The islands of Hawaii are among the most isolated on earth. Somewhere in the neighborhood of 1000 CE (that date being much debated), the Polynesians arrived. Then they pretty much kept themselves to themselves until 1778, when the English Captain Cook stepped ashore, and that was the end of isolation.

It was also (ultimately) the end of Captain Cook. After what was really an unusual degree of mutual respect, a small dispute got ugly and the Hawaiians killed him. They were real sorry for it though, and they awarded his body their greatest honor: They baked it. Not to eat! No, no, of course not! They baked it because then it was easier to get the flesh off the bones, and it was the bones they would preserve and honor (Cook, introduction; Siler, xxii; Haley, 10). Captain Cook’s crew failed to appreciate the gesture.

The Hawaiians liked iron and the other metals brought by their new regular visitors. They also liked the written word. This was a thing they had never had before, but after missionaries created an alphabet that would work for them, Hawaiians became one of the most literate societies in the world (Siler, 11). Many Hawaiians also liked Christian message of the missionaries.

A High-Ranking Girl

Through all of this, Hawaii remained its own country, ruled by its own rulers (Siler, 13). That was the situation on September 2, 1838, when a high-ranking Hawaiian woman gave birth in a grass hut. The highest chiefess had an eye infection at the time. So the baby was named Lili’u Loluku Walania Kamaka’cha, which means Smarting Tearful Burning Pain Sore Eye (Siler, 7). Not exactly what I would have chosen as far as commemorative names go, but hey, it was a different culture.

Hawaiians had a strong tradition of adoption. There was nothing unusual about the fact that Lili’u’s parents gave her away to be raised by another couple of even higher rank (Siler, 7). Her new family baptized her and a few years later sent her to a boarding school on Oahu, run by Christian missionaries (Siler, 9). There she met her brother David for the first time, as he had been adopted by a different family (Siler, 11).

A Slowly Evolving Situation

No one expected Lili’u to be queen. Or David to be king. They weren’t that high status. But they were close enough that when Lili’u left school in 1855, her time was filled with court parties, balls, and other state functions (Siler, 30). While she was gadding about, the situation in Hawaii was rapidly evolving. On the one hand, Hawaiian land was becoming a hot commodity. When the American Civil War disrupted Louisiana’s sugar production, Americans needed another source. Sugar grows well in Hawaii (Siler, 33).

On the other hand, the Hawaiian population had been over 250,000 when Captain Cook arrived. But disease had ravished them. Not only were there diseases like measles, which killed large numbers, there were also diseases like gonorrhea, which didn’t kill a lot of folks, but did leave many of them sterile (Pirie, 76). Then there were the ones like syphilis which killed many and left survivors unlikely to have healthy children, a double whammy (Pirie, 77). As if that wasn’t enough, what youth Hawaii had were by no means immune to the pull of golden opportunities elsewhere. In the year 1850 alone, 4000 young men left to be sailors. That’s 12% of all working age males. Most of them never came back (Siler, 34).

As elsewhere in the world, the combination of native population collapse and an influx of foreign ready cash meant that foreigners were playing a greater and greater role in every aspect of society. Nowhere was this more startling to me than in the matter of high-ranking marriages. European royalty was all about keeping the bloodlines pure, but not so here. Occasionally there was a racist comment (in both directions), but it didn’t seem to stop anyone. Lili’u was encouraged to marry John Owen Dominis, a man from a prominent white family.

It was never a great marriage. After the wedding in 1862, Lili’u had to live with her mother-in-law, which was tense. She and John never had any children at their own. Lili’u kept busy with court functions and music and college classes and helping a Swedish scholar investigate Hawaiian oral history (Siler, 48).

In 1872, King Kamehameha V died without an heir. The legislature elected his cousin to be the new king. He lasted for only a year, and then he died without an heir. So another election. When David (Lili’u’s brother) won, riots broke out, and his very first official act was to call for American troops to help him maintain the peace (Siler, 59-60).

David took the throne under the name Kalākaua. He was married, but like so many others, he had no children. In 1877 he named his sister Lili’u as his heir and gave her the name Lili’uokalani, the first time that name had been used (Siler 77).

Crown Princess

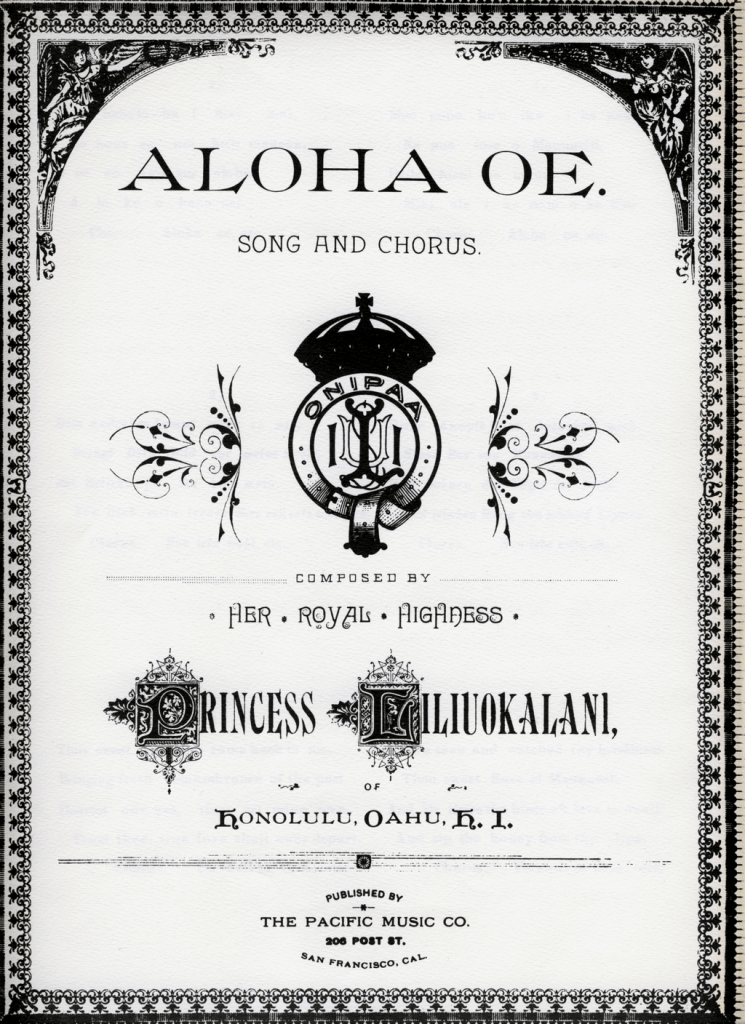

As Crown Princess, Lili’u took her first trip abroad. She went to California (Siler, 77). She also adopted a child over the objections of both her brother and her husband. She also composed a lot of music, including the most famous of her many songs, “Aloha Oe” (Siler, 78).

Here is a link to a recording by William Smith and Walter K. Kolomoku in 1915, which means Lili’u lived long enough that she might have heard it. Alternatively, you can listen to my recording of the first verse at the end of the episode.

Kalākaua, meanwhile, was borrowing money at an enormous rate. Most of the people with money to lend were Americans. Many Hawaiians began to feel they had a puppet king, beholden to his creditors.

In January 1881, the king called his sister to drop the big news: he was going to circumnavigate the globe! She would be regent. With oversight from a council, of course. Lili’u, age 42, said no: He would circumnavigate the globe, fine, and she would be regent, fine, but you can forget about that supervising council (Siler, 87). The king said, yeah, okay, sounds good.

Within days, he left. Just in time to miss the smallpox epidemic. As regent, Lili’u acted swiftly and decisively. She put travel bans and quarantines in place and called for a day of prayer. I’m sure that most of you listeners remember just how popular travel bans and quarantines are, but they were the only tools she had to fight a disease that even today we still do not have a cure for. The fact that you don’t know anyone who has died of smallpox (at least not within the last 44 years) is thanks to a vaccine and a global public health initiative.

The epidemic was back under control by August, just in time for David to come home (Siler, 88).

In 1887, Lili’u and her sister-in-law, Kalākaua’s wife, traveled to England for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. They met the Queen, who treated them with respect.

They also met the future Kaiser Wilhelm II who in later years would preside over Germany in World War I. He protested his seat assignment next to a woman he considered a Negro. Victoria was not amused, but rather than cause offense, she rearranged the seating, assigning the Hawaiian queen and crown princess to her own sons, the Prince of Wales and the Duke of Edinburgh (Haley, chapter 16). Lili’u did not mention this incident in her memoirs. I hope that means missed the kerfuffle.

She also missed the kerfuffle back at home, where Kalākaua was in trouble. Many in the white merchant class were deeply concerned about the stability of his government. Some formed a Committee of Public Safety, which is an ominous name, historically speaking. The committee drafted a new constitution, presented it to the king for his signature, making sure he knew that the alternative was violence. He signed. What became known as the Bayonet Constitution, had some curious rules, like the fact that you didn’t have to be a citizen to vote for representatives to the upper legislature, but you did have to meet income and property thresholds. In other words, it was mostly white businessmen who could afford it. Also, the king no longer had an absolute veto, nor could he act without consent of his cabinet, nor could he dismiss his cabinet. The king was now truly a figurehead. (Siler, 145-146).

More than one person suggested Lili’u would make a better monarch. Perhaps that was in his mind when he appointed her regent and went abroad again, ostensibly to campaign for better trade relations with the US. He died in California in 1891 (Siler, 172).

A Queen’s Role

On the very day this news reached Hawaii, before the body had even had time to come ashore, the men of the council gathered by Lili’u. In her own words “a trap was sprung upon me by those who stood waiting as a wild beast watches for his prey” (Lili’uokalani, 209). They wanted her to swear an oath to the Bayonet Constitution. She said, couldn’t that wait until after the funeral? They said no. Dazed and confused, she swore the oath (Lili’uokalani, 209). More than that, the chief justice shook her hand and calmly informed her that if any member of her cabinet should propose anything to her, she should say yes (Lili’uokalani, 210), which is pretty indicative of what these men thought her role was going to be.

Lili’u thought differently. One day after the mourning period, she called in the cabinet and asked for their resignations. They said the constitution said she couldn’t dismiss them. She said the constitution said she couldn’t dismiss her cabinet. These men were never her cabinet in the first place. New monarch, new cabinet. The Supreme Court supported her (Siler, 180; Lili’u, 218).

Changes in the US tariffs were wreaking havoc on the value of sugar and the government still had to borrow money just to function. The legislature considered two proposals to fix that: one was a lottery bill and one was an opium bill. Both of those had their moral critics, but the main point was that they would also raise revenue, which was rather desperately needed. The legislature passed them and Lili’u signed.

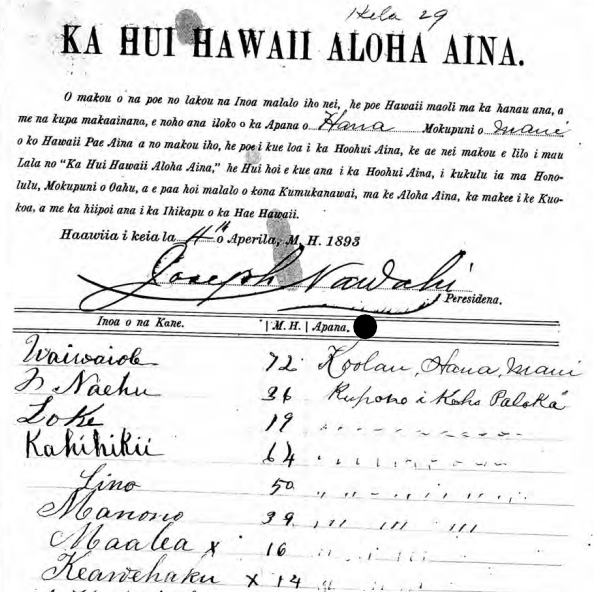

She also worked on a new constitution. Native Hawaiians hated the Bayonet Constitution and for good reason. According to Lili’u’s own account, by 1892 she had received petitions for a new constitution signed by two-thirds of her registered voters. In her mind, she could not ignore such a mandate (Lili’uokalani, 231).

I am sorry to say that in her proposed constitution, voters still had to be male (Article 62), but there wasn’t a racial requirement and the property requirements were lower. It also gave Lili’u many of the powers the Bayonet Constitution had taken from her brother. To be clear, this constitution expanded both the voting power of the people and her own power. Which one of those two things you stress makes a big difference in whether this is a beneficent and enlightened move or a blatant power grab.

In December 1892, Lili’u tried to get her new constitution through the legislature. The bill failed. Those in the legislature were those benefiting from the Bayonet Constitution (Siler, 201).

Lili’u was not going to back down where she believed herself right. In January she tried another and far more dubious method: royal fiat. She called for a big crowd. All were waiting expectantly for her declaration just after the signing ceremony. She had not counted on her cabinet refusing to sign. They had helped her write the thing, but they weren’t on board with the royal fiat idea (Siler, 203). That also made it look like a power grab.

Furious, Lili’u had to announce to her crowd that there was no new constitution, but she hoped there would be in a few more days. Her supporters were disappointed. Her opponents were worried. Both sides were potentially about to become violent.

The Coup

The American minister, John L Stevens, requested the captain of the USS Boston to send troops ashore to protect American lives and property. Yes, that’s right, the top American diplomat authorized the landing of heavily armed American soldiers into a foreign country without the permission of said country’s government (Siler, 213).

There was worse to come. Lili’u’s opponents talked to Sanford Dole (he of the Dole pineapple you have probably eaten). They convinced him to accept the presidency of a new provisional government. Their proclamation abolished the monarchy because she had clearly violated her oath to support the Bayonet Constitution. Also lotteries and opium were immoral. She was a despot, through and through.

On the same day, John L Stevens recognized the new provisional government. Yes, that’s right, the top American diplomat spent less than a day considering whether a foreign sovereign was so far in the wrong that a coup deserved US approval. American troops were already encamped at the capital.

As I said last week about Lakshmibai, this was the point where Cleopatra, Boudica, Zenobia would have raised an army. Lili’u’s forces were already stronger than the Provisional Government’s. But her ministers advised her against provoking bloodshed. So far the coup had caused only one injury and zero deaths (Siler, 217).

Besides the laudable desire to save lives, there was a historical reason for thinking violence was unnecessary. Back in 1843, an overreaching British captain had disobeyed orders and seized Hawaii for Britain. His superiors were not pleased and after five months the kingdom was restored to the Hawaiians (Haley, 131-145).

So Lili’u agreed to yield, but her statement was carefully worded. She did not surrender to the Provisional Government. Instead, she yielded directly to the United States, with protest. (Siler, 221). The hope was that when news reached Washington D.C., the American government under President Grover Cleveland would do the right thing: namely withdraw the troops and recall their overreaching diplomat.

The modern cynic might question just how likely an American government was to take that approach. But even the modern cynic must allow that it was far more likely while no American blood had been spilled. Fighting back might well backfire.

The United States Dithers

Indeed, the early signs were hopeful. President Cleveland sent Commissioner James Blount to investigate. Blount ordered the US troops to withdraw, the American flag to come down, and Minister John L Stevens to go home (Siler, 332). His report was firmly on Lili’u’s side. A later report said just the opposite, but that was still to come.

Based on Blount’s report, the US sent a new minister: Albert S. Willis, whose first assignment was to apologize for Stevens’s “reprehensible conduct.” Those are the official words. The US was fully prepared to undo the “flagrant wrong.” More official words.

In return, Willis told Lili’u the US wanted full amnesty for the members of the Provisional Government.

According to Lili’u, she responded that she would have to consult her privy council because legally, treason was punishable by death. She personally preferred banishment, after confiscating their property to pay government debts. Not from revenge, but from simple recognition that if she let them stay in Hawaii, they would only continue to cause trouble. She would consult her ministers on what would be best (Lili’uokalani, 246).

According to Willis, what she said was “My decision would be, as the law directs, that such persons should be beheaded and their property confiscated to the government (Siler, 240).

Quite a difference in tone there. And you cannot blame a translator. Lili’u spoke very good English. There was no translator. She eventually signed Willis’s notes on their interview, but she says she wasn’t allowed to read them. They were read out to her and she signed believing it said something different.

It is a classic he said, she said. Like every other such case, it’s impossible to resolve. However, one author has pointed out that even if Lili’u’s anger did flare up, it’s unlikely that she used the word beheaded. Traditional Hawaiian executions were done by strangulation, clubbing, or being thrown off a cliff (Haley, 311).

Willis dithered about this unexpected hitch, and eventually Lili’u caved. She agreed to full amnesty in December, almost a year after the coup. The following day Willis told the Provisional Government to stand down (Siler, 293). The Provisional Government said the US should mind its own business.

That was stalemate. Willis had no mandate to fight a war on Lili’u’s behalf. Back in DC, the politicians were locked in partisan gridlock.

A Prisoner

Lili’u’s supporters plotted uprisings. It is true that some of her supporters were white and some were Americans. But on balance they weren’t, and the Provisional Government responded with rules like native Hawaiians can’t carry firearms or gather in groups. They made a new constitution that disenfranchised so many Hawaiians that Willis said “it is certainly a novelty in governmental history—a country without a citizenship” (Siler, 253).

Lili’u was arrested for the uprisings, which she may or may not have known about. She says not, but even I find her denials to feel just a little disingenuous. She was given a suite at the palace (that is to say, her palace).

She was allowed no newspapers and all visitors had to be approved (Siler, 262). After a few days she was given abdication papers. She was told that if she did not sign them, the executions of her supporters would begin (Lili’uokalani, 273-274).

Defeated, she asked what name she should use to sign, and they said Lili’uokalani Dominis.

Her regnal name was just Lili’uokalani. As a young bride in a white world, her name had been Lydia Dominis. Among friends she went by Lili’u. When she signed her abdication as Lili’uokalani Dominis, it was the first time those two names had been put together. In her mind, there was no such person (Lili’uokalani, 276; Siler, 297).

After eight months of imprisonment and a legally questionable trial that found her guilty, Lili’u was allowed to go to her family home. President Sanford Dole graciously granted her a pardon.

One Last Effort

Lili’u decided to go to the US, ostensibly to visit relatives, but also to see if the US couldn’t be persuaded to do just a little bit more about reining in their citizens.

It was for the purpose of publicity that she wrote her autobiography and published a collection of songs. Many Americans were quite sympathetic. It was just her bad luck that they were published in the year 1898, the same year as the Spanish-American War. Hawaii was the only place in the Pacific where a naval vessel could resupply on its way to the Spanish-held Philippines. DC had no partisan gridlock about strategically important harbors. They passed an annexation bill with ease, and President Dole did not tell the US to mind its own business.

Grover Cleveland, who was no longer president and had refused to annex Hawaii when he was, said “Hawaii is ours… as I contemplate the means used to complete the outrage, I am ashamed of the whole affair” (Siler, 285).

It’s easy to second guess, but in hindsight there are two crucial moments where you do have to wonder what would have happened if Lili’uokalani had acted differently. What if she had not tried to impose the new constitution by fiat? Or if she had not mentioned the death penalty? She had no shortage of provocation, but politics is the art of the possible. Both moments were used to paint her as a power-hungry and criminal tyrant who needed removal for Hawaii’s own good. Advocates of this view are still publishing today (Fein).

A sad Lili’u returned home shortly after the US decision. The United States did her the honor of including her in the formal ceremony for the annexation of her country. Her invitation was addressed to Mrs. John Owen Dominis (Siler, 287). She did not attend.

Lili’u lived until 1917, by which point she had long since been an American citizen. Her later years involved a lot of legal wrangling over property that was maybe hers or maybe the government’s. She left what she had to a trust that helps destitute children (Siler, 295).

For the record, in 1993, 100 years after the coup, the US Congress and President Bill Clinton passed an Apology Resolution, which acknowledged the role of US agents and citizens in the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii.

Selected Sources

Akaka, Daniel K. “S.J.Res.19 – 103rd Congress (1993-1994): A Joint Resolution to Acknowledge the 100th Anniversary of the January 17, 1893 Overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii, and to Offer an Apology to Native Hawaiians on Behalf of the United States for the Overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii.” Www.congress.gov, 23 Nov. 1993, http://www.congress.gov/bill/103rd-congress/senate-joint-resolution/19.

Cook, James. “Captain Cook’s Journal during the First Voyage Round the World.” Gutenberg.org, 2012, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/8106/8106-h/8106-h.htm.

Fein, Bruce. Hawaii Divided against Itself Cannot Stand. 2005.

https://www.angelfire.com/hi5/bigfiles3/AkakaHawaiiDividedFeinJune2005.pdf.

Haley, James L. Captive Paradise : A History of Hawaiʻi. New York, N.Y., St. Martin’s Press, 2014.

“Is Hawaii a Part of Oceania or North America?” WorldAtlas, 12 Jan. 2018, http://www.worldatlas.com/articles/is-hawaii-a-part-of-oceania-or-north-america.html#:~:text=However%2C%20unlike%20Hawaii%2C%20Alaska%20is. Accessed 10 May 2024.

“Kingdom of Hawaii Draft Constitution of January 14, 1893.” Www.hawaii-Nation.org, 1892, http://www.hawaii-nation.org/constitution-1893.html.

Pirie, Peter. “The Consequences of Cook’s Hawaiian Contacts on the Local Population.” Conference Paper for the 3rd Annual Pacific Islands Studies Conference, 1978, core.ac.uk/download/pdf/5103891.pdf. Accessed 10 May 2024.

Oh– Aloha-oe was beautiful! Who was your duet partner?

LikeLike

Thank you! It’s all just me singing and playing. I layered the tracks to make the harmony.

LikeLike

Oooooh, fancy. 😀

LikeLike