In the past five episodes, we have discussed five different women who didn’t know about the glass ceiling, took matters into their own hands, and seized control of their respective empires (Cleopatra, Wu Zetian, Elizabeth I of Russia, Catherine the Great, and Ranavalona). Were there other women who did this? Definitely. History is vast, my attention span is short. So after today we will be moving on to other topics.

But before we leave the topic, I thought it would be good to sort of correlate lessons learned from each of these five women, just in case you have plans to make any power grabs yourself. Along the way I will tell you a couple of other women who I wanted to include in the series, but couldn’t for one reason or other. So here it is an absolutely foolproof plan for political domination, three steps only, and available free of charge, though I hope I get some kind of compensation when you become a supreme dictator. At any rate, here’s the plan:

Step 1: Get yourself into the royal family.

So one common theme you see among these women is that they are not just some random girl off the street. As much as we would like to believe life is a meritocracy and talent rises to the top and all that, it is a questionable premise now and just absolutely not true in most of human history. So we have Cleopatra who is indeed the crown princess, though I think I just made up that term. We have Elizabeth of Russia who is also the daughter of a king. That helps, in both cases. If you’ve fluffed that already, you still need to be highborn enough to marry into the royal family, which is what, Wu Zetian, and Ranavalona did. Without that, we’d never have heard of any of them. Of my five women, Wu Zetian may have been the lowest born, being the daughter of a mere lumber merchant, but note that she wasn’t the daughter of, say, a day laborer in the rice paddies.

Now in history, as soon as you state a rule there’s an exception, and this is no exception. Because there is a case of woman seizing power who was neither royal, nor highborn, nor even humble lumber trader. Her name was Musa, and she was a slave girl, the lowest of the very low. I would have loved to have had an entire episode on her in this series except for one problem. We know almost nothing about her, certainly not enough to fill a whole episode. So you’re going to get her story right here.

The Jewish historian Josephus gives us the chronicle of Queen Musa of Parthia. Parthia, in case you are scratching your head, is not on any modern map. The Parthian Empire was based in Iran, though like all empires, its borders shift over time. It was on the eastern flank of the early Roman Empire. Rome had big plans to grind its foot into Parthia, and they periodically send over an army intent on doing just that, but it usually didn’t go that well. In between all the invasions, Rome occasionally decided to try getting along, just for a change. In 20 BC or thereabouts, the emperor Roman Augustus (he who crushed Cleopatra and commanded all the world to be taxed) gave a gift to Phraates IV, king of Parthia. And the gift was: an Italian slave girl named Musa.

As you might expect, Musa was just a concubine in the royal harem. Until she gave birth to a boy. Like many polygamous societies, all boys born in the harem were potential inheritors of the throne, so this is a big boost in status for mom. Indeed, Phraates elevated her to the rank of Queen, though since he had more than one queen, this isn’t as big a jump as you might expect. But still—no longer a concubine.

Having gotten this far, says Josephus, Musa just has to get rid of all the older princes to make sure that it’s her son who inherits. She accomplishes this by convincing Phraates that when Rome demands royal hostages to ensure Parthian good behavior, it’s these older princes who must go. So off they go, which means that her son is now the crown prince and Musa becomes the Main Queen as the mother of the heir. Most slave girls would consider that victory enough, but not Musa, because she and her son then poison Phraates. He dies. Her son Phraataces assumes the throne, but of course he’s weak and young, needs a guiding hand, so Musa marries her own son, thus becoming both the Queen Mother and the reigning Queen Consort, which in this culture means she is reigning jointly and is in fact deified. Pretty good for a former slave girl. Now you might remember that Cleopatra, while not marrying her son, did marry her brothers, so this whole marrying your close relations is not unheard of in this climate. But mother and son is stretching it pretty far, and Josephus insists that this was no mere marriage in name only. Nope, this was the real deal, physical relations and all. Also, they continued to irritate Rome, though I’m pretty sure the feeling was mutual. According to Josephus, it was the nobles’ shock and horror at the incest eventually led them to rise up against her and that was the end of her meteoric career.

And that’s it. The whole deal. There is no other information. Not even when, where, and how she died. The part we do know is entirely from Josephus, Parthian sources being a very rare thing. What’s interesting here is that the Roman and Greek sources are absolutely silent on the existence of Musa, which is odd, because they definitely record the presence of the Parthian hostages in Rome. Indeed, we might think that Josephus just imagined the whole queen thing except that we have coins that show Phraataces on one side and Musa as his co-ruler on the other. We also have a Hellenistic bust of a queen of Parthia, which has been identified as Musa, though I do always wonder how art historians tell one marble bust from another. They all look pretty much the same to me. Other historians reject that identification, but the coins are definitely the real deal, and I’ve put a picture on the website. So there was a woman named Musa. Whether Josephus got all the details of her life right … well … [sigh] … the life of a historian is hard. One paper I read on the subject says that Augustus was silent about Musa deliberately, out of spite because she was clearly more interested in the glory of herself rather than the glory of Rome. I personally think that if you give a girl away to a foreign court hundreds of miles away you shouldn’t be all that surprised if she’s not overflowing with gratitude and loyalty, but maybe that’s just me.

Musa of Parthia, who may (or may not) have had the most extraordinary rise of power of all the women in this series, having started as a foreign slave and ending up queen regnant.

Image By Classical Numismatic Group, Inc.

So after that lengthy digression, let’s return to the main point, which is that by and large, if you want to seize power it’s best to be high born, preferably royal. And if you’ve missed that boat, you need to marry in.

Step 2: Make sure your rivals are weak.

The fact is that if your brother or husband or whatever is strong, you aren’t going to win. It’s just a fact. In the field of power plays, being female is a serious weakness.

But fortunately for you and your dreams of world domination, femininity isn’t the only weakness. Extreme youth is a weakness. Cleopatra had brothers, but they were much younger than she was. The story would have been very different if she had been the younger sibling.

Bad health works as a weakness too. Wu Zetian had a sickly husband and a son with a speech impediment.

Seriously bad PR works too. Catherine the Great had a universally despised husband, who was known to be openly antagonistic toward his own people, but I would add that this would never have worked for most women. Hated kings are a dime a dozen, but it’s not often that the queen steps in and deposes him. Catherine was amazing.

The problem with all of these weaknesses is that they are just as likely to apply to you as to your rivals. So for example, let’s take Jeanne II of Navarre. Jeanne was born when her father Louis the Headstrong was the crown prince of France, which is a pretty good start in life. Unfortunately, in 1314, her mother Marguerite was arrested for adultery and sent to prison, raising all kinds of speculation about whether Jeanne herself was really the daughter of the crown prince. Or was she merely the daughter of a household knight? Who could tell? It is at this point that I am reminded of a line from that excellent movie Tea with Mussolini, which says “There are no illegitimate children, only illegitimate parents.” But the medieval mind did not work that way.

Since she was nothing but a girl, you might think that all of this would perhaps not matter much in France’s history (though to be sure it mattered to the two-year-old Jeanne). However, Louis the Headstrong was now in a veritable pickle. He had one child, she was a girl, his wife was still alive, but locked up in a castle, so there would be no more children there, even if he had still wanted her, which is to say the line would end with him, which was all the more urgent when his father died and he became Louix Xth. He needed a crown prince and for that he needed a wife, and an unfaithful jailbird was not going to get the job done.

Now the official story is that Marguerite caught cold and died, probably weakened by bad treatment in prison. The unofficial story is that Louis ordered her strangled, which thus served both as his vengeance and also a clear path to his second marriage to Clementia of Hungary. Clementia did become pregnant rather quickly, (what joy!), but Louis himself died of either pneumonia or pleurisy or poisoning, take your pick.

And now France was the one in a pickle. Because if Clementia bore a boy, then he was rightborn king of all France. But if she bore a girl, or lost the baby (which was not uncommon), then the only heir was little Jeanne, and she was weak in the extreme, being a girl (strike 1), being young (strike 2), and being strongly suspected of being illegitimate (strike 3 and out).

As it happens, Clementia did bear a boy (what joy!), who bears the unfortunate moniker of John the Posthumous, as he was born after his father’s death. He holds the very great honor being the only French monarch to be born into the title and also the only one to hold it for his entire life, which I am sorry to tell you was only five days. He also holds the record for shortest reigning monarch in French history.

But the point of all this is that Jeanne was then the only heir, right? So she inherited and became queen regnant, right? Nope. Her uncle Philip assumed the throne. His justification was Salic law, which supposedly was the law laid down by the first Frankish kings 800 years earlier which cut women out of property inheritance. Philip’s insistence that it should also apply to the throne of France would become set in stone which is why you have never heard of a Queen Regnant of France. They were specifically and eternally excluded on general, legalized principle. It is interesting to speculate what would have happened if Jeanne had been older and feisty. Mary, daughter of Henry VIIth of England, was also a girl and was also accused of being illegitimate. She still managed to become queen. But I doubt that Jeanne could have made it work that way. Mary’s greatest rival was her half-sister Elizabeth, also a girl. Jeanne’s rival was her uncle, and he was strong.

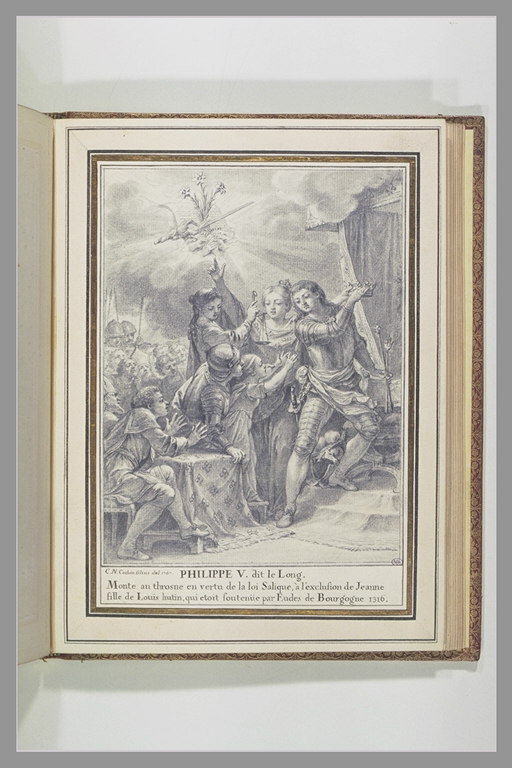

This 18th century engraving shows Philip the Long ascending to throne of France over the pleas of the four-year-old Jeanne, who would otherwise have inherited the throne from her father Louis X. Being young, female, and possibly illegitimate, Jeanne just had too many strikes against her to succeed in a power play.

The point is, you have to be strong. And being a girl is such an inherent weakness, that your rivals must be even weaker if you’re going to have any hope of success. In Jeanne’s case, she did become Queen Regnant of Navarre, but only because she inherited that from her mother’s side, which was never in any doubt. It is possible that Jeanne felt just a little vindictive satisfaction, when Philip also did not manage to produce a son and power moved away from his line because his own law had eliminated his daughter as a candidate.

Step 3: Get rid of any moral scruples, assuming you had any to begin with.

Not one of my five power-grabbing women was the kind of person I’d call kind, considerate, and caring. Not one of them followed the golden rule, turned the other cheek, or said “hey, let’s just let bygones be bygones, and start fresh, huh?” All of them committed at least some atrocities, usually against their own close family members. In fact, the list of murders, torture, incest, backstabbing, and general shabby behavior has gotten a little oppressive, and a fair amount of it has been against close family relatives. I mean, your family may not be perfect, but I imagine that you’ve never poisoned a brother, mutilated an in-law, condemned a cousin to solitary confinement, ordered someone to strangle your husband, or executed your extended family on general principle. If you have done any of these things, I don’t want to know about it, but it will stand you in good stead in your power grab because seizing power is not for the squeamish or mild-mannered.

Here’s the hard truth: power pretty much always comes at the expense of someone else. In modern democracies, that means the losing candidate in the election gets humiliated. In a monarchy, that very often means the loser dies, often in a gruesomely inventive way. And that’s just the real political opponents. I haven’t even gotten started on what happens to the general population. Some of these women committed out and out crimes against humanity with the general population, and even those who weren’t especially bad according to the standards of their own day weren’t exactly out there preaching tolerance and equity and presents for everyone. Catherine comes the closest, and her talk was better than her actual action.

These women were widely criticized for their behavior, and I’m not trying to excuse it, but I will point out that the great Kings and Emperors of the past were not significantly different. And you can really see why you look at the later Roman Empire. You get all kinds of political intrigues, assassinations and the like and when you realize that some of these emperors literally last days, just days, before they get bumped off, you start to wonder who in their right mind would want to be emperor? Far better to just retire to your country villa, eat some olives, grow some grapes, oppress some serfs, chase the local women with or without their consent, maybe write poetry, or start a podcast. You know, the simple life. You’ll live longer.

But there’s a reason why otherwise intelligent people fight over the top job, fraught with danger as it is. One reason is the obvious of appeal of power and money. The other reason is fear. Because even if you think the retire-to-a-Tuscan-villa plan sounds nice, if you have even a smidgeon of a claim to the throne, then all the other people with a different smidgeon of a claim will view you as a threat. And you will be eliminated, one way or another. This is most obvious with Elizabeth of Russia, who made her play because she was told her alternative was life in prison. But to a great extent it’s true of the others too. Catherine’s husband was preparing to get rid of her. Ranavalona’s rival would have killed her on general principle. Wu Zetian, by custom, should have spent her remaining life in a monastery after the death of her first husband. Cleopatra had every reason to expect that if her younger brother had defeated her, he would have poisoned her, just as she probably later poisoned the even younger brother.

The world of power was one of kill or be killed, imprison or be imprisoned. Anyone who had too many moral scruples got snuffed out. And that makes some of the behavior maybe just a little more understandable. The one I feel most sorry for is Elizabeth. You really get the sense that she would have been happier being the princess all her life. She could have married openly, held lots of parties, and generally enjoyed life. But no. Fear, brutality, and constant backstabbing seems to be the common lot of those who are too close to power, whether they want it or not. And you can’t relax after you stage your coup because nothing will change as you get older. Every one of these women faced challenges to their power throughout their lives. Constant vigilance will be your lot in life. I myself will be doing the Tuscan villa thing, just as soon as I can afford it.

Three other small points before I close out this series:

- Of my five women who seized power, not one of these women lived in a culture that followed strict patriarchal primogeniture. Cleopatra was significantly helped by the fact that Ptolemaic Egypt had a male-female co-ruler thing going on. If she had lived in a strongly patriarchal society, she probably wouldn’t have won. The polygamy thing sort of helped Wu in a way because her sons were just as legitimate as any other wife’s sons. In Russia the nobles were supposed to choose the next monarch, and in Madagascar, power was supposed to go to the king’s sister’s son. Just a commonality here which is interesting primarily because it’s in the strict primogeniture cultures that women are more likely to come to power in more legitimate ways: that’s why England has so many great queens, not one of which is featured here. They inherited, more or less.

- Next point, as much as some would like to believe that if women ruled the world, everything would be peace, harmony, and women’s rights, the evidence does not bear that out. These women waged war, both offensively and defensively. They also weren’t raging feminists. They didn’t attempt to change the inheritance laws. They didn’t upset the social order. Wu Zetian probably did the most along these lines, but it didn’t stop China from being a strongly patriarchal society.

- I really wanted to have more female queens and chieftains from less prominent countries. Like a Native American chief would have been really great, and there are documented women rulers of Native American cultures. Unfortunately, they usually aren’t well documented. None of the ones I looked into had enough readily accessible info for me to determine how they came to power. Did they seize it? Or was it just business as usual in their culture? More research will be coming your way at some future date to answer these questions.

Selected Sources

Gregoratti, Leonardo. “Parthian Women in Flavius Josephus” in Martina Hirschberger (ed.), Jüdisch-hellenistische Literatur in ihrem interkulturellen Kontext”, Düesseldorf, 10.–11. Februar 2011, Peter Lang Verlag, 2012, pp. 183-192

Hallam, Elizabeth M, and Charles West. Capetian France : 987-1328. London ; New York Routledge, Taylor Et Francis Group, 2020.

Strugnell, Emma. “Thea Musa, Roman Queen of Parthia.” Iranica Antiqua, vol. 43, no. 0, 31 Jan. 2008, pp. 275–298, https://doi.org/10.2143/ia.43.0.2024051. Accessed 20 Sept. 2019.

Love your photos!

LikeLike