You know how first-time parents take lots of pictures and document all the milestones and cute moments? But with child number two, they are busier and it’s not new anymore, so they document less. And still less than that for child number three, not to mention number four and number five?

Well, imagine being child number fifteen. Yes, that’s right. Maria Theresa was the Empress Regnant of the Habsburg empire, based in what is now Austria. In her spare time, she gave birth 16 times within 19 years. Clearly, this is a woman who needs her own episode, but for today the point is that the 15ᵗʰ child was Maria Antonia, born November 2, 1755, and that’s about as much as we know about her early childhood. Princess though she was, childhood wasn’t yet a particularly celebrated stage of life, and it’s not like there weren’t a gaggle of other princesses, so we get no hard details.

It is true that a child prodigy named Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart visited her palace when she was seven, and so was he, more or less. But the anecdote that they met, and that he declared he would marry her someday, is probably not true (Timms).

The Proposal

What we do know is that the value of having a lot of girls in a royal family is so that you can marry them off in politically advantageous ways. And the political advantage Maria Theresa most wanted was an alliance with France. Traditionally, France and Austria were not friends (far from it), but Maria Theresa pressed long and hard about changing that.

There was some doubt about who exactly should be offered up as a sacrifice to achieve this goal. The doubt existed on both sides. On the Austrian side, they were spoiled for choice. A handful of the princesses were still unmarried. Any of them would have satisfied their mother’s plans. It really didn’t matter.

On the French side, there was an old king called Louis XV, and his wife was dead, so that put him back on the dating market. There was the crown prince, always called by his title, the dauphin, even when writing in English. The dauphin was not Louis XVth’s son (who had died), but his grandson, still a boy, but we don’t really have a minimum age on the dating app, so that put him on the market. Either the king or the dauphin would have been an acceptable groom.

Princess Maria Elisabeth (child number six) was proposed as a bride for Louis XV. The 33-year age difference between them was no problem. The fact that he had a string of high profile utterly unconcealed mistresses was also no biggie. When I say unconcealed, I mean it. The king’s mistress was an official position. It came with its own staff.

The proposal actually got scotched on the French side. Maria Elisabeth had been famed for her beauty, but then: smallpox. The girl survived. Her beauty did not, and when this was reported to Louis, he decided he liked being a bachelor after all (Goldstone, 235).

Instead, Louis XV agreed that the dauphin would wed. Not Maria Elizabeth (no pock marks in France, please), but one of the younger daughters of Maria Theresa would do.

As a side note, Maria Elisabeth never did find a man who could look past her ravaged face. She was sent to a convent instead, crying all the way. She did not live a monastic lifestyle but entertained a lot and traveled (Goldstone, 236). Given what later happened in France, I think she got the better end of the deal, but I doubt that it felt like that at the time.

Anyway, that was how Maria Antonia became the luckiest of all the princesses, with a match that not one of her older sisters could rival, for the French court was the wealthiest, the most prestigious, the most glittering in all of Europe. It was the cultural and intellectual capital of the continent, and she was to become its next queen. She was 13 years old.

The Bride

Think of the 13-year-olds you know. Are they ready for marriage? Ready for permanent emigration away from their family? Ready to be showered with wealth, adulation, and power over other people’s lives?

Yeah, Marie Antoinette wasn’t ready either and everybody knew it. Maria Theresa hastily engaged tutors in music, art, and ballet. (Goldstone, 237). One wonders why she had not already done so? But I can allow that the empress was a busy woman with other things (and other daughters) to think about.

The French court sent their own tutor because they clearly didn’t think the Viennese court could handle it. And they were right. We have a dozen surviving letters from this tutor, and he says that Marie Antoinette spoke French “of a sort.” Her handwriting was inconceivably slow. Her spelling was appalling. He judged that she was quick on the uptake, but she was bad on the retention. He felt that she was capable of learning if only she weren’t so distracted (Hardman, Marie Antoinette, 5- 7).

It is partially this tutor’s comments that have led modern writers to suggest that Marie Antoinette had ADHD (Goldstone, 237). That could be. But a diagnosis at this distance is impossible and it occurs to me to wonder how much experience the tutor had with children. I poked around a little into his background, but it was a question I was unable to answer. If he didn’t have much experience, I think it’s possible that his expectations were unreasonable for a 13-year-old.

Besides all the lessons, there were the questions of physical appearance. She was pock-free, I presume, but what about her posture? And her figure? And her hair? And her wardrobe? And her teeth? Yes, it turns out that the history of modern orthodontics does begin in 18ᵗʰ century France, and Marie Antoinette’s teeth were not good enough for the French court. All the sources on her left me discreetly in the dark about how exactly the straightening was accomplished, but contemporary manuals for dentists do exist. In them the father of modern dentistry calmly explains how he operated on a patient every day for two months with the help of wires and a silver blade, and at the end of it, voilá, all the teeth that were out of alignment are now “as beautiful and good; as they were previously deformed and bad.” (Fouchard, chapter 28, 1st observation).

When you remember that modern orthodontics has anesthesia and spends a lot longer than two months accomplishing the same thing? Yeesh, this sounds like excruciating agony, but there we are. Beauty hurts.

The Court

A few months and an enormous amount of money was all her teeth, her French, and her deportment were going to get because Marie Antoinette was now 14, and it was wedding time, ready or not. She was married in Vienna on April 19, 1770. Her groom didn’t show, but then again, he wasn’t expected to. Her brother filled in as proxy during the service. Then there were two days of outrageously expensive partying before she began her one-way journey into France.

If there were few sources about her childhood as 15ᵗʰ child of the Empress, now she is the dauphine of France, and from this point on we are drowning in sources. She wrote plenty of correspondence herself. People also wrote letters to her. The people around her wrote letters to each other behind her back. The press wrote about her. Her lady-in-waiting wrote a memoir about her. Her friend, Princess Lamballe, wrote a memoir. Her painter wrote a memoir, which I have previously referenced on this podcast, episode 10.7 Elisabeth Vigée le Brun. Even her hairdresser and her executioner wrote memoirs. (I hope that wasn’t a spoiler for you. Yes, we are headed toward an execution, but we won’t get there this week.)

Every one of these people wrote with their own agenda top of mind. Historical accuracy was never the agenda. The accounts conflict as people fabricated, or embellished, or neglected to mention, or reported gossip as fact, or just flat-out lied. It’s bewildering, and sometimes impossible to sort out from this distance.

The court that Marie Antoinette moved into was a complicated one. In many countries, the nobility are dispersed around the country, each on their individual estates, only coming together on occasion. Not so in France.

Louis XIV, the long-lived Sun King, had encouraged all nobles to come to Versailles on a permanent basis, where he could keep an eye on them. And now near the end of end of the long-lived Louis XV’s reign, those nobles’ descendants were all still there. Sure, the royal family kept an eye on the nobles, but the nobles also kept an eye on the royal family. Literally every moment of Marie Antoinette’s day was regimented by 100 years of longstanding etiquette and accompanied by a crowd of onlookers, some of whom had official and paid positions which permitted them to help her with this or that small task. Marie Antoinette wrote to her mother that in the mornings, “I put on my rouge and wash my hands before everybody, after which the men go out and the ladies remain, and I dress myself before them” (Hearsey, 22).

This level of scrutiny and adulation is not ideal for your average fourteen-year-old. And adulation isn’t even quite the right word. All these people wanted something from her too, whether it was the promise of future favors, a better court position, or her support for them in their own intrigue against another member of court. And there were intrigues a plenty.

The most serious intrigue revolved around Madame du Barry, the old king’s current mistress. Innocent little Marie Antoinette did not initially understand du Barry’s role at court (Hearsey, 22), but soon enough the cold facts were explained to her. Madame du Barry was a low born, illegitimate, former prostitute and street vendor who caught the eye of the king. There was etiquette and protocol even for mistresses, and she didn’t measure up because she didn’t have a title, so some small count had been rustled up from the backwaters and ordered to marry her. Now that she was a countess, she was qualified to be the king’s official mistress, and protocol was happy even if a lot of other people weren’t.

Chief among the unhappy people were the three adult daughters of the king. Historians in general are not kind to these women, calling them prudes (Hardman, Marie Antoinette, 15) and self-righteous (Hearsey, 26) and worse. But just think about it. Three single women who still lived at home because moving out was never one of their options. Their Mom dies and Dad takes up with a floozy, 33 years his junior. She is clearly there for whatever she can get out of him. Would you expect them to like her? Of course they didn’t like her.

Marie Antoinette had been told by her mother to take her social cues from these three women (who were the highest-ranking women in the court), and Marie Antoinette obediently did. She followed their lead in refusing to acknowledge Madame du Barry’s existence (Hardman, Marie Antoinette, 15). Not a word, not a nod. It was like the floozy was both invisible and inaudible.

But soon Maria Theresa and the Austrian ambassador were begging her to do differently because France and Austria were currently divvying up Poland between them, and Louis XV was a lot more interested in the happiness of his mistress than he was in Poland. So long as du Barry felt slighted, he would sign nothing, and Maria Theresa was exasperatedly writing to her daughter: Would it hurt you just to say hello to the woman?

And finally, Marie Antoinette did. On January 1, 1772, she said: “There are a lot of people at Versailles today.” An utterly banal sentence, but it was acknowledgment, so Madame du Barry was happy, so the king was happy, so he agreed Austria could have the best piece of Poland, and so Maria Theresa was happy (Hardman, Marie Antoinette, 17; Hearsey, 27). Presumably the Poles were not, but they were going to lose either way.

Really, the whole episode gives me flashbacks to middle school social interactions. Only way worse, because the stakes were astronomically higher, and there was no expectation that anyone was ever going to grow up. This is just one of many examples of what counted as good governance in Europe’s most glittering court.

Obviously, what France needed was a younger, bolder, and more dynamic king. One who would inspire, lead, command loyalty, and encourage people’s better natures, rather than their worst instincts. One who wanted to actually govern and improve people’s lives. So let’s take a look at the dauphin, husband of Marie Antoinette, about whom I have thus far said almost nothing because he deserves his own explanation.

The Groom

Louis-Auguste was born one year before his bride in 1754. No one expected him to inherit the throne. Not only was it expected to go to his father, but even after that, it was expected to go to his older brother, who was handsome and charming and everything one could want in a young prince.

Louis-Auguste was sickly, awkward, and gangly. His older brother outshone him and bullied him. Even his younger brother outshone him in many ways.

Louis-Auguste’s behavior baffled and irritated the people around him. For example, his aunt tried to make him comfortable by telling him that in her rooms it was just fine to talk, yell, make noise, break things, whatever. In other words, be a normal child. But he didn’t (Goldstone, 248).

With his tutor, Louis was great at facts and figures. Geography and physics, he loved. He could conjugate verbs in a half dozen languages. He also enjoyed locksmithing. One can imagine that in a different world, he could have had an excellent career in any of those fields.

But being king is not about facts and figures. It’s about people and relationships and force of personality, none of which work according to an equation or a timetable. In these areas, Louis was quite remarkably lacking. At the age of 11 he wrote (and published) a meticulous pamphlet describing the Forest of Compiégne. It is remarkably accurate with regard to acreages and physical structures. It has not one word regarding beauty, color, pleasure in the scene, personal judgment, or any thought beyond the strict facts (Hardman, Louis XVI, 24).

His diary, which he kept throughout his life, is the same. More than half of the entries contain nothing beyond what he killed in the hunt that day. When he did have another event he deemed worth recording, the entries are totally devoid of emotion. For example, on March 13, 1767, his record says, “Death of my mother at 8 in the evening” (Goldstone, 250). One gets the sense that a dental hygiene appointment would be recorded in exactly the same way.

Nothing changes as he grows older. Each entry is as bland as the last one, with the entry for July 14, 1789, perhaps taking the prize for startling obtuseness. That was the day revolutionaries stormed the Bastille, now celebrated as a French holiday every year. It was absolutely momentous from every angle. Louis’s diary says Rien, which means “nothing,” as in he didn’t shoot anything that day, and he didn’t think it worth writing about anything else that may have happened that day (Hardman, Louix XVI, 22).

Throughout his life, Louis-Auguste would demonstrate an astonishing ability to compile all the facts and figures to explain why France should take a particular course, only to have someone with less knowledge and more personality talk him into doing the exact opposite.

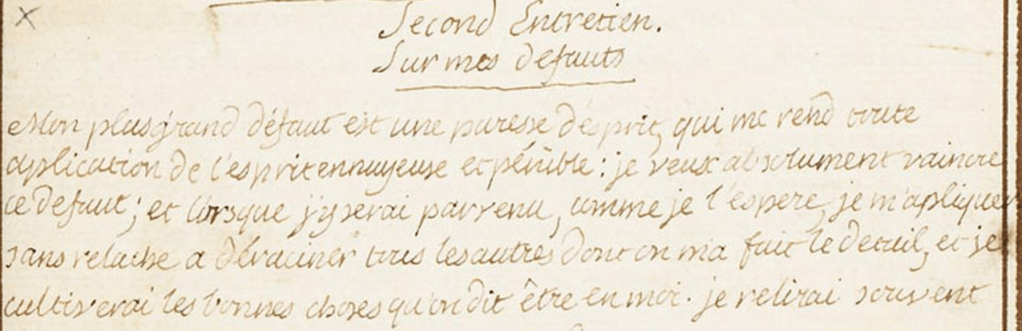

One modern author has suggested that he had autism (Goldstone, 251). Again, it’s impossible to diagnose at this distance, but certainly social skills were not his gift. And it is all the more heart breaking to realize that he was trying. His school notebooks contain an essay which he titled “Concerning My Faults.” It begins, “My greatest fault is a sluggishness of mind which makes all my mental efforts wearisome and painful: I want absolutely to conquer this defect; and after I have done so, as I hope to, I shall apply myself without respite to uprooting all the others which have been pointed out to me” (Padover, 16).

Not much later, he welcomed Marie Antoinette to France as his bride. His diary entry for the day he met her says “interview with madame the dauphine” (Goldstone, 252).

Conjugal Relations (or Lack Thereof)

When you realize that we have a severely inhibited 15-year-old groom, a terrified 14-year-old bride, neither of whom had any choice about this marriage whatsoever, it is perhaps not surprising that the wedding night was less than blissful.

We don’t have any first-hand accounts, obviously, but the entire court noted that Louis got up early next morning and went hunting as usual. He showed no further interest in his bride. That gave rise to lots of public press openly speculating about the dauphin’s sexual prowess (or lack thereof) which cannot have helped his confidence levels at all.

Some historians also call Marie Antoinette “frigid” and put blame on her (Hardman). “Frigid” is a word at which I am inclined to be annoyed. She was very young, very scared, very overwhelmed by all the attention, and as baffled as everyone else by Louis’s anti-social behavior. How much can you really expect from her?

Add to all that, she may well have felt insulted. An enormous amount of time and money (and let’s not forget the excruciating personal agony) had been poured into making her the loveliest and most desirable woman in the world. And yet, her Prince Charming was unmoved. He was to remain unmoved.

It was not long before her mother began sending letter after letter asking why she wasn’t pregnant yet. Marie Antoinette’s education may have been rushed, but she certainly knew enough history to remember than an unconsummated marriage is easy to annul. A childless wife is medium-easy to repudiate. And repudiation is for those who get lucky. The wives of Henry VIII of England offered plenty of instructive examples, and they are merely the most famous examples, not the only examples. If Marie Antoinette forgot any of these moral lessons, her mother was happy to remind her. As was the Austrian ambassador. Honestly, what did she think they had sent her into France for? She would be no good to Austria at all if she got sent back home. With or without her head.

Let’s just imagine Marie Antoinette’s confidence levels after all this and think about whether you think “frigid” is the most appropriate word.

If you want to assign blame, there is further proof (in a negative way), that it wasn’t her fault. The proof lies in the fact that your average young prince (no matter how charming he isn’t), generally has no trouble finding willing partners of whatever variety he prefers.

Versailles was a large community of people with virtually nothing to do except conduct extramarital affairs, spy on their neighbors’ extramarital affairs, and gossip. (Maybe I’m being a little overharsh here, but not a lot.)

Louis had no shortage of role models to show him how to betray his marriage vows, and no shortage of people who would be eager to report on it if he had. Yet he does not seem to have done so, not with any gender, not at any time. There’s no record of a mistress at all. Not even a one-night fling.

It is generally believed that both bride and groom were still virginal four years after the wedding when the old king died of smallpox.

Louis was now 19. Marie-Antoinette was 18. She is said to have said in a stricken voice “But we are too young to govern!” (Goldstone, 269).

Which was probably the most gentle way of saying what everyone else was also thinking.

Selected Sources

Fauchard, Pierre. Le chirurgien dentiste. France: Chez Jean Mariette, 1728. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Le_chirurgien_dentiste/BjBSAAAAcAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Faÿ, Bernard. Louis XVI, Ou, La Fin d’Un Monde. Translated by Patrick O’Brien, London, W.H. Allen, 1968.

Fraser, Antonia. Marie Antoinette : The Journey. New York, Ny, Anchor Books, 2002.

Hanley, Sarah. “Configuring the Authority of Queens in the French Monarchy, 1600s-1840s.” Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques 32, no. 2 (2006): 453–64. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41299380.

Hardman, John. Louis XVI. New Haven, Conn Yale Univ. Press, 1993.

—. Marie-Antoinette : The Making of a French Queen. New Haven, Yale University Press, 2019.

Hearsey, John E N. Marie Antoinette. Sphere Books, 1972.

Imbler, Sabrina. “Marie Antoinette’s Letters to Her Dear Swedish Count, Now Uncensored.” The New York Times, 1 Oct. 2021, http://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/01/science/marie-antoinette-letters.html.

Jefferson, Thomas. Autobiography of Thomas Jefferson, 1743-1790: Together with a Summary of the Chief Events in Jefferson’s Life. United Kingdom: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1914. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Autobiography_of_Thomas_Jefferson_1743_1/5lG7ISgjvr0C?hl=en&gbpv=0

Nancy Bazelon Goldstone. In the Shadow of the Empress : The Defiant Lives of Maria Theresa, Mother of Marie Antoinette, and Her Daughters. New York, Little, Brown And Company, 2021.

Padover, Saul Kussiel. The Life and Death of Louis XVI. D Appleton-Century Company, 1939.

Sanson, Henri. Memoirs of the Sansons, from Private Notes and Documents. 1689-1847. United Kingdom: Chatto and Windus, 1876. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Memoirs_of_the_Sansons_from_Private_Note/ZZdIAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjkstSj-aWFAxWEAHkGHYylC0AQiqUDegQIDRAG

Timms, Elizabeth Jane. “When Mozart Met Marie Antoinette?” Royal Central, 5 July 2020, royalcentral.co.uk/features/when-mozart-met-marie-antoinette-133508/.

My favorite portrait is the one with Marie in men’s clothes. But I really want to know the story behind that portrait.

Thanks for piquing my curiosity. You rock.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks!

LikeLike

[…] did not change much. It is quite clear that upper class women continued to use makeup. For Marie Antoinette, putting on her daily range was ceremonial and witnessed by a great crowd (Hearsey, 22). She had […]

LikeLike

[…] couple in a marriage arranged by their parents (see episode 2.5 on Catherine the Great and 12.9 on Marie Antoinette for other examples). But others swore that Arthur had led them to believe otherwise. And it […]

LikeLike

[…] noticed this especially when I covered Marie Antoinette, who some people say had ADHD, and her husband Louis, who some people say was autistic. In Marie […]

LikeLike