This episode is a retrospective wrapping up the series Inventions That Changed Women’s Lives.

Without giving away my exact age, I can tell you that I belong to a nebulous generational blip. Depending on what chart you look at, I am either the youngest of the Gen X or the oldest of the Millennials. Or on one memorable chart, I don’t exist at all because there’s a time-sucking void for a few years between those two generations. Or I’m part of a micro-generation that is variously called the Xennials, or the Geriatric Millennials, or the Seasoned Millennials, or Original Millennials™, all depending on which one of those you find funny versus offensive. Personally, I find them all funny.

Anyway, the point is that I remember a time when we survived not just without cell phones, but also without GPS devices, or laptops, or desktops, or Internet of any accessible kind. I remember libraries with card catalogs, asking for directions before going somewhere new, the sizzle and pop of dial-up, and the sweet smell of opening an encyclopedia or a dictionary in print. I remember phone numbers you had to memorize, and answering the phone without knowing who it was calling, and politely asking a friend’s parents if your friend was home because it was a number their whole family shared. I even remember when a home delivery guy showed up at our house and taught us how to put a CD into our very first CD player.

An enormous amount has changed over my lifetime, and many people bemoan how quickly things change and how hard it is to keep up with the latest app or whatever. I am old enough to have sympathy.

But over the course of this series, I noticed something about invention. All of the inventions I just referenced are edging on too recent for me to cover on this show. What I covered was supposed to be older, and it was older. It was also almost all within one historical era. That was not on purpose, but it is what happened. Humanity rolled along for millennia with innovation at a relatively slow, but steady pace. And then something dramatic happened in northern and western Europe and their colonies. It started in the 1760s in Britain, and the next 80 years are generally called the Industrial Revolution. That was very dramatic and it reshaped the world, and it’s worth a full discussion of its own, but even so, I covered only one major invention from that time period: the spinning jenny. That alone was enough to put Britain right at the top of world dominance, and of course they didn’t stop there. The vast majority of the inventions I covered were invented later, in the mid to late 19th century and reached wide markets in the early 20th century. This later period is often called the Second Industrial Revolution, and it’s the one that caught my attention.

A Hypothetical Woman Born in 1860

To illustrate, let’s imagine a hypothetical woman born in 1860. I’m going to call her Mary because that was a popular girl’s name in the United States that year. Please note that there was a lot of disparity across the world. Not everything I’m saying would have applied to Mary if she had been born in a different country. Even so, here we go:

- Mary grew up in a world lit by sunlight, candles, and oil lamps. Maybe gas lamps on the streets if she lived in the right cities.

- If she wanted to go somewhere, she walked. Or if she was lucky, she had an animal to do the walking for her. Maybe she took a train somewhere, but that was for long distances. It didn’t help with the daily business of getting to school, church, or a friend’s house.

- The most universal skill Mary most certainly learned was how to sew. Unless she was very rich, she made most of her own clothes and a good number of her family’s clothes too. Even if she was rich, she did decorative needlework.

- Mary mostly ate locally produced foods in season, which sounds posh now, but at the time meant monotony and possibly some nutrient deficiencies.

- Her career, if she was lucky, was to get married young and start having babies. If the groom did not appear or could not provide, Mary did get a job: probably in domestic service, maybe in a factory, maybe as a freelance seamstress. None of that paid well. In fact, she probably needed additional family support or charity to get by.

- If Mary did have children, there was a fair chance she would bear more children than modern women usually choose to do. There was also a fair chance she would watch some of them die. Assuming she herself survived to see that happen.

- Any children who lived would generate a great deal of laundry which Mary would either have to wash by hand or hire some other woman to wash by hand.

- Those kids would also expect regular meals, which Mary would have to cook or hire some other woman to cook. Either way, it would be done on a cast iron stove which took—I kid you not—a solid hour of daily maintenance. That doesn’t include any of the actual cooking time. Just maintenance: sifting ashes, laying in the fire, tending the fire, emptying ashes, and most of all blackening that cast-iron to keep it from rusting.

- As for education and entertainment. Mary was very privileged to live in an era where it was possible, but not guaranteed, that she was taught to read and there were books, magazines, and newspapers. Whether she could access them is another question, but they existed, and for many women they were the primary source of information.

- Mary could send a letter if she wanted to communicate with someone at a distance. Or maybe—very exciting—she could send a telegram.

But even while she was still a girl, Mary’s life began to take a turn.

- Possibly the first new invention she would have noticed was a sewing machine in her very own home. Sure, she still had to make a lot of clothes, but there’s a fair chance that a machine pushed that needle in and out.

- By the time she was a young woman, maybe starting her own family, she was lighting their evenings with gas lamps, instead of kerosene.

- She might also have begun feeding her family foods that came out of a can, and those didn’t have to be local or in season. Soon she could have ordered some of these goods from a mail-order catalog, even if her local store didn’t stock them.

- Assuming Mary was adventurous as a middle-aged woman, she could learn to ride a bike to get around town or to destinations more distant.

- If she wanted an office job, she could have taken a typing course and learned to type, thus entering a business world that had previously only existed for men. If Mary herself felt too old for these opportunities, she certainly watched her daughters take advantage of them.

- Meanwhile Mary looked on in envy as wealthy women raced by in a cloud of dust, kicked up by the new-fangled automobile. They also communicated by telephone.

- As Mary’s children began having children of their own, they were born into a very different world. One where vaccines were increasingly available, and it improved the child fatality rate. One where doctors were told to wash their hands and it improved the maternal fatality rate. One where women had access to some forms of birth control and water was routinely piped into your very own home, even if you weren’t rich.

- By the time Mary was in her 70s and 80s, the world had flipped over entirely: cars vastly outnumbered horses, ready-made clothes were common, and the lights were electric. Nearly everything in her life would have seemed bizarre and baffling to someone from the year of her birth.

- While it was still common for women to make home and motherhood a career, it was also fairly common for them to spend a few years working in an office or in retail. Domestic service was growing more rare, and even if a woman did clean, cook, or babysit for another woman, she was less and less likely to be a live-in servant. She probably just showed up for regular hours during the day, and then she went home.

- In her own home she cooked on gas or electric stove and stored the ingredients in a fridge. The laundress was a machine, even the machine didn’t belong to her personally.

- If Mary lived to be 99, she even saw the release of the world’s first oral contraceptive. Given her age, it’s entirely possible she didn’t approve, but let’s not just assume that. The women who dreamed up and funded the Pill weren’t that much younger Mary.

Mary may have been pleased with all of these changes, but it’s possible that she said, much like people today, that the world was changing too fast, and she couldn’t keep up, and maybe didn’t want to keep up.

It lines up to be an enormous list of inventions that got rolling in the 1870s, 1880s, and 1890s, and they went mainstream in the early part of the 20th century. Not every woman benefited of course. It depended on your income level and location. But more women benefited than had ever happened in the history of the world before.

So my question is: Why? What was so special about the late 19th century that it saw so many inventions and a Second Industrial Revolution.

They say that necessity is the mother of invention, but honestly, I don’t buy it. The late 19ᵗʰ century certainly needed transport, lighting, clean clothes, healthy food, vaccines, etc., but so did previous generations.

What had changed is that the effects of the First Industrial Revolution had taken hold and restructured society (at least in certain countries). The results picked up steam and charged forward at a speed that astonished all onlookers. In no particular order, here are some of those contributing effects. I make no claims to completeness here. These are just the ones I noticed while researching this series.

Point 1: The Rise of the Middle Class

By the late 19th century, countries like Germany, France, the US, and the UK had a thriving middle class. (This was a direct result of the First Industrial Revolution.) These countries had a poor class too, and I don’t want to trivialize that. But a sizeable and historically surprising number of people in these countries had a roof, clothes, food, and a basic education. And they still had money left over to buy supplies and time to tinker in a backyard workshop on something like a bicycle or a typewriter. That’s where many inventions come from. They don’t come from the poorest of the poor, who are too busy trying to survive. They also don’t come from the richest of the rich, who are too busy enjoying their wealth, and there aren’t very many of them anyway. It’s the middle class who have the resources to get started and still hunger for a better life. Once you reach a critical mass of these people, some of them are bound to get a brilliant idea.

Point 2: A Functioning Patent System

Having a brilliant idea is great, but that’s the easy part of invention. What’s hard is building the prototype, keeping your spirits up when it doesn’t work, fixing all the predictable failures, fixing the second, third, and fourth wave of unpredicted failures, attracting the necessary capital to mass produce, marketing enough to get buyers, and then managing the subsequent business. All of those steps require a completely different skillset than having the brilliant idea in the first place. Almost nobody pushes through all that headache-inducing mess unless they hope to see a financial reward. And that only happens if the legal system will prevent others from looking at your marketing materials, and shortcutting their way to financial success by starting with the work mostly done. By you. Probably with more success than you because they didn’t pay for the research and development, and they only have to be good at the last couple of skillsets.

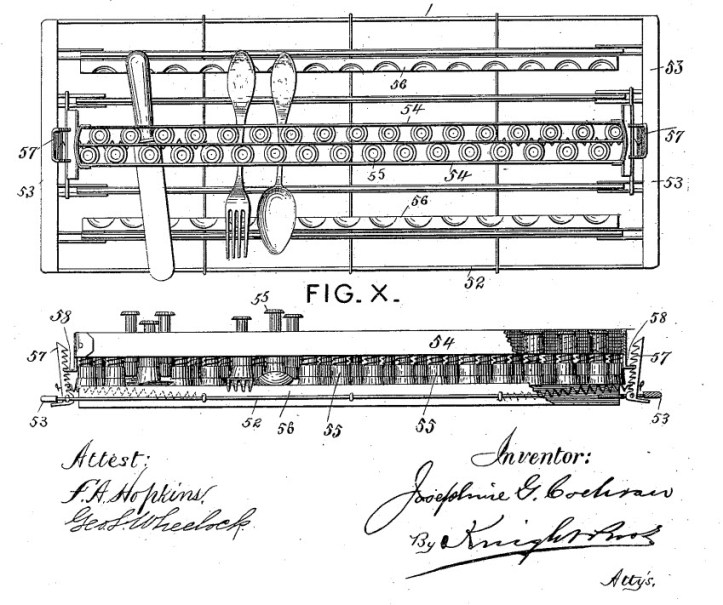

A well-functioning patent system means there’s hope. Not that people don’t steal your idea. They definitely do. But if you own the patent, you can sue. And in multiple cases that’s exactly what happened. This was true for the various inventors of the sewing machine (episode 15.17) and the inventor of the pill dispenser for the oral contraceptive (episode 15.d, available on Patreon).

Germany, the UK, and the US all had a functioning patent system by the late 19th century. That’s what gave multiple inventors the will to keep going.

Point 3: Belief

It may sound wishy-washy, but I think belief may be the most important factor. By the late 19ᵗʰ century, there were living people who had seen how awesome technology could be. They were aware that factory-made thread was both better and cheaper than the thread their great-grandmothers had spun by hand. They were impressed by the speed and power of the railroad. There was a growing belief that technology could make life better and easier.

Sometimes we mistakenly assume that earlier generations didn’t have technology, but only because we are mis-defining the word. The drop spindle was tech, cloth itself was tech, a water-powered grain mill was tech. The pots and pans and needles and thread and soap and all the other work-a-day tools used by women every day for millennia, it’s all tech. It doesn’t grow on trees. Someone had to invent those.

But there wasn’t always a widespread belief that we could quickly improve these and other items in a way that would make a dramatic difference to society at large. And if you’re not looking for small improvements, it’s hardly surprising when you don’t find many.

By the late 19ᵗʰ century, people in the US, the UK, France and Germany were looking with the firm expectation of also finding.

It is not coincidental that this same time period also saw the birth of science fiction. In the 1860s and 1870s, Jules Verne wrote Journey to the Center of the Earth, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas, and Around the World in Eighty Days. In the 1890s, HG Wells wrote the Time Machine, The Invisible Man, and the War of the Worlds in the 1890s. These two authors are just the ones whose novels are still popular in the modern day. They had lots of competitors in their own time. The ideas were in the air, and the expectation was that science and technology were going to make life exciting and fabulous, and they were going to do so soon.

And before you come at me with feminist pickaxes and say Mary Shelley invented sci-fi decades earlier, yes, I know (see episode 6.5). But I also think that the reason she is so often overlooked as the founder of science fiction is that her book did not spark a new publishing genre and inspire hundreds of other authors to write similar things. Frankenstein also wasn’t a novel about how great scientific innovation is. Quite the reverse, in fact.

A Compounding Effect

By the late 19ᵗʰ century all three of those factors were in place: a cultural belief in science and technology’s power, a middle class that had time to tinker and a hunger to sell the results, and a legal system that made it possible.

In my opinion, those factors are the mothers of invention. Not necessity. Necessity is universal. World-changing inventions are not.

And incidentally, all this compounds on itself. The more inventions there are brought to market, the more jobs there are providing more middle-class incomes that produce more middle-class people with time to tinker on still more inventions. Inventions in transportation, communication, and production go on to make it easier for the next crop of inventors to get their goods to market, etc., etc., etc.

It is simply no coincidence that all of the inventors I discussed were almost universally white men from places like the US, the UK, Germany, and France,

Contemporaries noticed this too, and it became the basis for plenty of racism and sexism. The basic argument went something like this: white men from these countries invented all this great stuff so that just proves that white men from these countries are smarter and more capable than everyone else.

To which the answer is a resounding no. Being smart may help you get ideas. But as I said before, ideas are the easy part.

White men from these countries were the ones most likely to be in the middle class. Sure, plenty of white women would also have called themselves middle class, but they were much less likely to be in charge of the family finances. They were given a budget from which they were supposed to handle feminine and household expenses. That budget usually didn’t stretch to things like industrial supplies for your inventors’ workshop out back. If you did stretch it in that direction, your family might reasonably complain that you were doing so at the expense of things like the family food budget.

White men from these countries were also the most likely to work a job from which they could come home and spend their off-hours on personal projects. Women of all colors and locations frequently worked jobs for which there were no off-hours: childcare and housekeeping can both expand to fill every available moment. I am sure many of you know this from personal experience.

White men from these countries were also the ones most likely to bring their prototype to market because they could attract investors, sign contracts, form businesses, and directly market their work. I don’t mean to say that no woman or person of color could do any of that. Some could and some did (Hetty Green, Elizabeth Keckly, Maggie Lena Walker, for example). But it was more likely that a potential investor would turn them down because they considered them a credit risk. Because they were more of a credit risk. That risk was baked into the financial, legal, and social systems surrounding these people.

And speaking of risk baked in, there is finally the point that white men from these countries were most likely to believe not only that technology could advance, but that they personally could be the ones to make it do that. One of the saddest things about telling whole groups of people that they are not as smart, not as capable, not as deserving, not as worthy, is that very often even they believe you.

At this time period, those statements were still mainstream and overt and very widely accepted as God’s own truth. To remind you of just one of many examples, the wildly successful 1873 book Sex in Education: Or a Fair Chance for Girls, said that neither girl nor woman can be educated while menstruating. She must lie down, rest, and focus on menstruating. Some women were angry about this at the time and they said so. But what about all the other girls and women who took it at face value and went to bed even if they felt fine? What about all the girls who didn’t pursue math or science because they were told those subjects were for boys? What about all the women who had an idea but willingly handed it over to a man because they didn’t believe they had the skills or the time or the ability to bring it to reality? (I’m not even talking about the times men stole women’s ideas here; I just mean the times when a woman truly did hand over her idea of her own free will because it never occurred to her that she could be the one to develop it.

Belief matters, and the prevalence of white male inventors says more about who believed they could follow this path than it does about who was smart or hardworking or deserving.

Sometimes, as I’m sure you know, white men feel attacked when this is pointed out to them, probably because they think I am saying they had it easy. I am most definitively not saying that. For every successful inventor mentioned on this series, there were thousands of other white men who tried and failed. The odds of winning were very, very slim for anyone.

All I am saying is that the odds are even slimmer when potential business associates assume you’re a secretary, when you can’t borrow money under your own name, and when you’ve been told all your life that your place is in the kitchen and not the workshop. Let’s just say that it’s not a surprise which of the inventions I covered that did have female inventors: the disposable diaper and a poison to kill husbands. For obvious reasons, there weren’t a lot of male competitors to edge women out of those fields.

One final point on this series: taking a look at my fictional Mary made me feel a little differently about the changes I have witnessed in my lifetime. Yes, they have been massive and hard to keep up with, but there are also a lot of aspects of life that have not changed.

- Housework is done using more or less the same tools that existed when I was born: my vacuum cleaner, mop, sink, stove, fridge, freezer, and washing machine would all be recognizable if I time-warped back to the year of my birth. I believe I was supposed to have a single humanoid robot that could handle all of that for me by now, and I don’t.

- Transportation is done using more or less the same tools that existed when I was born: cars, planes, subways, and trains. I believe I was supposed to have a flying car or a teleporter by now, and I don’t.

- Diet is maybe a little different. But that seems to me more a matter of trends than it does technological innovation. We liked meat, carbs, sugar, and processed junk then, and we just like them in different formats now.

- Whether medicine is significantly different depends on which medical conditions you happen to have. Some of them do have vastly better treatments now. But a lot of conditions were uncurable then and are still uncurable now. The public health improvements have not been as dramatic and widespread as they were when vaccines, clean water, and birth control were newly accessible to the masses.

The fields that do seem dramatically different are communication, education, and business. The changes there are huge. It hasn’t escaped my notice that my day job did not exist in the year I was born, and even if it had, I couldn’t have done it fully remote as I do now. This side hustle podcast here was not even a concept. The word podcast was coined in the year 2004.

Personally, I’m hoping that inventions continue over the next few decades and deliver me cures for the various ailments that afflict my family, a robot that can clean my bathroom, and a flying car. If any of you can invent can go out in your backyard workshop and work on that for me, I’ll be grateful.

Thank you all for listening! This wraps up the series on Inventions That Changed Women’s Lives. I have a big thank you this week to Pete, who signed up as a supporter on Patreon. If you’re in a position to be as fabulous as Pete, click here for ongoing support with benefitis to you or here for a one-time donation. Your Christmas gift from me will be the announcement on the results of the poll for the topic of the next series.