkin to prevent chafing (Bullough, 626).

One final point: the official instructions on Kotex said that it was flushable. You were supposed to take your used pad, disassemble it, soak the bloody parts, and then flush them. Gilbreth’s research proved that even reading those instruments was too much work, and women who actually followed them when the plumber proved that not only was she menstruating, but she had also caused an expensive repair bill (Vostral, 72).

Obviously, there was plenty of room for product improvement, not the least of which was in the instructions and in the introduction of trash cans in all women’s bathrooms. Because even in 2025, it’s still not a good idea to flush a pad.

Gilbreth’s report was extremely helpful, both to Johnson and Johnson and to historians. But in 1927, all makers of all sanitary pads were about to see competition from an entirely different product: the tampon.

The Tampon in the 20th Century

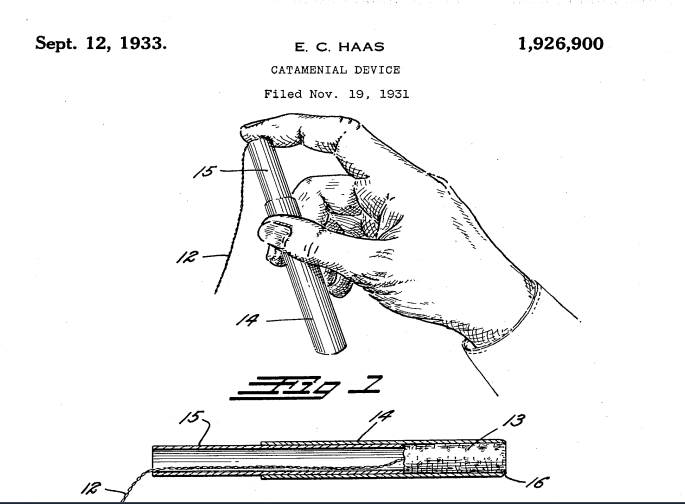

The idea was not new, as I said before. We have no way of knowing how many historical women had contrived something of the sort and were brave enough to insert it. Between 1890 and 1921, a number of patents were filed, but they weren’t intended for menstruation. They were for surgery or other major medical issues. The line between them and pessaries used for birth control was blurry, and therefore it was more or less hush-hush, and maybe illegal (Vostral, 76).

Between 1927 and 1931, several people thought of using this idea for more regular monthly use. The one who succeeded in bringing it to market was Earle Cleveland Haas, who named it Tampax. His version expanded lengthwise but also came with a cardboard dispenser. His wife tested all the iterations, and he eventually sold the rights for a flat $32,000 and no further royalties because he was done, done, done thinking about menstruation. “I didnt want anything to do with it,” he said. “I was so sick of it. After a while you get turned off on those things, boy” (Vostral, 78). Yes, well, him and a whole lot of women who also don’t want to think about it but don’t find it so easy to stop.

Anyway, by 1940 women’s magazines were flooded with Tampax ads and the main selling point was that it made menstruation even more invisible: less risk of bleeding through, less risk of getting dislodged, less outline of a pad visible through your dress.

The Other Options

Pads and tampons were (and are) the most common period products used, but there are other options. The menstrual cup was invented far earlier than I expected. There’s an 1867 patent for a rubber sack to be inserted in the vagina (Renault), but getting a patent is one thing. Getting your product mass-produced, distributed, sold, and most-of-all used, is something else again. I’m not aware that this version of the menstrual cup went any further than the patent office. In 1937, the actress Leona Chalmers invented it again and brought it to market. She had competition from a couple of others. During World War II, a shortage of latex rubber meant the product could go no further, but it came back in the 50s (Renault).

Commercially-speaking, however, the menstrual cup faced a big disadvantage: customers only bought it once. Yep, the very thing that made it more environmental was also the thing that made it less commercial. Companies found it hard to make a profit, therefore the advertising budget went down, and they found it still harder to make a profit. It all but disappeared for a couple of decades and then reappeared in 1987. Use of cups has grown but they remain far less popular than either pads or tampons.

A more recent innovation is period clothing. Beginning in the 1990s, you could buy underwear, and then swimsuits, leggings, and whatever with special moisture wicking cloth which could capture the blood in and of itself (Meltzer). In a way, this was not a new idea at all, right? It’s basically free bleeding. Let it flow, count on your clothes to handle it. The difference is that you can be far, far more sure that it won’t soak through to the outside of the clothing. It’ll stay inside until you run it through a washing machine.

Truly, modern technology is a miracle, and it’s just one of the many reasons I’m glad I live in the modern world, not the historical one.

This week I have a special thank you to Timothy who made a one-time donation online and Margaret who signed up as a new Patreon supporter. If you can be as fabulous as Timothy and Margaret, please visit Patreon or Buy Me a Coffee. If it’s still November 2025 when you read this, half of your donation will be going to a nonprofit, and please don’t forget to vote for which one!

Selected Sources

Blakemore, Erin. “A Glimpse at Women’s Periods in the Roaring Twenties.” JSTOR Daily, March 22, 2019. https://daily.jstor.org/a-glimpse-at-womens-periods-in-the-roaring-twenties/.

Bullough, Vern L. “Merchandising the Sanitary Napkin: Lillian Gilbreth’s 1927 Survey.” Signs 10, no. 3 (1985): 615–27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3174280.

Clancy, Kate. Period. Princeton University Press, 2023.

Meltzer, Marisa. “Go with the Flow: How Period Clothing Went Mainstream.” the Guardian, November 5, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/nov/05/go-with-the-flow-how-period-clothing-went-mainstream.

Nathan, Smiti. “Did Ancient Egyptians Use Tampons? – Dr. Smiti Nathan.” Dr. Smiti Nathan, September 30, 2024. https://smitinathan.com/did-ancient-egyptians-use-tampons/.

Renault, Marion. “Menstrual Cups Were Invented in 1867. What Took Them so Long to Gain Popularity?” Popular Science, August 23, 2019. https://www.popsci.com/menstrual-cups-history-period-care/.

Smithsonian. “Feminine Hygiene Products.” Smithsonian Institution, n.d. https://www.si.edu/spotlight/health-hygiene-and-beauty/feminine-hygiene-products.

Victoria and Albert Museum. “Sanitary Suspenders to Mooncups: A Brief History of Menstrual Products · V&A.” V&A, 2023. https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/a-brief-history-of-menstrual-products?srsltid=AfmBOopbKW7RUhtNsYVcU_NZK5J-AALKWhLJ_xHGgTLXPJNHXrkHYrWG.

Vostral, Sharra Louise. Under Wraps : A History of Menstrual Hygiene Technology. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2008.