Zheng Pingru is a Chinese heroine of World War II. Her story was tragically brief, and even today raises questions about the difficult role of women in war and occupation.

This episode is part of the series Women in Espionage.

Full Transcript

Back in episode 8.1, I complained that the pre-modern world had only hints of female spies. Well, such is no longer the case. We have now arrived at World War II, and there are female spies in every direction, both heroes and traitors, far more than I have the time or frankly the interest level to cover. So we’ll be doing the ones that piqued my interest. And first on the list is in the Asian theater of the war, which gets so little press coverage compared to the European theater, that I’m going to backtrack way before the birth of our current heroine to explain what’s happening in both China and Japan.

Like almost everywhere else in the world, China and Japan were seriously rocked by Western industrialization and imperialism, but they coped with it quite differently. In China, the court dug in its heels and tried to stay traditionally Chinese. When that didn’t work, they began slow reforms and modernization, with the predictable result that everyone was unhappy because the changes were either too fast or too slow or not the right kind of change. The last emperor of the once-mighty empire was forced to abdicate in 1912, but Louis XVIth would be jealous because at least they didn’t kill Emperor, possibly because he was only six years old at the time.

The new republic struggled (unsurprisingly), with multiple parties vying for control. The major ones, for our purposes, were the Nationalists (which ultimately became the party that withdrew to Taiwan) and the Communist Party (which ultimately got the upper hand on the mainland), leading to the tense situation that still exists today. But in the late 1930s, the Nationalists were still on the mainland, and more or less in charge.

The Japanese took an entirely different route. They also had dug in their heels and tried to stay traditionally Japanese, but it’s easier when you’re an island and not as tempting a target, so they were remarkably successful in their isolationism for a very long time. Until 1853, when U.S. Commodore Matthew Perry arrived with a heavily armed squadron of ships and said trade with us or else. Japan opened, grudgingly, but said to themselves: fine, we can play that game too. So they modernized incredibly quickly, using the Western powers as a model. Again, they were remarkably successful. Unfortunately, taking the Western powers as a model is a mixed package. I mean, yes to science, yes to technology, yes to a growing middle class, yes to the concept of democracy, even if application is a little sketchy. But no to the idea that all this makes us so much better than the rest of the world that we can do what we like with those savages. Japan did not draw that line, and there was China, so close, with such a history of disdainful superiority, and currently in such disarray.

Japan took Manchuria (the northern part of China) in 1931, which was not exactly good, but not the heart of the ancient empire either. Japan struck the heart on July 7, 1937, which was before Hitler even annexed Austria, much less Czechoslovakia, Poland, Denmark, Norway, France, Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, Greece, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Ukraine, Italy, Monaco, or Hungary. No one can say the man didn’t dream big.

Japan’s list is smaller, but then again, China is really, really big and so is the Pacific.

The attack came in multiple places. The Chinese chose to focus their response on Shanghai, and they put up a very good defense, holding the Japanese up until November. Then the Chinese army fled back west, leaving both Shanghai and the capital Nanjing unprotected. The Japanese occupied both. And their treatment of Nanjing is sometimes called the single worst atrocity of the war, in either the Asian or European theater. There are no hard numbers that everyone agrees on, but it is clear that the Japanese military had a complete and total breakdown of discipline, and it was more or less open hunting season on the Chinese civilians and POWs. The lowest estimates are 50,000 Chinese slaughtered within six weeks. The official Chinese tally is 300,000 in those same six weeks. Even for those who survived, the experience was scathing. It’s known as the Rape of Nanjing and that word is accurate in every possible sense.

The twenty-five or so foreigners who remained in the city bore their witness and did their best to help. And just to prove that history is never uncomplicated, they were led by a German businessman, a leader in the Nazi party. He got the Japanese soldiers to respect him by flashing his Nazi swastika armband. Germany, after all, was an ally of Japan.

I’m giving you this background to let you know that this was no civilized conflict between respected adversaries. This was war at its dirtiest and most vicious. And as always, those who lost the most were those who had absolutely nothing to do with the causes.

But our story today is back in Shanghai, where the situation was better, but not good.

In Shanghai, a Chinese city now occupied by Japan, the power struggle was extremely complicated. There were four major players in the game:

- The Chinese Nationalist Party. This was the party that had been running China when Japan arrived.

- The Chinese Communist Party. This group had been growing and challenging the Nationalists before Japan arrived and grew in strength when the Nationalists fumbled the defense so badly.

- The Japanese military police, which I hope is self-explanatory.

- The puppet government installed by the Japanese but made up of Chinese ex-Nationalists (a.k.a. collaborators).

These last two groups were running drugs and protection rackets. They did so for two good reasons: money and because the resulting chaos justified the occupation. The military could claim they were needed, what with all the crime. Someone had to keep things under control. It was, basically, a gangster city of the type I’ve seen in the movies but have been fortunate enough to avoid in real life (Edwards, 140-141).

All of the four groups were running spies against each other, and I’m not even counting the minor players like the spies for the Americans or the spies for the Europeans. And some of the spies were women.

Zheng Pingru was an ideal candidate. She was born in 1918, the daughter of a Chinese lawyer and his Japanese wife. According to Chinese naming conventions, the family name was Zhèng. Pingru was what we English speakers would call her first name, though it’s said after the family name.

Pingru grew up fluent in both Chinese and Japanese, and she knew important people in both communities.

When Shanghai fell to the Japanese, Pingru was 19 years old, a university student, and very beautiful. She acted with a local stage troop, played the piano, and sang Peking opera. You may not have heard much Peking opera, so I’m going to play you a clip. Not of Pingru, unfortunately. I’m unaware of any recordings of her, but this is just to give you a sample of the type of music she would have been making. It sounds quite strange to Western ears, but it is a historic art form recognized by Unesco world heritage. This particular singer is a male singer playing a female role, because until women weren’t allowed to participate until 1912 (DeVellis). Sometimes don’t change no matter which side of the globe you’re on. Sigh. Anyway, here’s the clip:

I’ll put some links on the website if you’re interested in the fabulous costumes that go with this singing. They make pretty much everything I’ve ever seen on stage look bland.

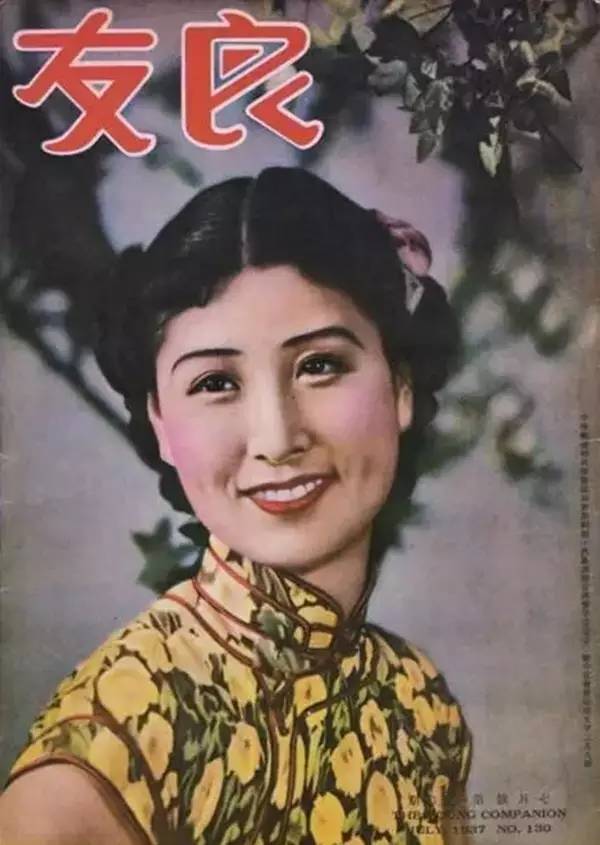

Whether you were properly impressed by that or not, Pingru was perfectly poised for glamorous career in entertainment. She was even locally famous. Her picture had been the cover photo on a local magazine just months before the invasion.

But of course the invasion changed everything. If she’d been in Nanjing, she probably wouldn’t have survived at all. But this was gangster-city Shanghai, full of spies and Pingrus’ background made her perfect. She was believable in either a Chinese or a Japanese setting, so the question was, who’s side was she really on? The answer to that seems to have been the Chinese side.

The Chinese Nationalists approached her as early as 1937, but she had no opportunity to act until 1939.

In that year, the Japanese caught a Nationalist leader, and the young, the beautiful, the talented Zheng Pingru went to plead clemency for him on behalf of his elderly wife.

The man she was pleading to was Dīng Mòcūn, the Chinese head of intelligence for the collaborator government working for the Japanese. The Nationalists knew him well, including his interest in young, beautiful women. Yes, he was 17 years older than Pingru. Yes, of course, he was married. That seems to have been a concern to absolutely no one. Except possibly his wife. I don’t know.

Pingru reminded Ding that she had been his student when he was a middle school principal. And by the way, my source just drops this without comment, but can I pause to say that it’s quite a career path to go from humdrum middle school principal to evil spymaster? I’m not sure I can think of anyone else who has achieved that. I mean, wow.

But for the Nationalists, this particular job was going to plan. Clearly Ding wasn’t big on the various ethics considerations involved because Pingru was the new girlfriend. The next step was the assassination.

On December 10, 1939, Pingru told her new handlers that she had a date with Ding. When their car arrived at her door, she was to convince him to come inside; where two men would be waiting for him. Pingru tried her level best, with all the allure she could muster, but Ding refused to get out of the car. Exactly why, I’m not clear, but he may well have felt threatened even without suspecting her in particular. The possibility of assassination was uppermost on the minds of everyone of consequence in Shanghai because it was, in fact, happening on a regular basis. Plan One foiled.

On the 21st, a new date, a new plan. While driving to the event, Pingru was to spontaneously convince Dīng to buy her a fur coat, which she did. A furrier’s shop was along the route, so there was an unscheduled stop, which they did. They were to enter the shop and the two assassins would follow them into the close quarters and open fire. But Ding noticed two men loitering near the entrance. An entirely justified paranoia struck him and he fled back to the car and drove off as they fired. It was not chivalrous, what with stranding his date on the street in a hailstorm of bullets, but it saved his life. Plan Two foiled.

To keep her cover, Pingru called Ding to offer tearful apologies for having inadvertently led him into danger over her foolish desire for a fur coat. Ding not only accepted her regrets, but also sent her money (Edwards, 144).

But a few days later when she arrived for another date, she was arrested, so he wasn’t as gullible as she had thought. For several weeks, they detained her and while you always wonder just how horrific that was, it seems to have been kinder than it might have been. She was allowed at least one phone call out to her brother, and she told him not to worry. The questions were put to her at least partially by the wives of the senior officials in the puppet government, which is a twist I would not have expected. More on that later.

Eventually, Pingru admitted that she had known about the assassins, but she claimed her motive was jealousy. She knew Ding had been seeing other women and she wanted revenge. Perhaps she hoped this motive would save her life. Even though Ding’s wife was one of her interrogators and could have held similar feelings.

In February, Pingru was told they were going on a picnic and she dressed up for the occasion. The fact that she found this believable is an indication that her imprisonment must not have been like, say, Mata Hari‘s, for example. But she realized her mistake when she recognized the park she had been driven to was a field outside the city which had previously been used for executions.

She turned to the men accompanying her and asked them not to shoot her in the face. Accordingly, she was shot in the chest in February 1940.

Pingru’s story would probably have slipped unnoticed into history, just one of hundreds of thousands of Chinese deaths in the war, except for all the controversy later.

By 1946, the war was over and the Japanese had lost, so it was time for the war crimes trials.

Ding Mocun had plenty on his conscience, but one of the charges was brought by Pingru’s mother and brother who stepped forward to demand justice for her.

According to them, Pingru was patriotic and heroic. She had sacrificed herself for China. Also, her brother claimed that Ding had threatened to kill her father if she did not cooperate with him, so she was ultimately virtuous, moral, and chaste herself, and she was his victim, not the other way around.

For his defense, Ding said, more or less, Zheng who? Apparently his life was so full of dazzling beauties he didn’t remember this one in particular. On prodding, he vaguely recalled having loaned his car to that girl a few times. She was the leach type, seducing rich men for what she could get out of them. He had no idea if she was really a nationalist spy, but if she was, he was filled with respect for such patriotism, God Bless China, or something to that effect.

Ding’s memory lapse might have been more believable if two of his associates had not remembered Zheng Pingru quite well. Oh yes, certainly they remembered her. A born seductress, utterly debauched, beautiful and deceptive to the core. No need for patriotism to explain her. She was just a real maneater. Even while imprisoned she tried to corrupt all the men. They’d had to send in their wives to question her because no man could control himself in her presence. Even Ding had wavered in his resolve, and she’d tried to kill him. Eventually, she was shot in the chest because even the executioner could not bear to mar such beauty (Edwards, 149).

Blah, blah, blah is what I have to say to most of that. Maybe she did try to seduce her captors, but that does not make her immoral. It makes her desperate. That was her only weapon of self-defense. And anyway, these men had obvious reasons to lie. So did their wives, who were also on trial and denied any involvement whatsoever (Edwards, 153).

The tribunal was as unimpressed as me. Dīng was found guilty and sentenced to death. There’s little controversy about that. But Pingru is still controversial.

As early as 1945, she had already been compared to Mata Hari, but if you ask me, the comparison is really not apt. Mata Hari was a prostitute who reluctantly and inexpertly got dragged into espionage that she wasn’t actually interested in and ultimately wasn’t any good at either. She had no political loyalties. She had always been international and self-serving.

But there is no evidence that Pingru would ever have chosen prostitution on her own. She had a career ahead of her before war ever broke out. But it did break out. All over China women took jobs as spies, and it was overtly expected that they would use every resource at their disposal to fulfill their assignments. In fact, married women were not eligible for jobs in this role, presumably because their husbands would be humiliated by the work required (Edwards, 138-139).

The nature of the job left these women open to criticism afterwards. Was she a shameless hussy, eager for sex with any rich man? That would make her both immoral and a traitor to China. Or perhaps a different take: A fictionalized novel of her, later made into an erotic movie, portrayed her as falling in love with Ding. And that’s why the assassination attempt failed because when it came down to it, she loved him more than she loved China.

The remaining Zheng family members were outraged. In their view, Pingru was not a sex spy. She was an innocent girl blackmailed by a monster, a tragic hero for China.

Since she died so young, we will never know what she would have said for herself, and the truth may well be somewhere in between: just a girl caught in a difficult situation, doing the best she could at the time. Author Louise Edwards concludes her telling of Pingru’s life with these words:

The reality of the life of this complex woman is difficult to determine . . . Large sections of the population want to imagine [women like her and Mata Hari] as highly sexualized, beautiful, glamorous, dangerous and duplicitous. At the same time, the memorializing of the women must also include a considerable component of rectifying their soiled sexual reputations. Declaring them to be innocent victims of bigger games is the only caveat available in the face of overwhelming evidence that they were in fact ‘sleeping with the enemy’ . . . All people living in occupied regions are forced into a daily engagement with the enemy in order to achieve some semblance of order in their lives, [but] once the enemy is defeated, this uncomfortable reality is rapidly erased from public memory and official history . . . In the aftermath of war, women are frequently judged for their sexual activity during the conflict while men escape this form of scrutiny.

(Edwards, 156-157)

You can let me know what you think of Zheng Pingru on Twitter @her_half or on Facebook at Her Half of History or in the comments below. Come back next week for a spy who doesn’t get executed at the end. Lise de Baissac’s story is more like a fairy tale, actually. Don’t miss it. Thanks!

Selected Sources

Bowblis, John. China in the 20th Century. King’s College History Department, 2000, departments.kings.edu/history/20c/china.html. Accessed 20 Sept. 2022.

DeVellis, Steven. “The History of Beijing Opera as a National Chinese Art Form – Global Theater.” Global Theater, Colgate University, 23 Apr. 2018, cducomb.colgate.domains/globaltheater/asia/the-history-of-beijing-opera-as-a-national-chinese-art-form/#:~:text=Women%20were%20forbidden%20by%20law,female%20performers%20was%20officially%20lifted.. Accessed 23 Sept. 2022.

Edwards, Louise P. Women Warriors and Wartime Spies of China. Cambridge, United Kingdom ; New York, New York, Cambridge University Press, 2016.

GBTimes. “Peking Opera | an Introduction (Hello China #13).” YouTube, 2 July 2012, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PnMRIzpO4nU.

“Japan’s Foreign Relations and Role in the Late 20th Century | Asia for Educators | Columbia University.” Columbia.edu, 2009, afe.easia.columbia.edu/special/japan_1950_foreign_relations.htm. Accessed 20 Sept. 2022.

Office of the Historian, Foreign Service Institute. “Milestones: 1830–1860 – Office of the Historian.” History.state.gov, history.state.gov/milestones/1830-1860/opening-to-japan#:~:text=On%20July%208%2C%201853%2C%20American. Accessed 20 Sept. 2022.

Unesco. “UNESCO – Peking Opera.” Ich.unesco.org, 2010, ich.unesco.org/en/RL/peking-opera-00418.

I found this so fascinating– Thank you, Lori. 🧡🧡🧡

LikeLike