Pull out your wallet. Get out all the bills and all the coins.

If you’re me, you’ll be lucky to have any bills, since I’m a plastic all the way kind of payer. But if you are the type of person who has bills or coins, guess how many female faces you’ll be seeing on those coins? Answer: well that depends on what country you live in, but I feel fairly confident that unless you live in the British Commonwealth that you’re mostly looking at men. By one estimate, only 8% of the world’s banknotes depict women. Once upon a time, that was not true, largely because once upon a time the money didn’t depict human figures at all, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

Coins in Ancient Greece

As we talked about last week, the early use of precious metals to pay for stuff meant you measured out your gold or silver by weight. The first folks to decide they could do without all that weighing and measuring nonsense were the people of Lydia in about 600 BCE. Lydia sits in what is now Turkey, but was tightly connected with the Greek city-states. Their coins were made of electrum (a natural alloy of gold and silver) and featured animals or inscribed names on them (Cribb, 23). By all accounts, this made them extremely wealthy, and if you’ve heard the phrase rich as Croesus, that’s because Croesus was the Lydian king holding all this electrum. As far as I can tell, no women were depicted on any Lydian coins, but that’s okay because men weren’t either. In general, the coins have punches on one side (presumably to mark the amount, though I’m not sure about that). On the other side, they often have a figurative design, such as a lion, stag, or ram. Historians don’t fully understand these figures. The lion was associated with Lydia, and some of the others are associated with other city-states. But occasionally there is a name of a person, such as one that says “I am the sign of Phanes.” That one has a stag, so perhaps that was his personal symbol, like a coat of arms? Who knows? (Cribb, 24)

As the idea spread, many Greek city-states produced their own coins and it became common to stamp them with something to identify the community that had made it. And that means that some of the earliest and most influential coins do indeed feature a woman, albeit a mythological woman. Athens, the dedicated city of Athena, put the head of their goddess on their silver tetradrachms, also known as owls because they featured her sacred bird on the reverse side (Cribb, 27, 30). The Athenian owls were remarkably long lasting as currency, with more or less the same design being used from the late sixth century until the first century BCE (Cribb, 30).

Athenians didn’t invent coins, but they had some of the most successful, and they featured a woman (albeit a mythological one). They had Athena on one side and her sacred bird on the reverse side, which gave them their name. Athenian owls were remarkably long lasting as currency, with more or less the same design being used from the late sixth century until the first century BCE.

Image by Numismati – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

The idea of coinage spread, as did the idea of inscribing them with religious figures, and as long as that was true, women made a reasonably good showing, particularly since Athens was so financially successful and produced a lot of coins. But Athena is not alone. Eretria inscribed their coins with Artemis, goddess of hunting, nature, and virginity; Smyrna had some with Tyche, goddess of fortune and luck, Gozo had some with Astarte, the Phoenician moon goddess (Cribb, 46).

Of course it wasn’t very long before rulers realized that using wealth to honor the gods is all very well, but using it to honor the living, breathing, and most importantly tax-collecting rulers themselves is even better. Increasingly, the gods and goddesses began to get edged out to make way for the ruler of the day, and so quite naturally, the prevalence of women drops way, way down. But not to zero. In Ptolemaic Egypt where husband and wife were co-rulers, we get coins that feature both partners (Cribb, 36). Cleopatra’s, of course, featured her alone.

It didn’t take Mediterranean rulers long to decide that using their own image was way better than using a god’s. As a result, most coins featured men, but there are exceptions, as Cleopatra proved here.

Image by PHGCOM – Own work by uploader, photographed at the British Museum, Public Domain

Coins in Ancient Rome

Rome was a rising power too, and as in so many things, it took the Greek’s coin idea and ran with it. And yes, their coins did feature women, and what’s more they were sometimes the kind of woman born in the normal way, rather than the sprung-from-the-head-of-Zeus type of woman. Rome may not have been much for putting women in the top job (there never was a Roman empress who ruled in her own right), but they were more egalitarian than the Greeks had been, not that that’s saying much. The wives, sisters, daughters, and lovers of the emperors were powerful figures and they do appear on some of the coinage: Fulvia, Octavia, Livia, Julia, first and second Agrippina. All these women and more can be found on surviving Roman coins.

The occasional Roman woman got a coin too, like Fulvia Antonia, wife of Marc Antony.

I don’t mean to say that Roman women got equal representation or anything ridiculous like that. Far from it. Emperors like Augustus, Nero, and Vespasian were all quite fond of their own images, and it is sort of interesting to see the images they approved. Augustus looks like the class nerd. Vespasian looks like a retired football player gone to seed. Nero looks not fully human, though he does have some nice hair ribbons (Mudd, 16-17).

The sheer volume of coin production in the Roman world was amazing. Hundreds of millions of coins in the 3rd and 4th centuries alone, a quantity that was not repeated until modern times (Cribb, 51). Even the word money has a female tie-in, as the word itself comes from the Roman goddess Juno Moneta. In ancient Rome, coins were minted in her temple, and she appears on some Roman denarius coins at least from the first century BCE (Feingold, 62).

Even the word “money” comes to us by way of a Roman goddess. This is Juno Moneta. Roman coins were minted in her temple.

By Geni

And what was the purpose of all this money? Was it to build aqueducts to bring water to the masses? Was it to build ships and roads for distributing the great wealth of the empire? No, of course not. It was for paying the army. In the heyday of the empire, the army was ¾ of the entire imperial budget (Cribb, 51), which, by the way, may make you feel a smidgeon better about the size of the Department of Defense, if you get bothered by that sort of thing. Incidentally, the Athenian owls were also largely for paying the army back in Greek times. Military power and money power go hand in hand.

Why Coins at All?

One question is why the coins were so successful. People had been doing things by weight since at least 2000 BCE. No less a person than Aristotle himself suggested that the switch to coins was made for reasons of convenience, to save all the trouble of weighing out the silver every time. That sounds so logical, one has to wonder why no one thought of it in the previous fifteen hundred years (Cribb, 27).

As with any new development, it is also questionable how much money circulated in the lives of ordinary people. Did your average housewife pay at the market with gold and silver? Or was she bartering her butter and eggs for meat and vegetables? We don’t always know, but certainly by the Common Era, coins were ubiquitous and commonplace even for ordinary people in the Roman Empire. We’ve got this from a number of sources, including the Bible. Jesus’s stories, told to ordinary Judeans are full of coins (the Good Samaritan, the poor widow and the alms box, the woman and the lost coin, render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s, I could go on, the coins are all over the place in the four Gospels), and these coins are often handled by women.

People outside the Mediterranean also knew a good idea when they saw one, and the idea caught on in the surrounding regions and stayed. The Visigoths minted coins, which are basically Roman. Some of the earliest Islamic coins were made in imitation of Byzantine coins and featured the emperor, but the disapproval of images meant that they were quickly replaced with geometric patterns or calligraphy (Williams, 95), some of which are absolutely beautiful in a way that no squinty-eyed, hook nosed king on a coin has ever been. But of course, that means there aren’t any women to be found on their currency either.

Coins in Asia

If we go farther afield, we can find other coinage traditions outside the Lydian model. Indian coins date back to the 6th to 4th centuries BCE (Cribb, 111). The earliest coins featured animals, plants, religious symbols, everyday household objects, and a great many geometric patterns with no clear meaning. Notice the lack of human figures, so again, no women. When Alexander the Great arrived, the Greek influence is clear, which means that the tradition of Indian coins is somewhat hard to disentangle from the Greek, even though they very definitely did have their own before the Greeks arrived. Perhaps because of the Greek influence, they did cotton on to the human figure idea, and while most of the depictions are of the male gods in the Indian pantheon, I have seen a picture of a gold coin from about 350 CE featuring Lakshmi, goddess of wealth, fortune, and prosperity (Cribb, 118).

The Mediterraneans were not the only ones to use coins. This Indian coin features, Lakshmi, goddess of wealth, fortune, and prosperity.

Image by Uploadalt – Own work, photographed at the British Museum, CC BY-SA 3.0

The Chinese, on the other hand, get a tradition all their own. Curiously, their coins also date to the 6th to 4th century BCE, so there was obviously something weird in the world atmosphere at that point since we have three disparate cultures inventing coins at pretty much the same moment. The most famous Chinese design lasted until the 20th century, and they have a total lack of female figures on them, for the obvious reason that they don’t have any figures on them at all. Instead, they feature Chinese characters which once referred to the weight of the coin and later including the period of issue and other things (Cribb, 135). But no people, divine or otherwise. What’s really cool about these coins is that they have a square hole in the middle, which allows you to string them together, often in strings of 100 or 1,000. Which is brilliant? Why didn’t Western coins do that? Though I admit, it would have put a damper on so many king’s self-promo campaign. Probably would have helped in Nero’s case. We don’t get a person on a Chinese coin until 1912 when Sun Yat-sen does it (Cribb, 143).

Paper Money

While there is a curious synchronicity between the dates of the first coins in Greece, India, and China, paper money is a different story. Much later, of course, and the Chinese were way ahead. The main rationale for paper money was a shortage of metal, so it depends on whether the country currently has a metal shortage. China had them in the 7th century AD and then again in the 10th century. But crucially these attempts had expiration dates and included a promise to redeem them in coins. So it’s really much more like an IOU than a dollar bill. In 1189, the Jin dynasty got rid of the expiration date and shortly thereafter that Mongol dynasty used paper money exclusively and banned coins entirely. Paper money solved several problems, like the exchange problem between regions that used different coins (Cribb, 148), and the metal shortage, and just the sheer weight of large amounts of money. What it didn’t solve was hyperinflation, so that’s another reason that they come and go (Mudd, 22). And again, the notes don’t have any figures on them. Only characters, so no women. Same with those I’ve seen from the Japanese clans (Mudd, 64).

Europe didn’t catch on to paper money until much later. Marco Polo reported Chinese paper money on his return to Europe, but the idea was ahead of its time in Europe. While IOUs of various sorts circulated in fits and starts, the first freely circulating banknotes came from the Stockholm Bank in Sweden in 1656. It’s got lots of text and no picture, other than the ornate border around the edge (Cribb, 180). It flourished for a few years and then failed for a predictable reason: too many notes issued, the bank ran out of reserves, a crisis of public confidence (Mudd, 24). The old story.

What’s mostly noticeable about banknotes over the next several hundred years is how many designs there are, given that banks issued them themselves, often in whatever amounts they wanted, which is part of the reason that so many failed.

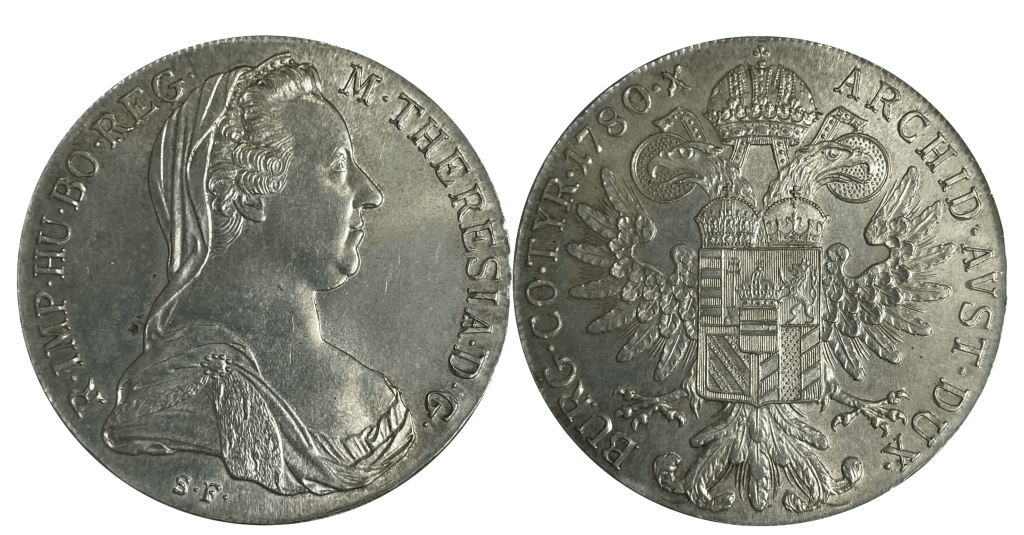

Coins were also subject to inflation, but they were much more reliable, having some inherent value in themselves. In the years after the collapse of the Roman empire, Europe just continued the Roman coin tradition. Lots of rulers on coins. So they’re men, except when we happen to get a woman in the top job. So we’ve got coins with Elizabeth I of England on them. Maria Theresa, Empress of Austria, was on coins for Austria of course, but since we’re now into the age of empire, her coins were used in Ethiopia and Arabia (Cribb, 195). And of course the sun never set on Queen Victoria’s coins.

Coins became more and more exclusively for demonstrating the power of the current ruler. And so we have women on coins only when a woman happened to be in charge, like this one of Maria Theresa of Austria.

By Windrain – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

Coins in the New World

If we turn our attention to North America, we get several radically different stories. Mexico was no slouch for centuries when it came to currency. The reales, later named the peso, was the dominant silver coin internationally until the end of the 19th century (Feingold, 78). It was used as far away as China. This was because Mexico was so blessed with silver deposits. It also meant that they had pretty much nothing in the way of banknotes because why do that when silver is so available?

Further north, it was a different story. The eastern half of the US and Canada has pretty much zip, zilch in the way of precious metals. Colonial governments found themselves strapped for cash almost immediately and banknotes were the way forward. Massachusetts had the West’s first government-backed paper money in 1690. And what was the money for? Oh yes, paying the army, of course. The government needed soldiers for the French and Indian war, and they had no metals with which to pay. Some things never change.

In the Revolution, the Continental Congress printed many, the British cleverly counterfeited them and flooded the market, value plummeted, and that is just one of many banking problems in early American history. Those continentals had seals with various animals and other designs, but no people, as far as I can tell.

Some of the earliest women to appear on American money were not specific women at all, but rather personifications of an idea. Lady Liberty is most famously recognizable in the Statue of Liberty. She also dates back to Roman times where she appeared on Roman coins as the goddess Libertas. The first official coinage under the constitution of the USA was the Silver Liberty dollar of 1795, and it featured Lady Liberty (Cribb, 225). She has appeared on many subsequent American coins, including the double eagle, or 20-dollar coin, made in 1907, and often considered to be the most beautiful American coin ever made (Feingold, 78). We also see Lady Justice, who holds scales and often has a blindfold. She dates back to Roman times as the goddess Justitia. She appeared on American money at least as early as 1863.

Personifications of Women

Other countries also go in for the woman as personification of an ideal. Brazil has a sculpted female head as the personification of the Brazilian republic. She is on many, if not all of their notes (Mudd, 124). The French West African notes of 1945, showed an unnamed African mother and child, embraced by Marianne, the symbolic figure of France (Cribb, 194).

The first nonmythical woman to appear on US federal paper money was Pocahontas, who was on the $20 bill at a few different points in the 19th century. However, if you want to consider Confederate money, then Pocahontas is narrowly edged out of first place by Lucy Holcombe Pickens, the Queen of the Confederacy.

In 1896, the US issued a series of neoclassical notes, with female personifications of History, Science, Steam, Electricity, Commerce, and Manufacture (Feingold, 89), not all of which I would have drawn as a woman had I been given the job, which fortunately for everyone concerned, I wasn’t. The one-dollar note in that series also featured both George and Martha Washington on the back. Incidentally, there was a large numeral 1 between them, indicated that it was a one-dollar bill, and that sparked some smart aleck complainers to quibble with the design, saying that “no one should come between George and Martha.”

Martha Washington has appeared on several U.S. banknotes, including this 1896 version which prompted some smart alecks to quibble with the design, saying that “No one should come between George and Martha!”

Image from Wikimedia Commons

The 20th Century

The American coin tradition adds only a few other women. Sacagawea was the face on the millennium dollar coin in 2000, one of only three historic women shown on American coins (Feingold, 81).

Very few women have appeared on U.S. coins, but Sacagawea and Pocahontas are among them.

By United States Mint, Pressroom Image Library

To tell the truth, the American money tradition got rather stuck in a rut in the 20th century. Our currency is extremely stuffy, extremely tradition bound, and we generally only believe in honoring past political heros. If you only do politics, that pretty much means you only do men. Other countries, though, are not so stuffy. Not only do they know about colors other than green, but they also know about subjects other than politics. So, for example, the 1998 5000 pesos note from Chile features Gabriella Mistral, a poet, educator, diplomat, and feminist (Mudd, 129). The 2000 200-peso note from Mexico has Juana Ines de la Cruz, the 17th century nun and writer (Mudd, 152). The 1996 twenty Kronor note from Sweden features Selma Lagerlof, first woman to win the Nobel prize for literature. The 1995 Swiss 50-franc note has Sophie Taeuber-Arp an abstract artist.

These last two European examples, went by the wayside, of course, when the euro was introduced because they’ve gone for architecture rather than people on the notes. On the coins, it’s a different story since each country gets to have some with their own design. So you sometimes get Bertha von Suttner, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, or Marianne personification of France, Latvia has an anonymous maiden, the Netherlands puts on Queen Beatrix, and we’ve even gone back to our roots and gone for goddesses, as the Italian 10-cent coin features Venus, by Botticelli. You might say that that is no where close to 50% of the countries in the euro zone, and you’d be right, but bear in mind that many of the countries don’t use people at all. My personal favorite is Ireland’s, which is a harp.

And the idea of using the currency to promote your country’s brand is now indelibly marked on the rest of the world (except in the US of course, and also possibly in the British Commonwealth where all of the money has featured Queen Elizabeth II for a long, long time). So Japan issued notes in 2003 and 2004 featuring Ichiyo Higuchi and then Murasaki Shikibu, both famous female writers. This ended something of a drought in Japan, as prior to 2003, the most recent woman to appear on a yen note was Empress Jinggu in 1881 (Mudd, 62). The 1993 Australian 10-dollar note also features Dame Mary Gilmore, a poet and activist (Mudd, 163). I could go on, but I’m getting bored.

Japan had a long drought of women on banknotes, but they ended that in in 2003 and 2004 with Ichiyo Higuchi and then this one with Murasaki Shikibu.

By Bank of Japan. The illustrations on the bank note are paintings from 12th and 13th century scrolls. – Bank of Japan, Public Domain,

Since the rise of democracy and especially since the rise of communism, there is a small undercurrent trend to show not a great leader or creator, but the common man and occasionally, also the common woman. So they are unnamed, and also generally shown as working hard. In India, for example, one note shows Gandhi leading a group of followers the first of which is a woman. On another in an allegory of the Indian economy, a group includes a woman at a computer (Mudd, 85). The 1963, the Equatorial African States (still controlled by France) had one with women carrying their baskets on their heads (Mudd, 101). The Democratic Republic of Congo has one of a man and woman working in a field (Mudd, 105). The Eastern European and communist block countries issued notes that generally featured strong, effective workers. And women were included in that. For example, the Czechoslovakian 100 koruna note of 1961 shows a female farm-worker (Cribb, 242). These are just examples, of course, there were plenty of others.

Islamic countries began to open to Western forms of money when the Ottoman Empire fell at the end of World War I and within a few decades, it turned out that even the most conservative countries could allow people on their coins after all, which I have to say is a great pity, because the calligraphy was so beautiful. So for example, Egypt has one with Nefertiti on it, but she is the only woman I have located, though I admit I have no comprehensive source on this. I could be wrong.

The 21st Century

Looking forward, there is a strong push to get Harriet Tubman on the American $20 bill. It was supposed to happen in 2020, but yeah, that didn’t happen. In theory, it’s still in the works. If it happens, she would be one of the first women to appear and definitely the first African-American woman to appear, which is a victory that means a lot to many people.

As an interesting side note, while we haven’t yet had a named African-American woman on the US money, we have had the signature of one. Azie Taylor Morton was the U.S. treasurer under the Carter administration, so her signature appears on all bills printed under that administration.

Many people have pointed out that the U.S. has not yet featured an African-American woman on our currency. But they may not know that we have had an African-American woman’s signature. Azie Taylor Morton was the U.S. treasurer under the Carter administration, so her signature appears on all bills printed under that administration.

As another interesting side note, I’ve also read an argument that says Tubman wouldn’t want to be on the bill, on the grounds that US federal currency is a representation of inequality and the kind of immoral capitalism that allowed slave markets to flourish.

Whatever you think about that issue, there is also a cynical line of thought that claims it doesn’t much matter. By one estimate cash in people’s pockets is only 11% of the American money supply (Ferguson, 29). I myself rarely use cash. By 2023, Sweden plans to go completely cashless. One presumes in our increasingly digital world, others will follow. And the bits in the computer are even more abstract than the obscure markings on early coins. For sure, there won’t be any women depicted on them. And certainly, who is on the currency is an entirely symbolic issue. Far more important is whether people have equal access to earn and use said currency.

Selected Sources

Cribb, Joe, et al. Money : A History. London, British Museum Press, 1997.

Feingold, Ellen R. Value of Money. Washington, D.C., Smithsonian, 2015.

Ferguson, Niall. Ascent of Money : A Financial History of the World. S.L., Penguin Books, 2019.

Mudd, Douglas, and Smithsonian Institution. Mudd : The Art and History of Paper Money and Coins from Antiquity to the 21st Century. New York, Collins, An Imprint Of Harpercollinspublishers, 2006.

[…] was on Women and Their Money. I asked ChatGPT to tell me (in the style of comedian Ellen DeGeneres) what women have been on the currency. If you notice a distinctly Anglophone slant to ChatGPT’s response, yes, yes, that’s one of […]

LikeLike