In approximately the year 2300 BCE,

Sargon, king of Akkad, overseer of Inanna, king of Kish, anointed of Anu, king of the land, governor of Enlil: he defeated the city of Uruk and tore down its walls, in the battle of Uruk he won, took Lugalzagesi king of Uruk in the course of the battle, and led him in a collar to the gate of Enlil.

Later,

Sargon, king of Agade, was victorious over Ur in battle, conquered the city and destroyed its wall. He conquered Eninmar, destroyed its walls, and conquered its district and Lagash as far as the sea. He washed his weapons in the sea. He was victorious over Umma in battle, [conquered the city, and destroyed its walls]. [To Sargon], lo[rd] of the land the god Enlil [gave no] ri[val]. The god Enlil gave to him [the Upper Sea and] the [Low]er (Sea). (Source)

That little sequence was not one, but two separate inscriptions made to commemorate the man who built what is sometimes called the world’s first empire. I have questions about that designation because I’m not clear on why Sargon’s realm in Mesopotamia counts as an empire but Narmer’s realm in Egypt 800 years earlier (see last week’s episode) somehow doesn’t somehow doesn’t count as an empire? But whatever.

(I’m uncomfortably aware in this series that naming somebody as first of anything is fraught with difficulties.)

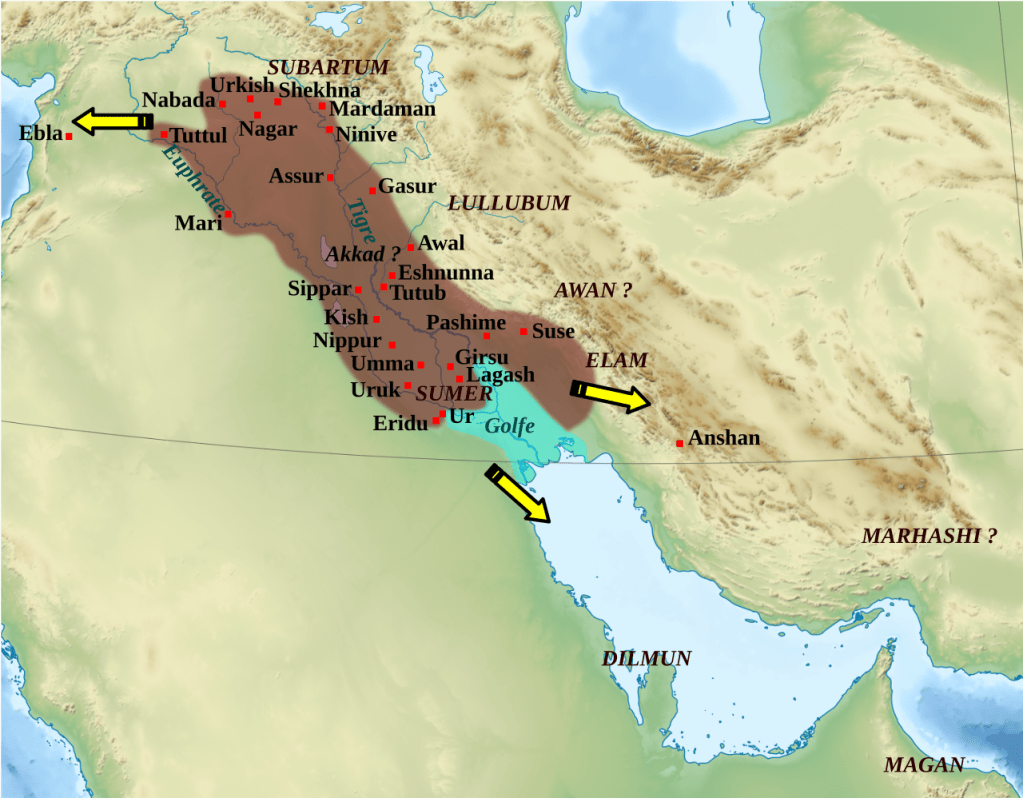

The land of Mesopotamia had been populated for a very long time before Sargon, but never as a single political unit. They were a collection of independent city-states until Sargon, king of Akkad, one of the northern city-states, conquered the southern city-states, collectively known as Sumeria.

Naturally, the Sumerians were not best pleased. Besides the very obvious reasons to be miffed, there was a question of language. Sargon spoke Akkadian, which is a Semitic language, related to modern day Hebrew and Arabic. The Sumerians spoke Sumerian, which is a language isolate, related to nothing in the modern world. Sargon’s new empire made Akkadian the official imperial language (Helle, 107).

High Priestess of Ur

Sargon was well aware that his new empire had political and cultural divisions. But religion was a point on which he hoped they could find some common ground. They all worshipped the god Enlil. Sargon probably did many things to calm the troubled waters, but the only one that concerns us today was that he appointed his daughter as high priestess in the Sumerian city of Ur.

We don’t know this daughter’s birth name. The name she would make famous was surely not her original name because it reads more like a title:

En—which means high priestess or ruler

hedu—which means ornament

ana—which means of heaven

Put it together and she is Enheduanna, high priestess, and ornament of heaven (Helle, 104, Halton, 5 1).

We know absolutely nothing about how Enheduanna felt about her assignment in a city that was not where she was from and which spoke a language which was not her own.

We do know that Ur was already an ancient and bustling city.

From the pictures, you have to wonder why anyone would build a city there. It has nothing but rocks and sand. Not a hint of any green anywhere. But that’s because the coastline has moved in the past 4300 years. Ur was a well-watered port city during Enheduanna’s time. Its harbor was full of ships bringing luxury goods from Egypt and India and maybe farther afield.

The holy temple in Ur was already centuries old and dedicated to Nanna, the moon god and patron god of the city of Ur. The office of high priestess was also centuries old, so Enheduanna was stepping into a well-established role as the human embodiment of Ningal, the goddess wife of Nanna (Helle, 1133-116).

This meant Enheduanna would never marry or bear children; she was symbolically married to a god. No word on how she felt about that, but there were compensating powers. She supervised the temple complex, officiated at rituals, and acted as a general diplomat on behalf of her father toward the local population (Halton, 51).

By inference, we can assume that she did all this very well. Exact dates are hard to pin down, but the indications are that she served in this role for at least twenty-five years and maybe more than fifty years (Helle, 106). She died while still holding the office (Halton, 51).

I don’t know the details of the rituals she presided over, but the shrine in her temple was honored with regular gifts of cheese, butter, dates, and oil (Halton, 51). Also, there was hymn singing, and that is the reason we are talking about Enheduanna in this series.

Exaltation of Inanna

Hymn singing doesn’t require writing. It was probably millennia old.

Writing was also nothing new. Sumerians had been doing that for about 1,000 years. But for most of that time writing was a skill for accountants. Seriously. Sumeria didn’t invent writing for the purpose of recording great insights or lofty ideals. Nope, they did it to record receipts and make sure the creditors got paid (Halton, 10).

But after 700 years of tallying the credits and the debits, it did occur to some that there are other uses for writing. The literati were branching out into other genres. There are hymns that predate Enheduanna, but all the early texts are anonymous. It doesn’t seem that it occurred to the earliest authors to sign their work, any more than people signed their pottery or their arrowheads or anything else that they made.

Until Enheduanna. She is not just the first female named author in history. She is the first named author period. Of any gender.

The most celebrated of her works is the Exaltation of Inanna.

Inanna is not the same deity as Nanna, to whom Enheduanna was a dedicated priestess. Inanna was a goddess that Enheduanna chose for her own personal devotion. Inanna was the goddess of war, love, fertility, and beauty. She was sometimes called the Queen of Heaven. Inanna was her name in Sumerian. In Akkadian, she was called Ishtar, and that is sometimes associated with Ashtoreth, a goddess mentioned in the Bible.

Enheduanna begins her Exaltation of Inanna like this:

“Queen of all powers,

downpour of daylight!

Good woman wrapped

in frightful light, loved by

heaven and earth”

…

“You are like

a flash flood that

gushes down the

mountains, you

are supreme in

heaven and earth:

You are Inana.”

…

My queen, hearing

Your battle cry the

Enemy bows down.

Fleeing sandstorms,

Terror, and splendor,

Humanity assembled

To stand before you

In silence, and of all

The gods’ powers, you

took the most terrible.”

(Helle, 7-8)

If this is all you know of the Sumerian pantheon, you would probably think Inana was the most powerful deity in the pantheon. She’s not. Enheduanna is elevating her. It even says as much in the poem. Enheduanna later says “You were born to be a second-rate ruler, but now! How far you surpass all the greatest gods” (Helle, 16).

Enheduanna also explains why she is elevating Inanna this way: she needs help.

Within the poem itself Enheduanna explains that she has served faithfully as high priestess of Nanna, the moon god. But a rebel named Lugal-Ane has driven her out of the temple and the city of Ur. Nanna is silent, and so Enheduanna appeals to Inanna to take precedence, have mercy, and restore Enheduanna to her position (Helle, 16).

Enheduanna begs Inanna to demonstrate her power:

“Let

them know that you

are as mighty as the

skies. Let them know

that you are as great

as the earth. Let them

know that you crush

every rebel. Let them

…

know that you grind

skulls to dust. Let

them know that you

eat corpses like a lion

(Helle, 16-17)

Yeah, it goes on a bit.

Anyway, Enheduanna says that she has given birth to this hymn by night, and now it will be repeated at midday, for Inanna has heard her and all is well (Helle, 18-19). So what we have is a composite composition: the first part done when Enheduanna was out of the city of Ur and needed help, and the final bit added to the end to say Thank You. You did it. I’m back.

The revolt of Lugal-Ane does appear to be a real revolt against Akkadian rule. Not against Sargon, who was dead by this point, but against Naram Sin, his grandson. For the details on how this rebellion affected his aunt, high priestess of Ur, we have only this poem to attest that she was driven out for a while. And then, by the grace of Inanna, she returned triumphant (Helle, 105).

Enheduann’s Other Attributed Works

The Exaltation is not the only hymn attributed to Enheduanna.

There is another Hymn to Inanna. Enheduanna elevates her to the supreme spot in the pantheon in that one too, but without giving such a personal and immediate reason for saying so. It starts:

“The large-hearted lady, the wild queen, joyous amongst the Anuna gods” (Halton, 80).

Besides those two hymns, there is also a tale, the story of Inanna and the mountain range of Ebih. Ebih did not show Inana enough respect when it refused to grovel at her feet. Inanna appears in full battle array, goddess against mountain range, and she wins, as of course we knew she would (Halton, 87).

There is also a song cycle of 42 Temple Hymns, each one much shorter than the three individual poems I have just discussed. These hymns were not to Inanna. The temple hymns are directed to different deities as worshipped in 36 cities, including northern and southern Mesopotamia, thus unifying Sargon’s empire through cultural and religious means (Halton,3). Hymn 8 is to Nanna, the moon god of Ur. Hymn 16 is to Inanna, the patron goddess of Uruk.

All of these poems, from the Exaltation to the Temple Hymns are written in Sumerian, which was probably not Enheduanna’s native language, but was the language of her adopted city, where she lived most of her life.

After her death, the empire went on for a while, but things changed. New rulers took over, power lines shifted. Akkadian took over as the language of the common people. Sumerian survived as the language of religion and scholarship, exactly the same way Latin filled that role in Europe for centuries after it ceased to be a living language.

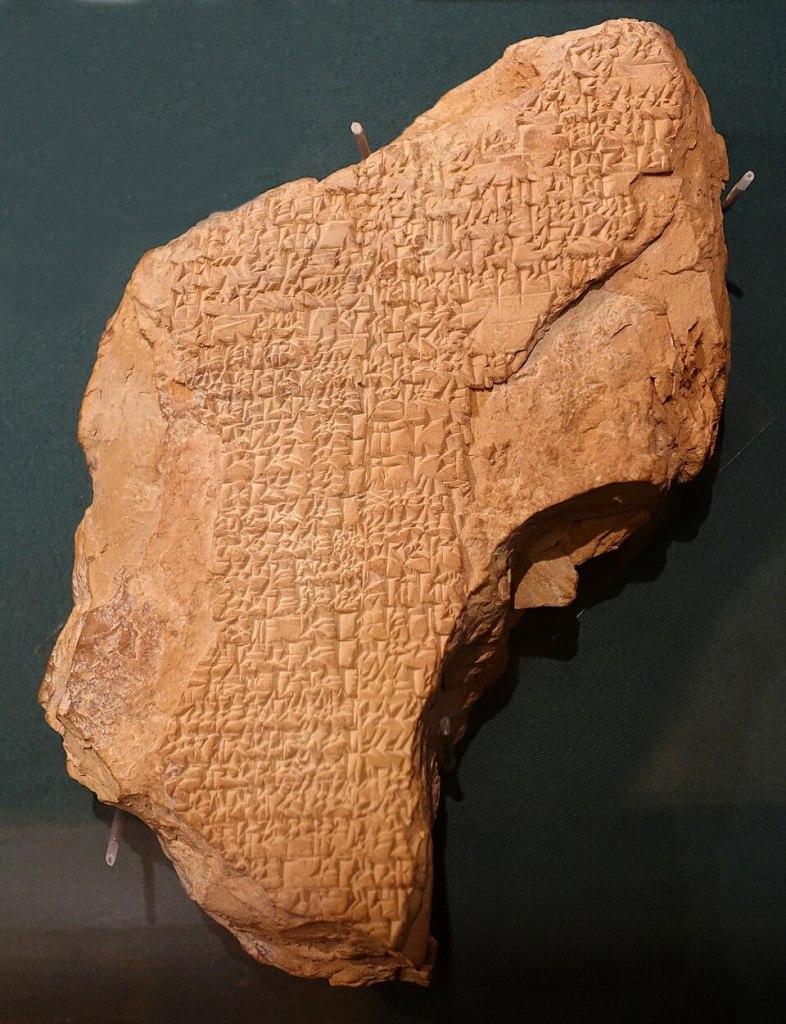

In the Old Babylonian period (this is hundreds of years after Enheduanna), students at school studied and copied her poems. The Exaltation of Inanna was copied so many times that it has been called the world’s first bestseller (Helle, 123).

Authorship Debates

All those copies are the reason why we can still read Enheduanna’s words today. Even when a copy is damaged, it’s hopefully damaged in a different spot than the next copy, so much of the text can still be pieced together. Even so, we’re still missing bits.

But all those copies also mean that some scholars doubt that Enheduanna actually wrote the hymns at all. Because we don’t have the clay tablet she wrote on. We only have the copies from hundreds of years later. So sure—the argument goes—but they were attributed to Enheduanna, but they were actually composed much later, so the argument goes.

To prove it, they point to one of the hymns in the Temple cycle, which clearly refers to a king who lived after Enheduanna’s time, and a few others where it’s less clear but certainly suspicious. There are also some technical linguistic things that sound like the language and wording of later times than Enheduanna’s.

Her defenders have a lot to say on the other side of the argument. That temple hymn with the clear reference to a later king is also clearly labeled as addition. So she didn’t write that one! Doesn’t mean she didn’t write the others. Or at least the last one in the set of 42, which is most clearly identified as hers.

There’s also some reasonable debate about what does authorship mean anyway? Is it the person who conceives the idea and the wording? Or the person who literally presses the cuneiform into the wet clay? Those don’t have to be the same person. Dictation is a thing. If dictation counts, then it would be possible for a person to compose the words and still be illiterate according to modern definitions because she spoke the words aloud and someone else wrote them down.

Alternatively, could authorship mean she was the rich priestess who commanded an underling to create a hymn, both conceptually and physically? In today’s world we would call the underling the author (or at least the ghostwriter), but authorship as a concept was new. Rich patrons certainly put their names on buildings and architectural works when what they meant was “I paid for this,” not “I am the artistic genius who designed this,” and certainly not “I physically built this with my own two hands.”

On an editorial note, if you’re making a new edition of someone else’s earlier work, are you allowed to update it a bit to make it more accessible to your modem audience? Are you allowed to riff on it, maybe add a few lines, maybe even add a whole hymn to a what is already a collection of hymns? How much do you have to change before it counts as your work instead of the original author’s work?

These are issues that intellectual property lawyers still argue in court, and Old Babylonian scribes didn’t have copyright law. Of course later scribes felt at liberty to make some “improvements”. They still attributed it to Enheduanna.

Why Doubt Enheduanna but Not Other Ancient Authors?

Everything I have just said is well and fully discussed in every one of the scholarly works. It’s unavoidable on this subject, and some people come down on the side of yes, she was the author. Other people say no, she wasn’t, but it’s still pretty cool that Old Babylonians even thought of attributing their work to a woman.

But I had a question that none of my sources discussed. My question was: Are we doubting whether Plato, and Aristotle, and Sophocles, and Euripides, and all the other Greek writers, really wrote the works attributed to them?

Because we don’t have the original papyrus or parchment or whatever it was that these people first set quill to. What we have is multiple copies made later by scribes who attributed the work to those particular Greeks. In many cases our oldest extant copy was written 1200 years after the original. There is no guarantee that the copyists were right or that they didn’t also make some “improvements” along the way.

I am not an expert on any of those men, but I studied them in school, and no one ever suggested they didn’t really write the stuff.

On the other hand, I have heard authorship debates about various books in the Bible. But that doesn’t really surprise me. The Bible is the foundational document for a religion that still has millions of practitioners. Loads of people have a vested interest in proving it genuine and loads of other people have a vested interest in proving it false. Authorship debates are inevitable.

I have also heard authorship debates about Homer, whose work is often considered to be where Western literature starts, even though he lived a millennium and a half after Enheduanna. If he lived at all, that is. There’s no physical evidence that he did. We know his name from later Greek writers who said he was the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey. There is scholarly discussion on whether they were right.

But the Bible, the Iliad, and the Odyssey don’t seem to me to be a parallel cases with Enheduanna. She has more in common with the later Greek authors like Plato, Aristotle, Sophocles, and Euripides. As far as I know, no one on earth is still practicing her religion, so that vested interest is gone. And we do have physical evidence that she existed. Archaeologists in Ur have turned up several disks inscribed with her name and title, and they date from her own time period. We have the grave goods of her personal hairdresser, of all the strange things, and the personal seal of her estate manager (Gadotti, 2). She definitely existed, and she definitely held the role of high priestess in Ur. That’s more than we’ve got on most of the famous Greek authors.

I don’t know whether authorship means Enheduanna was the patron, the artistic director, the scribe, or all three at once, but my personal feeling is that there’s no good reason to doubt that she was deeply involved in the creation of at least most of the works attributed to her.

I’ve even wondered if the real underlying reason we’re having this debate is because there is still one significant difference between Enheduanna and all the many ancient authors we aren’t questioning. The difference is: she was a woman.

I have a special thank you to Kirby, who signed up as a Patreon subscriber. Fabulous supporters like Kirby do keep this show up and running for everyone. If you are able to help as well, click here for a variety of ways to do it, some of them with benefits for you, like ad-free episodes and bonus episodes.

Selected Sources

Black, Jeremy (2002). “En-hedu-ana not the composer of the Temple Hymns” (PDF). Nouvelles Assyriologiques Brèves et Utilitaires. 1: 2–4. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

Gadotti, Alhena. Enheduana: Princess, Priestess, Poetess. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2025.

Halton, Charles, and Saana Svärd. Women’s Writing of Ancient Mesopotamia an Anthology of the Earliest Female Authors. Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Helle, Sophus. Enheduana. Yale University Press, 2023.

Sanders, Seth L. “MARGINS of WRITING, ORIGINS of CULTURES,” 2007. https://isac.uchicago.edu/sites/default/files/uploads/shared/docs/ois2_2007.pdf.