If you imagine a slave running for freedom, you probably have a certain mental image in your head. You’re probably thinking about sneaking through the woods at night, cold, wet, and hungry, heart thumping, ears ever strained for the sound of men or dogs in pursuit.

That’s exactly what it was like for many, and we’ll hear some of those stories like that next week when we get to Harriet Tubman. But there was one woman who managed her escape in an entirely different way. Her heart thumped, I am sure. But otherwise, there is no comparison. She had one significant advantage over most of her fellow runaways, though, and this is her story:

Ellen was born in Georgia, which in and of itself is a reason to wonder at her escape. Most successful runaways were those who, like Harriet Tubman, had the good fortune to live near a free state. Selling a slave south was an effective threat in part because it was so much farther from freedom.

Georgia was south. And in Ellen’s early life there did not seem to be much hope that she would ever be free. She was owned by her father, a white man. Her mother was, of course, his slave. Her mother must have had one white parent as well, because Ellen was what they called a quadroon: meaning someone of ¼ African descent and Ellen was very fair-skinned. She was so fair- skinned that she was often mistaken for one of the legitimate members of the family, much to the irritation of the lady of the house. But having more European than African ancestors made no difference to her real status. Any African blood was enough. She was a slave, however much she might look like an owner.

When Ellen was eleven, her mistress got tired of the frequent confusion. To get rid of her, she gave Ellen to her own daughter as a wedding present. This meant separation from her mother and the only home she had known, but at least she was away from that mistress who was so angry over her skin color.

As she grew older she met a fellow slave named William Craft. Craft was fortunate to be highly trained and skilled as a cabinet maker, and he wanted to marry her, but Ellen did not want to be married. She had seen what happened to slave families, and so had William. As a slave, you could never ever be sure that your family would not be torn apart at a moment’s notice. She didn’t want that.

They discussed escape, but it didn’t seem possible. Macon, Georgia, was over 1,000 miles from the land of the free, and 1,000 miles of hostile territory was just too much. They would never make it.

Reluctantly, Ellen agreed to marry William because liberty was not a possibility.

Until December of 1848, when William thought of a plan. The plan hinged on the fact that Ellen was so frequently mistaken for a white woman. What if, he said, they purchased her new clothes? She would travel as a free, white slave owner. And he would travel as her dutiful slave?

Already this sounds nerve-wracking, but it gets worse. It would not be normal for a white woman to travel with just a male slave. Everyone would have noticed that. So Ellen wouldn’t be going as a white woman. She’d have to go as a white man.

Can you just imagine what sensible Ellen must have thought when William proposed this crazy scheme? She was 22 years old and had probably never worn pants in her life. She had probably never left the state of Georgia. She had never owned herself, much less another human being. Her voice was too high, her body curved in all the wrong places! There were a million things that could go badly in this plan and they knew very, very well what fate awaited runaway slaves who were caught.

It took some convincing, but eventually she said, and I quote, “I think it is almost too much for us to undertake; however, I feel that God is on our side, and with his assistance… we shall be able to succeed” (Craft, 697).

The first step was to get her new clothes. And here we get to a part I wish we had better detail on. William Craft later wrote a book, which is how we know as much as we do, but he does not explain the source of his money.

As I said in episode 4.1, slaves may not have had a legal right to property, but in practice they often did anyway. Some slaves were allowed to take on side jobs and keep the cash they earned. As a cabinet-maker, William was well placed to do something like that. Ellen was a highly trained ladies’ maid, and she may have received tips or gifts of cash. Of course, theft is also a possibility, but it seems unlikely that they would have risked that. It would only make the hunt for them all the more vicious.

However they managed, William seems to have had no trouble buying any of the necessary clothes, except trousers which Ellen made herself, and as we’ll soon see this was just the beginning of their expenses. While silent about the source of the money, he is quick to point out that it was illegal for these clothing merchants to sell him anything. They did so anyway on a regular basis. Not because they liked slaves, but because they knew a slave could not testify against them in court. So who was going to know? Business is business when you know you can’t be prosecuted.

With the clothes carefully locked away, the next step was to get themselves a little breathing room. Good slave owners (if that isn’t a contradiction in terms) sometimes gave their favorite slaves a holiday at Christmas. William asked his cabinet-maker. Ellen asked her mistress. Both were granted passes to take a few days off.

All well and good, but the passes reminded Ellen of an obstacle still to be surmounted. She knew that hotels would ask her to sign her name in their register. And she didn’t know how to write, it being illegal to teach a slave such a skill. William couldn’t either.

And it was Ellen who came up with the solution. She made a sling and bound up her right arm in it. Naturally with her new injury, she couldn’t possibly sign her own name, so it was only natural that she would ask the hotel clerks to sign her name for her. She also worried that the total absence of a 5′ o ‘clock shadow would give her away, so for good measure she made a bandage for her jaw as well. William produced a pair of green spectacles to further obscure her face. And there she was: an injured, white, slave-owning man.

If the consequences of failure had not been so severe, it actually sounds like something someone might do for fun. But the consequences were so severe, and I doubt that it was any fun at all. Ellen must have had sweaty palms and a sick feeling in her stomachs as William cut her hair. There could be no changing her mind after that.

When the time came, they blew out the candles, knelt down and prayed. They rose and William peeped out the door. The coast was clear, but understandably Ellen burst into tears. But it lasted only a few moments and then she was ready.

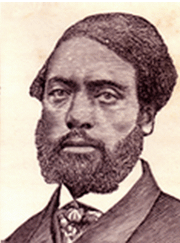

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

They slipped out the door together, but that was all the together they would get. They were afraid of being recognized, so they took different routes to the station. Ellen got there and purchased two tickets, one for a white gentleman and one for a slave. She then stepped into one of the first class cars. William, of course, got in the Negro car. They would not be able to see each other or communicate if things went wrong, and things went wrong immediately. The cabinet-maker was no fool: he suspected William was trying to run off and he was there, peering into all the carriages. He peered into Ellen’s, but he did not recognize her, and the train left before he got to William’s car.

William had been crouching in the darkest corner of his carriage, but Ellen had to find a different way of hiding. To her horror, one of her fellow passengers was a good friend of her owner’s, someone she had known since her childhood. Very politely, he said to her, “It is a very fine morning, sir.” Ellen only stared out the window. He repeated it, but only when another passenger practically shouted it, did she turn, say “Yes,” and then look back out the window. Whereupon the whole car full of men decided she was mostly deaf and they stopped trying to talk to her.

By evening they arrived in Savannah, took a horse-drawn bus to the port, and got on a steamer which would take them to Charleston, South Carolina, over night.

The steamer had a berth for Ellen and she feigned rheumatism as an excuse for going to bed early, but the steward informed William that the boat had no place for black passengers, whether they were slaves or free. So he paced the deck until late and quiet before settling himself on some bags of cotton near the funnel for what remained of the night.

At breakfast the next morning, Ellen was given pride of place and seated next to the cabin, where she listened impassively as the captain warned her against taking her “boy” up North where he was sure to run off and a fellow passenger offered to help her out of the difficulty by giving her hard silver dollars for him right now.

Ellen replied coolly that she didn’t wish to sell, she needed his help to get on, what with her injuries, but she thanked the captain for his advice. Another passenger informed her that she was spoiling her slave by saying please and thank you to him and demonstrated the thundering tone she ought to use on his own poor slave.

I have no doubt that she was very, very thankful to get to port.

But of course the danger wasn’t over. There Ellen had to buy tickets to Wilmington, NC, and pay a dollar duty on her slave. She paid the dollar but when she pointed to her hand in the poultice and

and asked the official to sign her name for her, he absolutely refused and made enough of a scene about it that he attracted the attention of everyone at the station.

Ellen must have been silently panicking, but an unlikely rescuer appeared. The very officer who had chided her for saying please and thank you to her slave stepped forward and claimed he knew “Mr. Johnson” (as she was calling herself) quite well and all his friends. The officer was well-known and liked in Charleston, so no less a person than the captain of the steamer himself came forward and signed for Mr. Johnson and slave.

Just why the officer was so helpful, the Crafts never found out, but they did learn why the signature was such an issue. The captain told them on the journey that rules were very strict in Charleston, and some slaveowners had been detained there until reliable information could be gathered on them. They had to be careful, he said, If they weren’t, any damned abolitionist might sneak off with a lot of valuable slaves.

Ellen said “I suppose so” very gravely and thanked him for his help.

From Wilmington, they took a train to Richmond, Virginia.

William found himself under questioning about his master, where he was going, what was wrong with him, etc. He was assured that the very best advice could be had in Philadelphia, (which William drily writes was quite correct, though it came from abolitionists, not physicians), On hearing the complaint was inflammatory rheumatism, his inquisitive fellow passenger insisted that Ellen lie down in the car and rest. Two young ladies politely offered their shawls for a pillow, and Ellen, glad for an excuse not to make conversation pretended to go to sleep.

On reaching Richmond, Ellen was given a recipe with a cure for rheumatism, which she took and quickly placed in her pocket for fear that she would accidentally hold it upside down while pretending to read it.

In Richmond they changed trains and while walking down the platform a Richmond lady pointed at William and said, “Bless my soul, there goes my Ned!”

Ellen quickly corrected her: “No; that is my boy.”

The lady did recognize her mistake and said she hoped William would not turn out to be as worthless as her Ned who had run away, after which she proceeded to tell everyone how she had sold Ned’s wife down to New Orleans (for her own good), but slaves never knew what was good for them, how much better off slaves were than the free blacks in the North, how 10 had run away from her, how she wished there were no blacks in the world because they were more trouble than they were worth, and how if she ever caught her runaways, she would tan their accursed hides well for them. “God forgive me “she added “but those blacks will make me lose all my religion.”

When this horrific personage finally got out at her stop, a Southern gentleman still in the car said to Ellen, “If she has religion, may the devil prevent me from ever being converted.”

Ellen and William had left home on December 21st, a Wednesday, a mere four days after William dreamed up the plan in the first place. They arrived in Baltimore on Saturday evening, which was Christmas Eve. Their anxiety was at fever pitch because they knew that Baltimore was the last major slave port before free territory.

And sure enough, an officer of the train stopped them, insisting that it was against the rules “to let any man take a slave past here, unless he can satisfy them in the office that he has a right to take him along.”

This little altercation took place in the office, with many passengers nearby, and the passengers were not best pleased. As Ellen looked like an invalid, they were irritated with the officer for being so difficult.

Ellen must have been quaking in her boots, but her voice was firm. “I bought tickets in Charleston to pass us through to Philadelphia,” she insisted, “and therefore you have no right to detain us here.”

William, of course, could only hang back feeling useless and terrified.

There were a few moments of silence, while Ellen silently prayed for help. The bell for the train rang. And all at once the officer ran his fingers through his hair,” and in a great state of agitation he said “I really don’t know what to do; I calculate it is all right.” He told the conductor to let them on, saying “As he is not well, it is a pity to stop him here.” They stepped on the train just as it was pulling away.

What they did not know was that when the train reached the Susquehanna River, all the 1st class passengers would get off the train to take the ferry across and board again on the other side. Why, I don’t know, but I find modern airlines equally baffling, so I guess not much has changed.

Ellen got off, as instructed. It was dark, cold, raining, and William was nowhere to be seen.

With rising panic, she asked the conductor if he had seen her slave. And he said, “No, Sir; I haven’t seen anything of him for some time: I have no doubt he has run away, and is in Philadelphia, free, long before now.”

Ellen dismissed this idea immediately and asked the conductor for his help in finding William, but it just was her bad luck that she had found her first abolitionist because he answered angrily that he was no slave hunter and he would do no such thing.

Ellen felt utterly desolate, sure that William had been caught by an actual slave hunter or perhaps even killed in his efforts to escape. She also knew that all of their remaining money was in his pocket, for the very good reason that any rational pickpocket would try to steal from her, not from her slave.

Finally, not knowing what else to do, she got on the ferry feeling absolutely sick and not at all the way she had expected to feel in the last moments before freedom.

What had really happened to William was much simpler than what Ellen was imagining. He was exhausted, quite understandably, and he had found a quiet corner to go to sleep in, not knowing anything about the plans for the first class passengers.

Across the river, a guard found him, gave him a shaking and informed him that his master thought he had run away and was scared half to death about him. He said, “I never saw a fellow so badly scared about losing his slave in my life.” And then he and another man proceeded to give William a lot of advice about running away, including the address of a boarding house in Philadelphia where he would be safe.

The information proved useful, though. For in the morning, Christmas morning, the train stopped at the Philadelphia station. The Crafts got off the train and Ellen said, “Thank God, William, we are safe!” and burst into tears.

William is a good Victorian man, and so does not mention any tears on his part, but I’d be surprised if Ellen was the only one crying.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

To wrap up the story, they asked at the boarding house whether it would be safe to stay in Philadelphia, and the answer was no. Philly was free, but dangerous. Slave hunters were there too. Still, they stayed for a while with a white family of abolitionists who gave them a place to stay and started teaching them to read. Soon, though they moved on to Boston. Slave hunters went there too, but it was farther from the border and had a very strong community of abolitionists to protect them. They made their living there as cabinet-maker and seamstress

In 1850, the Fugitive Slave Law was passed, which meant the Crafts’ former owners could legally claim them, even in Boston, and it would be a crime for anyone to try to stop them. Sure enough, a writ was served for the purpose of arresting them.

After a great deal of trouble on all sides, including friends who tried to help them and the president of the United States who tried to help their owners, they decided they must run again, this time beyond the reach of the Fugitive slave law. They traveled north to Canada and then on to England. There they had five children, not one of which was ever in danger of being sold away from them. They did eventually come back though. In the 1870s, when the war was over and the Emancipation Proclamation was reality, they moved to back to their native Georgia, bought a plantation, and established a school for their fellow ex-slaves. And if you know anything about Reconstruction in the Deep South, you’ll know that must have brought plenty of heart-thumping too.

One of their five children preferred to live in England, and some of his descendants still live in the Surrey area where the Crafts spent their 20 years and wrote their book. One of them has since successfully campaigned to put up signs in the village commemorating Ellen and William there, and no, when I looked at the picture, I could not possibly have identified which of the stereotypically British-looking people in the picture was the descendant of escaped slaves. Only the caption identified him.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Certainly Ellen Craft’s escape method is the most unusual and unexpected route I came across while researching this series, but perhaps it is only unusual because it would never have worked for the vast majority of slaves. We tend to think of all slaves at the bottom of the social hierarchy, but there’s a hierarchy within the slave class too, and William and Ellen were at the very top of that one: highly trained, socially experienced, possessing ready cash, and in Ellen’s case, physically more like a slave owner than a slave. If she had been an ordinary field slave, probably only the end of the war would have freed her.

Selected Sources

My major source for this episode in William Craft’s own Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom; or the Escape of William and Ellen Craft from Slavery. The entire text is here from Project Gutenberg. It was originally published under his name, but I’ll just add that more recent commentators have argued that Ellen contributed quite a bit and should have had her name on it too. It’s an easy read, though very Victorian, with frequent bursts of poetry.

If you’d rather skip the poetry, you can try the Smithsonian Magazine’s article on Ellen. Or the National Park Service’s article on her. Or the BBC’s article on the new plaque going up in England on her former home.

[…] were legally bound to assist them. Northerners like the Beechers were furious. That fall Ellen Craft, who I covered in episode 4.8, was one of several celebrated cases where slave catchers tried to do […]

LikeLike

[…] If I run through the women I covered in series 3, women who escaped slavery, you can see it. Ellen Craft, Elizabeth Keckly, and Harriet Tubman were married. Elizabeth Freeman may have been married; she […]

LikeLike