To anyone whose concept of slavery stems from the African-American experience, Roxelana’s life is mind blowing. There are pieces of it which are oh-so-familiar and then the rest of it sounds like it belongs in a different series altogether. That’s because Ottoman slavery as an institution looked very different from our normal mental image. And also because Roxelana is such an outlier just in and of herself. But she was a slave, and she did become free (to say the least). So she does belong in this series and this is her story:

Like most slaves, we’ve got only a hazy idea of her birth. After the triumph of her adult years, many countries have attempted to claim her as their own national hero, but most of those back stories are obviously fictional. The oldest and most believable claims are that she was born in Ruthenia, which was a large area which currently falls in the western Ukraine, but at the time was under the control of the Polish king. The year would have been somewhere in the first decade of the 1500s. Her parents’ names, professions, and status are unknown. Her original name is also unknown. It certainly was not Roxelana.

The exact story of her captivity is also unknown, but we can guess. Slavery was no new thing on the Eurasian steppe, but the major perpetrators at Roxelana’s time were the Tatars from Crimea. As we discussed in episode 4.1, Muslims were theoretically not supposed to enslave other Muslims, but that didn’t mean there wasn’t demand for slaves. The Tatars supplied that demand by raiding north and west into Christian lands. They preferred coming in wintertime, when rivers were frozen over and aided their movements. And they moved fast. They burned or destroyed what they could not take with them. Prisoners were chained and forced to walk. They were given little food. Sometimes relatives could pay ransoms at extortionary rates to free them, but many died in the journey. A Polish proverb said “O how much better to lie on one’s bier, than to be a captive on the way to Tartary” (Peirce, 22). We do not know whether Roxelana’s family was chained up with her, or whether they lay dead, or whether they simply did not have the money or the desire to ransom her.

Christian Europe was appalled by all this, which was plenty hypocritical since they had slaves themselves. But still, they were appalled, enough so that the word for slave in many European languages stems from Slav, the ethnicity of the people who bore the brunt of raiding.

Roxelana must have survived the journey to Caffa, where most of the slaves were taken. There her captors would have paid taxes on her. (In 1520, the slave tax was the single largest item in the Ottoman empire’s budget, if that gives you a sense of the scale of this operation.) After that, she may have been purchased directly by Imperial agents looking for palace servants. Or she might have been sent up on the auction block. Either way she would have been examined from hair to toe, including a check for virginity, before the price was settled. She was probably no more than 15 years old.

The Sultan’s Harim

One way or another, Roxelana must have ended up in the Old Palace in Istanbul. Now let’s pause for a moment to explain the way the Ottoman court worked because it’s substantially different than the western courts you may be more familiar with. In the Ottoman Empire there is no such office as Queen. Nope, the sultan instead has many, many concubines, and all of their sons are potentially eligible to inherit the throne regardless of birth order. The sultan would choose from among the many women in his harem, and if she pleased him, he would keep her around long enough to have a child, hopefully a boy. Once she gave birth to a son, her world changed. She got a huge rise in status, and she was also 100% ineligible for any further physical relationship with the sultan. The rationale was that from then on, her job was simply to educate and promote her son. Another child would only divide her attention from that prince, to the detriment of all. The sultan chose another concubine and started the process over.

Naturally there would be a good deal of infighting between princes and their mothers, so it was common to send a teenage prince and his mother out to one of the provinces for hands on experience and also so that they wouldn’t kill each other too early. Killing each other later was pretty much expected. That’s how they ensured that the sultan was a strong leader. If he wasn’t, he was undoubtedly cut down by a half-brother who was.

In the early days of the Empire, the concubines may have been foreign princesses brought into create alliances, just like Western Europeans did it. But that didn’t work well for long because foreign princesses tended to object to being sent out to distant provinces with their sons and they might have foreign loyalties that impeded their ability to work single-mindedly for the benefit of their son. So from about 1400 on, the concubines were not foreign princesses, they were foreign slaves. Slaves who could be retrained to have no loyalties other than to the Ottoman Empire (Peirce, 20).

What all this means is that although Roxelana is a slave, and she was ripped from her home and family, and she undoubtedly suffered both mentally and physically on her way to Istanbul, her status once there was quite different from what millions of other slaves have experienced. She must have worked hard, yes, but not in the fields or the mines. No, she would have been set to learning Turkish, converting to Islam, mastering court etiquette, politics, etc. Everyone would have known that she was a potential mother to a sultan, and she had to know enough to guide him well.

Of course, many potential concubines never made it so far. If she failed to catch the sultan’s eye, or if she displeased him, or if she didn’t bear a son, she would find herself demoted to menial labor in the slave palace. Or possibly sold away. So she had every incentive to work hard, to convert, to learn. In the modern world it is hard to imagine how you could be loyal to a regime that had purchased you as a slave and tacitly consented to your capture in the first place, but what did these slaves have to return to? Their homes were destroyed, their families scattered. They were being offered a life far more luxurious than anything they could have dreamed of at home. Most of them wouldn’t have expected a love marriage even if life had gone as planned. As repulsive as it is, the Ottoman system worked rather well. The slaves were reasonably loyal. The sultans were talented and strong.

This painting is by Titian, and although it was done during her lifetime, it is highly unlikely that Titian ever saw her. All he had to go on was reports from ambassadors and travelers from the Empire.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Favored Concubine

We do not know the details, but the young sultan Suleyman chose Roxelana, shortly after his ascension to the throne. She must have left the Old Palace (the province of women guarded by eunuchs) and come to the New Palace (the province of men). In the fall of 1521, Roxelana gave birth to a son, named Mehmed.

Suleyman had four other children already by other concubines. But shortly after Mehmed’s birth, three of them died unexpectedly. Mehmed was now the second son. And child mortality rates like that were exactly why it was now important for Suleyman to father other children. He needed not just an heir and a spare, but an heir and multiple spares. It was time to set Roxelana aside and pick someone else.

There would be compensations for her. Royal mothers were given a big boost in salary. As a slave, you might wonder that they are given any salary at all but remember these aren’t slaves toiling away in the field. These slaves are expected to be pretty, clean, well-dressed, etc. That takes money. In addition to substantially more money, she got private quarters. Other lower-status women in the Old Palace would serve her and the baby. She would also be expected to entertain. Especially if Suleyman came to see his child and the child’s mother. Also, and this is important to us, a royal mother could no longer be sold away. She was there in the family permanently. If you remember episode 4.1, we talked about how slavery is marked by having no right to family. By that definition, Roxelana is no longer a slave. She has freed herself by having a son. And indeed one European chronicler said exactly that. But under the Ottoman law, she was still called a slave until the death of her master. On Suleyman’s death she would be free, and not before (Peirce, 54). So it depends on your definitions, but certainly her status had improved, even if her career as a concubine was now over.

Except that Suleyman defied all tradition and did not sever their relationship. Within months, Roxelana was pregnant again, a thing that was not supposed to happen. Over the next few years, Roxelana presented Suleyman with a total of four boys and one daughter. And interestingly, no other concubine gave birth for the rest of Suleyman’s reign. The Ottoman emperor was apparently monogamous. The empire and the foreign observers were utterly flummoxed.

Roxelana was, of course, accused of sorcery, witchcraft, and all sorts of other deeds, while the world asked the age-old question: “What does he see in her?” In addition, there was some concern for the young princes. How could they possibly compete against Mustafa, the oldest prince, who had his mother’s sole attention, when their mother must divide her guidance between them? This was not a beautiful love story to them. It was a potentially dynastic disaster for the Empire.

We don’t know exactly what Suleyman was thinking. Perhaps he just loved her. Or perhaps his decision was more calculated. The Ottoman system had spared the Empire from the kind of protracted civil war over the throne demonstrated by, say the English with their Wars of the Roses. But it didn’t save the family from violence as princes battled each other. His father had achieved the throne by means of multiple fratricides. Suleyman himself had been luckier: none of his brothers had survived to adulthood. Whether that was a natural occurrence or not is disputed, but it appears to be Suleyman’s father, not Suleyman, who disposed of the brothers, if there were any to be disposed of (Peirce, 64). Perhaps Suleyman did not want to perpetuate this system. Perhaps his own mother, a former slave concubine herself and now the first ranking female in the Empire, helped him decide. She had probably come from a Christian monogamous society, though like most slave concubines, her origins have been obscured. Whatever the reasons, there it was. Roxelana was a permanent fixture in the New Palace.

Not a Concubine, but a Wife

Suleyman was not done flouting tradition. His mother died in 1534. In a culture without reigning queens, the mother of the sultan was the First Woman of the empire. She had undoubtedly had a big role to play in Roxelana’s training and rise, though we don’t have any details. Within two months of her passing, Suleyman married his favorite concubine. He married her. This just wasn’t done. The sultan never married. It was in fact problematic for him to marry in multiple ways. For one thing, he was supposed to have a string of concubines to secure the dynasty. For another thing, by law he must have freed her first: you couldn’t marry a slave (Peirce, 115). And for another thing, he had created a status for her which no one, including Roxelana herself, knew how to handle.

How much of this emancipation + marriage was Roxelana’s idea, we don’t know. The Hapsburg ambassador said it was all her, saying that “she refused to have anything more to do with Soleiman, who was deeply in love with her, unless he made her his lawful wife (Peirce, 119)” How exactly Roxelana was supposed to refuse, given her lack of options, isn’t totally clear to me, so maybe this is just part of the scheming, manipulative woman narrative. But we don’t really know. Ottoman sources are, as usual, silent.

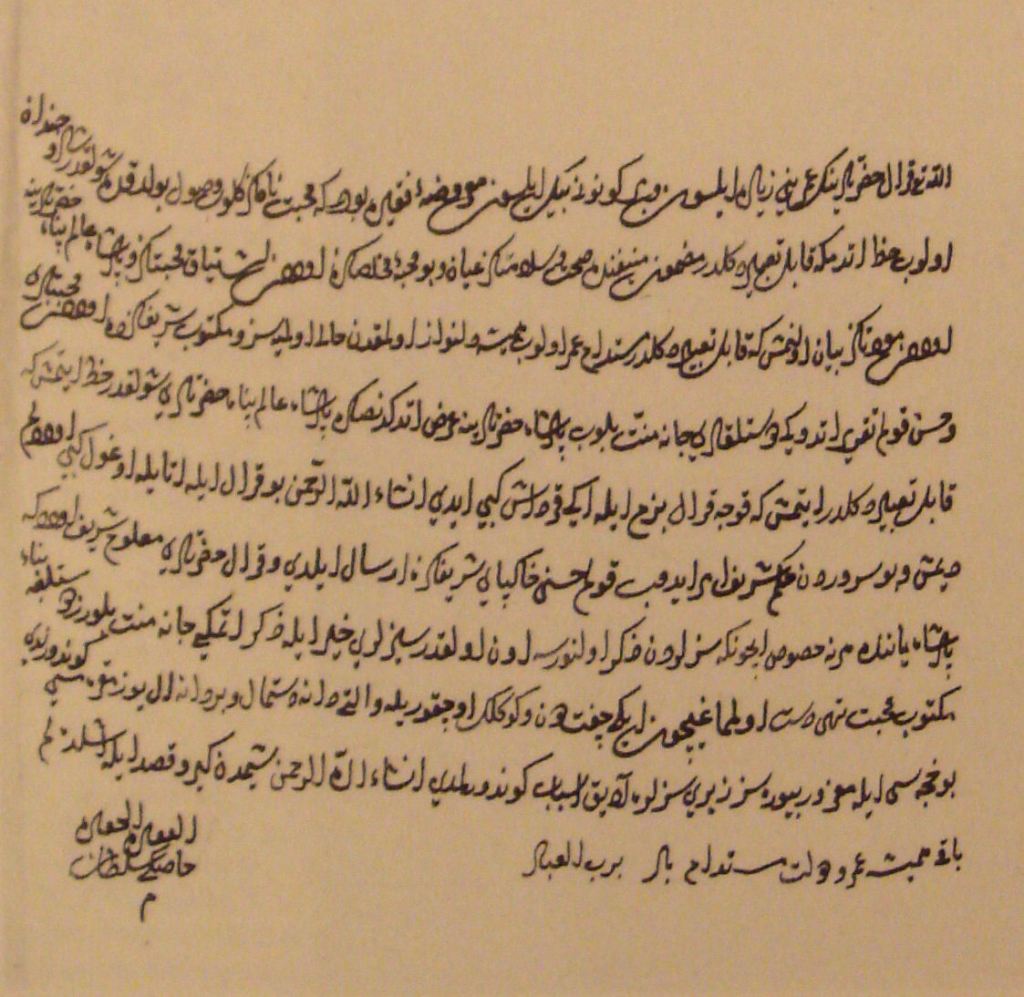

Up to this point, we have been reliant primarily on European ambassadors reports about Roxelana and how the slavery worked. This is obviously not the source we would prefer, but now, we start to get some words from Roxelana herself. Suleyman was frequently away on military campaigns, sometimes for more than a year at a time. Roxelana wrote to him, and some of her letters have survived. Her letters were lengthy and somewhat difficult to follow, but let’s make allowances when you remember that Turkish is not her native language, and we have also lost some of the letters so the thread of the conversation has holes. Chiefly, however, she writes about missing Suleyman. For example, she writes to him that “day and night I burn in the fire of grief over separation from you (Peirce, 142)”, that she is drowning in the sea of longing, no longer able to tell day from night (Peirce, 209), and that she is capable of nothing but suffering in his absence (Peirce, 282).

If you, like me, are feeling ever so slightly sick to your stomach, please do remember that expressions of love are very culture-dependent. You can also take a line like “What light through yonder window breaks? It is the east and Juliet is the sun” and feel either thrilled or nauseated, depending on how you approach it.

We can also get a sense of other things about Roxelana through the letters. She is a perfectionist. She wants her surroundings to be just right. She has trouble reigning in her expenses. She is a devoted mother, concerned especially about her youngest son whose shoulder had not developed correctly.

One of Roxelana’s surviving letters. This one is not of the over-the-top love professions to Suleiman because it is to Sigismund, offering congratulations on ascending to the Polish throne.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

She was known to the Ottomans as Hurrem, which means joyful or laughing (Peirce, 4), and that does seem to be an accurate depiction of her character as seen by her family. But she was also known to her subjects as Ziadi, which means witch (Peirce, 147). Because what other explanation for her hold over the sultan could there be?

Defining the Role of Queen

The role of queen was a new one to the Ottomans and Roxelana set about defining it. Muslims were big on charitable giving, but typically the royal mothers sponsored a public project only after their sons moved on to govern a province, and the project was done in that province. Roxelana had no intention of waiting. She sponsored the first foundation in Istanbul to be donated by and named after a woman. Even today, that area of Istanbul is known as Haseki (meaning the royal favorite) (Peirce, 171). In Roxelana’s time, the area was known as the Avrat Pazar, meaning the women’s market. In it, she built a mosque, a primary school, a college, a soup kitchen, and a hospital. In the charter, Roxelana specified how all this was to be run and by whom and with what qualifications. Of special note is that one of the key administrators was required to be a female scribe, rather unusual for the time. Also that the school teacher must be kind and compassionate to the children, which is also seen as Roxelana’s addition to the usual qualifications. The soup kitchen did not serve as many poor as you might be imagining. Spots were limited. But her charter included provisions for meat twice a week, plus butter, saffron, honey, nuts, fruits, and other luxuries. It was more than just your bare minimum.

The Haseki complex in Istanbul, built by Roxelana.

Roxelana was also now the head of the Old Palace, since her mother-in-law had died. This included both day-to-day administration but also important duties like finding appropriate husbands for all the girls who had finished their training, but not been chosen as concubines. In 1541, the Old Palace burned to the ground. The women fled into the public square, which for many of them would have been the first time they had seen or been seen by the outside world. Roxelana lost a million gold pieces, plus jewels and other items, but she and her children were not in the Old Palace at the time. They were safe.

Those children were growing up though. By tradition, an up-and-coming prince and his mother were sent to govern a distant province as practice. This is exactly what Mustafa, the oldest prince and his mother were doing. But obviously Roxelana could not accompany multiple princes to multiple provinces. So when her oldest Mehmed became governor of Manisa at age 21, he was older than most Ottoman princes were on arrival and he lacked the guidance of the one advisor who could be counted on to have nothing but his interests at heart: his mother. His 19-year-old brother Selim was made governor of Konya at the same time. He also did not have his mother. She stayed in Istanbul with Suleyman and the younger children. No one, least of all their parents, knew what impact this would have on their chances of succeeding.

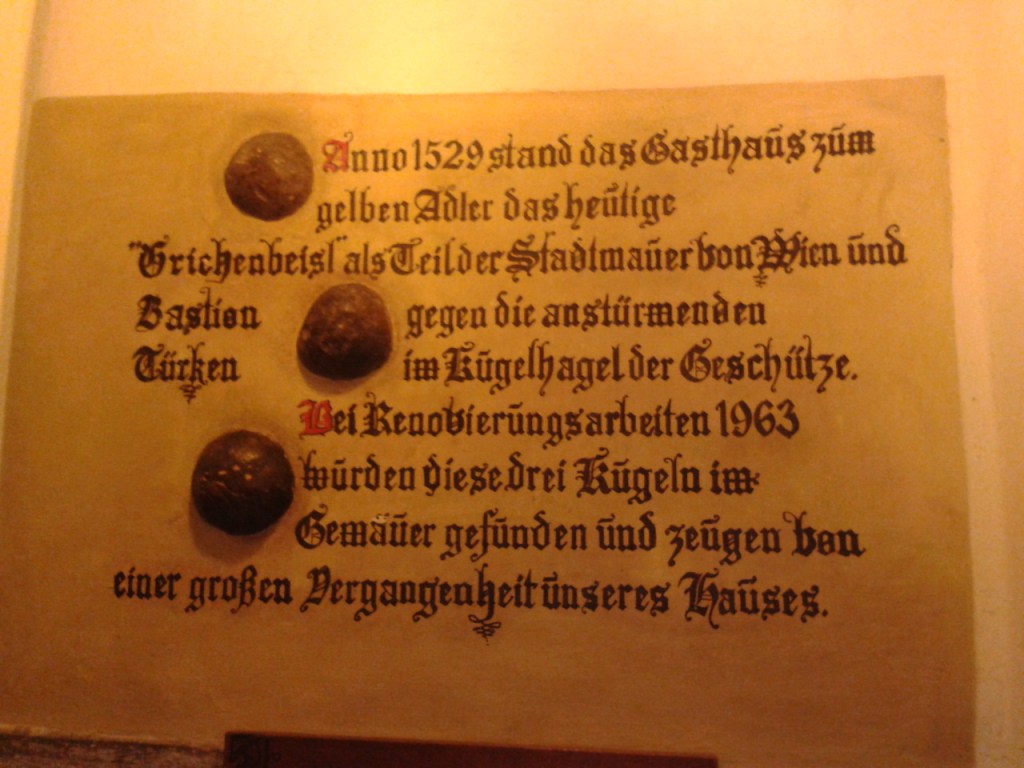

It was also about this time that Roxelana began influencing foreign politics directly, by means of correspondence with other leaders, and particularly the women, such as Isabella, the disputed queen of Hungary. Roxelana took her side against the Hapsburgs. Later she corresponded with the Polish monarchs and the Safavid royal women. Meanwhile, Suleyman was still pursuing his wars in the area and mostly succeeding. This is Suleyman the Great we are talking about. He campaigned against Europe and got as far as threatening Vienna. To this day, there’s a restaurant in Vienna where you can still see the Turkish cannonball in the wall. I’ve eaten there, and I was rather embarrassed at how far into my research for this episode I was before I realized I was reading about the original owner of that cannonball.

But the news of victory from the front was followed up by terrible news. Mehmed, Roxelana’s oldest son, suddenly died after 6 days of illness. He had governed Manisa for only one year.

The Coming of Grief

Suleyman’s grief is well recorded: hours of weeping, days of refusing to bury his son, over ten times the ordinary number of days of prayers for the dead. The sources are silent about Roxelana’s grief, but that does not mean it was any less. We know only that she was the driver behind the memorial mosque that was built in Mehmed’s honor. She is even said to have sold her gold and jewels because she noticed that the janissaries who built the mosque had inadequate shoes and she wanted to provide them with a raise.

Roxelana could afford to be generous. Her daily stipend was 2,000 silver aspers per day, which conveys pretty much nothing to my mind, but is more revealing when you know that Suleyman’s sisters, who were the next highest ranking women received 200 silver aspers per day. The ordinary concubine mothers might receive only 30 aspers per day. The income allowed Roxelana to both live lavishly, send gifts to foreign monarchs, and pursue yet more building projects, including a hostel for pilgrims in both Mecca and Medina.

Yet all was not well on the home front. Suleyman was growing older, he was sometimes gone to the wars, and there was still no clear successor. Mehmed was dead, but Mustafa, his first-born with another concubine was popular with the soldiers. It was not at all clear whether Suleyman who had broken with tradition in the matter of his wife intended to break with tradition in the matter of succession either. Would he promote one son? Or would he and Roxelana stand by while their sons fought first Mustafa and then each other?

A partial answer was soon clear. Reports came that the army was restless, that they thought Suleyman was old and weak, that they thought Mustafa should seize the throne for himself, even while his father was still alive. Suleyman felt threatened. He summoned Mustafa to meet him (nothing unusual in that). Many people advised Mustafa not to go, including his mother. But he went anyway. And on Suleyman’s command, he was strangled.

Mustafa was instantly a martyr. We cannot know for certain whether he was guilty of treasonous thoughts. If he was planning a coup, he certainly had not gotten very far. The grand vizier was accused of plotting against him and poisoning Suleyman’s mind against his son. Roxelana was accused of the same thing. She was a scheming witch, they said, determined to make sure that one of her sons reached the throne.

There is no actual evidence, however. It’s just an assumption, since she and her remaining sons were the obvious ones to benefit from Mustafa’s death. And perhaps it’s true. But a clearer mind can also assume that Suleyman was no fool: he had ruled competently and well for decades now. Whatever Roxelana may or may not have said to him, ultimately he made the decision and he gave the command.

Either way, it was now quite clear that one of Roxelana’s sons would be the next sultan: no one else was left. In another sense, that was hardly comforting. According to tradition, Roxelana would have the privilege of watching her own flesh and blood kill each other, and she still had 3 living sons. Many commentators then and since tried to work out whether she had a favorite or whether Suleyman had a favorite. Neither ever formally declared which they preferred. But their youngest would not last long: Cihangir died of a sudden sickness. He was buried next to his older brother in Istanbul, and to this day there is a neighborhood named in his honor.

In her last years, Roxelana’s letters to Suleyman retain their fawning flattery, but her Turkish is better and her sense of the politics is stronger. She conveys to him the instability in the mood at court, urges him to reinstate an exiled grand vizier, placates his suspicions over the behavior of their remaining sons, and worries increasingly over his declining health.

As it happens, her own health was the one that would give out first. After a lingering illness, she died on April 15, 1558, within the walls of the Old Palace, where she had been brought as a slave so many years before. One traveler wrote, “The sultan loved her to distraction and his heart has broken with her death” (Peirce, 303).

I would like to end this here, but unfortunately that leaves a few loose threads, and they aren’t pleasant ones. Perhaps Roxelana preferred dying relatively young because at least she did not live to see her husband and her sons destroy each other over the throne. It seems that they had been waiting only out of respect for her. Within months of her death, Bayezid began raising an army. He lost the battle and fled to Iran. Suleyman ransomed him and then executed him as a rebel. Eight years later, when Suleyman himself died, Selim, the only remaining son, would inherit the empire.

Selected Sources

My major source for this episode was Empress of the East: How a Slave Girl Became Queen of the Ottoman Empire by Leslie Pierce.

[…] I have unearthed a handful of other slave women to talk about. We’ll visit Greece, the Ottoman Empire, Spain, and Brazil before we end up in the USA for the larger share of the […]

LikeLike

[…] some girls. If you were a slave girl in the Ottoman Empire, you might get an education (see episode 4.3 on Roxelana). But for many owners, it was not only a waste of time to educate slave children, it was actually […]

LikeLike

[…] there is a title given to women of high status. Longtime listeners of this show may remember Roxelana, the Ottoman queen, episode 4.3? She was also called […]

LikeLike

[…] than a short life of unrelenting hard labor. The most stunning example of this that I know of is Roxelana, episode 4.3, from slave girl to empress. But it never would have worked if she hadn’t been […]

LikeLike

[…] things start to get wild from a feminist point of view. On this podcast we’ve seen women who were sold into marriage. We’ve seen many women who were told who to marry. We’ve seen women who married against their […]

LikeLike