If you have a passing familiarity with the Bible, you may be hazily aware of how an obscure Semitic-speaking tribe in the Middle East conquered the land of Canaan, had some glory days under King David and King Solomon, fell on harder times, got run over by Babylon, got free from Babylon, and tried to pick up the pieces with mixed results. That’s about where the narrative of the Old Testament ends, at least if you’re reading the Protestant English version. Then there’s a big gap before the New Testament opens with a different cast of characters, and no explanation of how we got there.

Our heroine today falls into the gap. Here’s what happened.

The Greeks Conquer the Middle East

In 334 BCE Alexander the Great decided that Macedonia (and indeed the whole Ionian peninsula) was too small to contain him. He went on an unstoppable rampage throughout the Middle East, over to the Indian ocean, but he died young. His generals squabbled over just who got which piece of the pie, but everywhere was dominated by Alexander’s Greek successors.

As far as Judea was concerned, the only question was whether they would answer to the Ptolemaic Greeks over in Egypt and or to the Seleucid Greeks up in Syria. And it was a question that had multiple answers depending on whose army happened to be bigger at the moment.

But there were a few upsides. For one thing, Greek culture had a few positive points, like drama and philosophy and wine and olive oil and an extensive trade network for luxury goods. Everybody likes that. More importantly, the Greeks were pretty open-minded about other people’s cultures and religions. So long as you paid taxes when asked, said the right placating words at the right time, and sent a percentage of your young men to die for causes you didn’t care less about, then they weren’t too fussed about who you prayed to or why or how. It was all the same to them. There was no forced conversion to Hellenic culture or pagan gods.

But then again, they largely didn’t need to. Luxury goods and the suave superiority of the rich and powerful are pretty effective conversion tools. Traditional Jews looked on with growing discomfort as their youth (and their leaders) got excited about things like the gymnasia, where men went to socialize and exercise (in the nude, for crying out loud) under the watchful gaze of wall murals of Zeus. But still, this was corruption, not outright conversion, and the leading question of the day was whether stuff like that actually conflicted with the Jewish religion or whether it was merely a distasteful waste of time.

All might have continued with everyone mostly content except that the Seleucid Emperor Antiochus Epiphanes changed his mind about all that live and let live stuff. He passed laws saying Jews had to eat pork and work on the Sabbath and stop mutilating their baby boys with circumcision. Instead, they should offer sacrifices to Zeus and other pagan gods. These things definitely did conflict with the Jewish religion. Oh, and Antiochus Epiphanes also sold the office of High Priest to the highest bidder (Atkinson, 11 and 45-47). That too.

The Rise of the Hasmoneans

In 167 BCE, a Jew named Mattathias, of the Hasmonean family, was so angry about all this that he killed one of his fellow Jews, as said Jew stepped up to a pagan altar to offer an enforced sacrifice. Mattathias also killed the Seleucid officer who was enforcing it. He then took to the hills, gathering the discontented as he went (1 Maccabeans 2:24-29). Mattathias didn’t live much longer, but his son Judas Maccabeus took up the fight and launched it into full scale revolt, which they won.

There are a great many more details which I am glossing over, but you can read about them in the Apocrypha, the books the Protestant English Bible cuts out.

By 140 BCE, Judea was an independent state, ruled by the Hasmonean dynasty. They didn’t yet call themselves kings (they had a different term) but for all intents and purposes, it was the same thing. For a family that rose to prominence by opposing Greek rule, the Hasmoneans turned out to be alarmingly Greek in thought and culture. And the most obvious example of that is a matter of names. Salome Alexandra was probably born in 141 BCE (Atkinson, 69). The name Salome is Jewish, from either Hebrew or Aramaic. The two languages are so closely related, it’s sometimes hard to tell. The name Alexandra is 100% Greek. And she is not the only Hasmonean to have a dual name.

The Jewish rabbis who subsequently wrote about her always call her Salome. But our best and most complete source is the historian Flavius Josephus, born a Jew, but a defector to the Romans, writing mostly to a Greek and Roman audience. He calls her Alexandra.

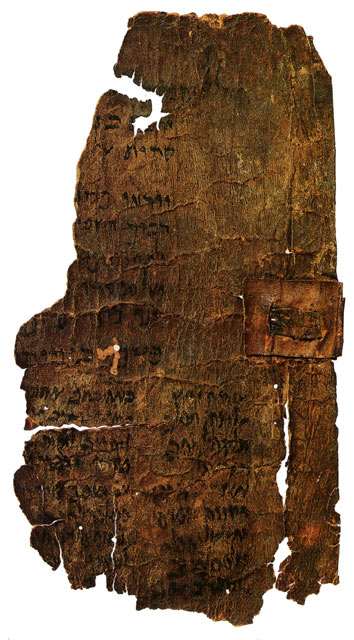

Meanwhile the Dead Sea Scrolls, some of which were written during her own lifetime, call her Shelamzion, or Schlomtzion or any of half a dozen other transliterations. Since Hebrew and Aramaic don’t include the vowels when written, multiple pronunciations are possible. Actually every proper noun in this episode has a bewildering array of possible pronunciations. I’m just picking one and going with it. In Hebrew Shelamzion means the Peace of Zion, and in Aramaic, it means the Perfection of Zion. Zion was a synonym for Jerusalem or sometimes the entire land of Israel. The people of God, anyway.

Either way, Salome is a shortening of that full name Shelamzion. It just drops off the Zion bit, and shifts around the vowels again (Atkinson, 22).

How much of this Salome’s parents thought through when they named her, I don’t know because no one knows who her parents were of if they even chose those names. Her entire childhood is a mystery. There is no source at all. The best we can do is make some educated guesses. It is likely that Salome was born a member of the Hasmonean extended family, but not in the direct line. That means her heritage was from rural Judea, but her family had probably moved to the center of power in Jerusalem (Atkinson, 61).

Living Under John Hyrcanus

If so, she was a child and inside the city when the Seleucid army lay siege to it. Siege warfare brings out the absolute worst in human nature. John Hyrcanus was the Hasmonean king and Jewish high priest in Jerusalem at the time, and he soon realized that he had fighting men to make sallies out and defend the city but many of the dwindling provisions were being eaten by everyone else. That is to say, the women, the children, the elderly, and the sick. He therefore—and I quote— “separated the useless part, and excluded them out of the city, and retained that part only which were in the flower of their age, and fit for war.” The misery of those useless people did not end there because Antiochus would not let those who were excluded just go away. They therefore sat trapped between the city walls and the besieging army, and they began to starve. “When the feast of tabernacles was at hand, those that were within commiserated their condition, and received them in again” (Josephus, Antiquities, Book 13, chapter 8).

So not the king. Just the regular people, opened the doors and let them in.

Salome was both female and a child, the very definition of useless. It is possible that as a member of the Hasmonean family she was spared this. But even if so, it’s likely she knew what was happening.

In the end John Hyrcanus and the Seleucids came to an arrangement. It involved plundering the tomb of King David for ready cash, but it worked. Judea remained at least nominally independent (Atkinson,77).

It was probably this same John Hyrcanus who later arranged Salome’s marriage. As you’ll see, there’s a lot of dispute about her marriage, but according to this first theory, in about 111 BCE Salome married John Hyrcanus’s son Alexander Jannaeus. She was, by Josephus’s dates, 29 years old at the time. Alexander Jannaeus was a ripe old 15, which makes it real hard to believe this was a love match (Atkinson, 62).

It is partly to resolve modern distaste at the age gap that some scholars have suggested this was a levirate marriage. That is to say, Alexander Jannaeus married her because she was his brother’s widow, and that was the traditional way of providing for widows. That could be true, but it’s problematic to think that Salome was married to his brother. There’s no clear evidence on it, and some cultural reasons why that would not be so (Ilan). The truth is a wide age gap, even one with the bride for older ws not uncommon when the reasons for marriage were political and financial. No one cared if they found each other attractive. That wasn’t the point.

At any rate, the man in charge was still John Hyrcanus, and he was in expansion mode. It was about this same time that he added Samaria to the kingdom. Other places too, but Samaria is the one that becomes a setting for some scenes from the New Testament.

It is also during John Hyrcanus’s time that Judaism splintered into the groups very familiar to New Testament readers. The Sadducees were your uppity elites. They were the ones running the temple, presiding over the festivals, filling the courts, and the army. Basically, the old guard. They believed in the Written Torah as the source of Divine Authority. That would be the first five books of the Old Testament: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.

The Pharisees were not the elites. In fact, they tended to think the Sadducees had become too big for their britches and altogether too Greek. Not real Jews. Not truly committed to God. The Pharisees accepted the Written Torah, but they also believed in the Oral Torah (Atkinson, 86), which is basically all the stuff after the first five books of the Old Testament, plus a lot more. It hadn’t all been written down yet, certainly not compiled, but for the Pharisees it was also a repository of God’s word.

The Hasmoneans were originally Pharisees, a family of the people. But then one of the Pharisees said John Hyrcanus was a bastard and therefore didn’t qualify to be high priest. King, yes. High priest, no. Whereupon John Hyrcanus got mad and declared that he and his sons were now Sadducees (Atkinson, 86; Zeitlin, 2).

One of the few things the sources agree on is that Salome was a lifelong Pharisee. It is possible that the reason she was a good match for Alexander Jannaeus was that she was a sop to the Pharisees, so they could feel like they still had influence. Or maybe not, because Alexander Jannaeus was not the obvious successor to the throne. He had an older brother. And anyway John Hyrcanus left the kingdom to his wife. Yup, that’s right. King John Hyrcanus did not leave the kingdom to his son (any of them). He left it to his wife (Josephus, Antiquities, book 13, chapter 11).

This was not as unusual as you might think. The Jews had had powerful queens in the past and the larger area was stuffed with strong women. Ptolemaic Egypt was currently ruled by Cleopatra. (Not that Cleopatra; this is an earlier one, Cleopatra III). The Seleucids had also had a queen regnant in living memory, unhelpfully named Cleopatra. Only a couple of decades on they would have another queen regnant, also named Cleopatra. I swear they do this solely for the purpose of being confusing.

Anyway, John Hyrcanus left his kingdom to his wife, but his oldest son was having none of that. Aristobulus imprisoned his own mother and let her die of starvation (Josephus, Antiquities, book 13, chapter 11). He also imprisoned three of his four brothers, including Alexander Janneaus. Aristobulus was the first Hasmonean to call himself king, not just ethnarch (Zeitlin, 3).

But he ruled for only one year before he died (possibly murdered), and here is where the practice of naming everybody with pretty much the same names gets us into serious trouble. According to Josephus, Aristobulus’s wife Salina released the prisoners and made Alexander Janneaus king (Josephus, Antiquities, book 13, chapter 12). Yes, she, a woman chose the next king. That’s not the problem.

The problem is that the name Salina is awfully close to Salome, especially if your written language doesn’t believe in vowels. Since, as I mentioned, some people think Salome and Alexander Janneaus had a levirate marriage, they have then assumed that our Salome was Aristobulus’s wife, that she married Alexander Janneaus later, and Salina and Salome are the same person. In other words, she made him king and then she married him.

The problems with that theory are that (a) the birth of Salome and Alexander Janneaus’s first child suggests they were already married. As far as I can tell, that’s the main reason for thinking they were married back in 111 BCE. And (b) if Josephus meant Salome, why did he write Salina? The book in question is called The Antiquities, and it was written in Greek. Greek has vowels. It seems simpler to assume that when he wrote Salome he meant Salome and when he wrote Salina, he meant someone else, and that is the opinion of several of my sources (Atkinson, Ilan), but not all.

Queen Consort

However they got there, Alexander Jannaeus was now king and high priest, and Salome was his wife. Alexander Jannaeus ruled for the next 27 years, and nothing he did during that time seems likely to impress you. He murdered his rivals, accidentally got Judea entangled in Egyptian dynastic wars, won a few new territories, but also lost some battles. Of particular interest, given current events, he won Gaza. Five hundred of the people took refuge in their temple. Alexander Jannaeus slaughtered them all (Josephus, Antiquities, book 13, chapter 13).

He wasn’t any too kind to his own people either. Some of them threw citrons at him during the feast of tabernacles and in response he killed 6,000 of them (Josephus, Antiquities, book 13, chapter 13). Then they rose up in revolt and he crucified a bunch more (Josephus, Antiquities, book 13, chapter 14).

The Dead Sea Scrolls (which would more accurately be named the Dead Sea Fragments) have a little scrap of a prayer about Alexander Jannaeus. But just to show you how difficult it is to be sure about anything in this time period, let me read you two different translations of the opening: It starts either as “Keep guard, O Holy One, over King [Jannaeus] and over all the congregation of your people… let them have peace” (Eschel, 647).

Or it reads “Rise up, O Holy One, against King [Jannaeus] and as for the congregation of Thy people, … let them have peace” (Atkinson, 140; Main, 135).

Yes, that’s right: the translators can’t even agree on whether the author of this prayer is saying God bless the king and keep him or Please, God, get rid of this guy. We hate him.

What Salome was doing during all this is not in the record. But she certainly raised a couple of sons, and it would not have been unusual in the climate of the times for her to be doing the ins and outs of actually running the country while Alexander Jannaeus was out on campaigns. She may even have been an officially recognized regent or co-ruler. Nothing in the record comes out and says that. But it would explain why when Alexander Jannaeus died after 27 years of bloodshed on the throne, the kingdom was left not to either of his fully grown sons, but to his wife. She was 64 years old, and she was Queen Regnant.

Queen Regnant

The beginning of her reign presented an immediate challenge, in that Alexander Jannaeus was actually mid-campaign when he died, besieging a fortress called Ragaba. According to one of Josephus’s accounts, Alexander Jannaeus suggested Salome conceal his death until she had captured it, so she could return to Jerusalem in triumph and thus secure her rule (Josephus, Antiquities, book 13, chapter 15), which she did handily.

Josephus’s other account of this doesn’t say any of that. It says that everyone already loved her because she had opposed Alexander Jannaeus’s cruelties in the past (Josephus, War, chapter 5).

Most distressingly for me, Josephus has a lot less to say about Salome’s reign than he did about her predecessors. That is partly because it was shorter (a mere nine years), partly because Josephus disapproves of women, but I think it was mostly because Salome’s reign was a time of peace. Like scads of other mostly male historians after him, Josephus just can’t find that much to talk about when the people aren’t hacking each other to bloody bits.

For example, we do know that during Salome’s reign, Tigranes, the king of Armenia, invaded. Salome had an army. She had kept it up and even increased it. But she opted for a diplomatic solution, sending ambassadors (and gifts) to ask him not to bother Judea. Amazingly, he agreed. Or perhaps not so amazingly, given that he’d just receive word that Rome had just attacked his home in Armenia. He had good reason to scurry away (Josephus, Antiquities, book 13, chapter 16). But Salome was smart enough to call that victory and leave it alone. Her counterpart in the Seleucid Empire, Cleopatra Selene, did not call that victory. She pursued Tigranes, provoked a battle, and got herself killed (Atkinson, 218).

Salome also had a spot of trouble with her own son, who rebelled against her. Josephus’s two accounts of this are rather confused. It’s not even clear whether her son revolted twice or just once. What is clear is that Salome remained on the throne.

The accounts (not just Josephus’s) disagree on whether and how many additional territories she gathered. Even some that were definitely brought into Judea may have been her victories or they may have been Alexander Jannaeus’s. Either way, not a lot of details (Atkinson, 152).

All accounts agree that Salome relied heavily on the Pharisees for administrative help. Josephus manages to make this sound like a bad thing. He clearly doesn’t approve of her having given so much weight to Pharisee advisors, but he does graciously admit that sometimes men also show little understanding and make mistakes in government (Josephus, Antiquities, book 13, chapter 16). So, thanks for that, Josephus. Way to state the obvious.

Even Josephus admits that she was “a sagacious woman in the management of great affairs,” that she strengthened the army until Judea “became not only very powerful at home, but terrible also to foreign potentates” (Josephus, War, book 8, chapter 5), that “her mind was fit for action,” and “that she preserved the nation in peace” (Josephus, Antiquities, book 13, chapter 16).

All that sounds pretty good to me, but Josephus still manages to be a bit down on her. He claims that she left the kingdom in an unfortunate condition, though he’s fuzzy on details since it doesn’t sound all that unfortunate to me (Josephus, Antiquities, book 13, chapter 16).

The rabbinical literature leaves no such reservations or backhanded stabs. On the contrary, they claim that “in the days of Queen Salome rain fell on Sabbath nights until wheat grew to the size of kidneys, barley to that of olive berries, lentils to that of gold denarii” (Freedman, 452; Atkinson, 161).

The golden age lasted for nine years until 69 BCE when Salome died peacefully at the age of 73. (Atkinson, 222).

Her two sons immediately fell into war over who would inherit the kingdom. They were still at it when Rome decided that they couldn’t think of any good reason why this part of the world shouldn’t be part of Rome. General Pompey carried that out swiftly and decisively, in a military victory which I previously described in episode 5.1 on the background to the Virgin Mary’s story. From this point on, Judea paid tribute to Rome and abided by Roman laws, which is why Salome was the last queen and the last independent ruler of Judea.

No one, man or woman, would rule an independent Jewish state for another 2,000 years. Until May 14, 1948, to be precise, when the modern state of Israel declared its independence. They don’t have a monarch of any gender, but they have had a female prime minister.

Speaking of Israel, I wrote this episode while Israel was in the news every day with stories that are as full of death, violence, trauma, and heartbreak as the one I’ve just told. I have a strict policy of not having any political opinions on this podcast, but in case any of you are wondering whether this series will include any Arab or Muslim queens, the answer is yes. Yes, it will.

Selected Sources

Atkinson, Kenneth. Queen Salome. McFarland, 10 Jan. 2014.

Eshel, Hanan, and Esther Eshel. “4Q448, Psalm 154 (Syriac), Sirach 48:20, and 4QpIsaa.” Journal of Biblical Literature 119, no. 4 (2000): 645–59. https://doi.org/10.2307/3268520.

Freedman, Harry, and Maurice Simon, eds. Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Soncino Press, 1939, archive.org/details/midrashrabbah0000unse/page/n5/mode/2up. Accessed 17 Jan. 2024.

Ilan, Tal. “Queen Salamzion Alexandra and Judas Aristobulus I’s Widow: Did Jannaeus Alexander Contract a Levirate Marriage?” Journal for the Study of Judaism in the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman Period 24, no. 2 (1993): 181–90. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24659932.

Josephus, Flavius. “Antiquities of the Jews.” Https://Www.gutenberg.org/Files/2848/2848-h/2848-H.htm, http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/2848/pg2848-images.html. Accessed 17 Jan. 2024.

—. “The Wars of the Jews; Or, the History of the Destruction of Jerusalem.” Https://Www.gutenberg.org/Files/2850/2850-h/2850-H.htm, http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/2850/pg2850-images.html. Accessed 17 Jan. 2024.

Main, Emmanuelle, “For King Jonathan or Against? The Use of the Bible in 4Q448.” Biblical Perspectives: Early Use and Interpretation of the Bible in Light of the Dead Sea Scrolls, 1998, 113–35. doi:10.1163/9789004350298_009.

Highly entertaining and funny, as usual. More so than your two previous guests.

Also, have you got a cold? Something’s definitely up with your voice.

LikeLike

[…] We don’t get to know how Alexander would have handled that bit of insubordination because he died. Suddenly, unexpectedly, and leaving the known world in political chaos as each of his generals and hangers on tried to claim the biggest piece of the empire. That struggle would have ramifications for centuries, including shaping the world of Cleopatra (yes, that Cleopatra, episode 2.2) and Salome Alexandra (episode 12.1). […]

LikeLike