The financial sector is one I never ever considered entering professionally, which is a real shame because I bet they make more money than people who just like to read history. But reading history books has allowed me to share with you some statistics on the subject of jobs in high finance. The number of otherwise intelligent people entering finance as a profession has ballooned in the last few decades. According to Niall Ferguson, professor at Harvard, the percent of Harvard men who went into finance in 1970 was 5%. By 1990, it was 15%. Now setting aside the issue of whether these people actually make a valuable contribution to the world (unlike say, history podcasters whose contribution is priceless), but my question is what about Harvard women? According to Professor Ferguson, the percentage in 1970 was 2.3% and it rose to a walloping 3.4% by 1990 (Ferguson, 5).

If we look at ratios of women to men that is actually a serious drop for women. In 1970 we were at nearly 1 in 2. In 1990, we were at just barely 1 in 5! So much for women’s equality and all that.

Now maybe it’s all different down at Yale, but I doubt it. Women’s ability to enter this field has been fraught with difficulty, and today I am going to tell you about one of the earliest American women to do exactly that.

Born to a Whaling Family

In 1834, a little girl named Hetty was born to Edward and Abby Robinson, a Quaker family in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Edward was a stalwart member of a family that led the area in whaling and banking. Wealth was the visible proof of God’s blessing on his righteousness, and goodness knows he had that. New England was, as yet, untroubled by thoughts of population extinction, biodiversity, and the health of our oceans, whaling was good business. In a town where owning an 1/8 share in a ship meant you were well-fixed, Hetty’s family owned 30 ships outright, with partial shares in many others. What Edward Robinson did not have was a son. Like so many girls before her, Hetty was the wrong gender, and when a younger brother was born, he died as an infant. Abby retreated into depression and ill health. Neither was glad to see their daughter.

Hetty spent her childhood in her grandfather’s home, who also was not glad to see her, until she got old enough to read, at which point he set her to reading aloud the stock quotations and the commerce reports. Later he had her help with his business correspondence and promised he would leave part of his fortune to her. In a world without much love, it was clear to Hetty that the purpose of life was to get money and affection is expressed in dollars and cents. At the age of 8, she gathered up what she had saved from her weekly allowance, got a ride into town and opened a bank account so she could earn compound interest. Her family was proud.

When her grandfather died, Hetty moved back to her father’s house, where she watched as he assessed his inventory, inspected ships, negotiated with captains and merchants, and kept the books. Nevertheless, she was a girl, and she was also taught dance, piano, needlework, and the social graces. The problem was that New Bedford was small, suitors were few, and the daughter of Edward Robinson couldn’t marry just anyone. So eventually, he packed Hetty off to New York to live with a relative who could introduce her into society. He gave her $1200 to buy clothes and make herself presentable. Hetty had a good time in New York, attending parties, dances, balls, and teas, but she didn’t get married. And she got tired of all the excess and soon returned home. Robinson was surprised. He was also surprised that she hadn’t asked for more money at any point. Society life and keeping up with the Astors must have been expensive? But Hetty answered proudly that she hadn’t needed any more. Of her $1200 she had spent a mere $200 on clothes. The rest she had invested in bonds and was already turning a tidy profit.

In 1860, Hetty’s mother died. She had been heir to a vast estate, which Hetty had hoped to inherit from this distant uncaring mother. But Abby died without a will and it all went to her husband. Hetty was hurt, and she sued, but she didn’t win. Hetty got an $8000 house, but that was small potatoes compared to the bulk of the estate.

Meanwhile, her father had seen the writing on the wall when it came to the whaling business. Kerosene was in, mineral oil was in, whales were harder to find. It was time to sell out, which he did. Hetty spent 1860 living the life of a debutante in Saratoga and New York, including dining with former president Martin Van Buren and dancing with the Prince of Wales, to whom she said that she was the “Princess of Whales,” meaning the ocean mammal. But the good times wouldn’t last. War was about to break out.

Coming of Age

Hetty, of course, was a girl and lived well to the North. The war had nowhere near the impact on her that it would have on millions of others. But war brought financial uncertainty, and that coincided with increasing frailness on the part of Hetty’s aunt Sylvia, who was enormously rich, and to whom Hetty was the only heir. Hetty had expected to inherit a tidy sum from her grandmother and didn’t. And then she expected to inherit a tidy sum from her mother and didn’t. She wasn’t going to let that happen again. In the fall of 1861, she and Sylvia drew up mutual wills. Sylvia’s said that Hetty was her heir, and that the money would go directly to her, which meant that it would not be put in a trust for someone else to manage. It was to be hers and hers alone. According to Hetty, Sylvia also signed a letter to be attached. This letter stated that if she ever chose to write a new will, she would return this earlier will to Hetty, and that if a newer will ever surfaced without this having been done, then the judge should rule based on this earlier one, because any new will would only have been made by her under duress and while not in full possession of her mental faculties. These documents were locked away in New Bedford, and Hetty went back to New York satisfied.

She spent the war years in New York, helping her father with his business, and nursing him as he grew ill. She also pestered his assistant to make sure she would receive all the money due her from that side of the family as well. When he died in 1865, Hetty listened nervously for the reading of the will. Edward Robinson died with an estate of $6 million dollars. Hetty was his only offspring, and she did indeed inherit $1 million free and clear, which would make me plenty happy. But not Hetty because the remaining $5 million were given to Hetty in trust only. As in, she was a girl and so she could not be trusted to manage her own fortune. Years of working by his side had not changed that. It was a third will in which her expectations were dashed.

It was only 3 weeks later when she was summoned to New Bedford because Aunt Sylvia was dying. Hetty went north again for the funeral, and sat nervously listening to yet another will. Sylvia had an estate of $2 million. And as the will was read it turned out that only $1 million would go to Hetty, the rest was distributed to various friends and charities, including enormously generous payments to her doctor and his wife and his daughters. Even Hetty’s $1 million were left to her in trust, because yep, she’s still a girl. Still can’t be trusted to manage the money.

A livid Hetty ransacked her aunt’s trunk and produced the earlier will and the letter saying that it should take precedence over any later will. She visited her attorney and claimed that the physician had drugged her aunt with laudanum to get her to make that newer will. She tried to bribe the probate judge to rule in her favor. When none of this worked, she took her case to the Massachusetts Supreme Court.

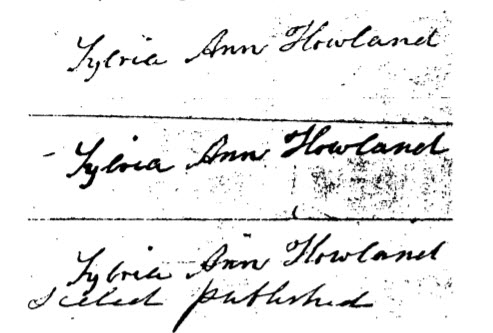

The crux of the case hinged around the signature on the letter, which upon examination proved to be identical to the one on the will. To this day, the Howland will forgery case is cited as possibly the earliest American court case to use statistical probabilities as evidence. Because while it is highly unlikely that a person would sign their name exactly the same way twice, it is not impossible. John Quincy Adams was known to have multiple signatures that looked traced, but were not. Expert witnesses were brought in on both sides. Professor Charles Peirce of Harvard University testified that the odds of the signature being genuine were one in 2,666 of millions of millions of millions. More recent statistical analysis has indicated that he was off on his own mathematics here (Meier, 498), but the point remains that it’s highly unlikely. On the other side, celebrated scientists like Oliver Wendell Holmes, and Louis Agassiz examined the signature and found no indications that it had been traced.

It would be nice, if with the benefit of 150 years of hindsight and developed science we could say with certainty whether Hetty forged her aunt’s signature, but we cannot. The signatures still exist, and I have posted them on the website. They do look awfully similar. But probabilities are not certainties, and Hetty denied the charge to her dying day. All we can know for sure is that Hetty did not win her case. The judge declared a mistrial on a technicality. And in the appeal (of course Hetty appealed), the parties compromised.

And speaking of the forgery case, what is your opinion of the signatures on the left? The first is indisputably Hetty’s aunt Sylvia’s. But the following two are disputed. Do you think Hetty forged them?

Source: from the Meier article listed in the sources below

Moving On and Out and Up

In the midst of all this tumult, Hetty got married. Edward Green had been approved by her father, prior to his death, and despite quarrels, feuds, and a court case, they tied the knot in 1867. Now Hetty may not have had all the money she wanted, but one of the reasons why her interminable court case was off putting to so many is that she was a fantastically rich woman even without Sylvia’s fortune. By one calculation, Hetty was earning on the order of $1000 per day when you counted up the revenue from all the various trusts, plus the part she was allowed to manage (Sparkes, 119). It’s hard for us normal people to feel too sorry when someone in the 1% loses out on a deal, right? And indeed, the negative press was enough that Hetty felt her safety was in question. The newlyweds soon packed up and moved to Europe.

Living abroad did not dampen Hetty’s quest for money. She bought bonds at a discount and earned dividends. Her father had taught her never to borrow, and she didn’t. Her trick was to always keep cash on hand, so she could buy railroads and real estate when they were low and unwanted, and then sell later when the price had gone up. The strategy worked for her. Her personal best was $200,000 in one day. And that’s $200,000 in 19th century money! I’d take that amount even in today’s money.

None of this wheeling and dealing stopped Hetty from performing the more traditional women’s roles. In 1868, her son Ned was born and Hetty stated that she planned to make him the richest man in America. In 1871, her daughter Sylvia was born, and upon questioning Hetty snapped that of course, she didn’t forge that signature. Why would she name her daughter after a woman whose signature she had forged?

After seven years, the Greens packed their bags and headed back to America. The Panic of 1873 had dried up the money market in Europe. Edward’s personal fortune was in jeopardy, as were so many others. But Hetty had other things on her mind. She visited her bank herself, depositing a wad of cash and a pile of certificates. Investors right and left were abandoning their stocks, and to Hetty that sounded like a good time to get in. “When I see a good thing going cheap because nobody wants it, I buy a lot of it and tuck it away,” she said. Brokers all over Wall Street sighed with relief to see her and (her fortune) come back to New York.

Other people were not so pleased. When she and Edward made a trip to his childhood home in Bellows Falls, the people turned out to see the millionaire wife. They expected opulence and grandeur. They got a plain-faced, plainly dressed woman who quarreled with her mother-in-law over household expenses. She enjoyed bargaining for a good deal, but for tradesmen who had far less than she did, it seemed stingy and mean. Edward’s investments were turning out badly, and he had to borrow money from his wife to keep afloat.

Which brings me to an interesting point, which is: why were their finances not already lumped together and under his management? That would have been entirely normal. The mere fact that borrowing from his wife was a possibility suggests that they had a different arrangement. There have been rumors at some points that there may have been a pre-nuptial agreement involved, but other historians doubt that, in part because of events that happened later. It has also been said that Hetty’s father left her his money on condition that Edward could not touch it. But her father’s money was only a part of her fortune. Whatever the arrangement, Hetty certainly considered her money as separate from his. She gave him advice on his investments. He often ignored her. And he often lost. There’s a lesson in there somewhere, but I’m sure I don’t know what it is.

Meanwhile, Hetty was doing well with her money, gobbling up real estate and railroads, but it is often not possible to fully trace her movements. She sometimes purchased under false names. She held her game close to the chest. Other investors were often unsure what she was up to. But she didn’t always win.

Hetty stored much of her money at the Cisco bank, and her deposits in 1885 included half a million dollars on deposit, plus $26 million in stocks, bonds, mortgages, deeds, and other goods. All this would have been fine, except that in 1885 the Cisco bank was in trouble. John A Cisco was also Edward’s banker and his partner in railroad investments of their own, which were quickly going south. Hetty had no intention of being caught up in the fall. She wrote a letter: “Please close my account and remove my funds of $550,000 dollars on deposit as I wish to transfer them to the Chemical Bank.”

Cisco said no. He countered that Edward owed the bank over $700,000. Hetty said that was no affair of hers. Her money and Edward’s was separate. Cisco announced that the bank would close.

Hetty bundled herself in black wool dress, black cape, black bonnet, and black gloves, took a cab to the bank, and marched in. “I’ve come to get what’s mine,” she declared.

But it didn’t work. The next day she came back. She cried. She screamed. She stamped her foot. Random people walking by on the street stopped to watch the fun through the windows.

In the end, Hetty paid Edward’s debt. And this is the main reason why some historians doubt that she had a prenuptial agreement: it doesn’t seem like to her to have paid a debt if she genuinely had a document saying she wasn’t responsible for it. But she also didn’t let it pass gently. She removed her $25 million of certificates and deposited them elsewhere. She would never forgive or forget the men who had caused the problem, up to and including Edward. She didn’t believe in divorce and they remained friends, but they no longer lived together. And she stopped introduced herself as Mrs. Edward Green, which was the standard naming convention of the day. She was now Mrs. Hetty Green, thank you very much.

And if she had always been serious about her work, it was redoubled now.

Those who wanted a billionaire to be opulent were disappointed in Hetty Green. She preferred simple black clothes at all times. Many of her critics said her clothes were so worn through a maid would be above wearing them.

Image from Wikimedia Commons

An Independent Woman of Finance

At her new bank, she refused a private office, but arrived every day to take an empty desk or even to sit on a floor. She refused to wear a corset. She wore only black clothes, and even those were said to be of a quality that a lady’s maid would trash. To prevent colds, she ate baked onions, which had the additional virtue of being cheap. All morning she read newspapers and journals. She studied costs, analyzed risks, interviewed colleagues, and invested money. At lunch she ate oatmeal or a sandwich she had brought with her. She lived in boarding houses to avoid the time and expense of keeping her own house. When told that transferring 1 million dollars of stocks from the New York to Philadelphia office would come with a $100 transfer fee, she said that was ridiculous, bought herself a $4 train ticket and carried 1 million dollars worth of stocks in her handbag herself.

She was well regarded by other investment bankers. The Times called her the Queen of Wall Street. Henry Clews, a famous and successful one wrote that Hetty Green’s “unaided sagacity has placed her among the most successful of our millionaire speculators. She is, however, made up of a powerful masculine brain in an otherwise female constitution” which I’m sure he thought was a compliment.

She was also well known to the public, much to her chagrin. She was swamped with letters begging for money, suggesting ransom, or threatening murder. Hetty was afraid. She moved constantly, partly to avoid the press and the public, partly to avoid New York taxes by refusing to establish a residence. Sometimes they lived in Chicago, Vermont, or Massachusetts. One has to wonder how this went down with her kids.

On other subjects, we know exactly how things went down with the kids. Ned and Sylvie were growing up, and Hetty took them along to bank meetings. Sylvie was bored. Ned was excited, but he had a tendency to spend money on Broadway and dabbling with showgirls. Hetty was concerned. She extracted a promise from him: he would not marry for 20 years, which seems just a titch harsh. She packed him off to Chicago and then Texas to learn business firsthand. Her daughter Sylvie was quiet and insecure and not a social success. When one young man did show interest in her, Hetty investigated just like she would a business purchase, and he came up wanting. She told her daughter. “I want you to marry a poor young man of good principles who is making an honest hard fight for success. I don’t care whether he’s got $100 or not, provided he is made of the right stuff. . . I hope I won’t hear anything more about your young man in Newport who knows just about enough to part his hair in the middle and spend his father’s money.” So much for true love.

But as much as she was high-handed about their relationships, she was fierce in protecting them when necessary. In Texas, Ned got into a dispute with another investor over liens on a railroad. The man came to see Hetty on Wall Street to complain, but when he started making threats against Ned, Hetty said, “Up to now you have dealt with Hetty Green, the business woman. Now you are fighting Hetty Green, the mother. Harm one hair of Ned’s hair and I’ll put a bullet through your heart.” And she picked up the gun she kept on her desk.

Besides investing, Hetty also pursued lawsuits. When New York assessed her for $1.5 million in taxes, she swore she was not a resident and produced records to prove she paid her taxes in Vermont. She won. Her antics in court were well known. She was not above making cutting remarks to the judge. On one occasion, she fell to her knees in court and offered a silent prayer before stalking out of the room. She was frequently brought to court by her own lawyers, after she refused to pay them their fees.

Hetty was unapologetic about her methods, and practical in her explanations of why she was a lone woman in a man’s world. In an interview with the Woman’s Home Companion, she said, “A woman hasn’t as many chances for making money as men have. She isn’t around or among men, as a rule, and she doesn’t hear of the opportunities for investment which are talked of day by day, in Wall Street and other financial centers. Most women are afraid to venture into the regions where man reigns supreme. . . I am able to manage my affairs better than any man could manage them, and what man has done, women do. It is the duty of every woman, I believe, to learn to take care of her own business affairs.”

In 1902, Edward Green died. Hetty had long since been disillusioned both as to his faithfulness and his business acumen, which seemed possibly more important to her. But their marriage had lasted nonetheless, and he had been known as “the husband of Hetty Green,” which was hardly the way these things normally went. In what was perhaps the final act on their marriage, Hetty closed up his business accounts, including selling off the stocks in the railroad that had brought him down financially and in her eyes. Typically, she doubled her money in the sale.

Indeed, the main difference between Hetty and many of the millionaire men of the time was that she did not speculate. She bought when the market was low. In boom times, when everyone was buying, she sold. At a profit. When she did buy it was with cash on hand, not with borrowed money, and she believed in thorough research before buying anything. Also, many of these great families like the Astors and the Goulds and the Vanderbilts had at least one (and often more than one) member who was spending money as fast or faster than it came in. Not so with Hetty. She kept her kids on an allowance, and herself on an even cheaper one. This age is known as the Gilded Age, famous for robber barons who lived extravagant lifestyles while their employees lived on subsistence wages. And it is true that wealth was skewed towards the top: 2% of the people owned 60% of the wealth. But bear in mind, that in modern America 1% of the people own 90% of the wealth. Just saying.

Hetty continued her business dealings well into her 70s. But age caught up with her, and she died in 1916 at the age of 81. She was buried in a plain coffin, wrapped in a simple cloth in her chosen residence of Vermont. The funds that she had only held in trust scattered according to the terms of the trust. But that was trivial compared with the fortune she had built herself, and her children inherited some $2 billion dollars in today’s money, which was precisely the legacy that Hetty had wanted to leave.

Image from Wikimedia Commons

One reason Mrs. Hetty Green is not as famous as, say, Mr. Carnegie or Mr. Rockefeller was that she did not give away her money in a big show. This is not to say that she gave nothing away. She did. But not in the same huge and public way. In fact, one of the main ways she helped was that she more than once bailed out New York City. Not by giving them money, she was much too much a business woman for that. But by loaning them millions of dollars well below the established interest rate.

Though she is a poster child for an assertive woman who demanded her rights, her record on women’s rights is interesting. “Every girl should be taught the ordinary lines of business investment,” she said. Or on another occasion, “There is no reason why the married woman should not also be a business woman.” And yet some of her comments would not sit so well with a modern feminist. “I don’t believe much in so-called women’s rights. I am willing to leave politics to the men,” she said, and expressed no desire to see a woman president, and even disparaged the suffrage movement, saying “I haven’t any respect for women who dabble in such trash.”

Hetty continued her business dealings well into her 70s. But age caught up with her, and she died in 1916 at the age of 81. She was buried in a plain coffin, wrapped in a simple cloth in her chosen residence of Vermont. The funds that she had only held in trust scattered according to the terms of the trust. But that was trivial compared with the fortune she had built herself, and her children inherited some $2 billion dollars in today’s money, which was precisely the legacy that Hetty had wanted to leave.

Selected Sources and Images:

My major source was The Richest Woman in America: Hetty Green in the Gilded Age by Janet Wallach.

There are a couple of other biographies of Hetty Green including this much older one from 1935: The Witch Of Wall Street: Hetty Green by Boyden Sparkes and Samuel Taylor Moore.

For an analysis of the statistical arguments in the forgery case, I also consulted “Benjamin Peirce and the Howland Will” by Paul Meier and Sandy Zabell, published in the Journal of the American Statistical Association, Vol. 75, No. 371. (Sep., 1980), pp. 497-506.

Also, Niall Ferguson’s Ascent of Money : A Financial History of the World. S.L., Penguin Books, 2019.

[…] When ships and harpoons got better, the job got easier. Vast American fortunes (including that of Hetty Green’s family, episode 3.8) were made by hunting whales. The whales were used for many things, but the most important thing […]

LikeLike

[…] © Her Half of History […]

LikeLike

[…] ships and harpoons got better, the job got easier. Vast American fortunes (including that of Hetty Green’s family, episode 3.8) were made by hunting whales. The whales were used for many things, but the most important thing […]

LikeLike

[…] don’t mean to say that no woman or person of color could do any of that. Some could and some did (Hetty Green, Elizabeth Keckly, Maggie Lena Walker, for example). But it was more likely that a potential […]

LikeLike