Santa Claus has reinvented himself many times over the centuries. He’s been everything from a 4th century Turkish bishop named Nicholas, to an Anglo-Saxon rogue named Yule, to a Dutch-American elfin creature named Sinterklaas, to an English bearded man named Father Christmas. Over the 19th century, he slowly began to take on his modern appearance as Santa, at least in English-speaking countries.

1850s

We’re going to begin our century of letters in the 1850s, when Santa had arrived, but he wasn’t yet the kind of jolly man who would be delighted to accept your order. His letters were actually going the other way around. He sometimes left a letter for the children.

Two of those children were Charley and Erny Longfellow, the sons of the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Henry is famous in America for making Paul Revere famous, but he was not responsible for the letters Charley and Erny received at Christmas in 1853. Those came straight from Santa, care of their mother, Fanny Longfellow. Santa at this point favored honesty over tact, and he was brutal. He said “I wish I could say you have been as good boys this year as the last. You have not been so obedient and gentle and kind and loving to your parents and little sister as I like to have you and you have picked up some naughty words which I hope you will throw away” (Longfellow).

No word on whether the Longfellow boys took this lesson to heart or not.

These boys received their mail at the fireplace of their own home. It did not come through the regular postal service. That would have required a trip to town to the post office or another public place. Nobody had yet thought of free home delivery provided by the postal service. The best you could hope for was that maybe a friend or neighbor would pick it up for you. Otherwise, it was pay extra or go get it yourself. In the US, city-dwellers began getting mail at their homes in the 1860s and rural dwellers waited decades longer (Palmer).

Home delivery service made children aware of the mail in a way they hadn’t been before. Also, the price of postage came down, even as service went up. Writing directly to Santa and sending it like a real grown-up person’s letter was the next logical step.

That’s the origin story of letters to Santa in the US. I have a few very brief and not well documented sources that tell me Scottish children shouted their wishes up the chimney, and continental European children left theirs by their shoes, and Latin American children tied theirs to air balloons for the wind to carry to Santa, and children from locations unknown burned their notes because the smoke would fly to the North Pole (Bowler, 71-72; Chronicle Books, 9). Later on children these locations would also mail their letters through the post office, but I have no source that tells me exactly when or how that happened.

1870s

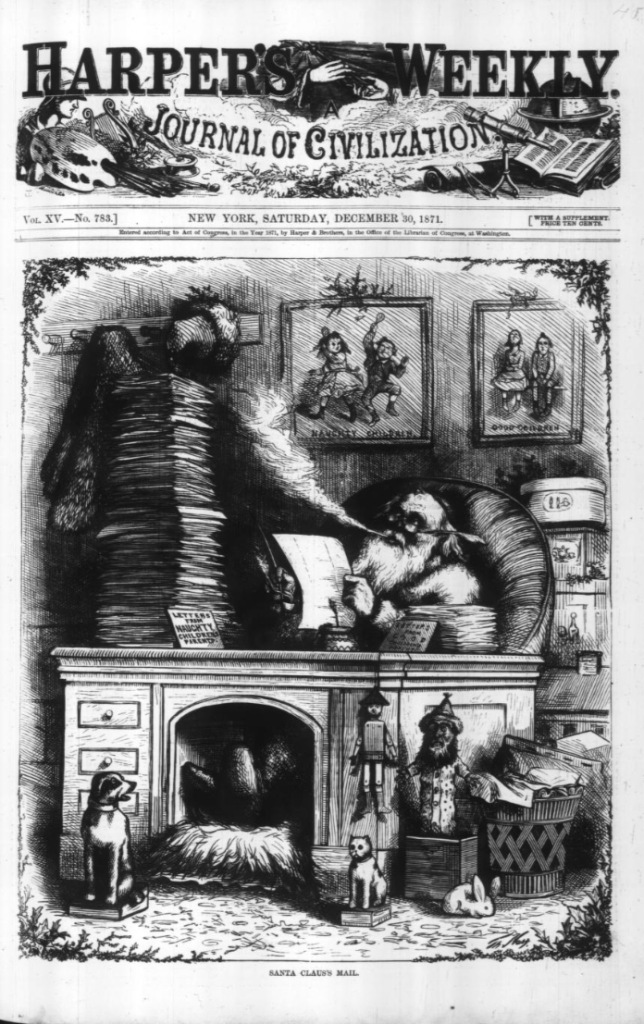

In the US, the idea spread from child to child, but also through popular magazines like Harper’s Weekly. In December 1871, Harper’s Weekly printed a Thomas Nast cartoon of Santa sitting at his desk smoking a pipe and sorting his mail. He’s got a small stack of letters on one side under a picture of good children and a towering stack of letters on the other side under a picture of naughty children. But if you zoom in real close, you can see something that surprised me a little: These letters aren’t from any kind of children. The labels on the stacks clearly state that they letters from good children’s parents and naughty children’s parents.

Later on, the more normal procedure was for the letter to come from the children, even if Mom or Dad helped a bit.

So the letter was written, stamped, and sent out. The only trouble was that not every post office had the North Pole on their regular delivery route. Once the letter was in the postal service’s hands, some overworked mailman had to figure out how to bring it to Santa’s attention. Sometimes they settled on the same method that worked with ordinary people: publish it in a newspaper and hope Santa reads the evening news.

It is because of newspapers that we still can read the words of hopeful children like Maggie, from Hillsboro, Ohio. In 1870, Maggie wrote about new customs that she was only learning about for the first time. Santa had never visited her house before, so she wrote him that “I never hung up my stocking because I didn’t know. Will you excuse it? Please don’t forget to come here this time” (Chronicle, 24).

The letters published in the newspapers spread these children’s wishes, but also the word that it was possible to write to Santa, and you could do it too. Many of the children writing mentioned that they had learned how to address their letter from those same newspapers. Some of the newspapers even instructed the kids to send the letters to Santa Claus, care of the local newspaper office, who would forward it on to Santa after publication (Clark).

1880s

In the 1880s, the letters I have read include some pretty gender-stereotypical requests. Girls mostly wanted dolls and doll accessories, especially doll buggies, which meant a stroller or pram to push the doll around in.

But a girl named Josephine had trickier requests: “Dear Santa Claus” she wrote. “Please bring me a little sister, a dear little puppie. Please let Rosita live together next door to our family” (Chronicle, 23). I surely hope Josephine wasn’t disappointed on Christmas morning.

In one heart-warming letter, Laurinda and her brother Edwin actually sent Santa 50 cents to help him pay for presents for children who had no papa or mama (Chronicle, 28).

1890s

In the 1890s, dolls were still very popular but there were more available, and girls started requesting particular dolls. In 1891 a girl named Zilpah asked for an accordion bisque doll, which sounds oddly specific (Chronicle, 31). Bisque is a type of porcelain, and it was highly prized for high-end dolls in the late 19th century because the finish could look so much like real skin. Of course porcelain is also highly breakable, so it wasn’t a good choice for a very young girl or for a poor girl either. Rag dolls were cheaper and survived better. Affluent girls got the bisque dolls. I have no word on whether Zilpah was one of those affluent girls, but it certainly explains why she wanted one. Where the accordion part comes in, I have no idea.

In 1893, a Welsh girl named Blanche had an entirely different idea. She sent Santa a dress she had made, plus some toys she no longer needed, and asked him to give them away. But she also asked if she could come and watch him distribute them (Chronicle, 38). Again, no word on whether Blanche’s hopes came true.

Other girls in the 1890s were dreaming of luxuries that were unavailable to previous generations. The banana was a tropical fruit that hit the more northerly markets largely in the 1890s. In 1899, one little girl asked Santa for a lot of bananas because she could eat a dozen bananas right now (Tennessee Historical Society). Oranges and nuts were also popular and remained popular for decades.

1900s

When the 20th century opened, the sheer number of letters explodes. Writing to Santa was very popular. Dolls were still popular too, and technology advances meant they could have more engaging features. In 1903, a girl with the initials VF wrote “I would like lots of things, but most of all I would like a large doll which will open and shut its eyes and cry when you squeeze it” (Chronicle, 59). Keep an eye on this space because decades later girls were still requesting the same type of doll.

Another type of doll that was gaining traction was the kind that would look like some of these girls actually looked. In 1909, Katie Boyd requested a great many things, including what she called “another Negro doll” for my other dolls are so lonesome by themselves (Tennessee Historical Society).

In 1905, Thelma from Kentucky was both eager to imitate her mother and also to torment her mother. She wrote “I want … little iron so I can iron my dollies clothes and a half dozen cats. Now, dear Santa, I will not ask for any more Mama say six cats will be plenty” (Chronicle, 61).

But there was also a new toy available to ask for. One that was not exactly a doll, but doll adjacent. In 1907, Edith from Oregon asked for a big teddy bear (Chronicle, 64). The teddy bear had only been invented in 1903 to memorialize an incident that happened in 1902. President Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt went on a bear hunt and couldn’t find a single bear. In a bid to help the president, some friends captured an elderly, injured bear and tied him to a tree so that the big famous game hunter could shoot him and leave his hunting trip victorious. Roosevelt did not think this was sporting, and he refused to shoot the bear. It became a political cartoon and then a toy which was called Teddy’s Bear. It was only shortened to teddy bear in late 1906, one year before Edith asked Santa to bring her one (George).

Many girls might have wanted a doll or a teddy bear, but some girls needed more practical gifts. A 1908 letter from Anaheim, California, said “My mother works hard for our living and she doesn’t get much for her washing and I expect nothing for Christmas. I wish you would send me a pair of No. 2 shoes.” Another girl from Los Angeles wrote that same year: “I am afraid you may forget me, like last year when you did not come” (Chronicle, 66). This type of letter will be a recurring theme. At no point has it ever truly gone away.

1910s

In the 1910s, some kids still weren’t necessarily mailing their letters through the actual postal service. They were placing them next to the fireplace where Santa would see them. We know this for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is that occasionally the letter is still there. In 1911, an Irish girl named Hannah wrote to Santa that she wanted a baby doll, a raincoat, a pair of gloves, a toffee apple, a gold penny, a silver sixpence, and a long toffee. She wrote this down and placed it on a small shelf by the fireplace in her house. And it lay there untouched for 100 years until a builder found it while doing some remodeling in 2011 (Irish Central Staff).

Back in America, Santa’s mail volume had gotten so large that in 1912 the postmaster general organized Operation Santa to handle them. This organization still exists and is well worth looking into if you have a moment.

By my very unstatistical sampling, it also seems like the lists of requests are getting longer and more varied. In 1914, a girl named Edna still wanted a doll and a doll buggy, like many girls before her, but she also wanted an automobile, a small water gun, and a train (Chronicle, 81).

In 1916, a Virginia girl named Elise Eppes had a serious list for Santa. She asked for licorice candy, a sled, and crayons. All seems fairly normal to me, assuming you like licorice. But she also asked for a saw, a tool chest, a plow, live plants, vegetable seed, a bottle of peroxide, and a hatchet that is sharp. Quite a girl this. Perhaps these were things she knew her family needed and she was asking on behalf of her parents. But the plow is specifically listed as “a plow for my garden” (Virginia Museum of History and Culture). The other thing that occurs to me is that in December 1916 the United States was not yet in World War I, but Europe most certainly was and they were running out of food. The US push for home gardening to help produce food was only just beginning, but perhaps Elise had heard or seen some of the discussion about it. Or perhaps she was hungry herself. We have no way of knowing.

Other girls absolutely knew what was going on in the world. Sheila, from Victoria, Australia, started her letter to Santa by hoping he was still alive and that the war had not made him any poorer. If it had made him poorer, she volunteered to go without any Christmas presents, so he would have more for the little boys and girls in Europe. Also for the “brave Australia boys in the trenches” only “please don’t send them my dolls, for I don’t think they would care for them. Chocolates and cigarettes are more in their line.” (You really have to wonder how much adult help Sheila was getting with this letter.) She ends with a few requests for herself, just in case Santa is still flush with cash despite the war, and as a postscript she adds “Please notice that my address is the same as last year” (Chronicle, 85).

1920s

In 1920, Isabelle knew what she wanted: “I want every thing to eat and whole lots of it. Candy, oranges, bananas, coconuts, and a big doll that will go to sleep. Now bring me lots to eat for I am hungry” (Thomas).

By the 1920s, this tradition of sending letters to Santa was so strong that the newspapers were overloaded. Once they had printed a few very short letters and everyone had enjoyed it. Now they were printing pages upon pages of letters, and they couldn’t handle it. One newspaper even printed a letter from Santa Claus explaining a change in policy. Santa asked the newspaper editors to rush the letters directly to him upon receipt, rather than holding on to them in order to publish. This would, he said, save him at least a day’s time on each letter, “and with Christmas so near, time is precious” (Clark). And so it was done.

1930s

Catherine, age 9, and writing during the 1930s, asked for warm gloves for herself and shoes, underwear, and stockings for her brothers and sisters. Except for 10-year-old Jimmy, who (in her words) “ain’t so good so if you want you could leave him out.” But the part that is heartbreaking is that “Mama… never wants anything for Christmas,” which was surely not true, but certainly what a poverty-stricken single mother in the Great Depression told her children when they asked (Koch, 4-5). I assume she was single because there is no mention of a father in the letter, even though every other member of the family is listed by name and age.

Hard times were on the minds of other girls as well. Betty Jane asked for a Shirley Temple doll “as my Daddy not working and I will not get nothing for Christmas” (Koch, 13).

1940s

When I got to the 1940s, I expected to find references to World War 2, similar to the ones about World War 1. And there are some, but fewer than I expected. I think it’s because the total sample size available to me is smaller than it was. Newspapers weren’t printing these letters as much, so that was the easiest place to find them.

But after the war, it was time for fun, and letters to Santa were so well established that it wasn’t just children sending them. On December 19, 1947, Barbara Marsh wrote to Santa and asked him to remember the days when he had just met Mrs. Claus. Ah, love! Ain’t it grand! Barbara was (in her words) in a heck of a fix because she didn’t have a man. Her friend Vilma was in the same boat, so could Santa please look around up there and see if there were any spare males that could be given for Christmas. In case there were plenty to choose from, Barbara sent a description of her preferred type (Koch, 17-19). Vilma’s too.

Barbara was young and giddy, but she wasn’t alone. Also in the 40s, a 47-year-old widow asked Santa for a new husband. When her letter was received, it was reported in the newspaper, and Santa was flooded with letters from men volunteering for the job (Koch, 24-25).

In 1949 a girl in Suffolk, England, still wanted a doll with open and shut eyes (Koch, 26).

1950s

In the 1950s, the economics were better than they had been in the 1930s, but not for everyone. Eight-year-old Shyrle wrote to Santa Claus that she needed help because Daddy still doesn’t come home and Mama cries at night when she thinks we are asleep. “We” meant five children, all listed in the letter, but after listing what her four siblings wanted, Shyrle said she didn’t need anything herself but please bring some shoes for her mother, “with the heels on like the other ladies” wear (Koch, 42-43).

In the same decade, a girl called Alana wrote with the most unusual request: it was basically a job application. She volunteered to wrap presents, pack things, keep the reindeer in order, and more. I have a sneaking suspicion that Alana did not get what she wanted for Christmas (Koch, 39). But other 1950s girls did, including a highly prized gift that became available at the end of the decade: a Barbie doll.

Is There a Santa Claus?

At the end of the 1950s, we have completed 100 years of Santa’s mail. But letters to Santa continue to this day. In fact, Santa Claus gets more mail than any other person on earth. Over five million letters every year. To handle the load, he maintains postal offices in Alaska, Finland, Canada, England, and more. You can also, I am told, send him emails and video messages (Chronicle Books, 8), and probably texts.

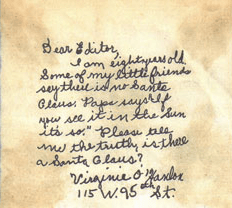

Nevertheless, I am going to end by going back to the year 1897. That September, the offices the New York Sun newspaper received a handwritten letter that was not intended for Santa, but for them, the newspaper editors. It said:

Dear editor,

I am 8 years old. Some of my little friends say there is no Santa Claus. Papa says “If you see it in the Sun, it’s so.” Please tell me the truth, is there a Santa Claus?

Virginia O’Hanlon

The editors of the Sun no doubt enjoyed the testimonial from Virginia’s Papa. In response they printed an editorial that ranks among the most famous writing in the history of American journalism. It was reprinted by multiple newspapers every year for decades. And inspired many other books and movies. I am not going to read you all of the editorial but I will start with the most famous line and carry on from there:

“Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus. He exists as certainly as love and generosity and devotion exist, and you know that they abound and give to your life its highest beauty and joy. Alas! How dreary would be the world if there were no Santa Claus. It would be as dreary as if there were no Virginias. There would be no childlike faith then, no poetry, no romance to make tolerable this existence. We should have no enjoyment, except in sense and sight. The eternal light with which childhood fills the world would be extinguished….

Nobody sees Santa Claus, but that is no sign that there is no Santa Claus. The most real things in the world are those that neither children nor men can see… Nobody can conceive or imagine all the wonders there are unseen and unseeable in the world.”

No matter what you are hoping Santa Claus will bring you this year, or whether you celebrate Christmas at all, I wish all of you the very best this season. Thank you so much for listening.

This week I have a special thank you to Scott who made an one-time donation online and to Margaret who signed up as a new Patreon supporter. If you can be as fabulous as Scott or Margaret, please visit Patreon or Buy Me a Coffee. If you are on the hunt for the perfect gift for someone in your life, be aware that it is possible to gift a Patreon membership. They can get bonus episodes and ad-free episodes. Also don’t forget to vote for the topic of Series 16!

Selected Sources

Bowler, Gerald. Santa Claus. McClelland & Stewart, 2005.

Chronicle Books. Dear Santa: Children’s Christmas Letters and Wish Lists, 1870 – 1920. Chronicle Books, 2015.

Clark, Ben. “Letters to Santa Claus | Marathon County Historical Society.” Marathoncountyhistory.org, 2025. https://www.marathoncountyhistory.org/blog/letters-santa-claus.

George, Alice. “The Teddy Bear Was Once Seen as a Dangerous Influence on Young Children.” Smithsonian Magazine, December 2023. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/history-teddy-bear-once-seen-dangerous-influence-young-children-180983234/.

Irish Central Staff. “When a 105-Year-Old Letter to Santa Claus Was Found in a Dublin Home.” IrishCentral.com. IrishCentral, November 26, 2024. https://www.irishcentral.com/roots/history/santa-claus-letter-found-dublin.

Longfellow, Fanny. “Letter from Santa to Charles & Ernest Longfellow, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1853.” Maine Memory Network, 2025. https://www.mainememory.net/record/148452.

Nast, Thomas. “Harper’s Weekly 1871-12-30: Vol 15 Iss 783.” Internet Archive, December 30, 1871. https://archive.org/details/sim_harpers-weekly_harpers-weekly_1871-12-30_15_783/mode/2up.

National WW1 Museum and Memorial. “Victory Gardens in World War I.” National WWI Museum and Memorial. Accessed November 3, 2025. https://www.theworldwar.org/learn/about-wwi/victory-gardens-world-war-i.

Palmer, Alex. “A Brief History of Sending a Letter to Santa.” Smithsonian Magazine, December 3, 2015. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/brief-history-sending-letter-santa-180957441/.

Tennessee Historical Society. “Letters to Santa Claus, 1895 to 1920 – Tennessee Historical Society.” Tennessee Historical Society, December 18, 2017. https://tennesseehistory.org/letters-santa-claus-1895-1920/.

The Elves (Pat Koch, Head Elf). Letters to Santa Claus. Indiana University Press, 2015.

Thomas, Heather. “Anatomy of a ‘Dear Santa’ Letter | Headlines & Heroes.” The Library of Congress, December 18, 2018. https://blogs.loc.gov/headlinesandheroes/2018/12/anatomy-of-a-dear-santa-letter/.

Virginia Museum of History & Culture. “Letters to Santa.” Virginia Museum of History & Culture, 2025. https://virginiahistory.org/learn/letters-santa.