I had way too much material this time, so this is the cut version of this episode. If you are interested in more about Emma Smith, the murder of Parley P Pratt, the first female State Senator in the country, and so much more, then please head to the Patreon page, where I have placed the uncut version for your reading or listening pleasure.

From the 21st century it is hard to grasp just how big an issue polygamy was in 19th century America. From this distance, slavery was the big moral issue. But at the time, slavery and polygamy were linked. The very first Republican party platform, written in 1856, declared their position in no uncertain terms: “it is both the right and the imperative duty of Congress to prohibit in the Territories those twin relics of barbarism—polygamy and slavery” (American Presidency Project).

Pro-slavery advocates linked it just the other way around.

In the interests of full disclosure, I have Mormon polygamous ancestors. That undoubtedly colors how I approach this, but I have done my best to stick to academically respectable sources, all listed below.

Non-Mormon polygamy has a long and varied history. In a landmark sociology study, researchers found that 84% of 185 cultures allow some form of polygamy (Kilbride, 41), so in one sense the real question isn’t why did Mormons have polygamy, but why Americans in general didn’t?

Polygamy fell out of favor in Europe in the Middle Ages. Martin Luther thought polygamy was a better than divorce, but he didn’t publish that view because he thought new converts wouldn’t like it. When English Henry VIII wanted to marry Anne Boleyn, divorcing Catherine was not the only legal remedy he considered. Bigamy was on the table too. But what he rammed through was divorce. Catholics did not actually prohibit polygamy until 1563 (Kilbride, 64-65).

Early Mormon Polygamy (Protopolygamy)

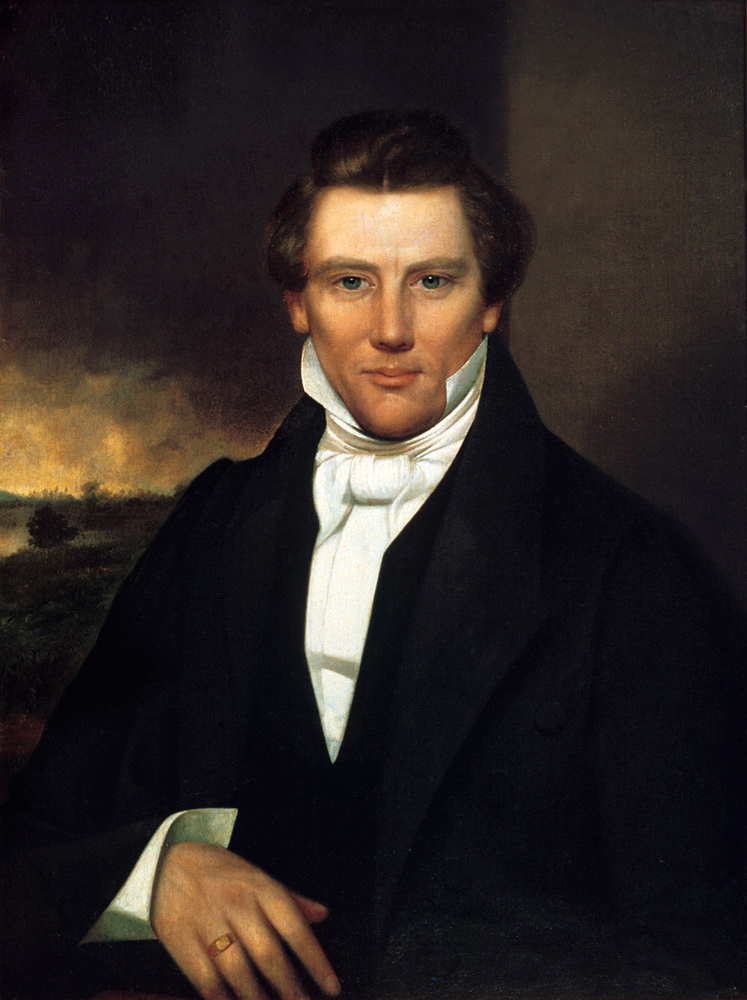

By the time Joseph Smith was born in 1805, polygamy was definitely something uncivilized foreigners did. Not us enlightened, Christian folks in the land of the free.

Joseph Smith formally organized the Church of Christ in 1830 and later changed the name to the more specific Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Doctrine & Covenants 115:4). The nickname Mormon refers to a figure in the Book of Mormon, a book which Joseph Smith said God had helped him translate as another work of scripture, comparable to the Bible. Early church members embraced the name Mormon. More recently, the church prefers the official name, but since the nickname is accurate for the time period I’m covering, I’m using it.

Early Mormon weddings were not polygamous. The 1835 Doctrine and Covenants of the church told officiators to say to the couple “you both agree to be each other’s companion, husband and wife, observing the legal rights belonging to this condition; that is keeping yourselves wholly for each other, and from all others during your lives.” The couple was supposed to say “Yes” (Doctrine & Covenants, 1835). Notice that the wife does not promise to obey, and chalk one up for old Joe Smith here.

Joseph himself wrote next to nothing about polygamy, but according to later second-hand accounts, he asked God how it was that the Old Testament prophets are called righteous, even though they had multiple wives, left, right, and center. In the world Joseph knew, that was the very height of not being righteous, so what gives?

In response, God told him that polygamy was not sinful if God authorized it. And yes, God expected it of his chosen servant Joseph Smith and other church leaders. Since the general public was not going to accept that, the early polygamous marriages were done in secret, which makes it pretty difficult for the historian. There aren’t many contemporary records, and none are as detailed as we would like.

Cynics both then and now assume that Joseph Smith invented this religious justification so that he could be a sexual predator. I have no intention of debating faith vs. doubt here, but if lust was the one and only reason, then Joseph made several very strange choices. It is true that some of his wives fit the expected victim profile: young, beautiful, unprotected. But some of them do not.

Patty Sessions was 47 (Ulrich, 127). I want to assure you that I think 47 is a very attractive age, plenty of life ahead and all that. But consider that life expectancies were shorter than now, the living was hard, the cosmetics were limited, Joseph himself was only in his mid-thirties, and he had a city of 10,000 people hanging on his every word. You just have to wonder why a sexual predator would include Patty Sessions. And she isn’t even the oldest (Ulrich, 112).

Besides the age thing, there’s the unprotected thing. American masculinity of the time prided itself on protecting their helpless womenfolk. Again, some of these women were unprotected, but many did have a man in their lives who could and would have protected them. Eliza R Snow (age 38) had a father and a brother. Zina Jacobs (20), Presendia Buell (31), and Patty Sessions (47) had living husbands (Ulrich, 127). Yes, husbands. For some of these women, it was bigamy in both directions.

Which brings me to another puzzler about what these marriages even meant. Since it was all hush-hush, you didn’t call yourself Mrs. Smith, you didn’t set up house together, and you didn’t quit your day job, even if your day job was being wife to someone else.

Most of these women did not keep a diary, but even if they did, 19th century diarists don’t write about sex. Historians can only deduce sex by counting backwards from the births. Given that Joseph married somewhere between 27 and 49 women, mostly between 1841 and 1843, we would expect to find a good two dozen babies appearing in a very predictable timeframe.

But we don’t.

Only a small handful were ever even alleged to be Joseph’s children by way of a polygamous wife. Many of those died young, but some have living descendants, and yes, some DNA tests have been done. They were negative (Perego). Meanwhile, Joseph proved his fertility many times over with his legal wife, Emma, including during this very same time period.

The 19th century did have some methods of birth control and abortion, but all of them were chancy, and none of them were approved of by Mormons. So using the only measure we have available, Joseph doesn’t seem very effective as a sexual predator. Which is not the same as proving that there was zero sex involved. That’s unprovable, and certainly Joseph never made a direct statement saying so. You’d think if he could have, surely he would have?

But if even a portion of the people involved in early polygamy thought it was a purely religious ceremony with no physical component, then it would explain a lot. Like why so many women were willing to do it, even though they’d all been raised to believe that a woman’s chastity was her most important possession. Like why the husbands, fathers, and brothers not only didn’t beat Joseph Smith to a bloody pulp, but actually delivered his proposals to their female relatives (Bushman, 325, 440) and served as witnesses and officiators (Bushman, 498). Like how Emma Smith sometimes said this was okay; she was all right with it (Bushman, 494). Admittedly, there were other times when she didn’t say that, but some of the time she did.

You may be wondering, if these marriages didn’t mean any of the things we traditionally associate with marriage, what on earth did they mean?

In modern Mormon theology, the defining trademark of the marriage ceremony is that it doesn’t end at death. Through what Joseph called the “new and everlasting covenant,” families (including children) are sealed to each other for time and for eternity on the theory that heaven wouldn’t really be heaven without those you love. If someone dies before the ordinance is performed, that’s okay. It can be done by proxy afterwards. Essentially it’s about keeping happy families together eternally.

But early church members don’t seem to have understood all of that, and maybe not any of it. Joseph didn’t get or give all this in one clearly written FAQ. The “new and everlasting covenant” in his time was a euphemism for plural marriage, and the revelation on it didn’t say what it meant in terms of sex, naming, financial support, or exclusivity. It did say you had to accept it to be saved.

I imagine the women had an awful lot of questions, and I imagine they didn’t get a lot of clear and consistent answers. Basically, it was confusing, and nobody was prepared to talk about it much, not even in a diary.

On the day Eliza R Snow married Joseph Smith, she wrote in her diary, “This is a day of much interest to my feelings. Reflecting on past occurrences, a variety of thoughts have presented themselves to my mind” (Ursenbach, 394-395). She gives no details whatsoever. We only know this was the wedding day because she signed an affidavit saying so years later.

Emmeline Harris was 18. She had a husband who had left to find work. She was beginning to suspect he was not coming back, so she does fall in the category of young and unprotected. On the day she married Newel K. Whitney, she wrote in her diary, “This day like all others is full of trouble sorrow and affliction…O that I had a mother or sister to advise me but I am cut short of all these blessings” (Wells).

Could this be the terrified anguish of a girl who had just been manipulated into a sexual encounter with an older man? Yes, it could. It could also be the terrified anguish of a girl whose husband had left her followed by a baffling religious ceremony, no assault required. Two things only are certain: she did not give birth nine months later and her subsequent entries are full of grief for her first husband. She wrote, “Had I been treacherous I might have expected as much but God knows I have ever been true to him… God grant that he may soon return for my heart is braking [sic]” (Wells, Feb 28, 1845).

Clearly, Emmeline did not think that whatever she had said or done with Newel K Whitney was incompatible with her first, very conventional marriage.

Scandalous Accusations and Furious Denials

Meanwhile, the pressure on Joseph Smith boiled over. John C Bennett was a high-ranking officer of the church. He knew about plural marriage but was not authorized to practice it, which did not stop him from secretly telling various women that the Prophet Joseph had said it was no sin to have sex with him because they were his spiritual wives. Several women confessed afterwards (Derr, 12).

When Joseph called him out for this behavior, Bennett left town, wrote an exposé of Mormonism, and went on a very public book tour. The American public loved scandal as much then as they do now, so they lapped it up. Here’s an excerpt from the book:

The Mormon Hierarchy are guilty of infidelity, deism, atheism; lying, deception, blasphemy; debauchery, lasciviousness, bestiality; madness, fraud, plunder; larceny, burglary, robbery, perjury; fornication, adultery, rape, incest; arson, treason, and murder; and they have outheroded Herod, and out-deviled the devil, slandered God Almighty, Jesus Christ, and the holy angels, and even the devil himself.

(Bennett, 257-258)

The venom was mostly for Joseph, but Mormon women also felt impugned. By 1844, Emma Smith had reached her limit. She gathered the female Relief Society of which she was president and delivered some fiery rhetoric herself, concluding with ” let polygamy, bigamy, fornication, adultery, and prostitution be frowned out of the hearts of honest men” (Derr, 156). Emma delivered her speech four times to unanimous approval each time (Derr, 152).

Most of the hearers were reassured: the rumors were all smoke and no fire, nothing to worry about. Those who knew more may have agreed because their plural marriages were not sexual. Or if they were sexual, they were authorized by God. So not adulterous.

The word that gives pause is Emma’s including polygamy in the list of things to be frowned out. By 1844, she most definitely knew what Joseph was doing.

But whatever Emma meant, the more people learned about plural marriage, the bigger a hypocrite Joseph looked. If lust was his motivation, he was surely regretting his methods. 19th century America would have forgiven him for straight up adultery much faster than for dignifying those women with the title of wife. Eventually, he was assassinated by an angry mob. The enemies of Mormonism breathed a sigh of relief. Surely, without Joseph the whole religion would fall apart.

But it didn’t.

After Joseph’s death, plural marriage was an open secret. Mormons didn’t admit it to outsiders, but if you were a member, you knew. Plural marriage actually got a major boost out of Joseph’s martyrdom. Accepting his system of plural marriage was now a badge of loyalty. And these plural wives had babies. The system had changed. The opposition had not.

In 1846, Mormons left Illinois because the alternative was to be driven out. The new president Brigham Young led his band of refugees to what is now Utah.

Once settled in Utah, Mormon polygamy was open and above board and after 1852, Brigham Young decided it could also be acknowledged to the world at large. No more secrecy.

Brigham Young installed his wives in one house, each with their own room. But the more usual pattern was that each wife had her own separate house, and the husband moved between them. This had the effect of reducing friction between the sister wives, but it also had another unexpected consequence. Since the husband was frequently absent at another of his homes, the wife lived more or less independently much of the time. You can view this in either of two ways: either these oppressed women were the ultimate in shouldering the double burden because dad was almost always absentee. Or these were strong modern women who bought and sold property, set up businesses, made parenting choices, and did all kinds of things most 19th century women couldn’t do because there was always a man throwing his weight around.

In Defense of Polygamy

In this period, the argument that polygamy was bad because it oppressed women is complicated. It is certainly true that polygamy was an unequal relationship based on a double standard about sexual behavior. It is also true that some women were jealous of their sister wives, and some were lonely. But in other ways, Utah already was what women’s rights activists were agitating for.

These activists had a big beef with the English common law principle of coverture. Under coverture, a husband and wife were the same person, by which we mean, they were the husband. Effectively, this meant married women could not enter into contracts, could not sue in court, could not control their own property, and couldn’t retain their own wages because husbands covered all that for them.

Utah abolished English common law in the territory’s very first congressional delegation. Their purpose was to get rid of the bigamy penalties, but coverture went out the door too (Ulrich, 342).

Another gripe for women’s rights activists was how hard it was for a woman to get a legal divorce. In Utah, neither legal marriage nor divorce was really a thing. It was entirely a church matter, and the church allowed divorce. You didn’t have to prove guilt. As head of the church, Brigham Young signed 1,645 divorce certificates (Ulrich, 440), including for one of his own wives, and several for the wives of Wilford Woodruff, a future church president.

You may well wonder how these polygamous men could afford to set multiple women up in their own houses. And your suspicion is correct. Wealthier men got the wives. Hard luck on the poor men, but from a cold-hearted woman’s perspective, that’s another check in favor of polygamy. Studies throughout the world show that financially speaking, a woman is often better off as plural wife of a rich man than as the only wife of a poor man (Bennion, 9). Mormon polygamy was no exception: the economic effect of polygamy was to redistribute resources from wealthy men to poor women (Daynes, 92).

Women’s rights and finances are a motivation modern people understand, but those were not the arguments used by Belinda Marden Pratt who published a “Defense of Polygamy” in 1854. Instead she pointed out its scriptural basis. She pointed out that the purpose of marriage was procreation and polygamy maximized that by not wasting a man’s procreative power at times when a woman could not conceive. She pointed out that monogamous communities left many women as old maids and spinsters, either destitute or dependent on other relatives. She pointed out that men and women are built differently. In polygamous societies, no woman was driven to prostitution in order to eat and no man reached for a prostitute to satisfy his sexual needs. And finally, she said she loved and appreciated her seven sister wives. They were family (Pratt).

You may find some of Belinda’s arguments unconvincing. But the underlying assumptions were right in line with mainstream America: The Bible is always right, the purpose of marriage is procreation, women don’t have a sex drive, men can’t be expected to control theirs, and nobody wants to be an old maid. None of that was in any way surprising, and Mormons would continue to propound Belinda’s arguments for decades. They would also point out that the mainstream had de facto polygamy anyway: lots of married men with mistresses on the side. The difference was mistresses could be chucked at any point and their children couldn’t inherit. Mainstream America was not much interested in discussing that particular argument.

Of more interest from a modern perspective is the question of consent. Modern society tends to have a much more permissive view of various sexual arrangements as long as everyone involved is a consenting adult. So the question is did Mormon women have the ability to say no?

I can’t speak to every woman’s experience, but we have plenty of examples to prove that some women could and did. When Joseph Smith tried to teach Sarah Kimball about plural marriage, she told him to teach it to someone else (Ulrich, 575). She remained a very prominent, monogamous member of the church. Decades later Mary Ann Stearns Winters wrote that when she read an explanation about the Biblical origins “I decided that the principle must be true, coming from that source—and also, though right for others, not for me—was my firm conclusion. And though steeled against it for myself, I always honored and respected those living in it” (Relief Society Magazine 1916, 578).

Some women didn’t wait for a proposal. When Emmeline Harris Whitney found herself in Utah with a baby and a dead husband, her prospects in most places would have been bleak. But in Utah, she looked around at the respectable businessmen of the city, and she chose the one she preferred. She wrote Daniel G Wells a business letter and proposed marriage. He accepted. She joined a gaggle of wives. It is true that her diary shows a longing for closeness that wasn’t there. She was a charity case, and she knew it. But she and her baby weren’t penniless.

From a modern perspective the real consent concern is age. Marriage is a market. When there is more demand for wives than there is supply, the age goes down. All of 19th century America accepted marriage at younger ages than we would, but in Utah it was even younger, and fell to the point that even Brigham Young was concerned (Ulrich, 539).

Federal Opposition to Polygamy

The politicians in Washington didn’t care about age so much, but they did not like polygamy. In 1862, the newly formed Republicans were in charge (at least in the North), and Congress outlawed polygamy in the territories, which had absolutely no impact whatsoever. Mormons didn’t register their marriages with the government, and no Mormon jury was going to convict (Bennion, 4). The feds were a little busy with a thing called the Civil War so enforcement didn’t happen.

When the war was over, the women’s rights movement thought they had the correct leverage. If Mormon women had the vote, they would vote out this super patriarchal system, right? Plus, it would set a precedent for women’s suffrage in other places. Two birds, one stone.

When the question came before the Mormon men of power, they said yeah, okay, sure. It was hardly a fight at all. Utah women voted starting in 1870. They did not vote polygamy out. On the contrary, they defended it. Women’s rights leaders may have been surprised, but they couldn’t afford to be picky about their allies. One of the most vocal was none other than Emmeline Wells. No longer a frightened teenager, she had grown into a powerhouse of a woman. Among other things, she ran the Women’s Exponent newspaper, a passionate and articulate voice for both women’s rights and polygamy (Ulrich, 598).

By the 1880s, the federal government considered their job done with respect to former slaves, and they could now devote their full energy to the other relic of barbarism. The Edmunds-Tucker Act of 1887 disincorporated the Mormon church, dissolved the territorial militia, and rescinded women’s right to vote (Ulrich, 589). Polygamy was now a felony, and it didn’t matter that Mormons didn’t register their marriages because cohabitation was offense enough (Bennion, 4). Over 1300 men were jailed (Bashore). Many more were in hiding. They couldn’t work, couldn’t support their families, couldn’t transact church business, couldn’t preach.

The Manifesto

The President of this rapidly disintegrating organization was now Wilford Woodruff. On October 6, 1890, Wilford Woodruff gave an official declaration, later known as the Manifesto. It said “I hereby declare my intention to submit … We are not teaching polygamy or plural marriage, nor permitting any person to enter into its practice” (Doctrine and Covenants, Official Declaration 1). Forty-six years after Joseph Smith’s death, it was over.

Some women were thrilled. But many others wept, and for good reason. Lorena Washburn Larsen, a second wife with young children said:

My feelings were passed [sic] description … My husband walked out without saying a word, and as he walked away I thought, oh yes, it is easy for you, you can go home to your other family and be happy with her … I sank down on our bedding and wished in my anguish that the earth would open and take me and my children in.

(Lorena W. Larson Papers)

Wilford Woodruff said he had prayed and that God had commanded him to do this, but it sure looked like a craven cop out to secular authority. New polygamous marriages were obviously forbidden, but no one gave clear instructions on what the Manifesto meant for current polygamous marriages. Each family was left to figure it out.

In contrast, the federal government was pleased with the Manifesto. As a reward, they finally granted Utah statehood in 1896.

Post-Manifesto Polygamy

But as time passed, the government suspected the Manifesto was just a front, while the church continued to sanction new polygamous marriages. And it turns out they had good reason to be suspicious. New plural marriages did significantly decline, but not all the way to zero.

Here’s just one example. Wilford Woodruff had a son named Abraham Owen Woodruff. He married his first wife Helen May Winters in 1897, well after the Manifesto. Owen was called as an apostle in the church. While traveling for the church, he met Eliza Avery Clark. He asked her father for permission to marry her. Both Avery and her father were shocked, and her father said no, not unless it’s church sanctioned. But after four months of prayer and secret meetings, Avery said yes. They were married in 1901.

Wilford Woodruff was already dead, so there’s no knowing what he would have thought. There is no evidence that the current president approved the marriage, but then again there is also no evidence that he didn’t (Snyder, 21). Since this marriage was both illegal and against church policy, secrecy was vital.

In 1903 Owen gave Avery a home of her own in Mexico. The town had other polygamous wives, but of course he would rarely be there, and her other friends and family were far away. “Loneliness enveloped me” was what Avery said (Snyder, 28).

In 1904, Owen and Helen visited Avery on their way to Mexico City before heading off on a mission to Germany. Ostensibly this was church business. But some church members, including my own ancestor, Francis Marion Lyman, had recently been hauled up to Congress to answer charges that they were still cohabiting with multiple wives. Francis cheerfully admitted that he was and intended to continue to do so (Snyder, 34). But at least his marriages predated the Manifesto.

Owen’s position was far worse. He needed to flee the country. Avery was hurt to be left behind (Snyder, 36). But in the end, she was lucky. Owen and Helen both died of smallpox in Mexico City, within two months of leaving Avery (Snyder, 36-37).

A little backsliding notwithstanding, times really had changed. Utah was no longer isolated, and Mormons wanted enough respectability to be a player on the world stage. Even before the Manifesto, polygamy was on the decline, partly because young people liked the newfangled idea of marrying for love of all things (Daynes, 173). Polygamy didn’t really fit into that world view.

Most church members gradually modified their understanding of Joseph’s revelation on the new and everlasting covenant: Polygamous marriage was still God’s plan, but at certain times, God knew that polygamy was temporarily inexpedient, so monogamy was fine. During the 20th century, the understanding gradually reversed. According to the Church’s official website, monogamous marriage is God’s plan, though He may at times authorize a different arrangement, as he did in the 19th century. The church became a staunch champion of the Victorian ideal of family life. Yes, I get the irony.

For those without such flexible thinking, this was outright apostasy, and they said so. In 1910 the church began excommunicating those who still made new polygamous marriages, but not those who quietly maintained the old ones. Many of the excommunicated formed their own churches and still exist today.

In recent years, law enforcement generally ignores what consenting adults choose to do. Adultery and cohabitation are no longer punishable crimes, so polygamy is difficult to prove. They do pursue cases of child abuse, statutory rape, violence, and financial fraud, all of which have led to high profile cases against modern polygamists.

Some scholars and social workers that think polygamy should be legal. Marriage equality is already far more open than the 19th century ever dreamed of, and polygamy can be argued as the next frontier. Others argue that secrecy fosters abuse, statutory rape, violence, and financial fraud. If polygamy were legal, such things would be easier to see and stop (Bennion, 11).

I have no opinion on modern policy, but I mention it because the argument helps make a little sense of 19th century polygamy. You will obviously form your own opinions, but I am not much bothered by the vast majority of polygamous marriages which happened in the middle, when everyone knew and understood what they were getting into. I am much more troubled by the very early and the very late marriages, where the woman didn’t know what it meant, but it was spiritually essential, and yet it was all so secret that she couldn’t ask her friends and family about it, either before or afterwards. That part is troubling.

On the other hand, it is hard to see how the on and off ramp of something so fundamental as a system of marriage could be anything but bumpy. And perhaps the same goes for a new religion.

Selected Sources

American Presidency Project. “Republican Party Platform of 1856 | the American Presidency Project.” Www.presidency.ucsb.edu, 1856, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/republican-party-platform-1856. Accessed 12 Feb. 2023.

Bashore, Melvin L. Life behind Bars: Mormon Cohabs of the 1880s. Utah Historical Quarterly, Volume 47, Number 1, 1979, issuu.com/utah10/docs/uhq_volume47_1979_number1/s/131084. Accessed 16 Feb. 2023.

Bennett, John Cook. The History of the Saints. Boston, Leland & Whiting, 1842, archive.org/details/historyofsaintso00benne/page/n271/mode/2up?q=murder. Accessed 14 Feb. 2023.

Bennion, Janet, and Lisa Fishbayn Joffe. The Polygamy Question. University Press of Colorado, 1 Mar. 2016.

Bushman, Richard Lyman. Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling. New York, Vintage Books, 2007.

Daynes, Kathryn M. More Wives than One. University of Illinois Press, 2001.

Derr, Jill Mulvay, and Matthew J Grow. The First Fifty Years of Relief Society. Church Historian’s Press, 2 Feb. 2016.

“Doctrine and Covenants, 1835,” p. 251, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed February 8, 2023, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/doctrine-and-covenants-1835/259

Green, Nancy. “Martha Hughes Cannon.” PBS Utah, July 2012, http://www.pbsutah.org/pbs-utah-productions/shows/martha-hughes-cannon/. Accessed 22 Feb. 2023.

Kilbride, Philip Leroy. Plural Marriage for Our Times: A Reinvented Option? Westport, CT, Bergin & Garvey, 1994.

Lorena W. Larsen papers; Lorena Larsen autobiographical papers, undate; Church History Library, https://catalog.churchofjesuschrist.org/assets/aa6cb033-5e03-43c9-8c19-432e66bd9dce/0/4 (accessed: February 20, 2023)

Madsen, Carol Cornwall. “Emmeline B. Wells: ‘Am I Not a Woman and a Sister?’” Brigham Young University Studies 22, no. 2 (1982): 161–78. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43040896.

National Park Service. “Women’s Suffrage in Utah (U.S. National Park Service).” Www.nps.gov, http://www.nps.gov/articles/000/women-s-suffrage-in-utah.htm#:~:text=Whatever%20the%20motivations%2C%20Territorial%20Secretary. Accessed 16 Feb. 2023.

NPR. “How Mormon Polygamy in the 19th Century Fueled Women’s Activism.” NPR.org, http://www.npr.org/2017/01/17/510246850/how-mormon-polygamy-in-the-19th-century-fueled-womens-activism. Accessed 7 Feb. 2023.

Perego, Ugo A., et al. “Resolving a 150-Year-Old Paternity Case in Mormon History Using DTC Autosomal DNA Testing of Distant Relatives.” Forensic Science International: Genetics, vol. 42, Sept. 2019, pp. 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsigen.2019.05.007. Accessed 3 Sept. 2021.

Pratt, Belinda Marten. Belinda Marden Pratt’s Defence of Polygamy, 1854. 12 Jan. 1854, jared.pratt-family.org/parley_family_histories/belinda_marden_defense.html. Accessed 16 Feb. 2023.

Relief Society (Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints). The Relief Society Magazine, 1916. General Board of the Relief Society, 1916, archive.org/details/reliefsocietymag03reli/page/578/mode/2up. Accessed 18 Feb. 2023.

Ritchie, WMF, and Roger A Pryor. “Black Republicans on Polygamy.” Richmond Enquirer, Volume 53, Number 17, 27 June 1856, virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=RE18560627.1.2&srpos=3&e=——-en-20-RE-1–txt-txIN-polygamy+abolition——-. Accessed 12 Feb. 2023.

Snyder, LuAnn Faylor, and Phillip A Snyder. Post-Manifesto Polygamy: The 1899-1904 Correspondence of Helen, Owen, and Avery Woodruff. Utah State University Press, 30 Apr. 2009.

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady. “Overland Letters: The City of the Saints.” The Revolution, 13 July 1871, digitalcollections.lclark.edu/items/show/9791. Accessed 16 Feb. 2023.

Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher. A House Full of Females : Plural Marriage and Women’s Rights in Early Mormonism, 1835-1870. New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 2017.

Ursenbach, Maureen. “Eliza R. Snow’s Nauvoo Journal.” Brigham Young University Studies 15, no. 4 (1975): 391–416. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43040580.

Wells, Emmeline. “The Diaries of Emmeline Wells.” http://www.churchhistorianspress.org, 24 Feb. 1845, http://www.churchhistorianspress.org/emmeline-b-wells/1840s/1845/1845-02?lang=eng#title6. Accessed 13 Feb. 2023.

Very interesting read! It looks like you have done a lot research.

Blessings!

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

After reading The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints’ most recently published Saints history, I am not shocked or disagreeable about the anything you have said. But after being an active member my entire life, some of these things are new knowledge to me– new as of the last seven years or so.

It’s a complicated issue involving lots of people, lots of time, and lots of different opinions. You covered it well, Lori.

LikeLike

I hope when you say it’s new knowledge, you mean the details are new, not the basic fact of polygamy! (I’ve met some members who didn’t know for a REALLY long time.) Thanks for taking the time!

LikeLike

Yes, the details. I knew, as a kid, that we as a church did polygamy. I also have polygamous ancestors. I’m descended from a polygamous marriage. Had it not existed, I would not be here today.

LikeLike