If you are a modern parent you may well have had the experience of collecting so many baby clothes that your baby grew out of them before she even had a chance to wear them. Really, babies grow so fast, and people are so eager to give you the most adorable things. It can be an overabundance.

Historical mothers largely did not have this problem. Partly because cloth was expensive—oh so unbelievably expensive—but also because cute baby clothes as we know them were not a concept. What would the point of all those little flowers or princesses, when you are just going to cover it all up with a swaddling blanket?

The question of to swaddle or not to swaddle would eventually reach a fever pitch, but for most of human history, there was no question. You just swaddle. For those of you who may be hazy on what that even means, to swaddle is to wrap the baby up tightly in a blanket or long strips of cloth, so that only their cherubic little face pokes out. It looks uber-ultra-uncomfortable to us because it is basically a straightjacket: you are tying those little limbs down so that they can’t move.

As unbelievable as it may sound, many (but not all) babies like it. Perhaps it reminds them of the womb. Anyway, I can personally attest that my angelic neighbor Becca who gave me a special swaddling blanket when my daughter was born pretty much saved my life because my daughter could not sleep without it, which means I could not sleep without it.

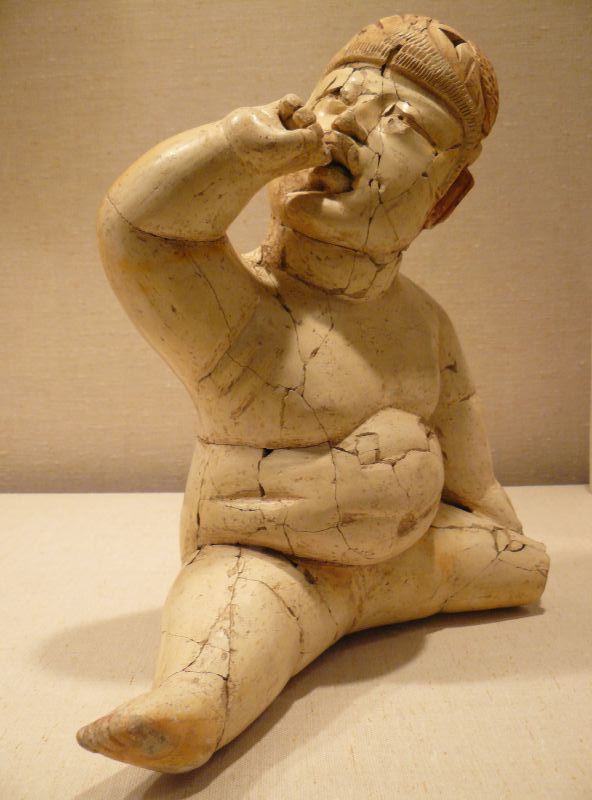

The most famous person to be swaddled is none other than Jesus Christ himself. That’s Luke 2:7. But he is not the only one. We have painted or carved depictions of swaddled babies from Crete (2000-2600 BCE), from Greece (5th century BCE), from China (2nd-3rd century CE), from upper class Europe (medieval through 17th century), from North American native people of multiple tribes (across several centuries), I could go on.

To the extent that there are written records, they confirm that swaddling is just what you do. Our friend Soranus, the Roman gynecologist from episode 11.1, states it explicitly: “one must swaddle the new born with wool specifically” and he goes into detail about how. For girls you’ve got to bind the breasts tightly but keep the loins loose. Boys you can just keep at even tightness all the way around. Oh and I forgot to mention that you need to salt the baby before doing this. It sounds ever so slightly like rubbing a spice blend on a side of beef, but I think the point was to have a drying agent in there, because believe me, things are going to get moist (Soranus, 83-85). These swaddling bands are taking the place of cute baby clothes and blankets and diapers.

Fifteen centuries later English midwife Jane Sharp still assumed a baby would be swaddled, though she has little in the way of instructions. Basically, she just says be gentle “for infants are tender twigs, and as you use them, so they will grow straight or crooked” (Sharp, 372).

After the Swaddling

Exactly when you are going to stop swaddling your baby is a mystery. Instructions range from a few weeks to a few years. (I find that last one hard to picture, but that’s what it says.) But whenever it happens that’s the point at which you need children’s clothes, right?

Well, not necessarily. If you live in a hospitable climate, the simplest thing to do is to leave children in the nude. It’s cheaper, it cuts down on laundry, and they can’t possibly mistreat their clothes if they haven’t got any. We have artistic evidence of that from ancient Egypt and the Olmec in Meso-America.

Obviously it doesn’t work so well in some other climates. But that still doesn’t mean that those peoples would understand what you meant by children’s clothes. For most of history, children’s clothes were quite literally smaller versions of adult clothes, whether that be a tunic, a chiton, a kimono, a robe, or a dress. Nothing like the onesie or any other child-specific item existed, so far as we know.

Admittedly, what we know is not a lot. Clothing mostly doesn’t last that long, archaeologically speaking, and the people most interested in children’s clothes (by which I mean the children who wore them and the women who made them) were mostly illiterate. There’s not much in the record, so most of what we have to go on is from art history.

Even there we have a problem, because as I discussed in episode 11.2, there just aren’t that many artistic depictions of children until the 17th century, and then they were still mostly in Europe. And when they do get going, you just have to feel sorry for those sweet little kids, stuffed into the most ridiculously uncomfortable clothes. Like the 5-year-old Margarita Teresa, who in Velazquez’s 1656 portrait has hips pretty much as wide as her arm span.

By age nine they are considerably wider than her arm span. Just imagine trying to play jump rope or hopscotch in that dress.

Or there’s 2-year-old Claude Francoise of Lorraine. She’s dressed as a nun—or at least it looks like a nun’s outfit to me. All black, except for the white wimple and a rosary at her belt.

It’s a little more comfortable-looking than Margarita Teresa’s, but nothing like as freeing as the thing worn by the Greek bronze running girl. She basically has a sleeveless, knee-length dress. You can imagine a girl of today in it except for one thing: it only has one shoulder strap and the neck line leaves one breast completely exposed. Apparently, she didn’t need a sports bra to go running.

Margarita Teresa and Claude Francoise were both upper-class girls in their finest, so maybe that’s not what they wore every day? The peasant girls in Bruegel the Elder’s 1560 painting Children’s Games are not so fancy, but they are still wearing long-sleeved, floor-length dresses, with aprons and bonnets.

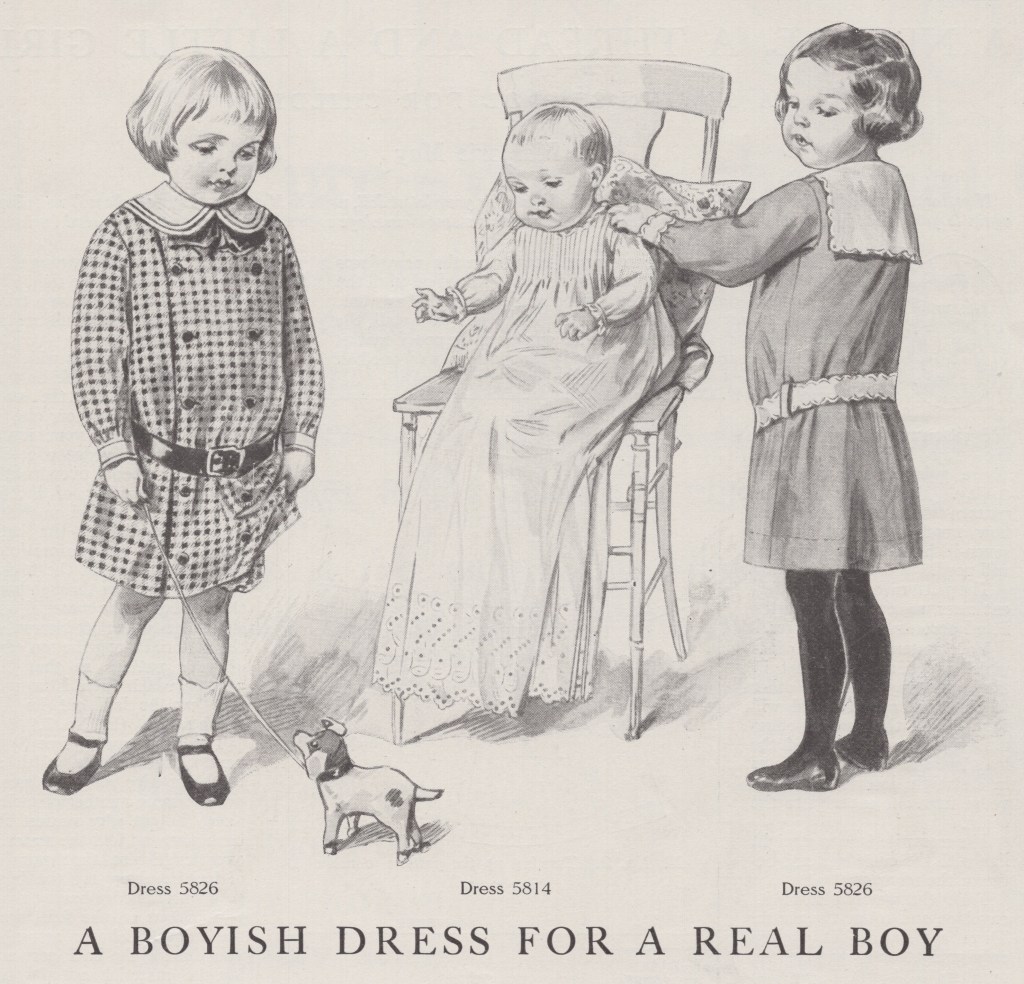

In all of these examples, the clothes are not a clue that these pictures are of children. We see the equivalent clothes on portraits of adults. As discussed in episode 11.2, the Discovery of Childhood, the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries saw a large increase in the number of European parents bothering to get portraits of their children and to a modern eye, it looks like they did this for their daughters and forgot about their sons. That would be a nice twist on the usual way of the world, but it is not true. It only looks that way because when kids got out of the gender-neutral swaddling clothes, they went straight into gender-neutral dresses. Yes, dresses for both boys and girls.

In the following two portraits by Dutch painter Paulus Moreelse (1571- 1638). Both are of toddlers in white dresses. Both have very fetching bonnets and gold jewelry and lace. One of them is a girl. One’s a boy. My guess is you won’t be able to tell which one is which.

(See the end of this post for the answer to which portrait is of a girl. Wikimedia Commons)

Little boys wore dresses until somewhere between ages 4 and 7, when they were “breeched”, which meant they were now grown up enough to wear pants, trousers, whatever you want to call them (Callahan). These were, by now, firmly associated with the male sex, and to hear more on why, you’ll have to go all the way, way, way back to episode 1.1, Who Wears the Pants Around Here. Little girls stuck with the dresses for the rest of their lives.

But changes were afoot. The same folks who were changing notions of childhood generally also had strong opinions on clothes. Especially about swaddling. Despite the fact that it had been done for millennia, Rousseau says bluntly that “Where children are swaddled, the country swarms with the hump-backed, the lame, the bow-legged, the rickety, and every kind of deformity. We make our children helpless lest they should hurt themselves. Is not such a cruel bondage certain to affect both health and temper? Their first feeling is one of pain and suffering … their first treatment, torture. Their voice alone is free. Why should they not raise it in complaint?… if you were swaddled, you would cry louder still.” (Rousseau, Book 1).

No doubt I would cry, but I’m not a baby, fresh from the womb.

Rousseau, as you can tell, was a master of the mom guilt trip, and I’ve only quoted a small portion of what he has to say. As I mentioned a few weeks ago, he said all this from a lofty position of never ever having stayed up all night with a colicky infant (swaddled or no) because he dropped his own children off at an orphanage rather than take the trouble to educate them.

But hands-on experience is apparently not necessary for writing a bestseller, and Rousseau was a best-selling author. So when he said that children should be dressed in loose, flowing frocks which allow freedom of movement, “with nothing tight, nothing fitting close to the body, no belts of any kind” (Book 2), that is exactly what began to happen, starting with the upper classes, who could read Rousseau, and then gradually moving across other classes of society.

If you aren’t going to swaddle and you don’t live in a climate or a culture conducive to child nudity, then suddenly you need baby clothes. The layette became a European and North American term for what you need to have on hand for your newborn, with the word “need” being in heavy quotes here, since undoubtedly a great many babies did not get all of it. Many women sewed their own layette, but commercially available sets began as early as the 18th century. Even borrowable sets were available for some women because honestly you’re not going to need it for that long. The kids grow fast. In some communities, women passed around a layette box of clothes to whoever was the newest mom at the moment (Buck, 45).

The exact contents of the layette varied, of course, but there was certainly no need to get the pink version versus the blue version. Even as late as 1927, the Butterick sewing pattern company (which is still in business today) made no distinction between boys and girls when listing the essential components of a layette, which were:

- 3 dresses

- 3 nightgowns

- 3 petticoats

- 3 bibs

- 3 kimonos

- 3 sacks

- 3 knitted shirts

- 3 knitted bands

- 3 flannel bands

- 3 pairs of bootees

- 24 diapers (these are cloth diapers, mind you, at 18×18 inches)

- 6 quilted pads (11×16 inches)

- 1 coat, and

- 1 cap (Butterick, 229)

Butterick is very, very clear on the fact that the big items are always white. Just white. You are permitted use pink and blue for bootees and blankets, but not for the dresses, caps, coats, etc. White was and had been the standard color for babies for a long time by then. Sounds like a terrible idea to my spoiled notions of laundry, but the logic was that white items can be bleached.

Butterick does not mention how long those three dresses were, and that is a change from previous times. In the preceding centuries, babies who were either just out of swaddling or never swaddled wore very, very long dresses. Like even down to the floor as they were being held in the arms of an adult. These long dresses were replaced with short ones when crawling or walking became a possibility. “Short-coating” was something of an event, a milestone to be noted, just as later generations would exclaim over first tooth or the first word (Buck, 59). Baby books of the 1910s still had a space to commemorate the date at which a baby first wore short dresses, but by the 1920s, the long dresses were a thing of the past (Callahan). Their only real survival is in the form of christening dresses, which are sometimes still quite long.

Around the same time (early 1900s), both boys and girls began wearing one-piece rompers, also called creepers or creeping aprons (Paoletti, 49). They are basically the antecedents of today’s onesies or body suits, the kind with legs. Which means that pants were acceptable for baby girls well before dresses for baby boys were out. Also, the rompers weren’t generally white. Which is how you can tell that synthetic dyes and washing machines have arrived. Rompers came in checked gingham or with animal or floral prints (Callahan), and they were specifically advocated for girls by a pediatrician as early as 1895 (Paoletti, 49) because it would allow them better movement.

Older Girls

For older girls, we need to jump back a bit. By the nineteenth century, girls’ clothes were distinguished from women’s clothing by two things: partly they were looser (not always a lot looser, judging by the fashion plates, but some looser). Girls still wore corsets. They just weren’t pulled that tight. Boys who had not yet been breeched were still wearing the same thing.

The other distinguishing feature of girls’ clothing vs. womens’ was length. Starting in the 1820s, girls were allowed to show their lower leg (Buck, 118).

Just kidding. They were allowed to show the stockings or pantalettes that covered the lower leg. There is a beautiful little diagram available on the Internet showing how long a Victorian girls’ skirts should be. At 4 years, knee-length. It allows movement. At 8 years, 2 inches lower, At 10 years, 2 inches still lower, until ankle-length at 16.

I was disappointed to have my illusions about the origin of this diagram shattered. Supposedly it’s from Harper’s Bazar in 1868. I perused the entire 1868 volume and there was nary such a diagram, but it did provide plenty of evidence that girls had much shorter skirts than their fashionable mothers. And in thinking about it, it’s hard to imagine how a diagram like that could possibly have had much relationship to reality. Girls grow. Clothes do not. Keeping up the precision of that diagram would have been a challenge.

The older a girl got, the more likely she was to have a full-length dress. And another sign that the wee girl is growing up was the doffing of the pinafore. Pinafores were for girls, not for women (Buck, 236).

Up until this point, most of our evidence is from portraits (which is to say rich children) or fashion plates (which is more aspiration than reality, as any woman larger than size zero knows). You can well imagine that a great many girls were wearing whatever they could scrimp for. In the 1890s though, we have a list of recommended wardrobe items for girls ages 12-15 leaving orphanages to enter domestic service. Again, this is aspirational. But at least it’s aspirational for the poor, instead of aspirational for the rich. A girl who definitely should have been in school, but was actually headed out to work crushing hours was recommended to have:

- 1 black serge dress

- 1 black cashmere dress

- 2 lilac print dresses

- 4 white aprons of yosomite (Google and I don’t know what that is)

- 4 linen aprons

- 2 hessian aprons

- 1 black jacket

- 1 waterproof cloak

- 1 sailor hat trimmed with ribbons

- 1 large black straw hat trimmed with silk or velvet

- 2 pairs gloves

- 1 umbrella

- 1 silk square for neck

- 1 pair of walking boots, levant and laced

- 2 pairs of houseboots, cashmere

- 6 pocket handkerchiefs

- 6 white linen collars

- 3 pairs of linen cuffs, and

- 4 caps (Buck, 230).

Lest you wonder what was going on underneath all this, that’s a separate list:

- 3 chemises

- 3 pairs drawers

- 3 calico nightgowns

- 2 red flannel petticoats

- 2 petticoat bodices in grey twill calico

- 1 corset

- 3 pairs black stockings, and

- 1 dark serge petticoat (Buck, 239).

I do really wonder why the flannel petticoats had to be red. However, I can say with certainty that the list itself, aspirational as it is, is proof that the price of cloth had plummeted. I guarantee that the equivalently poor girls of a few centuries earlier did not have such a long list.

Gender Distinctions in Children’s Clothes

The urge to have any gender distinction in children’s clothes was partly a reaction against a former woman featured in this podcast. Frances Hodgson Burnett is today best known for writing the beautiful book The Secret Garden, but during her lifetime she was best known for the sappy and sentimental Little Lord Fauntleroy. Some women dream about the perfect man. Burnett dreamed about the perfect son, and her vision of the boy was all the rage, at least among mothers. The look created in the stage play version was so popular—among mothers—that a whole generation of boys were stuffed into suits of black velvet, wide lace collars, and long, curly locks of luscious of hair. Adorable, thought the mothers. Sissified, thought some of the men. Little Lord Fauntleroy was a sensation in both North America and Europe.

Then Freud came along and cast mother-son relationships into a whole new light, and suddenly it became very, very important that boys be taught to be manly and heterosexual, right from the getgo, nothing effeminate going on here, thank you very much (Paoletti, 67-73). If we needed fictional role models for boys, they were going to come from the likes of Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer. Not Little Lord Fauntleroy. Basically, our boys need to prove their masculinity.

Obviously change is not overnight, but lace, ruffles, bows, and trims phased out of clothes for boys. Dresses, too, were worn less and less by boys. By the 1940s it was generally perfectly clear to everyone what gender a two-year-old was, which had definitely not been the case before (Paoletti, 83). But it mostly wasn’t the girl’s experience that was changing.

Pink Is for Girls

The gender distinction still wasn’t necessarily because of pink. Actually, pink as a word for a color only dates to the 1840s (Paoletti, 86). Before then pink was just one of many shades of red. And as I’ve said, most baby clothes were white. The trimmings might have color, but the colors had no consistent pattern except maybe about hair. Blondes supposedly looked good in blue. Brown hair went with pink. Gender was irrelevant (Paoletti, 87-88).

In 1918, an article appeared in a Chicago publication that said the question of gender and color was disputed, but most people thought pink better for boys because it was a stronger color. Blue was delicate, dainty, and feminine (Paoletti, 85, 90). The local department stores agreed, but it seemed to be regional. In Manhattan and Los Angeles, the color preference was reversed (Paoletti, 91) and that was just in the US. Throughout the world, many other customs prevailed.

There is no clear timeline or reason for why the Manhattan opinion prevailed over the Chicago one in the United States. It was just a gradual increase of pink for girls, blue for boys over decades. Right up until the 1960s when we suddenly didn’t want to emphasize gender after all. The unisex era runs from 1965-1985. Feminists were loudly rejecting pink for their daughters, which shows you just how far the culture had traveled in only a few short decades. Ironically it was the feminists themselves who linked pink so strongly with girls. It had never been fully cemented before they began arguing against it. Dark and contrasting colors were preferred to pastels and in the mid-1970s, Sears Roebuck catalog did not even sell any pink clothes for toddlers. Interestingly, unisex clothing in the 70s meant girls could wear traditionally boy’s clothes (whether they be blue, brown, or bifurcated). What it did not mean was that boys could wear girl’s clothes. The pink, the lace, the ruffles, they weren’t coming back for boys.

It was not until the 1980s that pink came back with a vengeance, and its gender associations firmly entrenched. But what about all those rabid, gender-equal-child-raising feminists? Didn’t they complain? Well, yes they did, but there are several theories about why their complaints no longer mattered. Possibly the clothing choices of the 70s were always more about a fleeting fashion preference than a hard-core principle, and the feminists had never been as successful as they gave themselves credit for. Or maybe they had succeeded in stressing women’s equality so well that parents no longer thought pink was a barrier to their daughter’s equal access to opportunity. Or maybe the girls themselves wanted pink and finally made their preferences clear. Maybe all of the above. By the early 2000s, pink was so ubiquitous for girls’ clothes that it was hard to find things even in colors like purple or turquoise, which in the 80s and 90s were definitely girls’ colors.

In the 2000s, there has been some small reclaiming of pink by boys and men. But if the Barbie movie is anything to go by, the association with girls and women is still very, very strong, and it seems unlikely to change. Meanwhile, girls are still allowed to wear boys’ clothes. It’s the boys who seem limited by the need to emphasize their masculinity.

Your Clothes Are High-Tech

I have a few final dates clothing-related dates for you to ponder because clothes are far more scientifically technical than you probably appreciate. Disposable diapers were not invented until the mid-20th century, so before that cloth ones, but even the safety pin wasn’t invented until 1849. Before that, ties or straight pins. Ouch. Snaps weren’t invented until the late 1800s. Elastic was not common until around 1900. Zippers not until the 1930s. Velcro not until well after the 1950s. Even buttons, which don’t seem all that high-tech were not common until well into the medieval period. Waterproofing for your outer layers was available for centuries as long as you happened to be an Amazonian with your tribe’s own rubber trees. For everyone else, that wasn’t an option until mid, to late, to really really late 19th century. None of this is unique to girls, of course, nor even to children, but imagine how very much more complicated it was for a girl to dress herself without these things. Imagine dressing yourself without these things. Just something to think about.

*In the Paulus Moreelse paintings above, the boy is the first portrait, and the girl is second.

Selected Sources

Borst, Jennifer. “Swaddling: Forever Bound in Controversy? – Hektoen International.” Hektoen International – an Online Medical Humanities Journal, 30 Apr. 2019, hekint.org/2019/04/30/swaddling-forever-bound-in-controversy/#:~:text=Swaddling%20has%20been%20practiced%20for.

Buck, Anne. Clothes and the Child. Holmes & Meier, 1996, archive.org/details/clotheschildhand0000buck/page/270/mode/2up. Accessed 17 Oct. 2023.

Butterick, The Art of Dressmaking. United States: Butterick Publishing Company, 1927. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Art_of_Dressmaking/eY1BAQAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0. Accessed October 17, 2023

Callahan, Colleen R. “History of Children’s Clothing.” LoveToKnow, http://www.lovetoknow.com/parenting/kids/history-childrens-clothing.

Chisholm, James S. Navajo Infancy. Routledge, 5 July 2017.

Gregoor, Ilse. “Researching Historical Children’s Wear.” Ilse Gregoor Costume Design, 13 Oct. 2018, http://www.ilsegregoorcostumes.com/researching-historical-childrens-wear/.

Paoletti, Jo B. Pink and Blue : Telling the Boys from the Girls in America. Bloomington, Indiana University Press, Cop, 2012.

Plato. Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vols. 10 & 11 translated by R.G. Bury. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1967 & 1968. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0166%3Abook%3D7%3Apage%3D789

Sharp, Mrs. Jane. The Midwives Book, or the Whole Art of Midwifry Discovered. Directing Childbearing Women How to Behave Themselves in Their Conception, Breeding … And Nursing of Children, Etc. [with Plates.]. London, Simon Miller, 1671, name.umdl.umich.edu/A93039.0001.001. Accessed 29 July 2023.

Soranus, Of Ephesus, and Owsei Temkin. Soranus’ Gynecology. Baltimore Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1994, archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.547535/page/233/mode/2up. Accessed 1 Aug. 2023.

Yep. This is consistent with what I have learned.

When I began bearing children. I wanted yellow and green and orange baby things because I consider them gender-neutral colors and could then use said things for all future children, no matter the gender.

Stuff being stuff, there was still some blue and pink mixed in there.

I have had many interesting conversations with people about their opinions upon specific colors that are NOT blue and pink. I have known many people who consider green and yellow and orange to be girl colors or boy colors. And I’ve met many strangers who call my blue-clad boy a girl. Does it bother me? Not enough to say anything.

-Katw the Great

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree with you that yellow, green, and orange are gender neutral, and I’m surprised that others don’t. Did they think those colors were for girls or boys? Or did they disagree with each other?

LikeLike

I remember some older guy on the bus told me that he thought orange was for girls. And I remember someone else told me that green was definitely for boys only. And even if I had my boy dressed in all blue, some people still used the female pronoun.

Lesson of the day: dress your baby in whatever color you want. Your baby us your accessory. Your baby is a hard thing to take care of, so you deserve that right until that baby can choose for themselves.

-Kate the Great

LikeLike

Testing the comment feature

LikeLike

Another test

LikeLike

Hmmm. I shall test as well.

LikeLike

[…] was that both body and soul would grow to be misshapen if left to themselves. That is why children, both boys and girls, were put in corsets when very small. Like age two. Otherwise they’d grow up to be deformed (Steele, 12; Bruna, […]

LikeLike

Re why the poor girls’ petticoats were red.

Red was considered a warming colour, so for years people had winter petticoats in red for warmth. (!)

Mary Queen of Scots wore red petticoats, so it goes back that far at least, and continued to the early 20th century.

It was probably also a practical colour for petticoats worn closest to the skin, especially in days before knickers were worn.

LikeLike

I didn’t know that. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLike