Pretty much every history of child labor includes the statement “children have always worked,” and that is true. Some of those histories go on to say, “But it didn’t really become a problem until the Industrial Revolution” and that is nonsense.

The reason they say that is because everyone agrees that a child helping out on the family farm or in the family shop is fine. Good even. We have this mental image of boys learning craftsman’s skills under their father’s watchful gaze and girls learning domestic skills under mother’s gentle tutelage, everyone benefitting from good solid work ethic and loving family values that will stand them in good stead in future life. It’s all very idyllic, very Little House on the Prairie/Farmer Boyish. It’s beautiful, and it did happen. For some kids.

But a lot of kids were not having that experience. For starters, not every family is so all-fired loving, but I’m ignoring that for today. This episode is about the enormous number of kids for whom that whole image is wrong, loving family or not.

As I have said I don’t know how many times in this during this series, girls’ lives go mostly undocumented, but we know that some of them were working very, very hard long before the Industrial Revolution got going.

Evidence of Child Labor

Sometimes we know about it from archaeological evidence. For example, when Mt Vesuvius erupted in 79 CE, the ash buried Pompeii, as you likely know. It also buried the wealthier seaside resort town of Herculaneum. Picture wealthy seaside resort in your minds and then picture how much work is involved in running a place like that. Then ponder how 11.5% of the child skeletons recovered in Herculaneum already had bone lesions that only grow after years of hard repetitive manual labor (Capasso).

Sometimes we know about child labor through legal statutes. Back in the day, child labor laws weren’t about protecting kids from exploitation. They were about sending kids into exploitation. For example, a 1575 English statute set aside public funds to employ poor children, under the theory that it would “accustom them to labor” and “afford a prophylactic against vagabonds and paupers” (Trattner, 22). The firm implication in this and many other documents is that if an area has a problem with the homeless or the unemployed of any age, it is definitely because these people are too lazy to work. How could there possibly be any other reason? Therefore we must teach them to work.

Seventy-five years later the colonial legislature of Virginia made laws to set up workhouses for poor children to prevent the “sloth and idleness where with such young children are easily corrupted” (quoted in Mason). Indeed, idleness was the great evil to be avoided, not exploitation. Parental advice was more likely to be about not indulging your children than it was to be about overscheduling them.

There are also regulations on the record for apprenticeships. Most apprentices were boys for the simple reason that most of the trades were for boys. But girls were sometimes apprenticed in silk making, embroidery, and tailoring. By definition, an apprenticeship meant leaving home and family and putting yourself entirely at the mercy of the master. The regulations say the minimum age was 14, but no one was enforcing that. Apprentices might well be younger. Actually, the existence of the regulation practically proves it. We generally only make laws when we don’t like the decisions people are making naturally. Terms of apprenticeship were usually for seven years, and it was much like a term of indenture. Supposedly, an apprenticeship was both work and education. But it was the work part that made it worthwhile for the master. The situation was simply perfect for abuse and exploitation (Orme, 312).

Speaking of abuse and exploitation, sometimes we know about child labor merely from extrapolation. It is true that pretty much all of the detailed accounts of a girlhood in slavery are from after the Industrial Revolution, but we know that girls were slaves long before that. If the likes of Harriet Tubman, Elizabeth Keckly, and Harriet Hemings spent their girlhoods at work, why would we expect their predecessor’s lives to be any different? Actually if you look at the lives of slaves, they mostly weren’t working in industrialized fields. They were still doing all the labor by hand. Generally speaking, slave owners are not the drivers of technological progress. When you’re already heavily invested in human labor, why would you heavily invest in machines that would make your humans obsolete? So we can feel pretty confident that the work of slave girls in the 19th century was pretty similar to the work of slave girls in previous eras. More about that will be sprinkled through the rest of this episode, but I want to add that many of the slave experiences of hard work and harsh punishment were not unique to slaves. Poor children of every color and legal status had similar stories to tell.

And finally, sometimes we know about child labor from linguistic evidence. In English, a maid is a servant, always female, who cleans and fetches and carries and basically does all the tasks her employer doesn’t want to do. The same word is used to describe girls generally. A maid or a maiden is a young, unmarried, virginal girl, which is a clue to how old the servants often were (Orme, 309).

In medieval Europe it was common practice to send your daughters to serve in a household of a status higher than your own. For lower class girls this meant hard domestic labor, not under the gaze of your gentle mother, but under the gaze of strangers who might take a liking to you and raise your social status. But then again, they might not. even upper-class girls might be sent away from family to a foster family (Orme, 309-315). It is true these girls were probably not given the worst jobs, and hopefully got a stuffy room to sleep in. To be a lady-in-waiting was a serious step up from being the laundry girl, but it still meant being constantly at the queen’s beck and call fetching this, removing that, and delivering messages. It was still a form of work, though admittedly much better than what the lower class girls were doing. Like apprenticeships, the situation was a perfect setting for abuse of various kinds.

Domestic Service

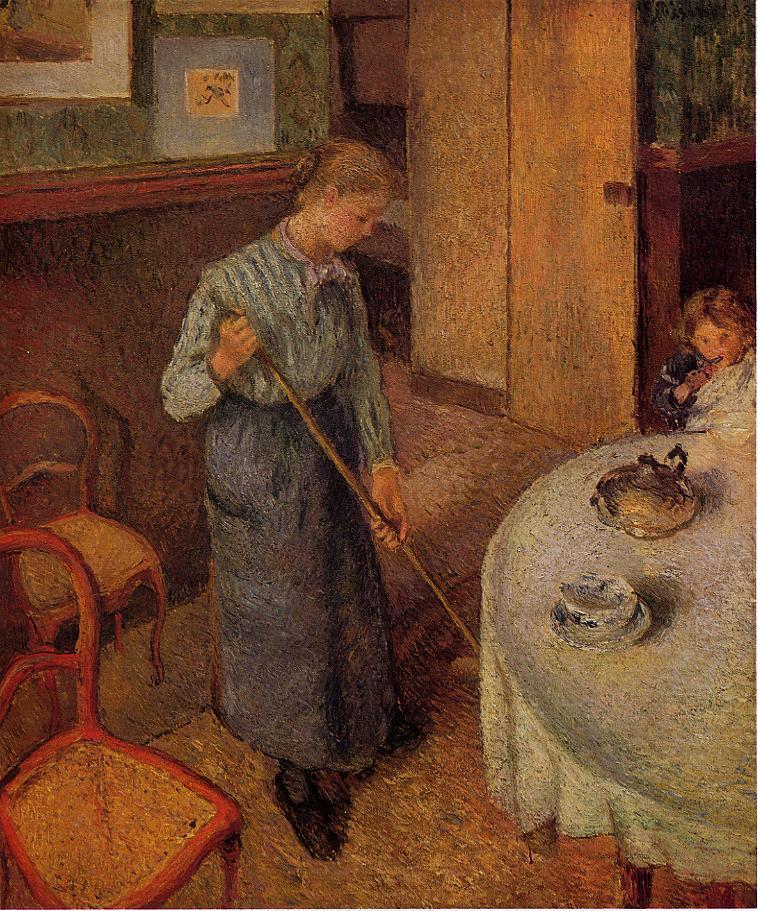

Maids commonly began work at ages twelve to fourteen. That was the mentioned and recommended age, but there was no enforcement, and often they were far younger than that (Orme, 309). Many of them came straight from having done very similar work in their own homes. Employers liked young servants because young servants were cheap. Sometimes you didn’t have to provide them with anything but bed and board.

Records of servants usually don’t mention how old the servant was. But once you realize how likely they were to be young, it does put a different light on the frequent complaint that servants were stupid and lazy. In many cases, what they really were was young and inexperienced. And I do have proof on that, or at least an anecdote on that, from none other than Harriet Tubman. She recalled that at the ripe old age of six or seven, she was sent to be a house servant for a young Miss Susan. Harriet, completely untrained, was told to sweep and dust. She did so, sweeping with all her strength, sending clouds of the floor dirt up into the air where it gradually settled on the furniture she had just dusted. Miss Susan returned and seeing all the dirt everywhere, assumed that Harriet had simply disobeyed her, and began whipping her. Not until Susan’s sister came to see what all the screaming was about did anyone teach Harriet how to do the job (Larson, 38-39).

Domestic servants continued to be commonplace well into the 20th century. In 1900, Britain raised the age for leaving school all the way up to 12 years old. But girls younger than that could be hired very cheaply to go to school part time and then work as a maid for not more than 27 and ½ hrs per week (Lethbridge, 65). I’m not sure why the half is in there, but it is.

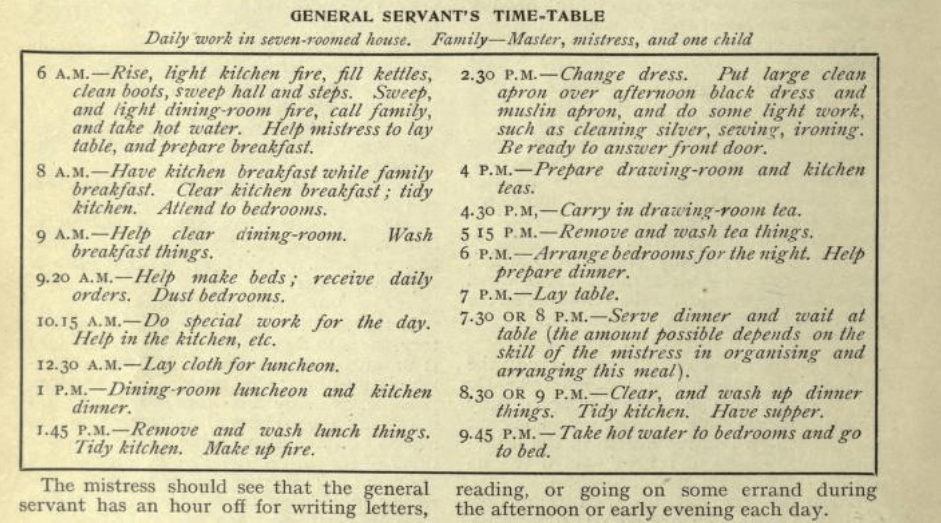

For full time maids, the hours were much, much longer than that. In 1910, the Every Woman’s Encyclopedia gave a suggested work schedule for a small household with father, mother, one child, and one maid. The maid is to rise at 6:00 am and start work immediately. She is busy every hour of the day until 9:45 pm, though underneath the schedule, a note does graciously allow that the mistress should ensure the maid has an hour off each afternoon or evening for writing letters, reading, or going on some errand of her own. Where that hour is supposed to fall is a mystery to me, since the schedule is pretty full.

At 9:45, a maid can deliver hot water to all the bedrooms before collapsing into her own bed.

I have already done a whole series on housework, so I’m not going to go over all the tasks that entailed, but rest assured there were girls helping or even entirely responsible for laundry, sewing, lighting, cleaning, shopping, taking out the trash, and cooking. There are also some other traditional girls’ jobs that I didn’t cover in series 7, so let’s talk about a few of those.

Carrying Water

First up, as a girl, you might spend a good part of your time carrying water. This is the kind of thing that really never makes it into the historical record because the girls doing it were almost never literate and the writers receiving the water paid no attention to how it got to them. But when we look at modern anthropological studies of communities without running water, what do we see? We see girls carrying water.

For example, in six rural villages in Limpopo province, South Africa, researchers in 2008 observed 22 women and 12 girls carrying water as opposed to only 1 man and 4 boys doing the same. The youngest child was six years old. Eleven of the 16 total children did this with no adult supervision. Most of them did it in containers carried on their heads. The minimum distance observed was 40 meters or about 130 feet. The maximum distance observed was 650 meters or almost half a mile. Some water carriers did this once a day. Some did it eight times per day. Some carried only 8 lbs at a time (that’s roughly one gallon’s worth). Others carried up to 60 lbs (27kg) at a time (or almost 8 gallons worth) on each trip (Geere).

Consider that the average American family uses more than 300 gallons of water per day. I for one would use a lot less if I had to carry it all in, but even at the minimum consumption levels, we’re talking about a massive time commitment. Also a massive health hazard. That study in Limpopo was actually about spinal injuries. You won’t be surprised that girls and women who do this report higher than average levels of neck and back pain.

Carrying water wasn’t just for girls who lived in remote villages either. In the supposedly enlightened 20th century, a British maid-of-all-work named Lillian Westall broke down under the strain of carrying hot water up and down stairs in a small household. A single maid in such a household was estimated to carry three tons of water a week. As Lillian herself commented, “This sort of work needed the stamina of an ox and years of semi-starvation meant I hadn’t this sort of strength” (quoted in Lethbridge, 27).

Babysitting

Another task for young girls could be watching the still younger children. This one maybe doesn’t sound so bad, right? But when I say young girls I really mean young. The idea that the pre-Industrial mom was always at home is just wrong in many cases. A great many women worked in ways that did not allow them to simultaneously watch their children.

For example, Harriet Tubman‘s mother left the slave cabin every morning because she was a cook up at the owner’s house. At the grand age of five, Harriet’s job was to babysit. Here’s her memory of it: “I had a nice frolic with that baby, swinging him all around, his feet in the dress and his little head and arms touching the floor, because I was too small to hold him higher. It was late nights before my mother got home, and when he’d get worrying I’d cut a fat chunk of pork and toast it on the coals and put it in his mouth. One night he went to sleep with that hanging out, and when my mother come home she thought I’d done kill him” (Larson, 20-21).

Harriet’s memory of this may be pleasant, but the modern mind boggles at leaving a five-year-old to handle knives, fire, and not just one, but actually two children smaller than herself. But what else could her mother do? This situation was not uncommon. Harriet doesn’t mention whether her mother was angry with her over that scare. The mistress probably never knew.

But the mistress probably did know when it was her own child at risk. Elizabeth Keckly was all of four years old when she was assigned to rock the cradle of her mistress’s baby. Elizabeth was eager to please. Maybe even overeager and excitable. She later recounted “I began to rock the cradle most industriously, when lo! out pitched little pet on the floor. I instantly cried out, ‘Oh! The baby is on the floor’ and, not knowing what to do, I seized the fire-shovel in my perplexity, and was trying to shovel up my tender charge, when my mistress called to me to let the child alone, and then ordered that I be taken out and lashed for my carelessness… This was the first time I was punished in this cruel way, but not the last” (Keckley, 8). You do wonder whether the mistress ever thought it was her fault for leaving a four-year-old in charge.

Farm Work

So far all of the work I’ve mentioned fits neatly into women’s work. But an enormous lot of girls were doing work that we, safe within our gender stereotypes, assume was for the boys and men. A lot of girls were out in the fields doing agricultural labor. Slave girls like Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth certainly were.

Native American girls also were. Mary Jemison was white, but in 1755 she was kidnapped by Native Americans who adopted her. Her memoir reported that all children, both boys and girls helped plant, tend, and harvest the corn (Jemison). It might not have been much different if she had not been kidnapped. A century earlier, a popular song in England warned British girls against going to the colonies, where they’ll spend their life with the axe, the hoe, the plow, and the cart. The chorus goes “When that I was weary, weary, weary, weary, O.” There’s a lot of weary’s in there. These girls were probably indentured servants, living, working, and frequently dying, a long way from any loving family.

Even those who were lucky enough to be in one of those loving, semi-prosperous families were doing more agricultural work than you might imagine. A relative of my own, born in 1890, and not in any way a slave or a servant, mentioned that she and her sisters got up early every morning to milk 8 cows, feed 30 sheep and a horse before walking to school, which started at nine. They did the same again at night before bedtime. And that’s on top of being asked to help around the house with the more traditionally feminine tasks (Neddo). Makes you wonder if your own teenagers have a right to complain, doesn’t it?

If you are noticing that almost all my examples are actually from post-Industrial times, well, yes, I noticed that too and it wasn’t for lack of looking. Unfortunately, earlier ages didn’t find poor children’s lives sufficiently interesting to give us much in the way of details. But so far these girls have all been doing tasks that needed to be done from time immemorial. These weren’t new tasks, and children had been doing them for millennia.

Children and the Industrial Revolution

But something changed with the Industrial Revolution, right? The reformers who started railing against child labor certainly thought so. But as you’ve seen, the Industrial Revolution didn’t invent child labor. It didn’t invent long hours, separation from family, tedious jobs, physical danger, or harsh treatment. All of that was already in place and no one seemed to think it was a problem worth mentioning.

The initial responses to industrialized child labor were positive. In 1789 a petition for a new cotton factory said such a development would “afford employment to a great number of women and children, many of whom will be otherwise useless, if not burdensome to society” (Trattner, 26).

In 1791 Alexander Hamilton (always a fan of development) said that manufacturing was great because “it rendered children more useful” than they would otherwise be (Trattner, 26).

And one newspaper noted with delight that factory work didn’t require hiring able-bodied men. In fact, it is “better done by little girls from six to twelve years old” (Trattner, 26).

Many of the early industrialized workers were also delighted. To see why you only have to look at where they were coming from. Girls who had worked hard for their parents or as domestic servants had never experienced a moment of their lives when their behavior and decisions were not scrutinized by their mother or mistress. At a factory, you might work a twelve-hour shift, six days a week, but the other twelve hours of each day were your own. Many girls had also never had any spending power to speak of before. Any amount of spending money is exciting when you’re coming from working hard on the family farm for nothing but room and board. Plenty of others girls were proud to hand over their wages to the family. They felt good about being fully capable contributors to their family survival. For some, this felt like freedom.

The work itself was also considered to be relatively light. For example, the most common job for a girl in a cotton mill was that of a spinner. A spinner’s job was to walk up and down the aisles, brushing lint away from the machinery and watching for breaks in the thread. If the spinner saw a break, her job was to tie up the ends. That’s it. That’s the whole job. Surely everyone agrees that is much less physically demanding than hauling three tons of water every week, right?

All in all, the industrial bosses gave themselves a generous pat on the back for being altruistic benefactors. They were bringing bread to the hungry, work to the idle, hope to the widows and the fatherless, stability and prosperity to the community. The fact that they were also making money hand over fist was pretty great too, but they would have been righteously offended to have anyone suggest that money was their only motivation.

Child Labor and Reform

Back in episode 4.1 on the history of slavery, I mentioned that the strangest thing about all the early source documents is the almost total lack of any moral handwringing about it. There’s an occasional comment about how masters should treat their slaves well, but it took a very, very long time before anyone suggested that the institution itself was at fault. That maybe there just shouldn’t be slaves, regardless of how you treat them.

That’s true for slavery and it’s even more true for child labor, whether as slaves or not. The silence in the record on that subject is deafening. Sometimes things don’t get written down because they are rare or absent. But at other times they don’t get recorded because they are so commonplace, so taken for granted that no one thinks to mention it. Child labor is one of those things. As the historian Mary Beard put it: “Child labor was the norm. It is not a problem, or even a category, that most [people] would have understood” (Beard, 402).

It is true that the Industrial Revolution created jobs for children that had never before existed. But the real change was in the Western view of childhood. The new view had people looking at hardworking children and asking, is that really what a girl should be doing with her time? Is “useful” vs. “burdensome” really the measuring stick we want to use for judging the youngest among us? Forget what’s best for society. Let’s start asking what’s best for the children. That was a new way of looking at things, and one that was highly contentious. More on that in the next espisode.

Selected Sources

Beard, Mary. SPQR : A History of Ancient Rome. London Profile Books, 2016.

Capasso, Luigi, and Luisa Di Domenicantonio. “Work-Related Syndesmoses on the Bones of Children Who Died at Herculaneum.” The Lancet, vol. 352, no. 9140, 14 Nov. 1998, p. 1634, http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(05)61104-X/fulltext, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61104-X. Accessed 6 Apr. 2020.

Every Woman’s Encyclopaedia. Vol. 1, London, Bouverie Street, London, E.C., 1910, archive.org/details/everywomansencyc01londuoft/page/n5/mode/2up. Accessed 9 Dec. 2023.

Geere, Jo-Anne L, et al. “Domestic Water Carrying and Its Implications for Health: A Review and Mixed Methods Pilot Study in Limpopo Province, South Africa.” Environmental Health, vol. 9, no. 1, 26 Aug. 2010, https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069x-9-52.

Jemison, Mrs. Mary. A Narrative of the Life of Mrs. Mary Jemison. 1823, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/6960/6960-h/6960-h.htm. Accessed 7 Dec. 2023.

Keckley, Elizabeth. Behind the Scenes ; or Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House / Elizabeth Keckley. New York, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Larson, Kate Clifford . Bound for the Promised Land. One World, 19 Feb. 2009.

Lethbridge, Lucy. Servants. A&C Black, 1 Jan. 2013.

Mason, Mary Ann. “From Father’s Property to Children’s Rights: A History of Child Custody Preview.” Berkeley Law, 1994, http://www.law.berkeley.edu/our-faculty/faculty-sites/mary-ann-mason/books/from-fathers-property-to-childrens-rights-a-history-of-child-custody-preview/.

Neddo Rasmussen, Ivie Grace. “Life Story.” Unpublished. Found among the papers of Milton J. Rasmussen. Available at Family Search. https://www.familysearch.org/photos/artifacts/6801950?p=2617253&returnLabel=Ivie%20Grace%20Neddo%20(KWCJ-KFG)&returnUrl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.familysearch.org%2Ftree%2Fperson%2Fmemories%2FKWCJ-KFG

Orme, Nicholas. Medieval Children. New Haven, Yale University Press, 2003.

Sabatella, Matthew. “The Distressed Damsel: About the Song.” Ballad of America, balladofamerica.org/distressed-damsel/.

Trattner, Walter I. Crusade for the Children. Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Company, 1970.

I love the maid’s schedule you included here because it also illustrates very well the meals they had in that period of time. They had 5 meals: breakfast, luncheon, tea, dinner, and supper. Naturally, tea and supper are more like snack times. But still– very different cultural eating habits.

LikeLike

[…] owners did not hire black children, which is a whole issue in and of itself. Black girls were still picking cotton or working as maids. Mill owners could claim they were helping white children because life in the mill was better than […]

LikeLike

[…] two episodes on girls at work, the answer is: it doesn’t. In hundreds of pages of material on girls as maids, girls as factory workers, girls as agricultural laborers, there was not one word on how they […]

LikeLike