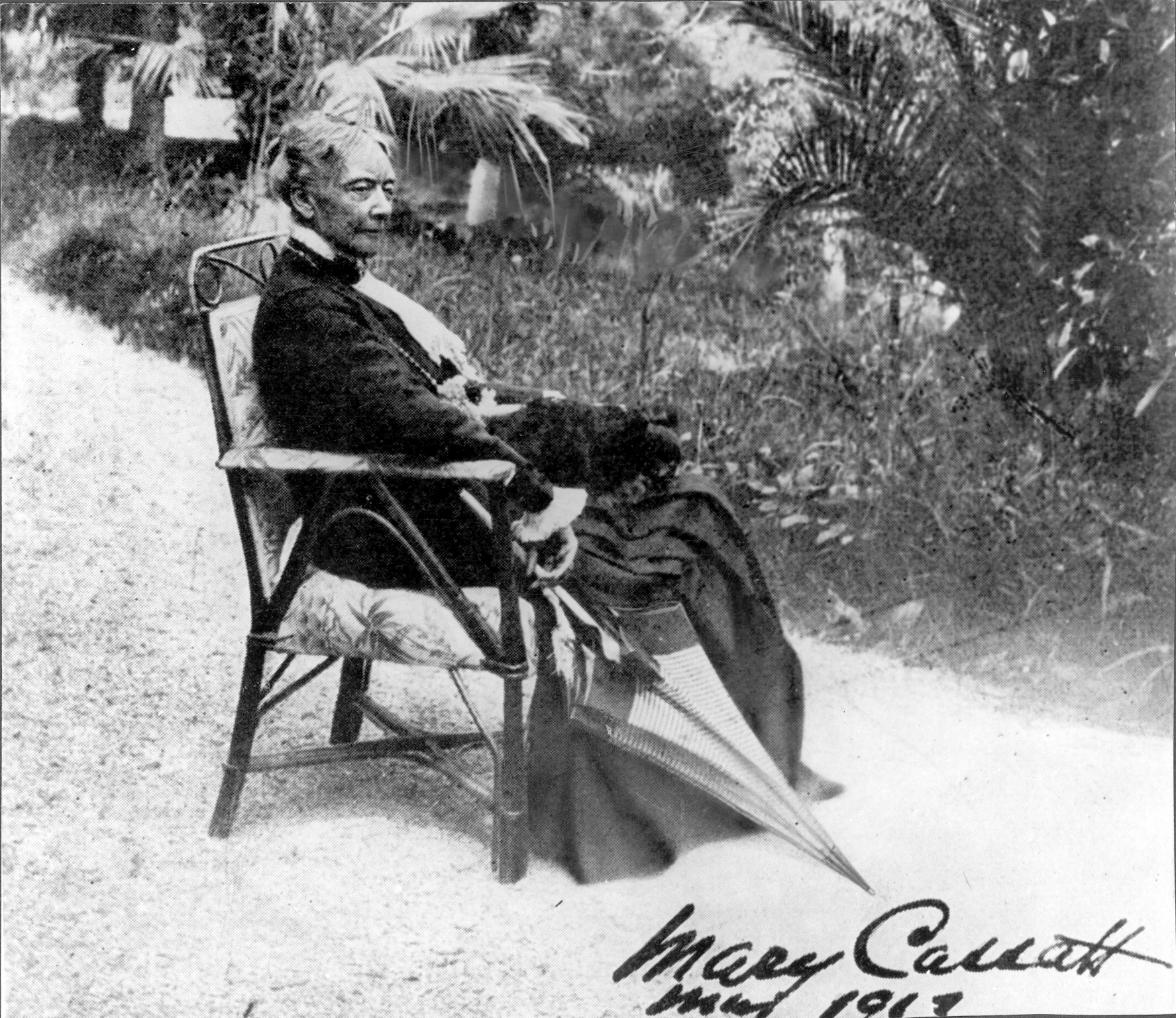

My research on Mary left me with more questions than answers. She is a bundle of seeming contradictions. She’s championed as one of America’s greatest painters, and yet she spent most of her life avoiding America. Her work glorified gentle motherhood, and yet she herself showed not the slightest interest in becoming a mother. She insisted on her femininity but was furious when her work was judged on its femininity. She lived a lifestyle that appeared rich, but maybe wasn’t so very rich.

Overall, you just get the sense that Mary Cassatt could be many different things depending on what light you choose to view her in. Which I suppose is entirely appropriate for an Impressionist painter. This then is maybe not her definitive story, but some impressions of Mary Cassatt:

A Childhood in Europe

Mary was born on May 22, 1844, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She can’t have remembered Pittsburgh much because by age seven her family had moved to Europe. Why? Because her father was restless, and his modest income stretched farther there. This is not the first time in this podcast we’ve encountered a move like this, and I gotta say it: I clearly live in the wrong century. Oh, for the days when middle-class people could live in hotels in the great cities of Europe because it was cheaper than staying at home, and no one cared what kind of visa you had.

Of course, I recognize that this wasn’t true for everyone. But by and large the people who did this did not recognize that. They thought they were normal.

Anyway, the Cassatts tripped their way through France and Germany. Mary became fluent in both languages. And then when she was eleven, it was back to the US, this time to Philadelphia.

An Arts Education

In 1861, Mary entered the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. The academy had girls from the nice families of America, which is to say that these girls had no intention of going pro. They were simply becoming accomplished before reaching the age of marriageability. That is undoubtedly what Robert Cassatt intended for his daughter as well. Later in life Mary claimed that when she told him her plans to be a professional artist, he said he would rather see her dead (Hale, 31).

But if you look at the evidence, that’s not what his actions say. He allowed her to graduate and then paid for her to go to Paris and study with the masters there. By 1868, she had a painting accepted by the French Salon. It’s The Mandolin Player and it’s beautiful, but not in the style Cassatt would later become famous for. It’s not an Impressionist painting.

The next few years saw Mary flitting through France, Italy, Spain, Holland, Belgium. Basically living my dream, except with a lot more art. Oh, and there was a brief and grudging trip to the US, when the Franco-Prussian War made it clear Europe was maybe not so stable. She visited Chicago then, just in time to have the Great Fire destroy some of her paintings, so that part’s maybe not my dream after all. But you can start to see why some starving artists thought she was rich.

Meeting the Impressionists

By 1873, Mary was almost 30. There was not and never had been any man worth mentioning in her life. Other than her father and brothers, I mean. But now she was back in Paris, and she walked by an art shop and she saw not a man, but a piece of art. It was La Répétition de Ballet by Edgar Degas, and Mary convinced the friend she had with her with her to buy it on the spot (Hale, 54).

This, by the way, would become a trend. Despite her lifestyle, Mary was not especially well off. She was partially dependent on her father, and he was very heavily dependent on debt. You can fairly argue that the ability to convince creditors to let you live on debt is a form of wealth, but the point remains that Mary often didn’t have the money to buy the art she liked herself. She had just enough money to have friends with money, and she was very successful in convincing them to spend it on the art she wanted. It’s a talent.

By the following year, in 1874, Degas was aware of Mary as well. He saw her painting Ida in the French Salon and said, “There is someone who feels like I do” (Hale, 55).

Now if this were a Disney movie, a Jane Austen novel, or daytime television, this electrifying vicarious introduction would be the beginning of a life-long romance or at least a brief torrid love affair.

But this was real life and Victorian real life at that. They certainly never married. There is no evidence of any romantic involvement between them. It is true that neither kept the letters they sent each other, and some historians have assumed that meant there was something to hide. But I doubt it. From all the surviving evidence, Mary was passionately devoted to Art, and only to Art. What she wanted from Degas was professional equality and respect. In Victorian times, a woman did not get that by sleeping around. And perhaps not much has changed.

Nevertheless, Degas was the man in Mary’s life. The same year that he first saw her work, he and Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, and several others staged their revolt from what they saw as the oppressive conservatism of the French Salon. They staged their own exhibition and vowed never to submit anything to the Salon again. They called themselves the Anonymous and Independent Cooperative Society of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers, which is certainly a mouthful. It proves that while they were visually brilliant, their verbal skills needed some work.

To their horror, this branding problem was solved not by a PR or a marketing firm, but by a critic. Louis Leroy wrote a scathing and satirical report of their first exhibition, in which he said among other things that when he got to Monet’s painting called “Impression. Sunrise”

he said to himself:

Impression — I was certain of it. I was just telling myself that, since I was impressed, there had to be some impression in it … and what freedom, what ease of workmanship! A preliminary drawing for a wallpaper pattern is more finished than this seascape.

-Louis Leroy, translated in Arthive

So Impressionists they became, and they were never able to live down the name. It just goes to show that as has been said before, the only way to achieve immortality as a critic is to say the wrong thing about the right people.

But Mary was not yet part of the right people. In 1875 the Salon rejected her painting The Young Bride because it was too bright. She should tone it down. In 1876, she toned it down and they accepted it, but she never forgave them.

In 1877 she met Degas in person, and he invited her to join the group that he was still trying to call the Independents. Mary said yes and never looked back. She later said of that meeting: “I had already recognized who were my true masters. I admired Manet, Courbet, and Degas. I hated conventional art. I began to live” (quoted in Hale, 56).

Becoming an Impressionist

In 1879 Mary contributed In the Loge to the fourth Impressionist Exhibition. It made her name as one of them. It is also an interesting commentary, though commentary of what is for you to decide.

The picture shows a well-dressed young lady in a box at a theater. She is looking through her opera glasses, and you could assume that she’s looking at the stage, because that’s why people come to the theater, right? Except her glasses aren’t tilted down to the stage. No, they are straight across, as if what really has her interest is someone sitting in the boxes opposite from her. Meanwhile one of the figures in the background is a man with his opera glasses clearly trained on her. In other words, no one’s really here for the play.

Meanwhile she and Degas were working in each other’s studios. She sometimes modeled for him. He did the background on one of hers. Each promoted the other’s work and offered critiques. Neither of them was famous for tact or gentleness, so it wasn’t always super kind, but it was always productive. It was not a student/teacher relationship, as has sometimes been reported. It was a true working partnership (Jones, xiv).

It was Degas who suggested a theme Mary would continue to explore for the rest of her life: that of maternity and children. It was a subject artists had done for centuries, but traditionally only religiously (Madonna and Child paintings were everywhere), and more recently, sometimes through portraiture (think Elisabeth Vigee le Brun), but what about other mothers? General mothers. Not portraits, but just paintings of motherhood.

Mothers and Children

In 1880 Mary did The Goodnight Hug. It’s not actually a painting, but a pastel drawing. It was the first of many works of mothers and children, and the question is why did she do so many.

The simplest answer is that she needed a way to distinguish herself from other impressionists. Degas did ballerinas and horses. Monet did water lilies and haystacks and cathedrals. Cassatt did mothers and children.

But there are other possible explanations. One interesting one is that painting small children was Mary’s only respectable access to doing a nude painting, which for so long was a required component of the serious art world (Broude, 39), and yet women were generally excluded from the classes on it. Many of Mary’s babies are nude (which not unusual in a world without disposable diapers). Everyone understood that, so no problem.

Another theory is that she did it to subvert criticism. She herself was not a shining example of Victorian womanhood. She was pursuing a career, not a family. But by making her career focus on the glory of woman’s role in the family, who could really complain? (Broude, 39)

Well, I’ll tell you who can complain: it’s the more modern feminists. They have criticized Mary for feeding into the feminine stereotypes at a time when large numbers of real mothers were abandoning their children to state-run orphanages because they could not feed them, at a time when sexual assault was common and mostly unpunished, at a time when women faced political, educational, financial, and professional discrimination at pretty much every level. Think Les Misérables here and the plight of Fantine, the unwed mother in poverty. That book had been written by this point, but the problems it pointed out were (and are) a long way from solved. What right had Mary, this feminist argument goes, to portray contented motherhood so smugly? To paint, as a reviewer in 1893 said, “only women with quiet souls”? (André Mellério, reproduced in Mathews, 202)

And then there’s the backlash to that argument: saying that Mary’s work was actually radically feminist, showing as it did, the actual work involved in caring for a child and valuing that work, for crying out loud (Pollock). Is it not the epitome of sexism to say that the work these middle-class women genuinely did do was not worthy of depiction?

As I say, plenty of contradictory impressions of Mary are here. And when seen in different lights, all of them may be true. The theory Mary herself most disliked was that only a woman could have painted these mothers and children (Hale, 150). And I have to say, I agree with her. If we are going to insist that women can paint as well as men, then we must also allow that men can paint as well as women. If men had never been mothers, well, neither had Mary. What they had been (and she was too) was a child with a mother. So yes, they could have explored this subject in paint. They just generally hadn’t bothered.

An Established Artist

Speaking of men and their paintings, things were becoming difficult with Degas. Their friendship floundered over politics. Also his misogyny. He made a comment that no woman could understand style. Mary painted Girl Arranging Her Hair to prove him wrong, and he was so impressed that he displayed it prominently in his own home; but still, the comment rankled (Jones, 13).

I myself am fully aware that I do not understand style, and especially I do not understand how this painting (as opposed to all the others) proves that Mary did, so if you know, get in touch, because I haven’t got a clue.

Mary, like many artists of the period, was deeply impressed by the flood of Japanese art that the West had only recently learned about. They were now looking at the startling effects of works like The Great Wave. All the Impressionists were affected. In Mary’s work, you can see it in some of her prints which, like Japanese ukiyo-e, feature large areas of flat color contrasted with decorative patterns on clothes, plus vibrant colors, simplified figures, and asymmetric compositions.

Those features are most obviously present in her 1894 painting The Boating Party, which shows the back of a man rowing while a woman and child sit on the far end of the boat.

It is at once very Mary Cassatt in subject matter and also a distinctly Japanese angle and orientation to choose.

After the mid-1880s Mary did less with Degas. But her reputation had grown elsewhere. In the 1890s she was commissioned to paint large murals for the women’s building at the Chicago World’s Fair, the very same fair and building that exhibited the young Uemura Shōen.

Mary accepted her World’s Fair commission with reluctance and much backsliding. Disputes over pay and whether America truly appreciated women artists, and other issues came and went. Her murals showed women pursuing knowledge, art, and fame, and they were a critical failure, by and large. Some people liked them, but in most reviews everything from her choice of color palette, to the height at which they were hung, to the very subject matter was criticized. Even a male friend of Mary’s asked her “Then this is woman apart from her relations to man?” as if he couldn’t quite grasp that concept. Yes, Mary said flatly. “Men, I have no doubt, are painted in all their vigour on the walls of the other buildings” at the Fair (Mathews, 187). And in this, she was quite right.

But at the same time, she did not want the murals to be thought of as women somehow adopting masculinity. No, she continued, “to us the sweetness of childhood, the charm of womanhood, if I have not conveyed some sense of that charm, in one word if I have not been absolutely feminine, then I have failed” (Mathews, 187). Sweetness and charm are not really words that some of the more brash feminists wanted to embrace. Hence the criticism from the other side of the women’s rights movement. Sometimes you just can’t win.

The Later Years

By the early 20th century, Mary had purchased a French chateau called Beaufresne where she grew over 1,000 roses. Sounds pretty rich, doesn’t it? And yet at least one of my sources assures me that chateau just meant substantial country house. Not really a castle. Still sounds rich to me, but I’m assured that she was not.

She was still painting, still drawing, but also doing a great deal of advising of collectors. It is because of her efforts that there are so many French Impressionists in the collection of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art (Pollock). In 1904, France granted her the Legion of Honor, which was pretty much proof that Impressionism was no longer fringe radicalism. But amid all these victories, a long life began to take its toll. She lost family members and was diagnosed with diabetes. She was treated with radium, which was not yet understood to be a poisonous (Hale, 244). Despite cataract surgery, she began to go blind.

In 1917, Degas died and despite their regular arguments and his own quite terrible health conditions, Mary wrote:

Degas died at midnight not knowing his state—his death is a great deliverance but I am sad . . . he was my oldest friend here, and the last great artist of the 19th century—I see no one here to replace him”

quoted in Jones, 19

In that last statement Mary was quite wrong, for Picasso had already come to Paris and had already painted some of his most famous work. But it is perhaps unsurprising that Mary, now in her 70s, failed to appreciate the next great revolution in art, just as the French Salon had failed to recognize hers. The Impressionists had succeeded so well they had become the establishment.

Mary died at her home in 1926. Today her work can be seen on the walls of museums all over the world.

Please add a comment below that tells me whether you think Mary was a rabid feminist or a panderer to all things oppressively Victorian. Should she even count as American? Or is she more French?

Selected Sources

Arthive. “Pictorial. Louis Leroy’s Scathing Review of the First Exhibition of the Impressionists.” Arthive, 16 Dec. 2019, arthive.com/publications/1812~Pictorial_Louis_Leroys_scathing_review_of_the_First_Exhibition_of_the_Impressionists.

Broude, Norma. “Mary Cassatt: Modern Woman or the Cult of True Womanhood?” Woman’s Art Journal 21, no. 2 (2000): 36–43. https://doi.org/10.2307/1358749.

Hale, Nancy. Mary Cassatt. Doubleday Books, 1975.

Hutton, John. “Picking Fruit: Mary Cassatt’s ‘Modern Woman’ and the Woman’s Building of 1893.” Feminist Studies 20, no. 2 (1994): 319–48. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178155.

Jones, Kimberly A, and Amanda T Zehnder. Degas Cassatt. Washington, National Gallery Of Art, 2014.

Mathews, Nancy Mowll. Cassatt, a Retrospective. New York, H.L. Levin Associates, 1996.

Pollock, Griselda. “The Overlooked Radicalism of Impressionist Mary Cassatt.” Frieze, 3 Sept. 2018, http://www.frieze.com/article/overlooked-radicalism-impressionist-mary-cassatt.

Regarding Style and Girl Arranging Her Hair— I feel like an answer is just on the tip of my brain. I blame great physical fatigue, which is also a thing of motherhood. I feel like @asta.darling on Instagram would have an answer.

LikeLike

[…] this series on Great Painters, we’ve had women who painted because they loved art, women who painted because it was the family business, women who painted because they needed money, […]

LikeLike

[…] contributions to the art world. From Artemisia Gentileschi‘s captivating narratives to Mary Cassatt‘s tender depictions of motherhood, and Frida Kahlo‘s unapologetic self-portraits, these […]

LikeLike