Dolls are the quintessential girl’s toy, but it turns out not all girls like playing with dolls. My own daughter certainly never had the faintest idea what you were supposed to do with a doll, and there are other pastimes. Dolls were murky last week, what with our inability to tell the difference between a child’s doll and an adult’s fertility symbol, and this week will be no clearer.

Games and pastimes mostly don’t get a mention in the records that are more concerned with the death of kings and the collection of taxes. If we manage to know about an ancient or medieval game at all, we usually have no idea who played it. Girls? Boys? Adults? Everyone? If you had no Netflix, Disney+, Hulu, YouTube, or podcasts (gasp), you can imagine that certain games would start to sound a lot more interesting. There is certainly no logical reason to think that only girls would enjoy them. For the pastimes I include today, I am by no means saying that boys and grownups didn’t play them. I am also not suggesting that girls didn’t play the so-called boys’ games. This is only an incomplete collection of pastimes that someone, somewhere, at some time, thought were associated with girls.

Knucklebones

First up is among the most ancient. It’s knucklebones, which you might know as jacks. In its modern incarnation, jacks are metal or plastic little knobbly things. The goal is to pick them up with one hand in between bounces of a little ball, without missing either the ball or the jacks. If you’re super coordinated, there are endless variations and tricks and fancy ways to do it. A version of this game has existed the world over in almost every civilization for millennia, but I don’t think the little knobbly things were made of plastic. Bone was more likely, being readily accessible (hence the name knucklebones), but small stones and seeds work too.

We have statues of Greek and Roman girls playing their version of the game dating from at least 300 BCE (British Museum). There’s also a frieze of girls playing at Pompeii.

The Japanese version is called otedama. It dates from at least the 9th century and is still played by Japanese girls today. It is done with nine small silk bags of rice, one of which is a different color. That one corresponds to the ball in the jacks game I am more familiar with. Sure, a little bag of rice doesn’t bounce, but if you’re good, in that version, it’s not intended to hit the ground at all (Craig, 66).

You can also see girls playing knucklebones in a gorgeous painting done in 1560 by Flemish painter Bruegel the Elder.

This one is definitely worth a good long look at, for there is nothing else like it in the history of art. It’s called Children’s Games, and it is a composite picture of over 200 children playing over 80 different games. It looks like one of those super busy pictures in children’s magazines where you’re supposed to hunt to find the hidden items. Or Waldo. Only it’s from 1560! And yep, in the bottom left, you can see girls (not boys) playing knucklebones.

Hopscotch

Speaking of games of dexterity played with readily available equipment, there is also hopscotch. Again there is no earthly reason why this game should have any gender qualifications at all, and some of the origin theories are not in favor of girls. And yet the association with girls is there, at least in some parts of the world. There are, again, worldwide versions of this game, but basically it involves drawing a sequence of squares on the ground, marking some of them as forbidden, and then hopping through the squares on one foot, not landing in the forbidden square, but retrieving the marker as you go by.

We know this game is ancient because no less a figure than Buddha included it on a list of games that are a total and complete waste of your valuable time (The Book of the Discipline, 382). Buddha’s dire warnings did not stop children in India from scratching their squares in the mud two and a half millennia later (Narasimhan, 346). Or schoolgirls in Australia playing it in the 19th century (Howard, 167). Or the daughters of rival factions in Ireland in the 1920s (O’ Donovan).

Exactly how to play the game varies in each location. But perhaps most interesting variation I came across was observed in girls from Los Alamos, New Mexico, in the 1940s. If you are unaware, Los Alamos is a remote location where the US government developed the world’s first nuclear weapons. In the 40s, Los Alamos girls were the daughters of people brought in to work on the project. And some of these people must have talked about their jobs at home because Los Alamos girls were labeling their forbidden squares in hopscotch as “contaminated” (Thorpe, 385-6).

Jump Rope

Let’s move on to jump rope. This one seems equally obvious. All you need is some rope-like thing, which most cultures definitely had, and yet jump rope does not seem as ubiquitous as knucklebones and hopscotch. There are many websites eager to tell me that jumprope was invented by the Chinese, or Australian Aboriginal people, or the Phoenicians, or the Egyptians, but what all of these websites had in common was the total lack of any actual sources. Bruegel didn’t paint any children with a jump rope, and given the complexity of his painting, surely that means it wasn’t a common children’s game at his time, either for girls or boys?

What I can say is that by 1800, jump ropes existed, and girls were jumping them. In that year, a print seller in England published a pinup picture of a lady doing so. Admittedly, the character depicted was fictional, but art follows life, right? Or if not, then the other way around in short order.

By 1833, jump rope was included in a book called The Girl’s Own Book by Mrs Lydia Maria Child. Here’s what Child had to say on the subject of jumping rope:

This play should likewise be used with caution. It is a healthy exercise and tends to make the form graceful; but it should be used with moderation. I have known instances of blood vessels burst by young ladies who in a silly attempt to jump a certain number of hundred times, have persevered in jumping after their strength was exhausted.

There are several ways of jumping a rope

-Lydia Child in A Girl’s Own Book, from 1833 (p. 103-104)

- Simply springing and passing the rope under the feet with rapidity.

- Crossing arms at the moment of throwing the rope.

- Passing the rope under the feet of two or three, who jump at once, standing close, and laying hands on each other’s shoulders.

- The rope held by two little girls, one at each end, and thrown over a third, who jumps in the middle

You may notice the Child says nothing about chanting or singing along with the jumping. As far as I can tell, those were added later, though some of the rhymes already existed. They were folk songs and rhymes co-opted for the purpose of jump rope (Opie, 129), and they vary considerably around the world.

Running

What takes even less equipment than knucklebones, hopscotch, or jump rope is a footrace. At least it took less equipment in the days before fancy footwear. Culturally, we tend to think of such contests as being for boys, and in many times and places that is a perfectly accurate assessment. But not in all.

In ancient Greece, the Olympics were just for men. In fact, women weren’t welcome even as spectators. But they could attend the Heraea, named for the Queen of Heaven, Hera. There was only one event, and it was foot racing. There were three age divisions, and no one bothered to record the ages, but my source on this guesses they spanned ages 6 to 18. If you won, you got the same olive wreath crown as the men and a share of the sacrificial ox (Scanlon, 32).

Obviously, most of us girls have never brought home Olympic gold, but your average Greek girls were running at home, partly because it’s fun, and partly because the girls with actual talent needed someone to leave in the dust. That definitely would have been my role. For all that Sparta has a bad rep in the literature, that’s really only because most the literature was written by their enemies in Athens. If you were an athletically inclined girl, Sparta was the place to be. Girls there were allowed to compete in all the events, not just foot racing (Scanlon, 33).

Twirling

For the youngest girls, there is a physical game so trivial that I can find no written mention of it anywhere. But surely all of us remember twirling, spinning around as fast as we could until we collapsed, completely dizzy. On this one, I think there it a logical reason to connect it to girls rather than boys. Because it’s one of the very few physical activities that really is more fun in a dress. Which is not to say that boys never wore dresses. (We’ll be talking more about that in a couple of weeks.) But girls wore them more. And sure enough in Bruegel’s painting, in the top left corner you see girls twirling and their dresses spinning out. So fun.

Dress Up

For those of us who are not athletically inclined, there are entertainments of the imagination. It includes dolls, which was last week, but you don’t have to have a doll to play. Sometimes you are the doll, with dress up of your own. I have found exactly zero references to kids in the ancient world dressing up, but I am 100% positive they did. Yes, cloth was expensive and nobody was wasting it like we do now, but you don’t actually need cloth to dress up. And I have proof: in Bruegel’s painting just above the girls playing knucklebones is another girl. She’s got on her a cone-shaped hat, but surely it was not the latest fashion because and it’s made out of twigs. Nothing expensive needed. She probably made it herself.

In the slightly more recent past, I did find a written reference. In 1842, a ten-year-old Louisa May Alcott wrote somewhat ungrammatically in her diary that “I ran in the wind and played be a horse, and had a lovely time in the woods with Anna and Lizzie. We were fairies, and made gowns and paper wings. I ‘flied’ the highest” (quoted in Brewster, 170).

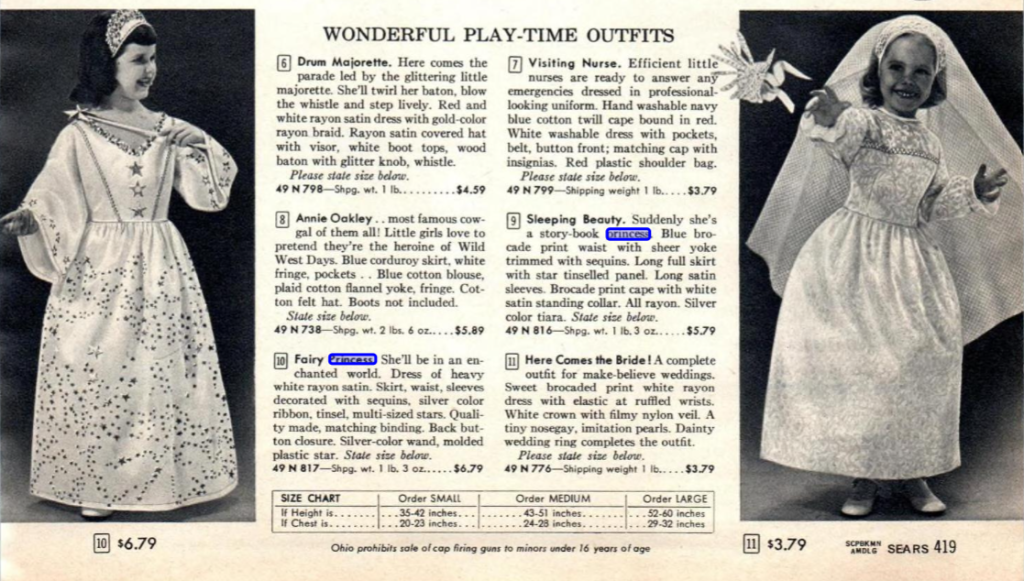

There is one interesting tidbit about dress-up that I noticed while perusing the 1937 Sears Roebuck Christmas Wishbook. They had dress-up clothes for sale, but every single one of them was intended for boys: cowboy suits, lawmen, and one airplane flight lieutenant (Sears, 1937, 34). There was not a single princess dress to be seen.

But then again, the Sears employees who put the 1937 catalog together hadn’t yet seen Walt Disney’s Snow White, which came out four days before Christmas that very same year. What a missed opportunity! I thought for sure that was going to be rectified the very next year, but I was wrong. Even five years later in 1942, the Christmas catalog had no princesses, and almost all the dress-up clothes were for boys. Girls could choose between two: the Wild West outfits now included one for a Broncho Girl, complete with pistol and lariat. Those made sense. What did not make sense was that the skirt and vest were made of imitation leopard skin, leading me to be somewhat concerned that the designer actually knew where the wild west was. There were certainly mountain lions out there, but leopards? (Sears, 1942, 113). A girl’s other dress up choice in 1942 speaks to the reality of the world in 1942. For $2.15 you could get a 58-piece little Army Doctor Jim and Nurse Sally kit, complete with professional looking outfit and

“everything a young doctor needs!” You very much get the sense in the copy that the marketers weren’t sure which gender would be buying this. But they hasten to add “sets like these are heartily encouraged by famous child psychologists because they encourage imagination” (1942, 94). I’m sure the girls didn’t care what the psychologists thought.

Not until the 50s did Sears get on the dress-up clothes parade for girls. Then girls could order outfits to be a drum majorette, a visiting nurse, Annie Oakley, Sleeping Beauty, a fairy princess, or a bride (Sears, 1950-59, 1172).

Play Kitchens

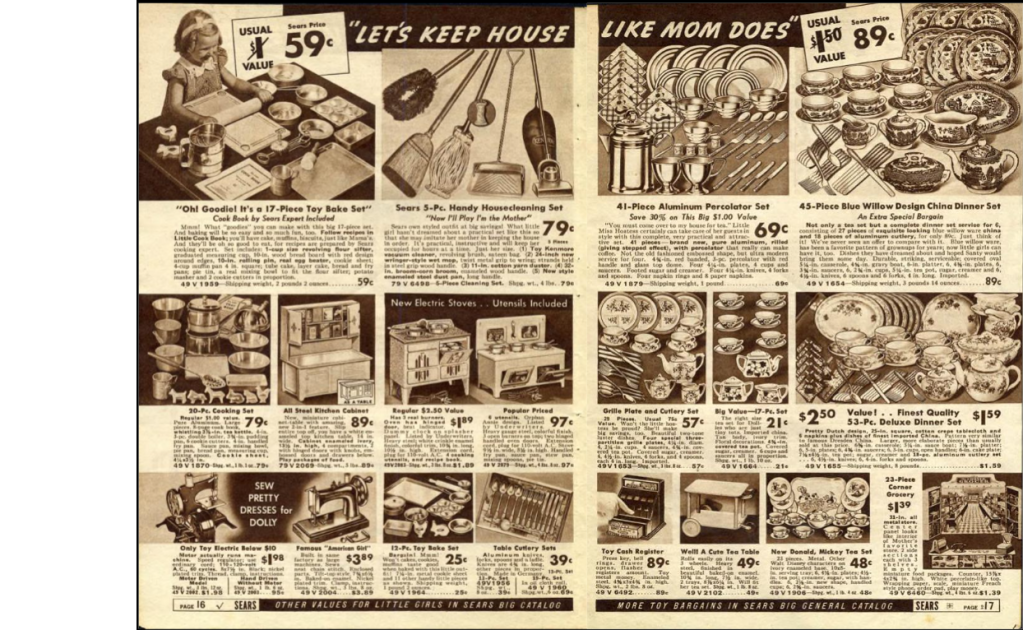

Whether you have a costume or not, you can play at being a grown-up woman if you have a toy kitchen. If you are a very lucky girl, one will be provided for you. In the distant past these were provided, custom-made, to rich children from Japan (Shikibu, 218) to the American colonies (Mintz, 85).

I have not been able to track down when the first commercial versions were made, but they were certainly in full swing by the time of that 1937 Sears Roebuck Christmas catalog. It has a 2-page spread labeled “Let’s Keep House Like Mom Does.” Twenty-five cents for a 12-piece toy bake set, and let your eyes (and your wallets) just get bigger, right on up to the 53-piece finest quality deluxe imitation Dresden china dinner set of plates, cups, platters, silverware, and more, a $2.50 value for only $1.59, an absolute steal (Sears Catalog, 1937, 16-17).

I had thought of toy kitchens. Thats why I looked it up. But there on the same page, was something I did not think of: 79 cents and for a 5-pc Handy Housecleaning Set with a mini vacuum cleaner, mop, duster, broom, and dustpan. Because—and I’m quoting here—“What little girl hasn’t dreamed about a practical set like this so that she may imitate her mother in keeping the house in order?” (Sears Catalog, 1937, 16-17). I don’t know how practical girls in the 30s were, but all I’m saying is, I hope the girls who woke up to that on Christmas morning never saw the catalog with the 53-piece imitation china set. It’s just so much more exciting.

The fact that such luxuries were unavailable to most girls of previous eras (and even most girls of that era) did not prevent them from acting out their dreams of adulthood. In the 1950s, girls in the Philippines were observed assembled their own cooking sets out of castoff bits of broken pottery, and they even seemed to prefer them to the very few manufactured cooking sets in their community because those were expensive so the adults were always telling them to be careful. Nobody cared how they treated the self-assembled sets (Whiting, 836). I have a source on those Filippino girls, but surely girls around the world had been doing the same for millennia. Front and center of Bruegel’s painting are a group of girls pretending to be in a wedding procession. All of it done with self-assembled props the adults had cast off.

And in the bottom right, another girl is playing at running a shop of art materials (and yes, Dutch women of the period did that, see episode 10.4 on Judith Leyster).

Handicrafts

There is an entirely different class of entertainment for children that we now call crafts, and there are very marked gender differences here. Now you might say that sewing is not a game or an entertainment or a pastime for a historical girl, and if you’re talking about plain sewing, you are exactly right. Plain sewing was work: tedious, arduous work and a necessary life skill for girls in almost every social class. There is little room for creativity, innovation, or fun in hemming a sheet or making a shirt out of the only fabric you can afford. It’s a rare girl that found it fun.

But some of the similar skills were fun. Lydia Child moves in and out of work and amusement in her chapter on handicrafts. She first stresses the supreme importance of being able to make a shirt perfectly by the age of 12, which means that some of us are a bit behind schedule. I am firmly in the remedial class here. But she particularly mentions beadwork as fun. In other cases, her suggestion is to make something practical, like a pincushion, but it’s mingled with fun, for she suggests making them in an amusing shape, such as a cat, or an easy chair, or a harp, or a fish. Speaking honestly, I could do with a little more instruction than she gives because even after reading the chapter I haven’t got the foggiest idea how to make a pincushion in the shape of an easy chair, but the point is that many girls have always enjoyed crafts, and crafts with a needle are the most universal across the cultures and millennia for girls.

There are three major categories of needlecrafts that I will note specifically because some girls and women still do them. For fun. And yet I was very surprised by what Lydia had to say about them. I mean there was paragraph after paragraph about pincushions in fun shapes, plus fifteen types of basket making, even more types of paper crafts, and several where she suggests using lead acetate (which is toxic) and nitric acid (which is highly corrosive), but when she got to embroidery, she said “This is nearly out of fashion, and I am glad it is: for it is a sad waste of time” (224). Okay, I sniff, eyeing my latest embroidery project.

And then there’s quilting and she says, “this is old-fashioned too; and I must allow it is very silly to tear up large pieces of cloth for the sake of sewing them together again. But little girls often have a great many small bits of cloth, and large remnants of time, which they don’t know what to do with, and I think it is better for them to make cradle quilts for their dolls, or their baby brothers than to be standing around, wishing they had something to do” (225). And I’ve also purchased cloth specially for the purpose of being cut up into smaller bits of cloth, so silly of me, but I did.

And finally, there is knitting, where Lydia really takes the cake by coming out in its favor. “This favorite employment of our grandmothers ought not to be forgotten,” she says. And Why not? Well, because “it enables one to be useful in the decline of life” (226). I am not a knitter but I know quite a few women who are, including many who are most definitely not in the decline of life, so I am still personally offended here, but I think the lesson is that regardless of age, someone has always been ready to criticize how you spend your time. Personally, I’d steer girls toward the knitting and away from the lead poisoning, but maybe that’s just me.

Bicycles

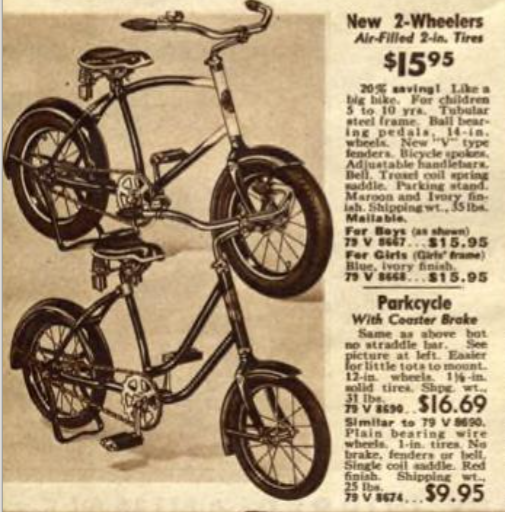

One pastime that Lydia Child did not even mention was bicycling, and it was not because they didn’t exist yet. Bikes had been invented sixteen years earlier in 1817 in Germany, and they were not for kids or women. The evolution of the bicycle is worthy of its own episode in a different series, because it had very profound implications, especially for women. However, with regard to girls, it didn’t come into its own until after World War I. By then, many adults had abandoned it in favor of a car, but kids didn’t have that option. In the minds of Americans, it moved from the category of serious transportation to child’s toy, an attitude that serious cyclists find seriously annoying. But that’s history for you. In 1933, the Schwinn company released a new style of bicycle with balloon type tires, and while six of the models were intended for boys. The seventh was intended for girls (Sweeney). In 1937, Sears was selling bikes specifically for girls as young as 3-years-old (Sears, 1937, 28).

The rise of the bicycle was just one example of the opening up of formerly male pastimes to girls and women. Tennis, hockey, soccer (or football for you non-Americans), all of these would become more and more available to girls throughout the 20th century. Which is quite interesting given that the toys were becoming more gendered.

I will be talking about how girls got pink and the boys got blue in a couple of weeks in an episode about clothes, but for now let’s just say that this is a very recent idea, historically speaking. Those bikes I mentioned in the 1937 Sears catalog? The one for boys was maroon. The one for girls was—wait for it—blue. Yes, blue. The girls-must-have-pink concept just wasn’t there yet. For marketers, the concept was brilliant because now parents had to buy two of each toy if they had both a boy and a girl (Liffreing). They tried this even with toys that had always been gendered. One toy train company put out locomotives in pink, thinking girls would buy it. It didn’t work. The girls who liked trains wanted trains that looked like trains (which are not pink). The girls who didn’t care about trains didn’t want them in any color, not even pink (Babione).

he argument between those who like pink and those who don’t was only one of the hotly contested debates about toys that sprang up in the late 20th century. There was also a lot of agonizing about whether gendered toys were bad for girls generally. If they only play at being princesses, does that mean princess is the only career they are fit for? Maybe if we encouraged them to play with blocks and little doctor sets they would grow up to be engineers and surgeons instead of disappointed beauty queens.

A lot of toy companies rushed to fill the void of STEM toys for girls. But their efforts are as hotly contested as the originals. If it’s the same toy as the boys got, only made pink, have we really progressed anywhere? If it’s a slightly different toy then the boys got, then why and how is it different? The prime example of this came from Lego. Legos had always appealed to boys. They wanted to reach girls. Their market research suggested that boys played with Legos by building things, but girls played with Legos by developing storylines and relationships. Therefore, they came out with the Lego friends, marketed for girls, and they are very much less like building toys and very much more like traditional dolls and doll houses. Again, have we really progressed anywhere? All of that agonizing was present even before the question of gender-neutral toys for transgender children became a hot topic in the public forum.

I don’t have the perfect answers to any of that, but I’ll just say again, that regardless of age, someone has always been ready to criticize how you spend your time. I suggest: just play with whatever you want. Especially if it’s knucklebones, which really is fun.

Selected Sources

Babione, Carly. “Lionel Girls Train Set: The Little Enginette That Couldn’t | Skinner Inc.” Bonhams Skinner, 16 Feb. 2017, http://www.skinnerinc.com/news/blog/lionel-girls-train-set-2981t/. Accessed 25 Sept. 2023.

Brewster, Todd. American Childhood. Simon and Schuster, 23 May 2023.

Child, Lydia Maria . The Girl’s Own Book. Clark Austin & Co., 1833, books.googleusercontent.com/books/content?req=AKW5QadXtkhCdKFUB4ID-EHh0_Ni1aweHGYmhzjnZeF2A8sUbJp7RNjrYFmpWMciryvEeKEWeIOyAUtYr2LDfozplFN8dlD5oDao677HHvTQSkJKTW45RHsv9pe3KxrvWPgmqWqnnqViFCY1Y5eIapCdB_r6ICTcwmXhcXNZoCu3FIWfnnzm3ZYXI_y9b6j00L4lLrJhkaWPMwGcmOkn9UuGmnO-3RJ6kOjI7pagxt-1twMTJsbVopN3wkunqr3Ojs-M8VOizX73. Accessed 21 Sept. 2023.

Howard, Dorothy. “Australian ‘Hoppy’ (Hopscotch).” Western Folklore 17, no. 3 (1958): 163–75. https://doi.org/10.2307/1496040.

Liffreing, Ilyse. “Millennial Pink: A Timeline for the Color That Refuses to Fade.” Digiday, 31 July 2017, digiday.com/marketing/millennial-pink-timeline-color-refuses-fade/. Accessed 25 Sept. 2023.

Murasaki Shikibu. The Tale of Genji. Translated by Arthur Waley, http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/66057/pg66057-images.html. Accessed 14 Sept. 2023.

Narasimhan, Raji. “Ration Office.” Indian Literature 23, no. 3/4 (1980): 344–49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23328971.

O’Donovan, Danielle. “SMALL LIVES: AT HOME IN CORK IN 1920.” History Ireland 29, no. 1 (2021): 8–9. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27198114.

Peck, Sandra. “Using Oral Evidence with Infants: A Toys and Games Project for 5-7 Year Olds.” Oral History 20, no. 1 (1992): 41–45. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40179254.

Scanlon, Thomas F. “GAMES FOR GIRLS.” Archaeology 49, no. 4 (1996): 32–33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41771026.

—. The Tale of Genji. Translated by Arthur Waley, http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/66057/pg66057-images.html. Accessed 14 Sept. 2023.

Sears Roebuck. 1937 Sears Christmas Wishbook Catalog. 1937, archive.org/details/1937-sears-christmas-wishbook-catalog/page/n33/mode/2up?view=theater. Accessed 22 Sept. 2023.

—. 1942 Sears Christmas Wishbook Catalog. 1942, archive.org/details/1942-sears-christmas-wishbook-catalog/page/94/mode/2up. Accessed 22 Sept. 2023.

—. 1950-1959 Sears Wishbook Toys. 1959, archive.org/details/1950-1959-sears-wishbook-toys/page/n1/mode/2up. Accessed 22 Sept. 2023.

Sweeney, Shawn, and Gary Meneghin. “The First American Balloon Tire Bicycles -.” Vintageamericanbicycles.com, vintageamericanbicycles.com/index.php/the-first-american-balloon-tire-bicycles/. Accessed 24 Sept. 2023.

The Book of the Discipline (VINAYA-PIṬAKA). Translated by I.B. Horner, Oxford University Press, 1938, americanmonk.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/1.-I.B.Horner-Vol-I-Suttavibhanga.pdf. Accessed 21 Sept. 2023.

Whiting, Beatrice B. Six Cultures: Studies of Child Rearing. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1964.

[…] All of the early magazines were dominated by moral lessons and sentimental verses (Bingham, Abadie, 4). There were some moderately successful ones, like the Juvenile Miscellany, run by Lydia Maria Child, who we met in episode 11.5. […]

LikeLike