So last week we looked at Hetty Green, Queen of Wall Street. I happen to really like Hetty. She was a woman who knew what she wanted and then she went out and got it. But it is nonetheless true that she was born with a silver spoon in her mouth. She was an entrenched member of the 1% who spent her life making sure that her family moved up to the 0.001%. Good for her, I say. Way to accomplish your goals, girl, but there is no doubt that being born to a wealthy family was a serious help to her, despite their deficiencies in the loving care and nurture area.

Today’s subject is someone who was not born with a silver spoon and was not taught shrewd business dealing by her father. Her total assets never compared to Hetty Green’s, but then again, being the richest woman in America was never her goal.

Maggie Lena Walker was born in 1864, the daughter of Elizabeth Draper, a kitchen servant in Richmond, Virginia. I originally assumed that servant was a euphemism for slave. Since Virginia was in the Confederacy, it simply didn’t matter that Lincoln had signed the Emancipation Proclamation 18 months earlier. However, I was wrong. Elizabeth Draper was a free black working for a white woman named Elizabeth Van Lew. Van Lew was a wealth, social elite, but she was also an abolitionist, a Union sympathizer, and a spy. I’m telling you, this woman is cool. She passed information to Union prisoners using a custard dish with a secret compartment, wrote messages in invisible ink, and dug up hidden bodies to return them to their families. Seriously, I don’t know why I haven’t seen a highly fictionalized Hollywood account of her story yet, but she will definitely get an upcoming episode in some future series on women as spies. But not today. Today the point is that she and her family had freed many (maybe all) of their slaves already, and Elizabeth Draper was working for them when she gave birth to a daughter.

So, daughter of Elizabeth Draper. At least one website leaves it discreetly at that, as if she only had a mother and no one else was involved in the process. But it will come as no surprise that in fact someone else was involved, and that someone else was Eccles Max Cuthbert, an Irish immigrant, who had joined the Confederate army and was or would soon become a newspaper correspondent. All this gets extremely confusing because some sources say that Walker wasn’t born until 1867, by which point Draper had married a black man named William Mitchell. Little Maggie did indeed grow up with the surname of Mitchell, and at least one source suggests that she perpetuated this myth herself, partly to pretend she was born within wedlock and partly to bolster her credentials as a black woman, emphasizing two black parents.

But most of my sources agree she was actually born in 1864, out of wedlock to a white father. And of course it was out of wedlock, because it would have been illegal for Draper and Cuthbert to marry, even assuming that they wanted to, and I have not found any indication that they did.

William Mitchell fulfilled the father role, as I said, but sadly, he would not survive long. He was murdered in 1876, and Elizabeth Draper Mitchell supported Maggie and her other children by taking in laundry. This is a very long way away from Hetty Green’s upbringing.

Maggie graduated from the school for colored children in 1883 and got a job teaching middle school. After three years, she married Armstead Walker and became Maggie Lena Walker, as she is known to us. Along the way she had joined the Independent Order of St. Luke’s, and now I’m going to pause her story a moment to give you a feel for the way life was for the working poor in the 19th century.

There is no Social Security, no Medicaid, no Medicare, no public health option, no medical insurance, no disability insurance, no family and medical leave, no unemployment payment, no guaranteed basic income, no food stamps. Emergency rooms barely exist, and they certainly do not have to treat you if you cannot pay. Employers and shopkeepers and bankers are allowed to discriminate on pretty much whatever basis they want. I could go on, but the point is that you are always one stroke of bad luck away from total disaster. One single accident could tip you from comfortable to indigent. You might get help from extended family, a church, a charity, or a poorhouse, but the fact remained that it was a difficult world, and getting back on your feet might well prove to be impossible.

It was not necessarily considered the government’s job to fix this, but it was recognized as a problem. Unions were picking themselves up and testing their power, but other organizations were not so much focused on a particular employer as they were on banding together to help each other through hard times. So when you joined, you’d pay in a certain monthly amount. And that money would be used to help those members who were currently struggling. Remember we’re talking about the working poor here, so that monthly payment was probably a serious sacrifice, but you’d do it because you could see all around you just how quickly you might slip from one who could work to one who could not. So it is much like modern insurance, except that the organization was also intended to be a community. These people would know each other, meet together, and support each other personally. It’s not just a financial transaction.

The exact details depended on the organization of course. St. Luke’s was focused on providing health care and burial for African Americans, many of whom had only recently stopped being slaves. Originally, it was limited to women, but had expanded to men by the 1880s. Once in, Walker rose quickly through the ranks, delegate, national deputy, committee member, Grand Secretary, and Right Worthy Grand Chief, which is a title I kind of like (Suggs). Much more impressive than a mere “president.”

Maggie Lena Walker in 1913

Image: The Browns, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

St. Luke’s was not doing so well by this point. They were 30 years old, but practically at death’s door. In 1899, they had 57 councils, but only $31.61 in the treasury. The bills amounted to $400. This was unacceptable, and with Walker at the helm, a year later they had twice as many members and the treasury was sitting pretty at $1,288.98 with no outstanding bills (Suggs).

The amount may have been all in a half hour’s work to Hetty Green, but then again, she never started so low. And all her efforts were aimed at enriching her own pockets, not a mutual benefit society.

Walker had no shortage of ambitious plans for St. Luke’s. In 1901 she laid out the goals: a bank, a store, a newspaper, and a factory. The bank was extremely important. She had realized that banks do not simply store wealth: they create it. Loans help a community grow and improve, but many white bankers did not believe that black borrowers would repay their loans, so they either would not lend, or they lent with higher interest rates. Some banks wouldn’t even accept deposits from black account holders. It’s sort of boggling to wonder what would motivate a business to turn down money being handed to them, but the rationale was that seeing black people in the bank would make white people not want to be there, and it was no secret which race would be handing over more money. And the truly sad part of all this is that those white bank owners were probably correct. There almost certainly were some white account holders who would not patronize the bank if they saw black customers there.

The result was that the African American community often could not earn interest. They could not get loans to begin businesses that would bring money into their communities. They could not borrow to tide them over during lean times. To the extent that they were able to persuade whites to give them loans, they paid higher interest rates. “The Negro” Walker declared “. . . carries to their [white people’s] bank every dollar he can get his hands upon and then goes back the next day, borrows, and then pays the white man to lend him his own money” (Brown, 623).

What they needed, Walker thought, was their own bank. “”First we need a savings bank,” she said. “Let us put our moneys together; let us use our moneys; let us put our money out at usury among ourselves, and reap the benefit ourselves. Let us have a bank that will take the nickels and turn them into dollars.”

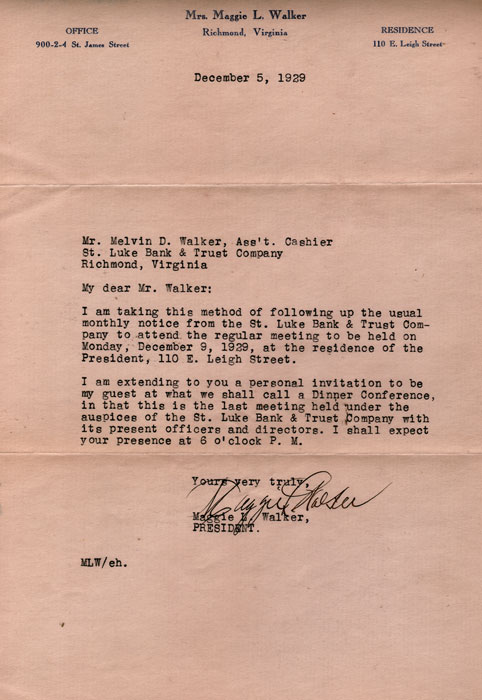

Walker was nothing if not professional. This formal letter was written to her son, inviting him to dinner in the house he lived in.

Image from the National Park Service.

It took two years to bring that bank from idea to opening day. In 1903, the charter was approved by the government, and Walker became the first African American woman to be bank president. She was pretty close to being the first American woman of any color to be bank president, this being a very, very male dominated profession. But she is beaten out in the race to first by a handful of white women, such as Louise M. Weiser, whose husband was president of a bank in Iowa until his death in 1875. She took over for him afterwards. The widow Deborah Powers of Troy, NY, started a bank while simultaneously running her husband’s successful oil cloth manufacturing business. Her bank was called D. Powers and Sons, which most people would assume was a father and sons outfit, but was not. D was her initial. Her late husband’s name was William. Evelyn Tome inherited the position of bank president in Maryland in 1898. She was also elected president of another bank and held both positions concurrently. There are a few others like these women. But what makes Maggie Lena Walker stand out is that she was no heiress. She wasn’t a wealthy widow. She didn’t have a degree in business. And she wasn’t in it because she wanted to make a profit. She was in it because she saw a need for banking in her community and wanted to do something about it.

Walker knew that she didn’t have a clue how a bank actually operates, which is a serious handicap for a bank president. A business college, which may or may not have given her the right information, was not the solution. Instead she gave herself a sort of apprenticeship. She spent two hours a day in one of the white-owned banks, observing their work. The Virginia Banker’s Association gave her membership, which they had not done for any of the other black-owned banks.

On November 2, 1903, the new bank opened its doors. 280 customers lined up to open their bank accounts, making deposits that ranged from over $100 to the very smallest of 31 cents. The total deposits on day one was just over $8000, and they also sold $1,247.00. This is incredibly small potatoes for a bank, even at that time. But it was their bank, and they were taking control.

Walker knew she needed more depositors. But more importantly, she needed to teach her community that they could save and how to do it. St. Luke families were given little piggy banks for pennies. Children were told that if they could collect 100 pennies in their bank, they could open an account at the bank. This was both for their sake (teach them while they’re young), but also for the bank’s sake. They needed more customers.

It must have required more than a little trust for adults to deposit their money here. Would you want to entrust your money to a brand new bank, run by people who had never done it before? 19th century America had been rife with bank failures. Economic ruin was a very real possibility. The government was only gradually coming to the realization that regulating banks might be a good idea. In 1910, the St. Luke’s bank was still going strong when the Virginia General Assembly decided all banks must pass a regular examination. Many banks were shut down for unsecured loans, lazy procedures, and fraud. When a bank shut down, the depositors could be pretty sure they would lose all their money. The FDIC wouldn’t be formed until the 1930s, and the government was not going to bail anyone out. Walker may have said that they’d turn nickels into dollars, but the fact was that she might well have turned nickels into thin air.

There was also the question of the gender of the person running it. A woman? Those other female bank presidents were not famous, and most of them didn’t stay bank president long. Besides, why wasn’t she at home caring for her children? Walker was practical about these complaints, rather than modern feminist: She declared that “every dollar a woman makes, some man gets the direct benefit of same. Every woman was by Divine Providence created for some man; not for some man to marry, take home and support, but for the purpose of using her powers, ability, health and strength, to forward the financial . . . success of the partnership into which she may go, if she will . . . What stronger combination could ever God make–than the partnership of a business man and a business woman.” Countering complaints about women working at all, she said, “The bold fact remains that there are more women in the world than men; . . . If each and every woman in the land was allotted a man to marry her, work for her, support her, and keep her at home, there would still be an army of women left uncared for, unprovided for, and who would be compelled to fight life’s battles alone, and without the companionship of man. . . The old doctrine that a man marries a woman to support her is pretty nearly thread-bare to-day.” Many married women worked, she said, “not for name, not for glory and honor–but for bread and for their babies” (Brown).

These women, whether married or single, were a huge part of the target audience for the Penny Bank, which was named to emphasize small donors. Many of the early depositors were washerwomen, just like Walker’s own mother (Brown).

To the surprise of many, the Penny Bank survived. By 1920, the bank had given over 600 mortgages to black families, families who almost certainly would not have been able to own homes by way of a white-owned bank.

As if running a bank wasn’t enough, Walker and St. Luke’s were busy on other fronts too. They were prominent in the 1904 streetcar boycott, when Richmond streetcars, which had been integrated, were suddenly segregated. Walker and other leaders like her, told their people to walk rather than put up with that (Meier). Walker promoted educational opportunities for black children and spoke out against lynching. She campaigned for women’s suffrage and after the 19th amendment finally passed, she led a massive push to get black women registered to vote. If you want proof of Walker’s success on that front, just look at the list of Richmond’s eligible black voters in 1920: a full 80% of them were women (Brown, 623). During the 1918 flu pandemic, she volunteered with the Red Cross and convinced the governor to convert a school into an overflow hospital with black doctors and black nurses. I’m telling you, this is a woman who knows how to get things done, and it’s not as if she didn’t have troubles of her own. In 1915, her husband had died, which sounds bad enough in a passive sort of way. But it was made infinitely worse by the manner of his death. Their oldest son Russell had mistaken him for a burglar and shot him. Russell stood trial for murder. He was eventually found not guilty, as it seemed clear to many (including Maggie) that it was accidental, but of course a great many insinuations and outright accusations had to be suffered through before they got to that point, and Russell himself would never really get over the incident. He died himself in 1923 at the age of 32.

This picture was taken about 1925. The bank was in full swing.

Image from the National Park Service.

Meanwhile, the work of the bank continued on. It was struggling but still breathing in 1928 when Walker met with two other black-owned banks in Richmond to discuss merging. It was about to be a bad time for banking, what with the Great Depression knocking on the door. Black Tuesday had already brought Wall Street to its knees before the merger went through. The new Consolidated Bank and Trust now resided in what had been the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank, and Walker was Chairman to the Board of Directors. The newly merged bank made it through the Depression and out the other side. It continued to exist until 2005, when it was bought out. But until then Maggie Lena Walker’s bank was the oldest continuously black owned bank in the country. Even today, there is still a bank on that exact location: 1st and Marshall Street in Richmond.

Maggie Lena Walker died in 1934 after spending 6 years in a wheelchair, which did not prevent her from running her bank.

She is memorialized in the Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site, which exists in the home that she lived in for 30 years, including almost all of her time as bank president. Last I checked, their website says that they have not yet resumed tours after Covid, but there is a virtual tour, which is better for those of us who don’t live nearby anyway. I’ll post a link on the website. My favorite sentence in it is the one that shows the laundry room where a woman named Polly Payne would have labored for the family. The virtual tour says: “Remembering her mother’s struggles as a washerwoman, Walker insisted on comfortable and modern conveniences for Polly including indoor plumbing, fans, and an electric press.” I knew I liked this woman. I also like that the electric press is no longer the cutting edge of laundry technology.

Selected Sources and Images

My major source for this episode is the National Park Service, who have a fabulous site about Walker, that is well worth exploring. The virtual tour of her home is here, and the Richmond News reported on her memorial and her son’s trial.

I also used the following articles:

- Brown, Elsa Barkley. “Womanist Consciousness: Maggie Lena Walker and the Independent Order of Saint Luke.” Signs 14, no. 3 (1989): 610-33. Accessed June 18, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3174404.

- Meier, August, and Elliott Rudwick. “Negro Boycotts of Segregated Streetcars in Virginia, 1904-1907.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 81, no. 4 (1973): 479-87. Accessed July 1, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4247829.

- Suggs, Celia Jackson, and Maggie L. Walker. “Maggie Lena Walker.” Negro History Bulletin 63, no. 1/4 (2000): 39-44. Accessed June 16, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44985764.

[…] of such a thing. But one of these probably free African-Americans was Elizabeth Draper, mother of Maggie Lena Walker, a powerhouse of a woman who I discussed in episode 3.9. Maggie was born in the Van Lew […]

LikeLike

[…] or person of color could do any of that. Some could and some did (Hetty Green, Elizabeth Keckly, Maggie Lena Walker, for example). But it was more likely that a potential investor would turn them down because they […]

LikeLike