According to traditional Chinese histories, the first emperor was Yu the Great, who controlled the great floods, possibly with the help of a yellow dragon and a black turtle and divine battle axe. If Yu existed (and that’s a big if), he established the Xia dynasty somewhere in the neighborhood of 2000 BCE. That predates the emergence of writing in China. We know people lived in China at that time; there’s plenty of archaeological evidence of that. But there’s nothing that would tell us they called themselves the Xia and were led by a man named Yu, who built irrigation canals and dikes, with or without the help of a dragon, a turtle, and a divine battle axe.

The second dynasty in the traditional Chinese histories is the Shang dynasty and unlike their predecessors the Xia, we know for sure the Shang existed because they left us archaeological sites and contemporaneous writing. The Shang period stretched from 1600 BCE to 1046 BCE.

Unsurprisingly, there’s more evidence about the end of the Shang period than there is about the beginning. Their capital city (at least for the late Shang) was near modern-day Anyang, China. If that doesn’t mean much to you, rest assured, you are not alone. We’re talking northern China. Not so far north as Beijing, but still pretty far north, roughly the same latitude as Seoul, Korea. The archaeological digs at Anyang have provided the oldest versions of Chinese writing.

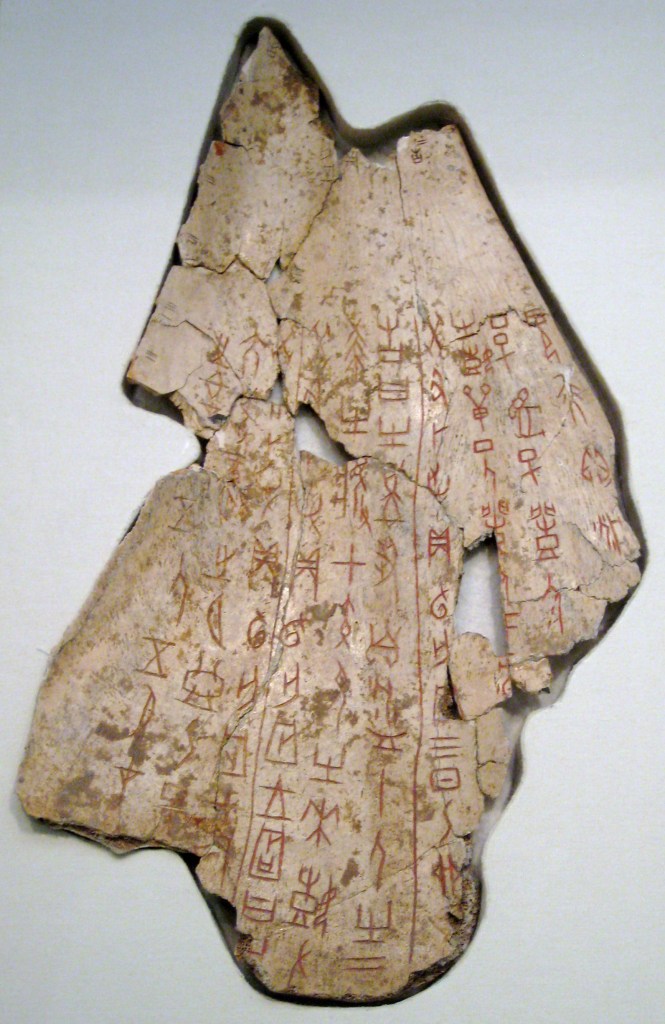

If you remember last week’s episode on Enheduanna (16.2), you’ll know that the Mesopotamians invented writing to keep track of their business accounts. The earliest Chinese writing was used for a different purpose: divination.

If you were a high-status member of the Shang and you wanted a glimpse into an uncertain future, you took a tortoise shell or an ox bone, heated it until it cracked, and then read your fortune in the cracks. Often, you then made an inscription on that shell bone, using early Chinese characters, some of which are still recognizable as Chinese characters nearly 4,000 years later. They’re recognizable even to me, based on my two years of college Chinese, which is practically nothing for a language so different than my own. That’s the beauty of a script that makes the symbols match the meaning, rather than the sound. It makes no difference at all whether we pronounce the words the same way. We can still sort of understand the writing. At least better than we would if the script were phonetic.

A complete oracle bone inscription included the date, the name of the diviner, the topic of questioning, the interpretation of the cracks, and a report on the results after the fact. Sadly for us, not every diviner actually answered all those questions (Wang, 2). Some of them took the easy route and inscribed less.

Happily for my podcast, it wasn’t just men who consulted oracle bones. There are many women mentioned, Lady Fù Hăo is just one of them, but we have over 300 bones about her. In many cases, the scribe only wrote her name. Which is not particularly exciting, but more than we’ve got for most women of this time period.

The Birth of a Girl

Thirty-five of Fù Hăo’s divinations were on exactly the subject so many women across history have had reason to get anxious about: childbirth.

Fù Hăo was one of many wives of king Wu Ding. The birth of her children was a matter of national concern, even though she wasn’t the first wife. I don’t know the intricacies of Shang policies, and I don’t think anyone else does either, but later Chinese emperors had many wives, and all of their children were considered legitimate heirs to the throne. There was no Henry VIII nonsense for them. Rather than eliminating one wife after another for failure to produce a son, the more likely scenario was fratricide because you had so many sons, and all of them hoped for the top job.

There were probably multiple reasons, both personal and political, why Fù Hăo wanted to know how her childbirth was going to go, and she consulted the oracle bones more than once about more than one pregnancy. In one case, we have the full complete results:

On the 21ˢᵗ day making cracks, Que divined, “Fù Hăo will give birth; it will be lucky. The king read the crack and said: If it was on a Ding day that Fu Hao gave birth, it would be lucky; if it was on a Geng day, it would be extensively auspicious.

“On the 31ˢᵗ day, Fù Hăo gave birth. It was not lucky; it was a girl” (Kwok 145).

Ho hum. Here we are at the dawn of one of the world’s great empires, and we have already decided the birth of a girl is a big disappointment.

Incidentally, the character for “girl” is one of those that is still more or less recognizable in the modern day. It has become more stylized, but originally it was a pictograph of a person kneeling. The argument has been made that this just proves that women were already subordinate. The counterargument is a little mindblowing, but true: the chair had not yet been invented in China. Sometimes it’s hard to remember that stuff like chairs needed inventing, but they did. In a world before chairs, kneeling wasn’t necessarily a sign of submission and low status. It was literally how you sat down, for both men and women. In many Asian cultures, it still is a common way to sit. So perhaps the pictograph isn’t really of a woman kneeling (in the Western sense of that word) but of a woman sitting, which is fine (Wang, 2). I’d be more than willing to go with that except for one thing: we already know women were subordinate from other sources. Such as the fact that the birth of a girl was called “unlucky”.

This is all the more irritating because Fù Hăo was clearly demonstrating to King Wu Ding what girls are good for, and I don’t mean making more babies. I mean leading the army. Why not?

Leader of Armies

Among the hundreds of oracle bones with Fù Hăo’s name on them, there are about twenty which clearly refer to her directing troops.

For example:

On the 8ᵗʰ day of crack-making, “Zheng divined: Fù Hăo will perhaps follow Zhijia to attack the Bafang. The king (on the other hand) will from the east attack Houxing before Fù Hăo takes up her position” (Kwok, 147).

Following here refers to military formations. It does not mean that Fù Hăo was subordinate to Zhijia, merely that her troops were coming up to support his. In many military maneuvers, that would actually mean Fù Hăo was directing the attack. Putting your top commander on the front line is a risky endeavor. Often you keep them at the back.

This is not a one-off inscription. Another bone says:

On the 18ᵗʰ day of crack-making, divined: “Raise Fù Hăo’s troops 3,000; raise lü troops 10,000; call upon them to attack the Jiang” (Kwok, 149).

The meaning of lü is unclear, but it’s not a name. It probably refers to a type of unit or soldier. This suggests that Fù Hăo led 13,000 troops, a very large number for the time period. William the Conqueror took England with an army that was probably smaller than that. George Washington crossed the Delaware with an army that was definitely smaller than that.

What the oracle bones don’t tell us are any of the details. It’s maddening. Inquiring minds want to know so many things, like why was Fù Hăo in command? Were these her troops which she maybe inherited and brought to the marriage? Did she win command by her personal prowess with a blade? Did she wear armor? Did she charge around on a white horse? Did she drive a chariot? (Chariots were new at the time; yes, some historical peoples had chariots before they had chairs.) Did Fù Hăo win? Did her subordinates mansplain warfare to her? Was she a figurehead? If she was a figurehead, why was she involved at all?

We just don’t know the answers to these questions.

We also don’t know if Fù Hăo was unique as a female military leader, or if she was one of many. Were any of her soldiers female?

It’s entirely possible that Fù Hăo was not the first female military leader, but she is the first one who left us written evidence of her role.

The oracle bones tell us a few other things about Fù Hăo as well. She was sometimes ill, no surprise there. She sometimes had nightmares, no surprise again. These things were sometimes caused by ancestor spirits, according to the divinations (Kwok, 151).

Those ancestor spirits could be good or bad. And sometimes it required a sacrifice to appease them.

On the 16ᵗʰ day of crack-making, “Que divined: Exorcise Fù Hăo from the spirit of Father Yi; cut sheep, offer pig, and stab ten penned sheep.” (Kwok, 151)

You may have feelings about the effectiveness of that remedy, but it gets more intense.

On the 14th day of crack-making, “Xuan divined, Exorcise Fù Hăo from the spirit of Father Yi; stab war-captives” (Kwok, 152).

Fu Hao’s Tomb

For many decades these oracle bones constituted the entire record of Fù Hăo’s existence. But in 1976, there was a major discovery, the kind every archaeologist dreams of.

Outside of Anyang, they found Fù Hăo’s tomb. And it was intact, by which I mean it had not been looted back in antiquity, like the vast majority of rich burials were.

In Egypt, Pharaoh Tutankhamen’s tomb astonished the world not because he was a particularly important or wealthy pharaoh (he wasn’t), but because his pretty-average-for-a-pharaoh grave goods were still there to astonish us. And they are astonishing.

Fù Hăo’s place in Chinese archaeology is similar. The size of her tomb is medium for a Shang-era tomb. Men got bigger tombs. Fu Jing, who was Wu Ding’s first and most important wife, also got a bigger tomb.

But Fù Hăo’s tomb gets all our attention because it was still literally stuffed with grave goods.

There were 195 bronze vessels, 271 weapons and tools, 755 jades, 110 objects of marble and turquoise, 564 objects of carved bone, 3 ivory cups, and 11 pieces of pottery (Cambridge, 194-195). Not to mention over 6,000 cowrie shells, which were probably the local unit of currency in Fu Hao’s time (British Museum).

All this in a medium-sized tomb. Wu Ding almost certainly got buried with more. Same with Lady Jing but will never know how full theirs were because their tombs were looted long ago.

A great many of Fù Hăo’s grave goods are inscribed with her name. That’s how we know it’s her tomb. And these grave goods might offer a clue as to whether she rode a horse or drove a chariot. There is a little horse gear among the tools. Not much, but a little, which suggests that maybe she did use horses, but they might not have been a large part of her life. This is compared with 89 dagger blades, many of which may have originally been mounted on wooden shafts (Loewe, 197).

Unfortunately, the bottom of her tomb was waterlogged, including the part with her coffin. Fu Hao herself does not remain, so we can’t answer questions like what did she die of? How old was she? How tall was she? Did she have any battle wounds?

Once again, we have no idea.

What we do know is that she didn’t go into the grave alone. At least sixteen people were buried with her and also at least one dog. It has been suggested that the two very large axe blades inscribed with her name were used to behead the sacrificial victims chosen to go to the grave with her (Loewe, 197).

Fù Hăo’s tomb was sealed up in about 1200 BCE. It’s not in the main royal cemetery, which is another indicator that her status was not as high as Fu Jing’s, the first wife. But it’s also probably why grave robbers didn’t find it. It’s very close to a river, and there’s a possibility the entrance was covered by silt early enough that no one could get access while they still remembered it was there.

She lay undisturbed and forgotten through many wars, including ones led by women like Boudicca (ep. 12.3), Zenobia (ep. 12.4), Lakshmi Bai (ep. 12.12), and Joan of Arc (who I have not yet covered). None of these women knew about Fù Hăo, but they were still following in her tradition.

This week I have a special thank you to Linda, who signed up as a supporter on Patreon. Spectacular people like Linda help keep the show up and running for everyone. If you’re able to contribute as well, please click here for a variety of ways to do it.

Selected Sources

British Museum. “The Tomb of Lady Fu Hao.” Archive.org, 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160327180140/http://www.ancientchina.co.uk/staff/resources/background/bg7/bg7pdf.pdf.

Kwok, K.-C. (1984). The tomb of Fu hao (T). University of British Columbia. Retrieved from https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/ubctheses/831/items/1.0096363

Loewe, Michael, and Edward L. Shaughnessy. The Cambridge History of Ancient China : From the Origins of Civilization to 221 B.C. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Nelson, Sarah M, and Myriam Rosen-Ayalon. In Pursuit of Gender : Worldwide Archaeological Approaches. Walnut Creek, Ca: Altamira Press, 2002.

Wang, Robin. Images of Women in Chinese Thought and Culture: Writings from the Pre-Qin Period Through the Song Dynasty. United States: Hackett Publishing Company, 2003.