I admit that this episode isn’t strictly about women, but the early history of money is not what most people expect and it makes a nice backdrop for future episodes which are about women, so here we go.

The Barter System (or not)

Aristotle was one of the first writers to ponder the origin of money, and though he was born 2,400 years ago that was long after the invention of money. In his book Politics, Aristotle wrote that people had originally traded goods by the barter system, but that it was simply too unwieldy for complicated trades and so people agreed to use money, a thing which was more easily dividable and countable than the actual goods (Orrell, 11).

This makes a great deal of sense. If, for example, I’ve got some apples and you’ve got some chickens, then we have to figure out how many of my apples I should give you for a chicken, which will be difficult enough. But then what if you don’t want apples? You actually want wool, which I don’t have, but a third party does have wool and does want apples, and now we’ve got a third person in the mix and we have to please all of us, which will be difficult again because while I am the soul of honesty and fairmindedness, the same can’t be said of everyone, and on top of that maybe you want white wool not black so we need a fourth person with a different kind of wool to make this work and that person wants my apples but not for another month or so when she has time to make cider. It’s complicated, so people cast around for an easier method and money naturally evolved as a better system for accomplishing the same thing. I sell my apples for money. I buy your chicken with money. I hesitate to say that everyone’s happy because we know money doesn’t buy happiness, but it works and it’s an improvement over barter so that’s how the world as Aristotle knew it got to where it was.

This theory is so logical that it has been repeated by medieval university professors, and Adam Smith, and countless modern textbook writers. It has only one major flaw and that is that there is no evidence whatsoever for it.

We’ve never actually seen a true barter economy in the wild (Orrell, 15). That’s not to say that no barter happens. It certainly does. But in the moneyless societies studied by anthropologists, barter is rare. What generally happens when I’ve got apples and you don’t is that I just share them with you. Free of charge. No chickens. No money involved. Why would I do this? Well, because I am not making a transaction. I am building a relationship. So I share my apples with you, partly because I am a super nice person but also because it builds trust. And I trust that at some future point when you have chicken, you will share it with me. But it’s not about whether the amount of apples is worth the amount of chicken. We’re just sharing what we have when we have it. So there’s no problem with all those complex calculations because we aren’t making any.

Barter is what we do with enemies. When there is no trust. If I don’t trust you to share with me in the future, then you better believe I want my payment now, thank you very much. Nebulous promises mean nothing.

All this is interesting when you compare it with the modern world because it suggests that nowadays pretty much everyone is an enemy. Immediate families may (or may not) trust each other enough to make finances work like that, but it’s for sure that my local grocery store does not view me in that light. Nor, for that matter, do I feel that way about my local grocery store.

So that’s the problem with Aristotle’s theory. Moneyless societies didn’t need to invent money because they weren’t making many transactions in the modern sense.

Transactions

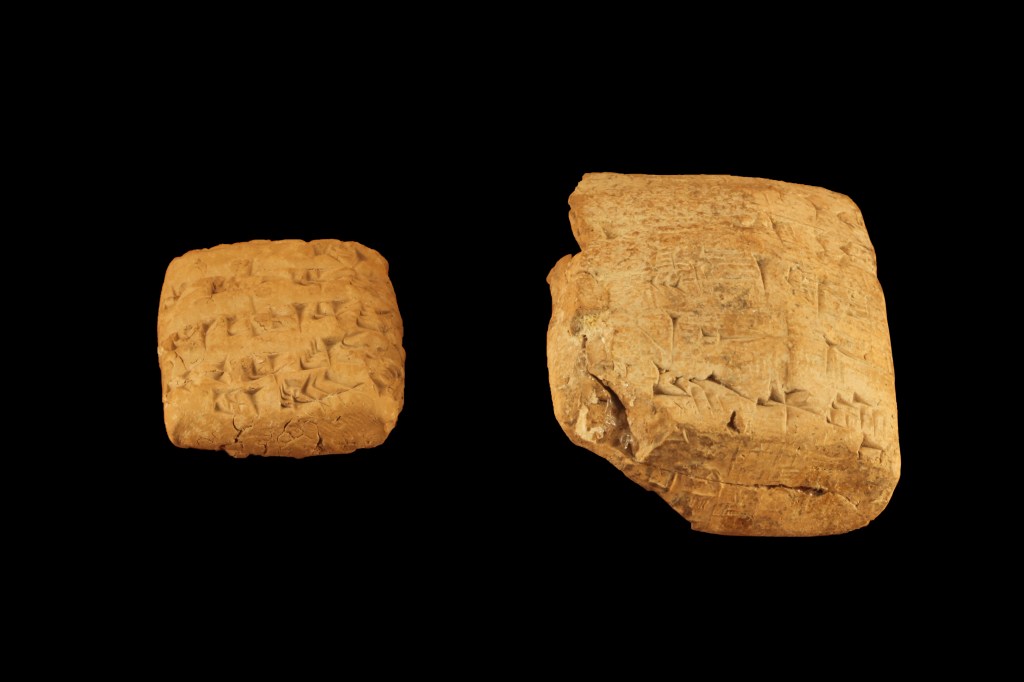

Transactions are right at the heart of civilization. I would like to believe that humanity invented writing because of a great drive to express their deep thoughts about life, the universe, and everything. But sadly, the earliest texts turn out not to be written by poets or philosophers, but by accountants. The ancient Sumerians kept their records in cuneiforms. The city of Ur in modern-day Iraq had a famous ziggurat or temple where the priests used reeds to inscribe transactions onto the clay tablets. Like the time system that we still use today, their money system was built on multiples of 60. So a shekel is about 8.3 grams. A mina is 60 shekels, and 60 minas was a talent (Orrell, 15-17). Note that we’re not talking about coins here because they haven’t been invented yet. This is just a unit of weight like a pound or a gram.

A cuneiform tablet with an envelope that is now broken. The Sumerians recorded debts on clay envelopes and marked with a seal, which would be broken when the debt was paid. This particular one promises to pay 48 workers for 11 days to haul a boat full of flour north to the town of Nippur. The envelope is witnessed by Mansina, son of Lukirzal.

This object is in the Louvre. The image is by Rama, found on Wikimedia.

The Laws of Eshnunna give us a sense of prices. For example, one shekel in silver was worth 12 silas of oil. A sila was about a liter. Or your shekel of silver could get you 15 silas of lard, 300 silas of potash, 600 silas of salt, or 600 silas of barley. And that’s just the food items. A Sumerian-about-town with a shekel of silver could also get herself 180 shekels of copper or 360 shekels of wool. Legal penalties were also fixed in shekels of silver. So if you bit off someone’s nose, you’d be fined 60 shekels of silver (or 1 mina). I really don’t want to know how many times that particular penalty was exacted. Biting off a finger was only a 40-shekel fine, and a slap in the face was only 10 shekels (Orrell, 17).

You might be imagining Sumerians walking around with wallets full of silver, so let’s clear that up. They weren’t. The silver didn’t actually circulate. It was just an accounting device. The silver was kept in a vault, and if you had to pay the state for something, then a priest would write it all down in cuneiform, sort of like debiting your bank account. The money goes in and out, but you never actually handle it. You just watch the numbers go up and down on your balance. If you owed something to someone outside the palace, you probably paid in goods, but the prices might still be reckoned in silver shekels as a handy basis for setting the prices. Larger debts might be recorded on clay envelopes and marked with a seal, which would be broken when the debt was paid (Orrell, 18).

In many cases the promise on the clay envelope was to pay the bearer, not the creditor, which meant that your creditor could sell the envelope. In that sense, these envelopes were very much like paper money today. They are of negligible value in themselves, but we use them on the understanding that they are tradeable for things that are of value (Orrell, 18).

If you’re wondering about interest, yep, the Mesopotamians thought of that little idea too, one theory being that it was based on the idea that a herd of livestock will get bigger while someone else is borrowing it, and hence more valuable. Rates could be as high as 20%, and by Hammurabi’s time it might even be compound interest, rather than simple (Ferguson, 30).

And yes, since you’re asking, women were included in these financial transactions. Women ran businesses, employed others, enslaved others, and served as priests. Of course, they were also sold as slaves.

Debts and Debtors

What all this means is that money did not evolve to make barter easier. What evolved in Mesopotamia was debt. People (and the state) are still offering their services and goods for no exchange at the time, only now they want assurance that you will also share when your harvest comes in and that you will share in sufficient amounts to compensate them for what they’ve laid out for you. Trust is gone, my friends. Trust is gone. We still have a relationship, yes, but it’s no longer one where we link arms and sing “We Are Family.” Nope, now our relationship is that of creditor and debtor, generally between the state as creditor and the masses as debtors. And money is handy way of greasing these transactions. We don’t trust that the other party will share on general principle, but we do trust that they will honor the value of our dollar bill or clay envelope, as the case may be.

Now it is true that the state had some concern for the plight of the debtors, and it was written down in the codes that in certain years all debts would be forgiven, which is sort of hard to imagine in the modern world. But the rise of great families of finance like the Babylonian Egibi, which thrived for over 5 generations and whose loans are recorded in thousands of surviving clay tablets, suggest that creditors did very often recover their money, with interest (Ferguson, 31).

Why Precious Metals?

We know all of this from the cuneiform that has survived. We know a lot less for other cultures. For example, China invented a completely separate system of money, but not one of my sources has been able to give me a detailed account of its early origins, and it’s the same in India. What is common across these three cultures is that they all hit on using precious metals as the money initially. The idea spread out from there.

But remember, we’re still talking about metal by weight, not coinage. It didn’t matter if the precious metal happened to be shaped into a ring or a statue or whatever, just so long as it weighed a certain amount. One fun fact if you’ve been to Sunday School is that the 30 pieces of silver that the sons of Israel collected for selling their brother Joseph into slavery is a later translator’s misperception. In a time of coins, the translator assumed they must have meant 30 silver coins (that is, pieces of silver). But for the time period in question, it almost certainly meant any number of pieces of silver weighing out to 30 units, the units being whatever units were generally agreed upon at the time.

Why precious metals? Well, other choices were certainly possible. Explorers like Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta reported a vast array of other items used as money around the world. Salt was a common one. Cowrie shells was another common one. But that’s just the beginning of the list. Shellfish, clams, cloth, huge stones, wood, feathers, and even human skulls get reported too. In general, these explorers with a European, Chinese, or Arabic, generally believed that these were primitive systems of money used by cultures who were not intelligent or developed enough to have thought of coins. But on closer inspection it turns out that calling some of these things money is misleading because they were not always used in the same way that Europeans, Chinese, and Arabs use money.

For example, the Lele people in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo used cloth woven from raffia, which they exchanged amongst themselves and also an official exchange rate of 10 francs per cloth when they were ruled by Belgium. However, though European visitors thought of it as money, the Lele mostly exchanged goods by social status, not purchase. Cloth was only used as payment to the highly skilled craftsmen to whom you were not related. More commonly, it was given away to reinforce social relationships, such as a reward for new mothers or as a fine for adultery (Williams, 208-209).

The Lele people of the Congo used raffia cloth as currency. But like many cultures around the world, the currency was not always traded for the same reasons that modern people use money, leading many scholars to question whether “money” is the right word for it at all.

Image from the British Museum

But if you are going to use money in the sense we are more familiar with, then precious metals have a lot of advantages: They are somewhat rare, which restricts the supply, but they are not so rare that there is no supply. They are durable. They do not rot or get eaten by pests. They can be easily subdivided. They can be melted down, reshaped, and stamped with the official seal of the government.

That last bit is by no means trivial. When Alexander the Great conquered Persia, he needed half a ton of silver per day to pay his army, and that certainly wasn’t coming from Greece. Nope, it was coming from Persia itself as he captured their silver mines. In Mesopotamia, he wiped out the native forms of money and insisted on coins with himself on it. Modern money there wasn’t naturally evolving. It was enforced by the invader, a way of solidifying control (Orrell, 23).

In 175 BCE, the Chinese emperor decided to relinquish control of money. Everyone was allowed to mint money, his purpose being to increase the money supply. Unfortunately, the ruler of the Wu province had greater ore deposits than the others allowing him to become as rich as the emperor. This obviously wouldn’t do, and the monopoly on money was reclaimed by the central government, with the economic advisor noting that with a unified system, “the people will no longer serve two masters” (Orrell, 32).

The point is that our modern money system which we both love and hate is not a naturally evolving thing, the inevitable endpoint of civilization. It is a carefully controlled creation of the state itself, inextricably tied with politics.

Other Options for Life Without Money

Not every state has felt the need for it. The Inca didn’t use it. They had a successful planned economy. You contributed your labor. You got food, clothing, and your other needs met in return. They certainly had gold and silver, but they were completely perplexed by the value the Spanish placed on it. “Even if all the snow in the Andes turned to gold, still they would not be satisfied,” complained one of the Inca (Ferguson, 21). And he had good reason to complain. Pizarro’s dealing with the Inca was double dealing from the word go and subsequent history only got worse, as massive numbers of Indians were enslaved in mines that were basically a death sentence (Ferguson, 23).

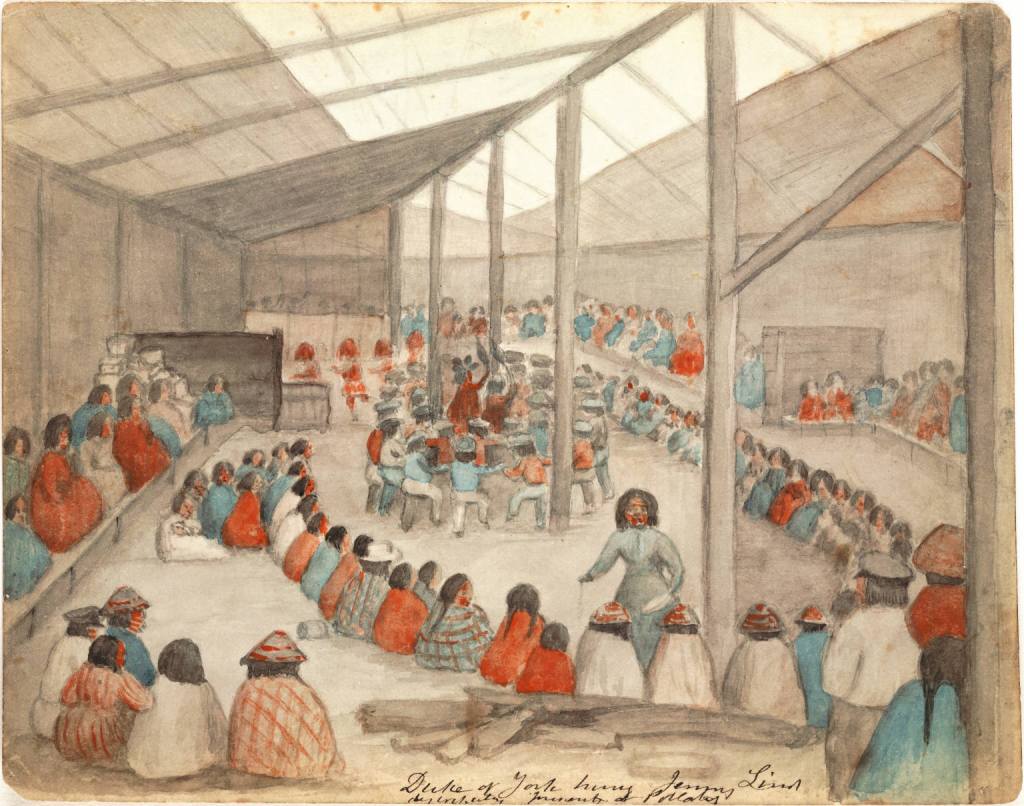

Other indigenous peoples also had trouble coping with the concept of money. Many tribes in the Pacific northwest had a ceremony called the potlatch. It took different forms in different tribes, but essentially it amounted to different leaders of the community giving away massive quantities of goods. The more you gave away, the higher your prestige, so it was of value even if it meant your financial ruin. Sometimes the goods were even ceremonially destroyed. Westerners were appalled. Where’s the intelligent self-interest that drives the economy? What about saving for a rainy day? And destroying the goods was such a waste! The potlatch was banned for decades in a top-down effort to force these tribes into Western economic views.

A potlatch was way of redistributing goods, with no money attached used by Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest. In this watercollor of the Klallam people, a woman is giving gifts to the people gathered.

Image by James Gilchrist Swan (1818–1900)

Now I don’t mean to paint these societies in too rosy a light. In the Inca empire, the penalty for laziness or refusal to contribute your labor was death. And money has created economies that provide many people a standard of living enormously beyond the wildest ideas of people in the past. But while we are dreaming of pay raises and calculating our retirement savings, it’s worth remembering that things don’t have to be like this.

One chief of the Tonga Islands put it this way:

“If money were made from iron and one could make knives, axes and chisels with it, then there could be some point in giving a value to it, but as it is I see no value in it. It a man has at his disposal more yams than he has need for, then he can exchange them for pigs or bark cloth. Of course money is easy to handle and is practical, but, as it does not rot, if it is preserved, people put it aside instead of sharing it with others (as a chief should do) and they become selfish. On the other hand if food is the most precious possession a man has (as it should be the case because it is the most useful and necessary thing) he cannot save it and one will be obliged either to exchange it for another useful object or share it with his neighbors, lower chiefs, and all the people in his care, that for nothing without any exchange. I know very well now what makes Europeans so selfish—it is money.”

Finow, Chief of the Tonga Islands, quoted in Cribb, 216-217

Like it or loathe it, most of us do now live in a world dominated by money, and in the coming weeks I’ll take a look at how women have fared under that system. I will not be covering all the possible topics. The wage gap, for example, made me feel depressed just thinking about it. But I will talk about women and credit, women and the GDP, women and marital property, women and taxation without representation, and women in high finance. And next week I’ll lead out with Women on the Currency, and why when you pull out your wallet and take a look at the money, you probably aren’t looking at a picture of a woman. Unless you live in the British Commonwealth, of course.

Selected Sources

Cribb, Joe, et al. Money : A History. London, British Museum Press, 1997.

Ferguson, Niall. Ascent of Money : A Financial History of the World. S.L., Penguin Books, 2019.

Orrell, David, and Chlupatý, Roman. The Evolution of Money. New York Columbia University Press, 2016.

[…] earliest foremothers didn’t do shopping for the most part. I talked about this in episode 3.1. Most tribal societies were all about relationships, not transactions. So when I’ve got a […]

LikeLike

[…] if you remember episode 3.1 on the early history of money, credit is as old as civilization itself. The Sumerians had it. The […]

LikeLike