The underlying question behind educating girls is: Why? Why are you educating them? Throughout history, there have been varying answers to that question, and each answer has produced a wildly different strategies on how to do it.

For most of human history, a girl’s education consisted of hanging around older people, copying what they did, helping as instructed, until she got the hang of it. It’s simple, it’s cheap, and it’s effective at teaching the practical, physical skills of life.

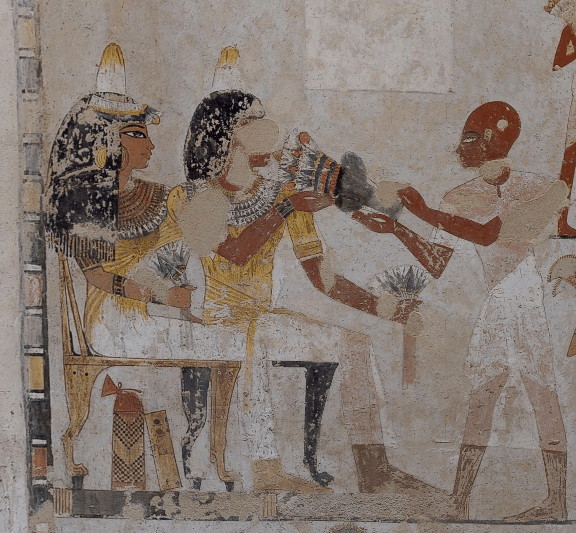

There clearly were some girls in the ancient world who got a more formal education, but we know this only by the results. There is the occasional literate woman, from Enheduanna in ancient Sumer, to Henutawwy of 19th dynasty Egypt (Taylor), to Sappho the Greek poet, to Hortensia of Rome. But how exactly these women became literate is a mystery. The general assumption is that they were probably home schooled by parents or hired tutors, and all of those people probably had a different answer to the question of “why.”

I am not a home schooler myself, but I know many families who are, and they all appear to be doing a fine job. They also all appear to be making heavy use of things like the Internet, and published curriculums, and the local library, none of which was available for home schoolers in the past. Even such high tech items as paper and pencil were scarce. Just imagine trying to do it without any of those resources!

Of course, most of the boys weren’t getting formal education either, but they got it more than girls did. We know that partly because of results (loads more male writers than female ones), but also because of the very occasional writer saying Hey, that’s not fair.

Ancient Calls for Girls’ Education

As far as I’m aware, the first such writer to complain was Plato (427-348 BCE). Plato argued that “we shall not have one education for men and another for women, especially as the nature to be wrought upon is the same in both cases” (Kersey, 8).

But Plato’s argument didn’t catch on. In the next generation, Menander the comic dramatist wrote that “he who teaches a woman letters feeds more poison to the frightful asp” (Clabaugh, 167). The evidence suggests Menander was taken more seriously than Plato.

Over on the other side of Eurasia, things weren’t any different. There certainly is the occasional literate woman, one of whom was Ban Zhao, who in the 1st century CE wrote a treatise called Lessons for Women. In it, she pleaded, “it is the rule to begin to teach children to read at the age of eight years, and by the age of fifteen years they ought then to be ready for cultural training. Only why should it not be that girls’ education as well as boys’ be according to this principle?” (Zhao)

A worthy question, but again, it didn’t change the general trend.

St Jerome and the Education of Girls

The first glimmer I’ve got into how girls were educated comes from St Jerome (340-420 CE). Jerome was famous in his own lifetime for converting wealthy Roman women to Christianity. Indeed a number of Roman men were quite annoyed at the number of women Jerome led into celibate vows, but that’s just a side note.

Jerome wrote many letters to his female fans. One woman named Laeta wrote to ask how to educate her daughter Paula, and here’s a portion of what Jerome wrote back:

“Have a set of letters made for her, of boxwood or of ivory, and tell her their names. Let her play with them, making play a road to learning . . . and remember their names in a simple song, but also frequently upset their order and mix the last letters with the middle ones, the middle with the first. Thus she will know them all by sight as well as by sound. When she begins with uncertain hand to use the pen, have the letters marked on the tablet so that her writing may follow their outlines… Offer prizes for spelling… You must not scold her if she is somewhat slow; praise is the best sharpener of wits… Above all take care not to make her lessons distasteful; a childish dislike often lasts longer than childhood.”

St Jerome, quoted in Classics in the Education of Girls and Women by Shirley Nelson Kersey, p. 12-13

I’m sort of amazed at how modern-sounding some of this advice is. Later on, Paula was to learn the scriptures in Greek and Latin, singing (but not musical instruments, dear me, no), but yes to spinning and needlework (Kersey, 13-14).

Jerome’s ideas would form the basic curriculum for Christian girls into the 18th century (Kersey, 10), which you gotta admit is pretty good longevity for any idea. Little Paula grew up to become the head of a nunnery, which for a non-royal woman was about as high as it was possible to go (Kersey, 11).

The Medieval World

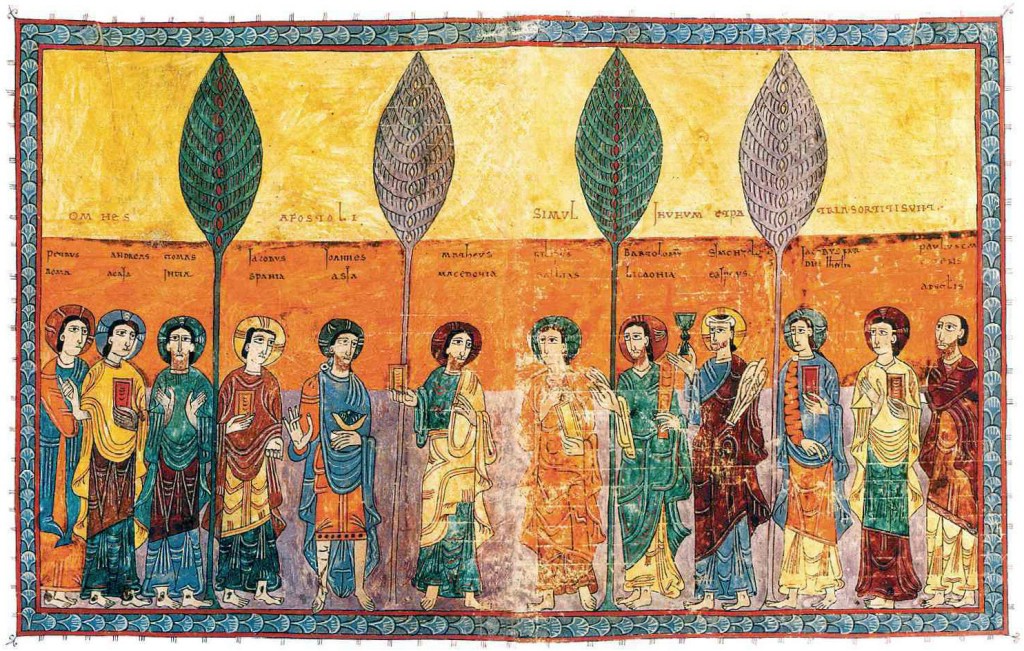

After Jerome we are back to silence on the subject for a few hundred years. In 746 Pope Gregory declared that educating the masses was a duty of the clergy (Kamm, 3). He very specifically included women in that, but he meant religious education, which doesn’t necessarily require literacy. At any rate, the answer to the “why” question was because education made women better able to serve God and church.

The medieval period had some nunneries where girls were taught to read, write, and even illuminate (Kamm, 9), but also some nunneries where they were not taught. Noble girls might be sent to a convent school, but the educational content varied from place to place (Kamm, 22).

If you were not of sufficient rank to attend a convent school, there might be another option. An anchoress is a nun who has taken a vow of enclosure. Basically, voluntary imprisonment. Some anchoresses paid for their basic needs by encouraging the local children to come to the bars of her cell where she would teach them for a small fee (Kamm, 24).

In the non-Christian world, as far as I can tell, a girl’s best hope at formal education was still her father. In Heian Japan, noble girls’ education consisted of calligraphy, music, and poetry, all taught at home. It did not consist of Chinese classics. That was too mentally taxing, plus it led to showing off and intimidating the menfolk, which we definitely would not want. Murasaki Shikibu learned Chinese anyway by the time-honored method of listening in during her brother’s lessons. The answer to the “why” question here was because education in the acceptable disciplines made a woman more ornamental.

The Renaissance and the Reformation

Back in Europe, the Renaissance meant a growing interest in education, which belatedly included some females. Unsurprisingly, the earliest records are in Italy, home of the Renaissance. In 1403, one Leonardo Bruni wrote a letter laying out a girl’s study program. It is mildly interesting for what it includes: Latin, classical and Christian authors, writing, history. But it is far more interesting for what it does NOT include: “the subtleties of Arithmetic and Geometry are not worthy to absorb a cultivated mind” he says. That goes for boys and girls, but he goes on to say “You will be surprised to find me suggesting (though with much more hesitation) that the great and complex art of rhetoric should be placed in the same category. My chief reason is the obvious one, that I have in view the cultivation most fitting to a woman. To her neither the intricacies of debate nor the oratorical artifices of action and delivery are of the least practical use, if indeed they are not positively unbecoming” (Kersey, 23).

You really get the feeling Leonardo wants to make sure no man is ever embarrassed by losing an argument to a woman, right?

Even so, girls were slowly gaining educational ground, and then along came the Reformation. The short-term effect was equivalent to a wrecking ball. Protestant countries shut down the convents. Which is to say they shut down the only schools that existed for girls (Kersey, 42).

The long-term effect worked in the opposite direction. Martin Luther encouraged personal Bible study. Even for women, lowly as we are. Therefore, the answer to the “why” question is that it will be good for a girl’s soul if she is literate enough study the word of God.

Exactly when and how girls were gathering those literacy skills is still frustratingly undocumented. Many must have learned at home from busy parents in between other tasks. But slowly, slowly, we start to hear hints of other options.

Richard Mulcaster was a British schoolmaster for boys, but in 1581 he wrote a treatise on education for girls. He recommended teaching them both the playing of instruments and rhetoric, so times have changed, but he also drops a hint that girls might learn their lessons at a public elementary school (Kersey, 66). One can hope that such a school was not entirely theoretical?

The German principalities had elementary schools. They were among the first to require attendance for both boys and girls (Todd, 28). Sadly, it’s easier to make such a law than it is to enforce it, and there’s reason to suspect reality didn’t measure up.

School Choice

What definitely did exist were dame schools. These were informal affairs run by widows. To support themselves, they’d teach local children, boys and girls alike, for a small fee. And here at last, we get some details on methods, which we have not had since St Jerome.

For starters, many dame schools had a textbook. Sort of. It’s called a hornbook, and it was an oblong piece of wood with a handle. On the wood was a piece of parchment. The parchment had the alphabet, some common syllables, the Lord’s Prayer, and maybe (if your teacher was really ambitious) some Roman numerals. The parchment was covered with a very thin, transparent sheet of horn. (Yes, horn as in animal horn, or keratin, the stuff your nails are made of.) In a world before laminators, that was how you protected your parchment from the children. The handle had a hole in it so, it could be tied to the child’s belt when she was not actually studying it (Kamm, 34). If you had a particularly fun teacher, the hornbooks could also be made out of gingerbread. If you learned a letter to your teacher’s satisfaction, you got to eat the letter (Wyman, 303).

At dame schools, girls also learned basic sewing, Bible stories, and manners. But the women running these schools had no authority to compel attendance and a financial interest in taking as many students as they could possibly cram into their homes. So not ideal, but it was something.

If you could not afford the pretty cheap dame school, there might be another option. Charity schools began in the 1500s for the destitute children of major cities. These schools mostly get a bad reputation for being more interested in child labor than in child education (Kamm, 63). But there were exceptions.

The city of Venice had four such institutions, funded by the government and private donors. One of the four was the Ospedale della Pieta, where abandoned and orphaned girls learned music at a very high level. The girls were famous at the time. More famous today is their teacher and composer, Antonio Vivaldi (Wise). His most recognizable piece today is The Four Seasons, but he wrote many other specifically for these girls to learn.

The Enlightenment

In 1693, the highly influential John Locke, wrote Some Thoughts Concerning Education. It was written with a specific boy in mind, but Locke graciously allowed that there would be no difference for a girl (Kamm, 62). Locke’s big idea was that children are born as a blank slate, and their entire character, personality, everything is determined by their environment. He wasn’t the first to propose this, but what it meant was that education, was very, very important. Indeed, if you push it to the extreme, you can take it to mean that education is the only thing that matters.

Practically speaking, Locke said to indulge curiosity, answer questions, and read story books. Don’t bother memorizing Scripture until the kid’s old enough to understand it. Don’t bother with Latin until the local language is mastered. Also teach geography, astronomy, anatomy, history, dancing, and exercise (Kamin, 62). You can see that the curriculum has considerably expanded since the early days.

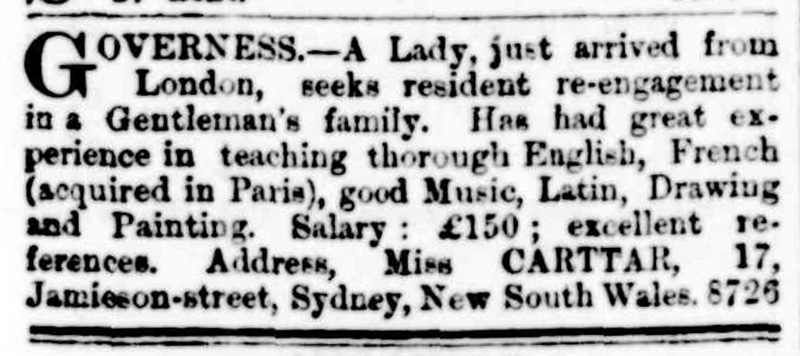

In the 18th century, educational opportunities and achievements exploded. The dame schools were still in full swing, but for older girls who could pay, there were now boarding schools. And for girls who could pay still more, a governess would come as a private tutor.

Even in backward places like the American colonies, progress was made. In 1700, two-thirds of American women could not write their own name. By 1800, the population was much larger, and two-thirds of American women could write their names (Mintz, 33). That’s maybe not a very high standard of education, but baby steps, people, baby steps.

That didn’t mean we’d reached any consensus on why we are educating girls. In 1762, Jean-Jacques Rousseau blithely wrote that the early education of males, depends on the women who take care of them. Therefore, “to oblige [males], to do us service, to gain our love and esteem, to rear us when young, to attend us when grown up … and to soften life with every kind of blandishment; these are the duties of [females] at all times, and what they ought to learn from their infancy. Unless they are guided by this principle, they will miss their aim” (Kersey, 133).

To that end, Rousseau recommends a lot of needlework, which he assures us girls really enjoy, and less reading and writing, which he assures us most girls have a vast aversion for anyway (Kersey, 13).

The stereotypical English boarding school seems to have taken Rousseau’s advice to heart. Many of them offered an advanced curriculum on how to catch a man. Posture, dress, manners, music, drawing, dancing, and how to gracefully enter and exit a carriage were often the main subjects taught. Mary Wollstonecraft had a very low opinion about the results, and she remarked that “if [girls] can play over a few tunes to their acquaintance, and have a drawing or two (half done by the master) to hang up in their rooms, they imagine themselves artists for the rest of their lives” (Kamm, 132).

It wasn’t that way everywhere. German schools were less thrilled about somewhat useless accomplishments and placed more emphasis on practical housekeeping skills. Which is better, if you ask me. But they mostly still denied girls the possibility of serious academics (Kasuga, 7).

Even worse was that boarding schools had a sketchy moral reputation. The popular wisdom among many families was that pubescent boys should go to boarding school. If they stayed home, they’d just get in trouble with the kitchen maids. But pubescent girls should stay at home. If they went to school, they’d run off with the dancing master.

Staying at home often meant a governess, and governesses presented their own set of problems. Very few of them entered the profession because they felt passionate about education. In a world where the ultimate goal for a girl was matrimony, a governess was, by definition, a girl who had failed. She was also as likely to be hampered by the parents as helped. Parents could interrupt lessons on a whim, undermine a governess’s attempts at discipline, or impose their own discipline willy nilly, and there was nothing a governess could do about it. As for qualifications, the governess had only what her own governess or boarding school had given her. So that varied wildly.

The difficulty of finding and retaining a good governess was a constant struggle, and it’s not very hard to see why. One mother wrote to her brother to see if he could recommend someone, saying:

“I require a person who is perfect mistress of music, drawing, dancing, geography, writing, arithmetic and French. She must not only understand French grammatically, but must be able to speak it correctly and elegantly. A knowledge of Italian would be a great recommendation. Other essentials it is almost unnecessary to mention; for, of course, she must be a gentle-woman in her manners, well-read, well-principled, and very good-tempered, fond of children, and not objecting to retirement, for we see very little company… I wish her to be about twenty-five.”

Quoted in Hope Deferred: Girls’ Education in English History, by Josephine Kamm, p. 134

To this the brother said not only did he not know anyone matching that description, but also that it would do his sister no good even if he did. He would marry a woman like that on the spot (Kamm, 134).

I don’t mean to say that no governess did a good job. There must have been many who did as well as the circumstances allowed, but the circumstances were, generally speaking, not in their favor.

19th Century Educational Reform

All of the above methods of education continued into the 19th century, but the 19th century was all about reform and progress and democracy. That last motive was an important point. In the newly formed United States of America there was a new answer to the question of why educate the girls. The answer was to make sure that the homes they would one day lead had good, solid democratic values that would produce upstanding citizens of our glorious republic, yes sir (Wright, 423).

Noah Webster would ultimately be most famous for his American dictionary, in which he removed some of the frivolously British letters, like the u’s in honour and favour. But much earlier, back in 1783, he didn’t want Americans importing British textbooks, so he published the Blue-Backed Speller that American children would use in school for the next 100 years.

American municipalities were banding together to build schoolhouses for these budding citizens, but compared with Europe, American municipalities tended to be young, small, and poor. Building separate schools for boys and girls wasn’t efficient. Hence co-ed schoolhouses, which turned out not to corrupt the morals after all. Or maybe it did on occasion, but it was still more practical than the alternative. As a side benefit, it also meant that education was more egalitarian because it’s harder to discriminate by gender when everyone’s packed in the same room.

High school was still only a glimmer in some reformers’ eyes. The first public high school for American girls was established in Boston in 1826. It closed after two years, but not because it failed. The mayor of Boston said it was “an alarming success.” Too many girls wanted to attend (Katsuya, 59).

The big push to open high schools only started succeeding in the 1880s, and it was not until the 20th century that it became the norm for teenagers to attend (Kamm, 216). High schools might be co-ed, or they might not. But even if it was available to all, gender discrepancies remained in large schools with options about what classes to take. Many high school girls chose to take no math class at all, and that was perfectly okay for a long time.

The concept of graded schools (as in grouping kids by age and covering certain topics at each age) was a new idea in the 1860s. It was only practical in metropolitan areas where a large school was trying to process lots of students. In smaller communities, the one-room schoolhouse would remain the norm into the 20th century (Wright, 3).

Throughout the 19th century more and more schools were established in many countries, and many of them were even funded at government expense, which meant they were no longer limited to those who could afford to pay. Even so, Britain did not make primary education compulsory until 1880. In the US, it’s hard to pin down a date because education is managed on a state-by-state level, but the process wasn’t complete until 1918 (Mintz, 174). And still the question remained, why are we educating the girls?

It was evident to everyone that a large percentage of girls grew up to become homemakers, not Latin scholars, and homemaking is a skill. A skill the girls weren’t learning at school, leaving them somewhat unprepared for the lives they would actually lead. Home economics as a school subject arose in the mid-19th century, and though it was dragged through the mud in the 20th century, it was feminists who were pushing it in the 19th (Dreilinger). Check out episodes 7.10 and 7.11 on housewives for more about that.

On the flip side, if we’re trying to educate girls so they’ll be prepared for employment outside the home, that’s a very different skill set. And potentially an embarrassing problem for men. As late as 1906, the Prussian government opposed schemes to put girls’ curriculums on an equal footing with boys because they were afraid of an “overproduction of highly educated women” (Kasuga, 52). I am happy to say the Prussian government caved eventually.

Education for Slaves and the Colonized

I cannot leave the subject of girls at school without acknowledging that the experience was very different for some girls. If you were a slave girl in the Ottoman Empire, you might get an education (see episode 4.3 on Roxelana). But for many owners, it was not only a waste of time to educate slave children, it was actually illegal.

If you weren’t a slave, but your country had been colonized, well, the 19th century activists pushing for educational reform at home had thoughts about that too. Children were blank slates, remember? So if we pull these little children of color away from their savage parents and educate them separately, then they’ll grow up to be like their teachers, not their parents, and they will be ever so grateful for it too, won’t they?

In the US and Canada, the Indian schools have made headlines in recent years as more and more has come out about how they operated. It isn’t pretty. The schools were under-funded and generally unregulated. Even if the adults in charge meant to be kind (and not all of them did), the fundamental concept was to explain to terrified children why our culture is better than your culture. Small wonder that the results were neither particularly educational nor in any way inspirational. Colonial powers ran similar schools around the world. Not all of them were blatantly abusive. But some of them were.

The 20th Century Surprise

In the late 20th century, the educational crisis shifted in a surprising way. For the first time in history, the girls outperformed the boys in academic subjects. Today, girls are more likely to graduate from high school, they score better than boys on reading and writing, and in many locations they even score better on math. These stats are for the United States, but there are similar trends in other countries, even as girls’ access to education remains a major problem in developing countries. There is obviously still a long way to go, but girls overall are at a historical highpoint regarding education. Schools seem to get bad reviews, what with all the varying answers to why are we educating the kids (a question that still isn’t fully resolved to everyone’s satisfaction). Even so, in comparison with the educational options for girls across history, I am now feeling pretty amazingly good about my local public school system. I hope the same is true for you.

Selected Sources

Clabaugh, Gary K. A History of Male Attitudes toward Educating Women. Institute of Education Sciences, files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ887227.pdf. Accessed 20 Nov. 2023.

Dreilinger, Danielle. The Secret History of Home Economics : How Trailblazing Women Harnessed the Power of Home and Changed the Way We Live. New York, N.Y., W. W. Norton & Company, 2021.

Kamm, Josephine. Hope Deferred: Girls’ Education in English History. Methuen & Co, 1965.

Kersey, Shirley Nelson. Classics in the Education of Girls and Women. Metuchen, N.J., Scarecrow Press, 1981.

Marten, James. The History of Childhood: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2 Aug. 2018.

Martin, Christopher. A Short History of English Schools, 1750-1965. Hove : Wayland, 1979.

Mintz, Steven. Huck’s Raft : A History of American Childhood. Cambridge, Mass., Belknap Press Of Harvard University Press, 2004.

Taylor, Molly P. M. “Looking in the Wrong Places: The Search for Female Literacy in Ancient Egypt.” Www.academia.edu, http://www.academia.edu/71054542/Looking_in_the_wrong_places_the_search_for_female_literacy_in_ancient_Egypt. Accessed 20 Nov. 2023.

Todd, Kim. Chrysalis : Maria Sibylla Merian and the Secrets of Metamorphosis. Editora: Orlando, Harcourt, 2007.

Wise, Brian. “Vivaldi and the Ospedale Della Pietà.” Explore Classical Music, http://www.exploreclassicalmusic.com/vivaldi-and-the-ospedale-della-piet. Accessed 22 Nov. 2023.

Wong Yin Lee (1995) women’s education in traditional and modern China, Women’s History Review, 4:3, 345-367, DOI: 10.1080/09612029500200092

Worsley, Lucy. Jane Austen at Home. London, Hodder, 2018.

Wright, Russell O. Chronology of Education in the United States. McFarland, 22 Feb. 2006.

Wyman, Andrea. “The Earliest Early Childhood Teachers: Women Teachers of America’s Dame Schools.” Young Children 50, no. 2 (1995): 29–32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42726988.

Yoshi Kasuya. A Comparative Study of the Secondary Education of Girls in England, Germany, and the United States. Columbia University, 1933.

Zhao, Ban. “Lessons for Women, Ban Zhao [Pan Chao, Ca. 45-116] | US-China Institute.” China.usc.edu, 13 Dec. 1901, china.usc.edu/lessons-women-ban-zhao-pan-chao-ca-45-116.

Bravo for this episode, friend. I love it. I don’t love that the commercial in the middle is much louder in volume than your lovely voice. Can you change that, please?

LikeLike

[…] first change was the rise of high schools. High schools are generally considered to be an improvement on the previous educational landscape, […]

LikeLike