The current series is Great Painters, but the immediate question is: what is the next series topic? The poll for that is live on Patreon, and (small change to the system) it is available even if you have not and do not want to sign up as a subscriber. Please go out and vote your preference between (1) the history of girlhood, (2) the history of women’s protests, and (3) the history of female mummies (Egyptian, Danish, Inca, and more).

We have arrived at modern art. When my daughter was ages 3 to 6 we lived in a couple of different places in Europe. We traveled as much as is possible with a small child and a tight budget. We went to many of Europe’s greatest art museums, and at one point my small child turns to me and says in all seriousness, “What does modern art mean? Does it mean not good?”

Some of you might respond that she just said out loud what everyone else was thinking anyway. Nevertheless I am going to round out this series with four modern painters, all of them wildly different from each other, and I hope you will like at least one of them.

Hilma af Klint was born on October 26, 1862, in Stockholm, Sweden, to a family of naval officers and minor nobility. That means she is absolutely no relation to the Austrian Gustav Klimt who painted The Kiss (his name with an “m”, Hilma’s got an “n”).

The only thing in Hilma’s childhood home that approximated art was the collection of nautical charts. She was sent to school, which means she had parents who valued education. You can tell because they had to pay for it. The state only valued education for boys. That was what they offered free (Voss, 22-24).

Hilma was relatively privileged. She finished secondary school and took painting classes so she could be among the first women to enter the Stockholm Royal Academy of Art. Women were allowed, but they trained separately from the menfolk, and even so their presence was controversial. The complaints against them were strongly worded, but still boil down to the same intellectual level as saying girls have cooties.

When she wasn’t at art school, Hilma was attending séances. Yes, séances. In the modern world, many (but not all) people are inclined to smile at the idea of using a ouija board to speak to the dearly departed. But the spiritualist movement was completely serious in the late 19th to early 20th century. Mary Todd Lincoln held séances in the White House. Queen Victoria did the same in Buckingham Palace. Thomas Edison worked on a spirit phone that was supposed to call the dead (Zarelli). Arthur Conan Doyle wrote Sherlock Holmes stories, and he also wrote books on psychic research, declaring in one that though he had once thought that people who believed that stuff had a weak spot in the brain, “a man has to be very self-satisfied if the day does not come when he wonders if the weak spot is not in his own brain” (Doyle, chapter 1).

If people of their caliber said it was real, who was a teenage girl from Stockholm to argue? The first recorded direct message from spirits unknown to Hilma herself was:

“God be with you, my child! A clear light has come to your path. Do not let it be shadowed by the darkness of doubt, but wander happy and humble in its glow, thanking the Lord for his infinite love. Do not fear, even if you hear voices that want to frighten you, because of the light. These are the temptations that you must reject, for a child that believes never fears.”

quoted in Voss, 57

Séances were conducted in a group and meticulous notes were kept, but we have no record of Hilma’s response to this. But she did keep attending.

Her art at this time was entirely conventional. Her major piece in 1887-88 was a large painting of Andromeda at the Sea. Andromeda in Greek mythology was the princess whose parents angered Poseidon, so he sent a sea monster and Andromeda got chained to a rock to serve as tribute until Perseus showed up and rescued her and married her, and they lived happily ever after or something like that. Andromeda had been painted many times before, damsels in distress having a great appeal across the ages. The main things that set Hilma’s depiction apart are that she didn’t bother with painting the monster, and her Andromeda looks more contemplative than scared. It’s almost like she’s there to relax, because who wouldn’t be relaxed while sitting naked on a rock with manacles and a monster on the way?

Thus far, Hilma had taken a pretty passive role in the séances, but in 1891, she asked if she could try the psychograph, which was basically a ouija board as far as I can tell. The spirits beyond said to her to “Go calmly on your way.” Later that year after an accident with a horse drawn cart, the spirits gave her medical advice and said “Hilma will receive a great gift, if she never forgets the power of the highest” (Voss, 69-70).

By 1896, Hilma was into much more than just speaking to the dead. She joined the Edelweiss Society, which was certainly spiritualist, but also mystic. The leader, a woman named Huldine Beamish, believed she had direct access to the divine and also she believed in reincarnation. She herself had been St Catherine of Siena in a previous life. Also it was important to find your soulmate in life, but that soulmate was a spiritual union and need not be the same person you happened to be married to. Hers wasn’t.

The Edelweiss Society was a serious organization. They had an altar, a chapel, guestbook, rosters, and minutes of their meetings (Voss, 80-82). They were related, but not the same as the Theosophical Society. That one was founded by Helena Blavatsky, who had studied eastern mysticism and believed, among other things, that humans had once been pure spirits, but the material world had separated them from their spiritual selves, though they could respiritualize with work (Klint, 34).

One thing you may have noticed is that both these groups were led by women. And indeed, that was part of the appeal of spiritualism. The world of formally organized religion had little room for female leadership or innovation. But spiritualism was a realm in which women were celebrated. They were often seen as more sensitive than men (Klint, 8).

The formal art world was not much different than the formal religious world. Sure, they allowed Hilma to graduate and occasionally to exhibit in a small dark room separate from the main galleries reserved for male artists. But they didn’t really want her in the art world, and making it big was not really going to happen. Is it any wonder that she gravitated in another direction?

Her next group would be, not just founded by women, but exclusively women. In 1896, she and four other women became their own group which they called The Five. Hilma was not the leader, but she kept their notebooks, which contain pages and pages of messages from another realm, with no explanations. Some are verbal, some are nonrepresentational images. It wasn’t necessarily Hilma or any other trained artist who held the pencil.

Over time, certain spiritual voices became prominent. Gregor was an 11th century priest, who came frequently. Also Amaliel and Clemens. Later, one named Ananda which was interesting because the others were all legitimate Christian saints’ names. Ananda is Indian, a name associated with Buddha, and The Five weren’t sure how to spell it (Voss, 5).

Back in the material realm, Hilma lived with her mother and took commissions to illustrate textbooks on children’s books.

Her art world and her spiritual world were not very connected until she took a trip to Italy. Visiting the churches there, she could hardly fail to see how art is a gateway to the divine, and on her return a being named Esther said “Take the pencil Hilma” (Voss, 117).

In 1904, Ananda gave this message:

“Ananda also prays for you, Hilma. You should rest for days, quiet and still. Look toward images, old ones, images that wait for you. Just have patience, then you will be guided, calmly and surely, to the goal that lies before you.”

quoted in Voss, 124

It’s not a particularly unusual message when you compare it to the others in the notebooks, but for Hilma it was life changing. She would be guided to images. Her art world and her spirit world were now firmly connected.

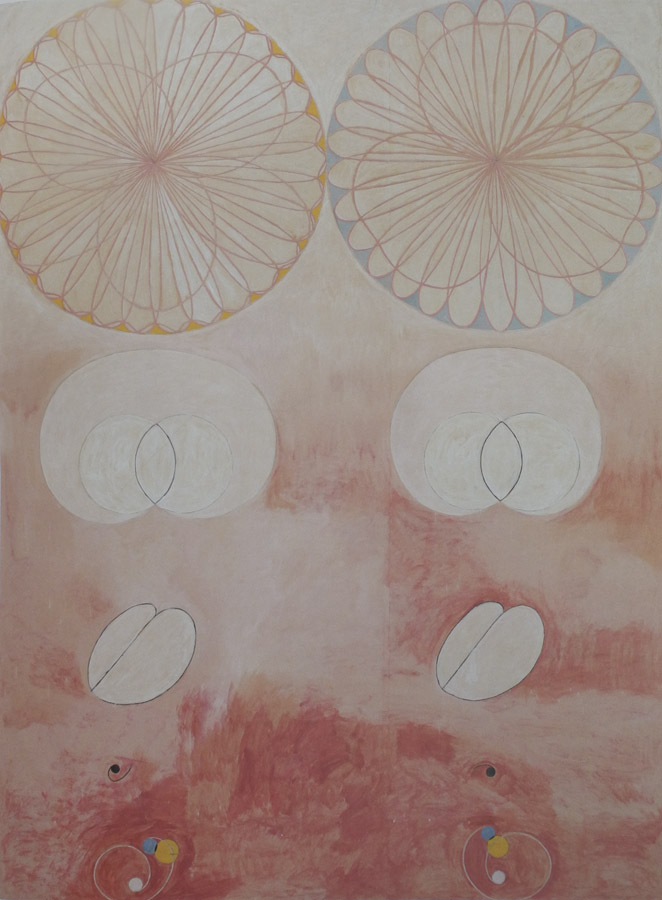

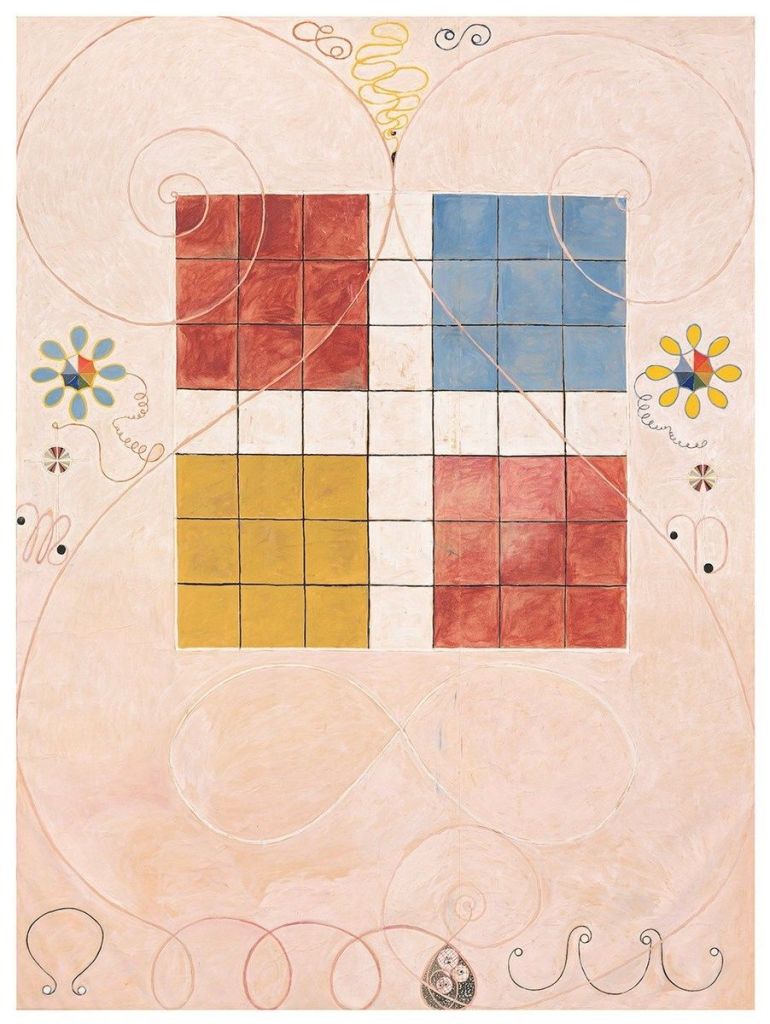

1904 is also the year that she formally joined the Theosophical Society, which by now had a lot of books, symbology, and doctrine. In particular, nature included seven planes, of which the physical world was the lowest. The astral world was the next step on the road to the spiritual. Any art coming from the astral world would have to be nonrepresentational because anything you could recognize as a physical object was still a depiction of the physical world, the lowest plane. Thus, abstract art was born. It was born as an attempt to rise above the world as we know it.

And the physical world was providing plenty of reasons to rise above, because revolution was breaking out in Russia. Old power structures were wobbling badly. Science was thriving, and though the formal religious world was sometimes appalled, science was not in any way at odds with spiritualism, for hadn’t Marie Curie just proved that there really are invisible forces of great power affecting us all the time? Hadn’t Darwin shown that lower beings could evolve into higher ones? Yes, I know a scientist could argue with that interpretation, but as far as the spiritualists were concerned, science was proving what they had believed all along. Let’s just not talk about what the nascent science of psychology had to say. That one was at odds with spiritualism.

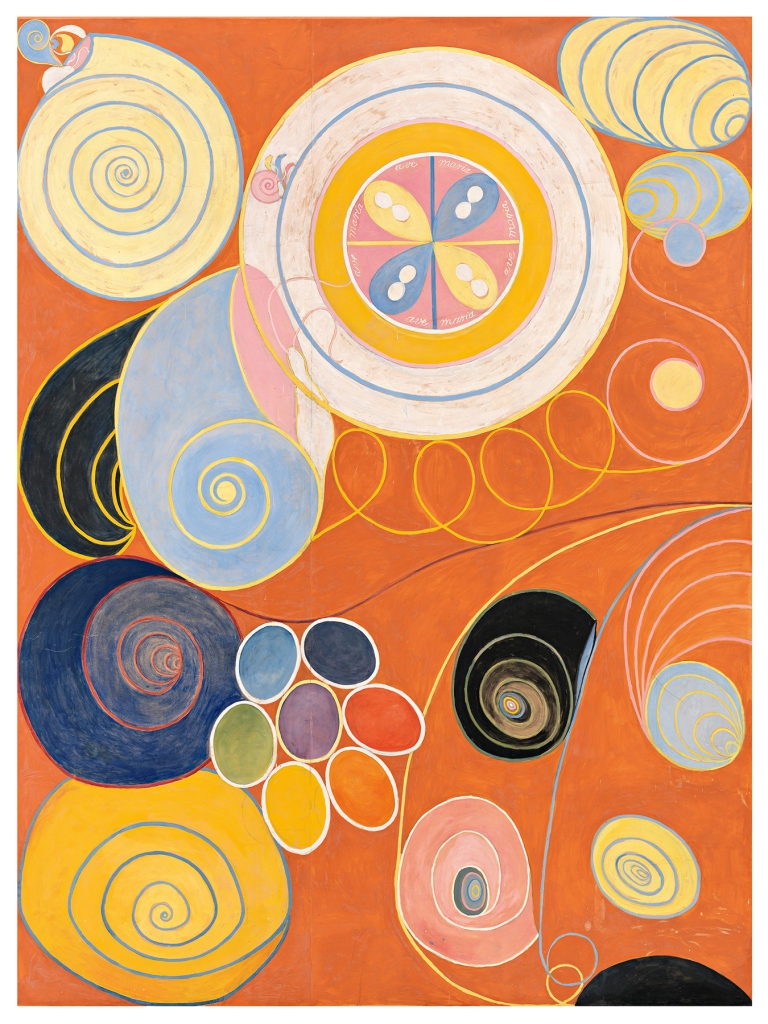

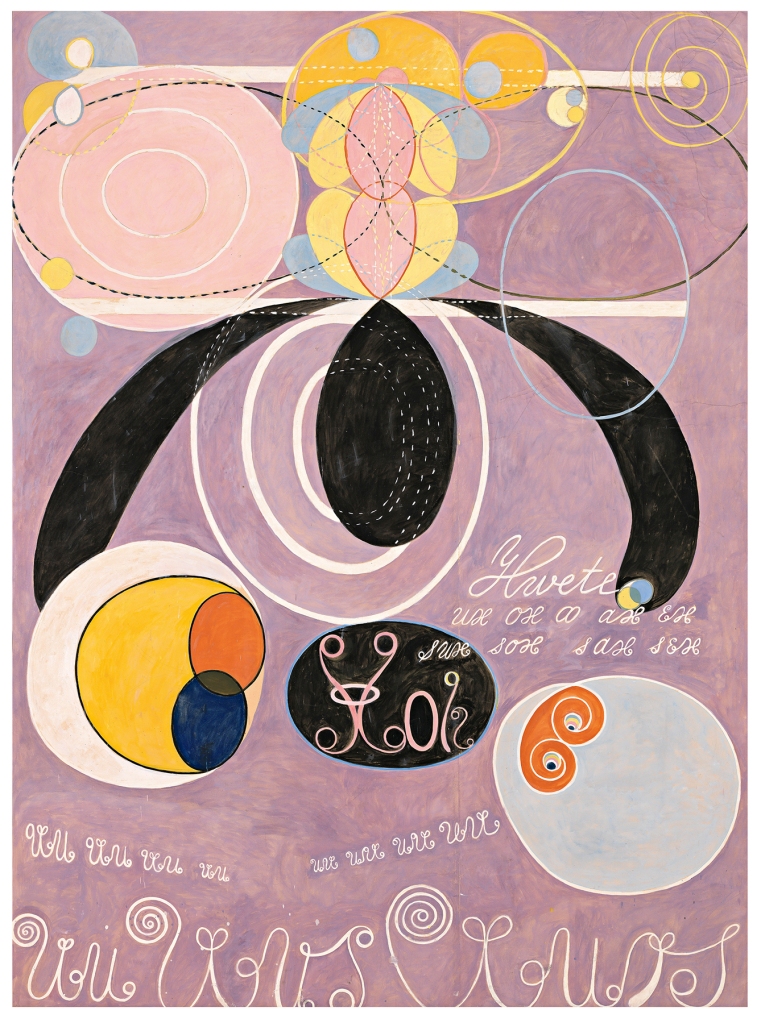

Hilma began painting a series called Primordial Chaos in 1906. These were mostly blue, yellow, and green. They featured spirals, lines, and occasional words and letters.

Hilmar was 44 years old and nothing like these paintings had ever been seen before. On the physical earth anyway. The astral world congratulated her, and their comments are recorded. The physical world continued to not see art like this, for the voices advised Hilmar that “As long as it is necessary, the paintings must remain hidden from the eyes of the general public, until the time to come forward is possible” (quoted in Voss, 138).

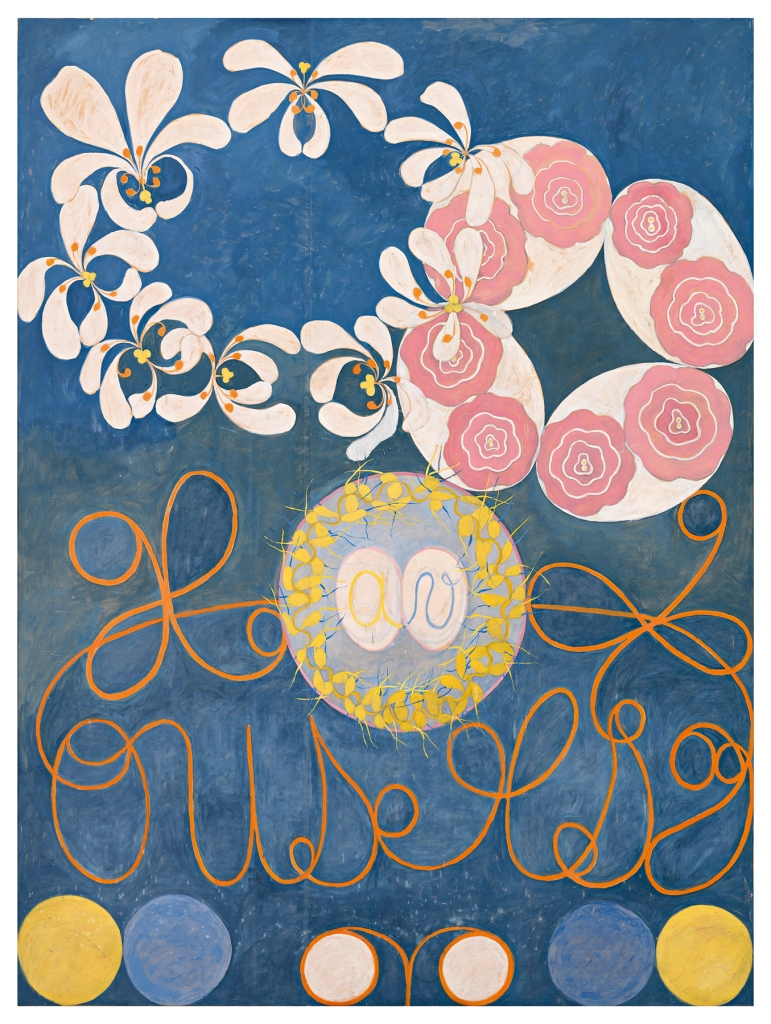

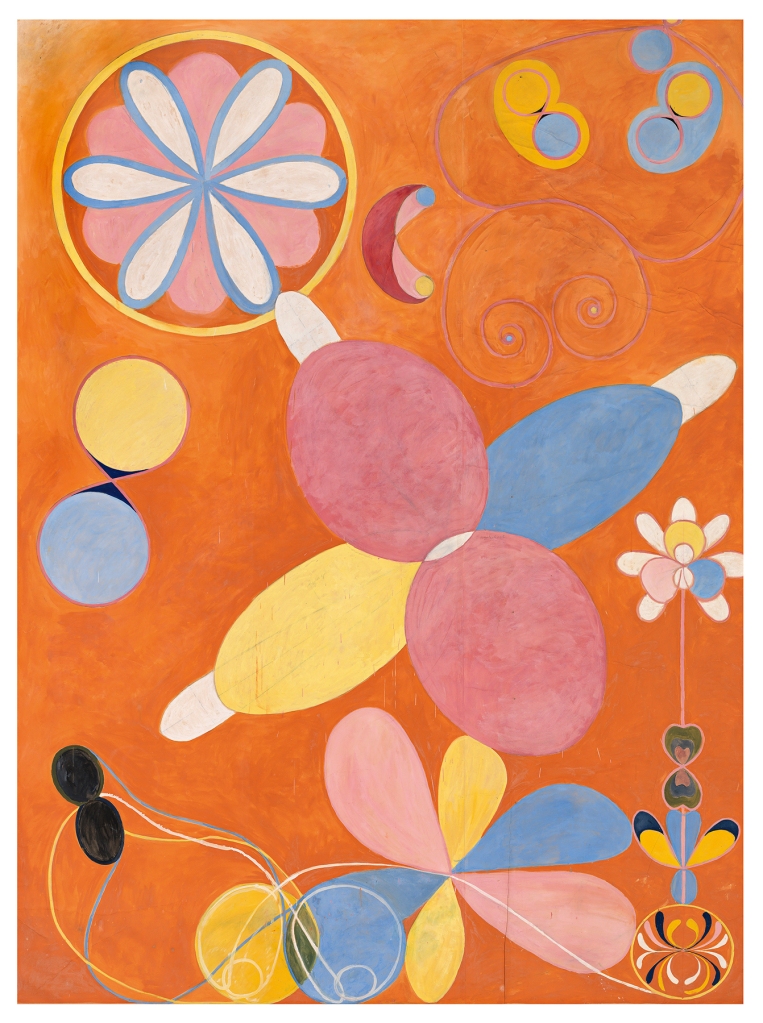

Primordial Chaos was quickly followed by a series called Eros, and then one called Large Figure Paintings, and then The Ten Largest. These last are all as big as barn doors and have many bright colors, swirls, and flower-looking things. They also have letter combinations like mwu, which Hilma recorded means faith. But other symbols seemed to confuse even her.

The spirits were not confused. They said ““You’ve now completed such glorious work that you would fall to your knees if you understood it” (quoted in Voss, 144).

It was good to have a spiritual fan club, because fans on earth were in short supply. The artists she shared a studio with declared her work “unsuitable” (Voss, 140). Rudolf Steiner, now the international leader of the Theosophists, looked at a few of her paintings on his visit to Sweden, but he refused to stick around long enough to have the kind of dialogue with her that she obviously wanted. Even The Five were dubious. They didn’t like how Hilma had seized control of their group.

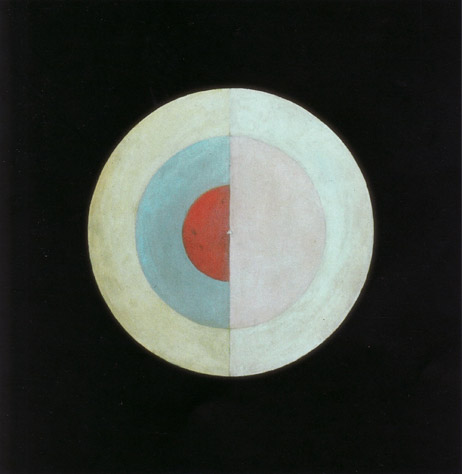

Undaunted, Hilma carried on. In 1914 she began a series called The Swan and the first painting in it actually looks like two swans, but each painting in the series becomes more and more abstract until by No. 17 it’s a set of colored circles. How the swan fits in, I don’t know.

Of course by this point, it was not just traditional art that was breaking. All of Europe was breaking. Sweden managed to stay neutral in World War I, but it was still affected. Among the refugees who fled to Stockholm was one Wassily Kandinsky. Also a spiritualist and also one who had used that spiritualism to create abstract art. He exhibited in Stockholm and the leading Swedish psychiatrist said that work like his was a clear sign of mental illness (Voss, 202).

Hilma either didn’t know or didn’t care. Her notebooks don’t mention Kandinsky’s presence at all.

Though she was still chasing commissions of traditional art to pay the bills, she was utterly absorbed in other worlds. As men died by the thousands across Europe, Hilma wrote 2,058 pages on “Studies of the Life of the Soul.”

Among other things she writes about womanman and manwoman and how misleading appearances are. “Many who fight in this drama are dressed in the wrong clothing. Many female costumes conceal a man. Many male costumes conceal a woman” (Voss, 212). Hilma did not believe that gender stayed the same through reincarnations. She herself had been a man before, and in her symbolic work she often assigned herself the masculine role.

It is impossible to read about this in the modern world without thinking about the LGBT movement. But while I think Hilma would have been very intrigued by modern developments there, I’m not clear on exactly how she would have fit herself into it. As far as I can tell, for example, she never attempted to change her name, her dress, or her pronouns. Certainly medical interventions were unavailable to her. But if she had lived later when these concepts were at least somewhat socially accepted, maybe she would have done such things. On the other hand, maybe her masculine qualities belonged purely in the spiritual world, not the physical. Maybe her desire for a masculine role was purely based on frustration with women’s status at the time. Or maybe not.

What is clear is that she lived and worked surrounded by women. One of them left brief journal entries that describe Hilma in frankly sexual terms (Voss, 189). But as far as I can tell, Hilma’s notebooks don’t leave anything like that (for either men or women), nor would I expect them too. Such things certainly existed, but relatively few wrote them down. Basically, I don’t know what labels she would have claimed, if claiming LGBT labels had been an option for her.

In the 1920s, Hilma tried to chase down Rudolf Steiner again. By now he had headquarters in Dornach, Switzerland, for a whole community of Theosophists. Hilma went several times. He barely made time to speak to her. He did have an impact on her though. On his advice, she got rid of hard lines in her next series. It is pure color (Voss, 232-235).

What Steiner did not offer to do was house her paintings. She was completely out of space and she wanted them seen by those who would appreciate them, preferably in Dornach, among Theosophists. She even offered to burn them if Steiner found them of no value (Voss, 239).

A Theosophist friend offered to exhibit them in Holland, which sounded promising, but it all fell through. Then in England, which did happen. This was at the World Conference on Spiritual Science in 1928. Reviews on the conference fail to mention Hilma’s presentation at all. Which is almost more disappointing than a negative review. She just wasn’t having any impact whatsoever (Voss, 250). She was extremely ignorable, and how much of that was a gender issue is hard to say.

On her return to Sweden, she clearly decided not to bother with the opinion of contemporaries. She began marking many of her works with a “+x” which meant they were not to be opened until 20 years after her death (Voss, 264).

In a way her timing was a shame, because it was only about this time that around the world in New York, an enthusiast named Hilla von Rebay was hard at work convincing the wealthy Solomon R. Guggenheim that he should be enthusiastic about modern art too.

Rebay’s thinking was very much on the same lines as Hilma’s. She was building not a museum, but a temple, and she wrote:

“For thousands of years astronomers, as well as laymen, believed that the earth was the center of the universe, around which all other planets revolved . . . For an even longer period of time there was a belief that the object in painting was the center around which art must move. Artists of the Twentieth Century have discovered that the object is just as far from being the center of art as the earth is from being the focal point of the universe.

Hilla von Rebay (quoted in Voss, 266)

Rebay liked Wassily Kandinsky’s work. The person who didn’t like it was Hitler. In Germany nonrepresentational art was declared degenerate and confiscated. Kandinsky was trying to reclaim a work of his from 1911 on the grounds that it was the very first abstract painting in the world. He had invented the genre.

That claim was flatly untrue. Hilma had been doing abstract art for years before that, and Kandinsky may have known it, through Rudolf Steiner. If he didn’t know about her, he definitely did know about several other painters like her. But he had grasped (as few others had) that the future of abstract art was in New York, and his claims played well there. He had also mostly dropped the spiritualist connection. That was not what most of the New York collectors were interested in (Voss, 289).

Hilma would never have dropped that spiritual connection. In the end, I think it’s safe to say she was more interested in spiritualism than she was in art. In 1943 a local admirer offered to build a museum to house her works and offered Hilma extremely generous terms.

Hilma said no. Why? Well, she was explicit in her final letter: “despite your interest in what I produced, you still didn’t understand its higher origins” (Voss, 298).

Artistic admiration was clearly not enough. One had to believe.

In 1944, Hilma fell off a streetcar and hurt herself. She never recovered. Her house and her life’s work were left to her nephew Erik, who was far too busy serving in the final stages of World War II to do anything about it. Everything was boxed up and placed in his attic for years.

Her obituary said she was a failed artist. After all, she had exhibited only occasionally and sold even less.

Years later when Erik tried to give her work to Swedish museums, they declined on the grounds that it was too derivative of Kandinsky. Despite the fact that some of it was older than Kandinsky (Voss, 304).

The first major exhibition of Hilma af Klint was in Los Angeles in 1986, and since then her fame has soared. When the Guggenheim in New York finally displayed them in 2018, they had more visitors for it than for any other exhibition in their history. They had to extend their hours to accommodate them all (Guggenheim).

The question is whether Hilma would have been pleased with achieving artistic acclaim at last. I don’t think the Guggenheim asked visitors whether they were believers in the astral world before admitting them.

Some of them quite clearly were not. The New York Times began its review with these words: “If you like to hallucinate but disdain the requisite stimulants, spend some time in the Guggenheim Museum’s staggering exhibition, ‘Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future’” (Smith).

I suspect Hilma would have been offended by the word hallucinate. But in a secular sense, the review was entirely positive. In episode 10.1 I referenced Linda Nochlin’s 1971 essay “Why have there been no great women artists?” According to the New York Times, Hilma’s disappearance and then reappearance on the art scene settles the question.

“There have been [great women artists], but their achievements reach us in circuitous ways because of the obstacles that plague artists generally, and women particularly. These reasons — so complex and individual — have to do with the nature of artistic ambition, the psychic and material needs that make fulfillment possible and the extent to which these needs are met by society. Some artists, in response, create their own citadels of rationales, systems and even delusions.

Roberta Smith

Please leave a comment on whether you think Hilma was delusional, gifted, inspired, or something else.

Selected Sources

Conan Doyle, Arthur . The New Revelation. Gutenberg, 1918, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1638/1638-h/1638-h.htm. Accessed 1 June 2023.

Guggenheim Museum. “Hilma Af Klint: Paintings for the Future Most-Visited Exhibition in Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s History.” The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation, 18 Apr. 2019, http://www.guggenheim.org/press-release/hilma-af-klint-paintings-for-the-future-most-visited-exhibition-in-solomon-r-guggenheim-museums-history.

Hilma af Klint Foundation. “About.” Hilma Af Klint Foundation, hilmaafklint.se/about-hilma-af-klint/.

Klint, Hilma af , et al. Hilma Af Klint : Notes and Methods. Chicago ; London, The University Of Chicago Press, 2018.

Smith, Roberta. ““Hilma Who?” No More.” The New York Times, 11 Oct. 2018, http://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/11/arts/design/hilma-af-klint-review-guggenheim.html.

Voss, Julia. Hilma Af Klint. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 27 Oct. 2022.

Zarrelli, Natalie. “Dial-a-Ghost on Thomas Edison’s Least Successful Invention: The Spirit Phone.” Atlas Obscura, 18 Oct. 2016, http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/dial-a-ghost-on-thomas-edisons-least-successful-invention-the-spirit-phone.

The feature image is Hilma’s undated self-portrait. (Wikimedia Commons)

Hilma af Klint’s journey as an abstract painter is fascinating. What does modern art mean to you? Did you ever question its significance? I’m intrigued by Hilma’s involvement in séances and the spiritualist movement. How do you think it influenced her art?

LikeLiked by 1 person

If I had the patience to remember whether I had a Patreon account, I would vote for Dry Bones.

LikeLike

Good to know! Dry Bones is currently the frontrunner, so you are in good company!

LikeLike

[…] business, women who painted because they needed money, a woman who painted for science, even a woman who painted because ancestral spirits told her to, but Frida is the only one who began painting because she was bored and in pain and she needed a […]

LikeLike

[…] in the White House, and Queen Victoria would hold them in Buckingham Palace, and as I described in episode 10.11, artist Hilma af Klint would hold them in Sweden. It all began here with the Fox […]

LikeLike