Within my lifetime, there has been a lot of talk on the troubling concept of telling any woman what shape her body ought to be. It’s arguable whether there has been any effect from all the talk, but I think people are at least somewhat aware of the damage caused by holding girls and women to an impossible beauty standard. We’re less aware of how long this has been going on. Mass media (and especially social media) get the blame and no doubt they have amplified the effects, but women have been chasing impossible beauty standards for at least hundreds of years and probably for thousands of years.

The particular standard of beauty they chased have changed a lot over time, as you’ll see throughout this series. The average height of women varies by only 10% worldwide. But the average body mass varies by 50% (Ruff, 211), which leaves us with a lot of possible variations for fat distribution on the same basic skeletal frame. The fat distribution that we currently idealize has not always been the prized one. In fact, as I did the research for this episode, I began to feel that no matter what body shape you have, there might be a historical time period where you are gorgeous, just as you are, no need for diets or surgery or concealing clothes. Listen up and let’s see if you can find your time period. No promises you’ll find it, but I’m hopeful.

A couple more caveats: I’m focusing on the Western world in this episode because I just don’t have the sources to talk about anyone else. Nonwestern women will come into the series eventually, though, so just hold that thought for a few weeks.

In the earliest time periods, I’ll be using art because there aren’t any written records, and I’m going to admit straight off that I’m making a major assumption. My assumption is that the artistic depictions of women are supposed to be beautiful. We actually don’t know that in most cases. Not unless the artwork in question comes clearly labeled as Goddess of Beauty.

Certainly it is possible for art to depict hags and sometimes it does. Also it is possible for art to depict realism, without attempting beauty. And it is possible for art to go for shock, horror, or just plain weird. Visit any modern art museum, and you’ll see what I mean.

But I think it is safe to say that most art throughout the ages was intended to be beautiful. There’s a reason why the weirdest of the weird modern art gets a far more limited audience than the older masters. Most of us prefer looking at beauty, and I’m going to assume that holds true for people in the past.

Prehistoric Beauties

If we take all those assumptions, then the ideal female body size in prehistoric times was large. I originally included a written description here of the Venus of Willendorf, a statue in the neighborhood of 30,000 years old. But now I am going to direct you to look at the picture:

I cut the written description because after a discussion with my beta listener, I have realized that it is very difficult to give a physical description without sounding judgmental and rude. I don’t mean to sound that way. But I have lived all my life in a culture with nearly the opposite beauty standard, so even a very technical description of obesity comes with a whole lot of baggage and a whole lot of hurt. (Please keep that in mind throughout this episode. The descriptions are not really what sting, I hope. What stings is a modern culture that tells us there is something wrong with looking that way.)

This Venus is not alone. They come from a variety of prehistoric cultures, and you’ll see no flat stomachs and no thigh gaps among them.

EnriqueTabone, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Ramessos – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Petr Novák, Wikipedia

Logically, it makes sense. In a world where food was an uncertain resource, obesity was a sign of abundance. There is nothing more beautiful than the thought of having more than you really need.

Nowadays, some of us (certain idiots on social media aside) know that there is a lot more to losing weight than just calories in vs. calories out. However, there is no denying that people who are starving do tend to get thinner than they were, and since that was a very real possibility in prehistoric times, people were familiar with that phenomenon. By the way, I do not recommend starving yourself as a diet plan.

I do not know whether prehistoric girls had body image problems, but if they did, art history suggests that their problem would have been how to pack on the pounds, not how to trim them off.

Egyptian Beauties

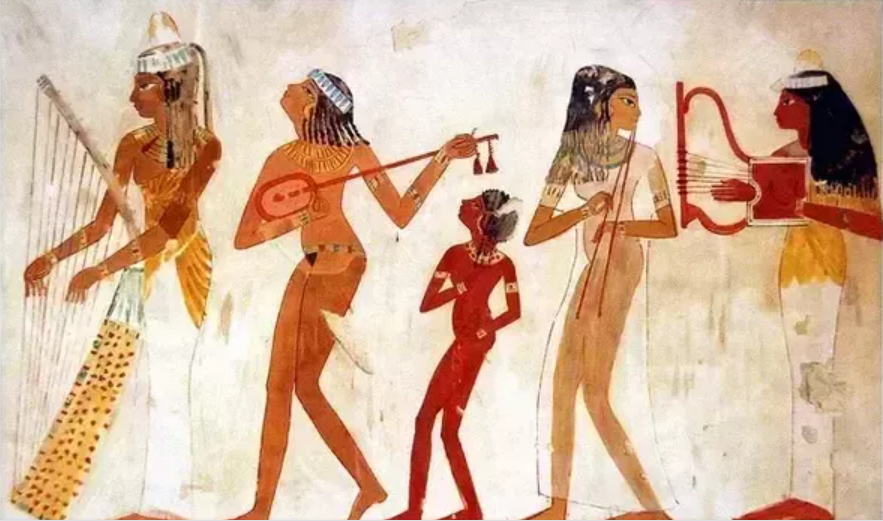

All that is going to change with the advent of settled agricultural communities. Food sources became more secure (at least if you were a member of the upper classes) and the artistic depiction of beautiful women changes dramatically. Egyptian women are depicted as slender and elegant. Later on, we’re going to have a little trouble distinguishing the shape of the woman versus the shape of her clothing, but that’s not a problem here, because Egyptian women often aren’t wearing any clothing. Or when they do, it’s sometimes so thin as to be totally sheer.

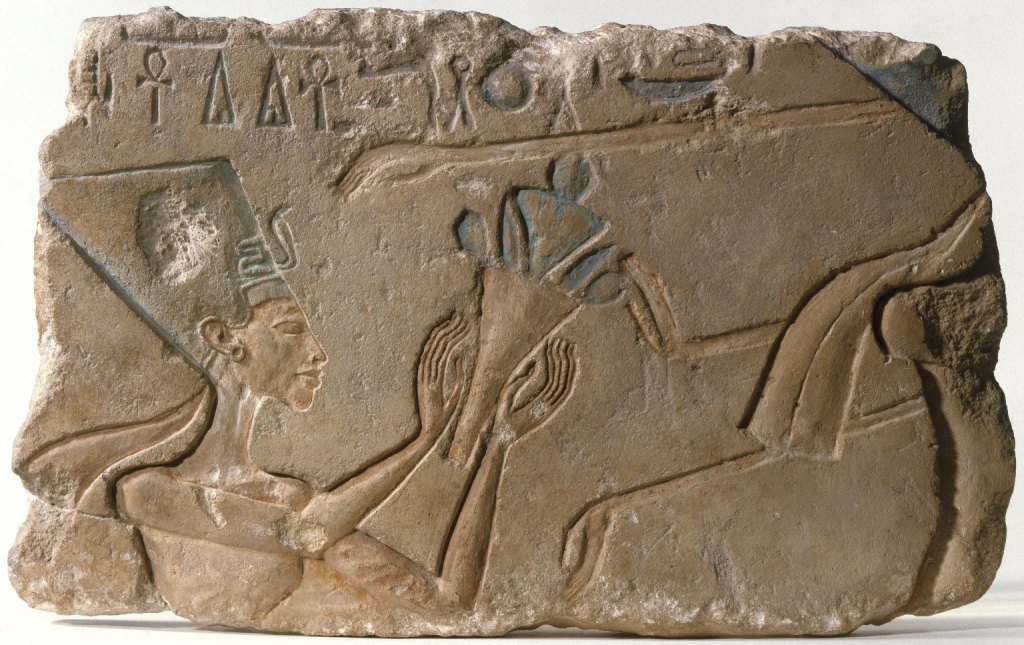

The name Nefertiti actually means “the beautiful one is here,” which is about as clear a label as art ever comes with. When I think of Nefertiti, I think of the famous sculpture of her head, and it is very beautiful with a long, graceful neck. But it’s only a head. There is no hint of the body shape below it.

Fortunately for us, Nefertiti’s time (1370-1330 BCE) was a golden age of art. We have multiple depictions of her and there’s a reason why that particular bust is so famous: the other depictions of her are not quite so beautiful to modern eyes.

Some of them show her with sunken cheeks, pointy chin, wrinkle lines, and an oddly lengthened shape that looks slightly alien. She’s basically the polar opposite of the Venus figurines: there is nothing round about her. Even her breasts are quite small and firm. Since her entire family is depicted in the same way, many art historians have searched for a genetic condition that would explain their very odd appearance. While others have countered by saying that it’s art, and there’s no reason to assume it was realistic art. Probably Nefertiti didn’t really look like that (Arnold, 19).

Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 71.89. Creative Commons

But I would say the usual technique when doing portraits of powerful people is to flatter them by making them more beautiful than they really are. Not less. Which suggests (but does not prove) that a long, angular body was the ideal, and we can only wonder how hard Egyptian women worked trying to achieve it. Egypt lasted a long time, and not all of their depictions of women are so strange. But they aren’t Venus figurines. They very much tend to have small breasts, slender body, maybe a slightly protruding belly. No more than that (Arnold, 28, 57).

Greek and Roman Beauties

When we move into ancient Greece, things get murkier. The Greeks loved to portray the male nude, but the female nude, not as much. For women, they preferred the wet drapery look (Paglia, 5). Nevertheless, the draperies (unlike later clothes) are not so concealing that we can’t guess at the shape beneath, and it is neither round and large like the prehistoric Venuses, nor long and angular like Nefertiti. The two most famous are the Venus de Milo (c. 150 BCE) and the Winged Victory of Samothrace (c. 200 BCE). They are definitely the ideal of beauty, since they both come clearly labeled as goddesses, and goddesses of good things. They both look solid, fit, and a little bit muscular. They’re strong. I like them. That is the body type I wish I had, though I’m not saying I do. On the other hand, I have the proper number of heads and arms. They come up a little short in that respect.

Romans spent a while copying the Greeks, so the differences are hard for an amateur like me to sort out. And actually many of our Greek statues are really Roman copies of Greek statues. The Romans also have busts of women that are very realistic: wrinkles, double chins, and all (Paglia, 5), but the goddesses of beauty do not get portrayed like that, so I don’t think that was the goal.

Medieval Beauties

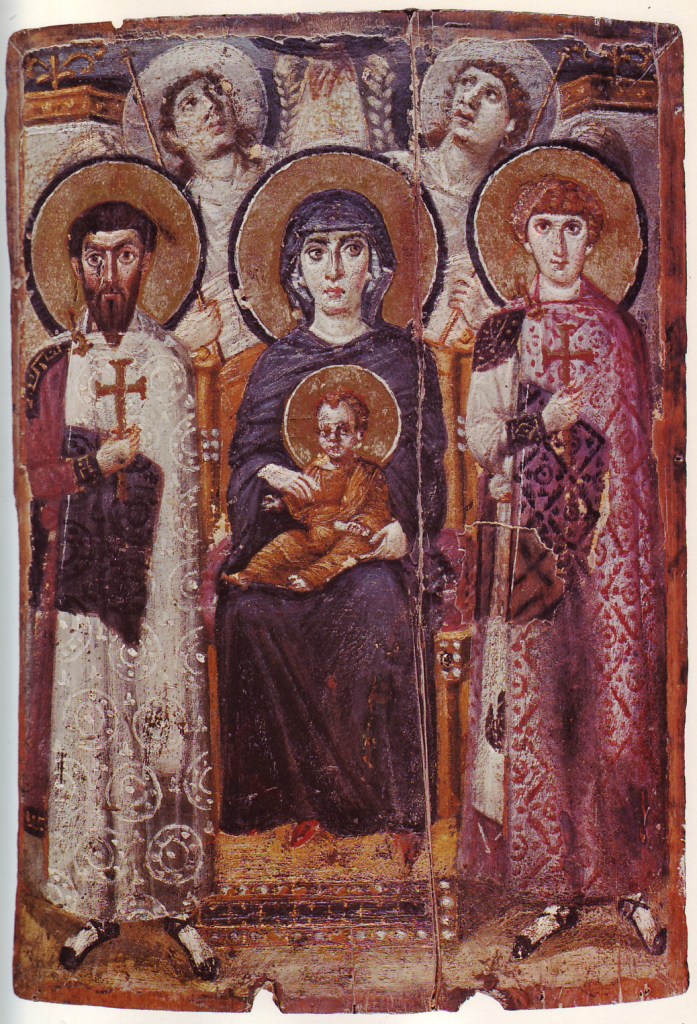

And then we get to the Middle Ages and this whole project falls apart because the primary patron of art in the West was the Church and pictures of naked or semi-naked women was not their thing. What women there are, don’t have much shape. Their clothes seem designed to conceal the idea that they had any sinful shape down there at all. Often there is little to distinguish them from the men.

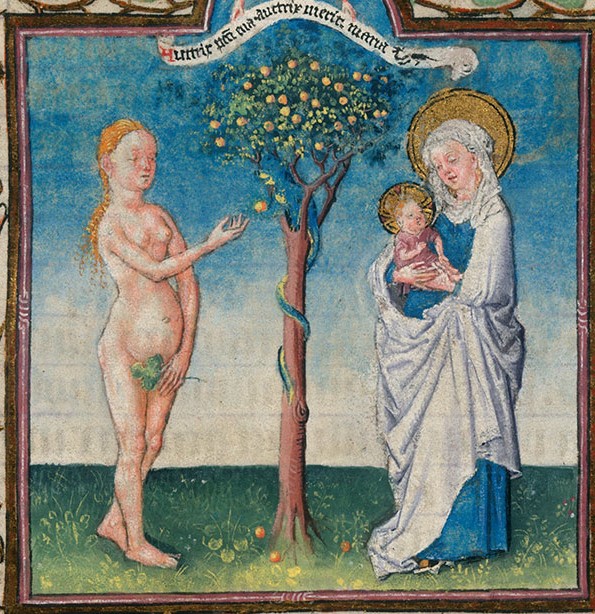

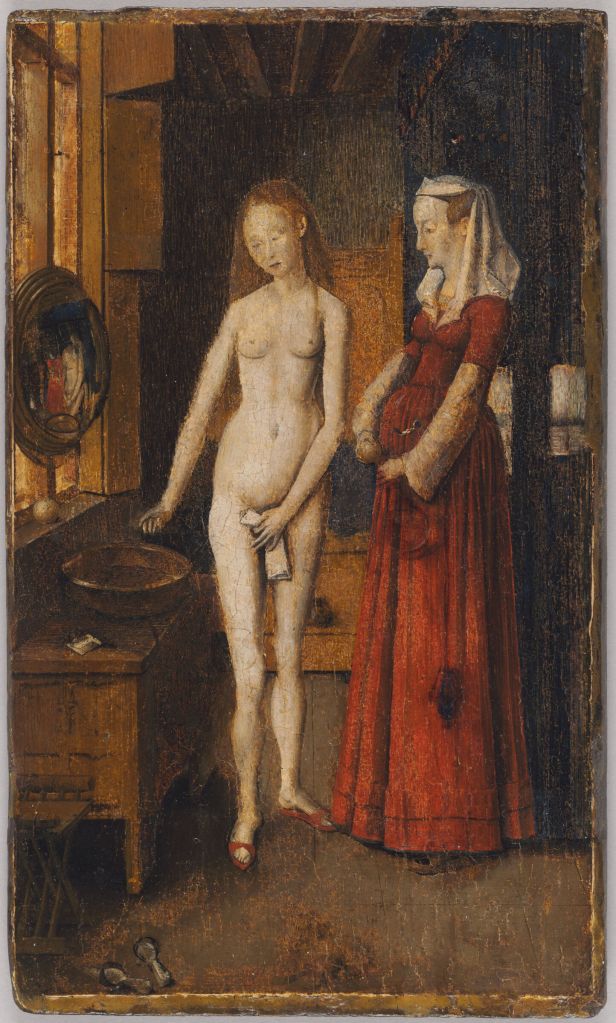

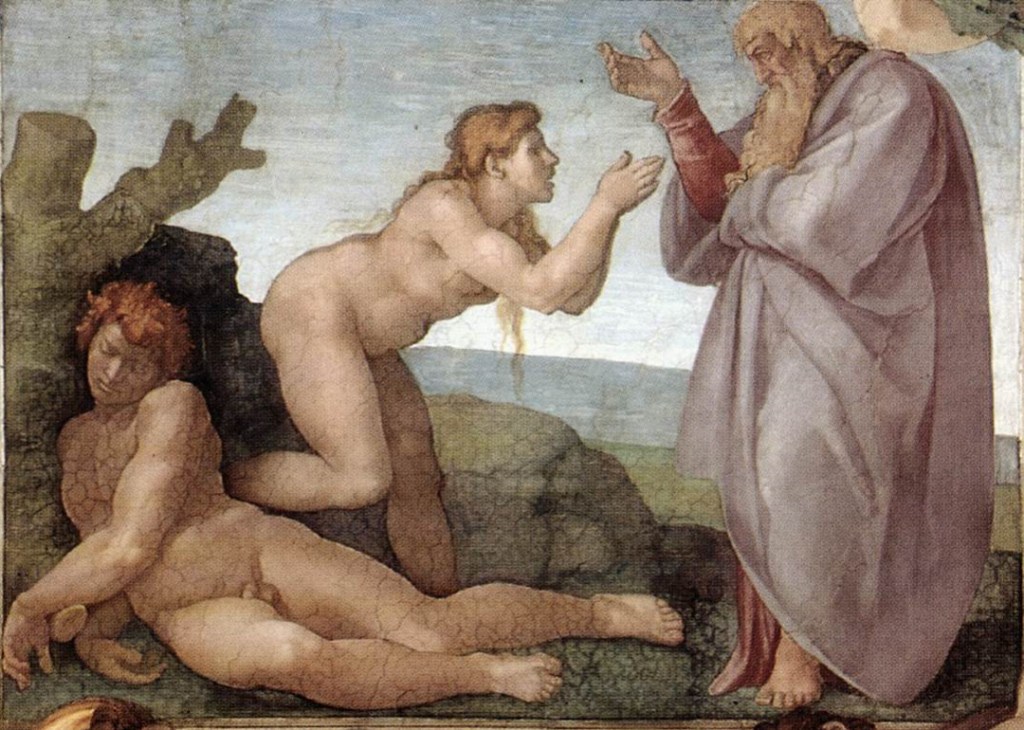

There are two major exceptions to this whole no-naked-women rule. You could depict Eve. It’s straight from the Bible that Eve hasn’t got clothes, so that makes that picture of a naked woman religious. And to a lesser extent you could do witches naked because they were about to be punished for their sins. Eve wasn’t much more than a step above a witch according to some theologians, so maybe that’s just one exception.

I have no doubt that all the shapeless Marys were the real personification of beauty, as well as all that is holy. But these lesser women surely weren’t considered repulsive or they wouldn’t have offered any temptation, right? My guess is that if you wanted to look good to a convent or a prospective mother-in-law you emulated Mary. If you wanted to look good to a man, you edged toward Eve, and let me tell you that is not shapeless. No, if your body is distinctly pear shaped, then the Middle Ages was your time period (Janega).

Now I admit that all my examples of this are from the High Middle Ages (the later part of the period). There’s just a lot less art that survives from the early period.

My oldest picture is from the stained glass on the Chartres Cathedral (1200s), and the hips are hard to see, as Eve is seated, but that belly isn’t flat. And her breasts make me wonder if the celibate monk who created the image was more familiar with a cows than he was with women. Let’s just say if that was supposed to be realistic, he’s flunking art class.

However, the remaining pictures are from the next two centuries and they show that breasts were small, high, and rather far apart. Cleavage wasn’t the goal. Down below, there’s a lengthy torso before a protruding belly that looks like it might be pregnant (but isn’t, because Eve definitely isn’t pregnant during her naked phase, the Bible’s clear on that). Rounded hips finish out that nice pear shape.

Wikimedia Commons

Once you know this body shape was beautiful, you can see it even under the clothed ladies of the High Middle Ages. They have a curious S-shape that sometimes looks like they are slumping or even thrusting their hips forward. That’s because a flat stomach was not the goal. A protruding belly was (Janega).

Renaissance and Baroque Beauties

By the Renaissance, the fear of a naked female body went completely out the window, and things get easier for us. Renaissance and Baroque artists were all out to celebrate the glory of God’s very physical creations and that certainly included the female body. There are plenty of nudes.

Van Eyck and Botticelli were on the early end, overlapping with some of the medieval art I just talked about, and their female nudes still retain some elements of the late medieval pear shape.

(this is a later copy of the work)

Harvard Art Museum

But from Michelangelo and on through Rembrandt, the women portrayed are full-figured with lots of fleshiness. In the words of Meghan Trainor, they ain’t no size two. In fact, I would venture to say that most of them would be shopping in the plus sizes. They remind me of the plus-size models that many clothing companies now use. They are beautiful and well-proportioned, but they don’t leave you wondering whether they’ve ever eaten a solid meal. Pleasantly plump was good.

And FYI, the same is true for women painted by female painters like Artemisia Gentileschi (episode 10.3).

Waist-to-Hip Ratio

What is about to change is the waist. It starts getting smaller. I will be talking more about the ways and means of achieving that next week, but this is where it begins.

You may have noticed that we are now thousands of years into art history and one body shape I have not even mentioned is the hourglass. There are lots of modern sources out there which assure me that the hourglass figure is universally the most attractive, across all cultures and times. Beauty is not in the eye of the beholder, it’s in the Waist-to-Hip Ratio (Singh). This is a real thing. Scientific papers even have an acronym for it: WHR.

This idea pops up in multiple of my sources (Riordan, Singh, Steele), but as far as I can tell this idea is traceable to one evolutionary psychologist, and I bet I don’t need to tell you what gender he was. However, I am pleased to say that it’s not just me saying it’s a bunch of garbage. I’ve got other sources on my side (Bovet, Paglia, Janega).

The narrow waist obsession began in the 1500s and gradually intensified. It’s easiest to see when the women are clothed because the hips are often artificially enlarged, while the waist is artificially narrowed. Even when the waist isn’t artificially narrowed, the mere fact that the hips are huge, makes the waist look small by comparison.

For the top half of the hourglass, it isn’t always a matter of enlarging the bust. Far from it, the breasts are sometimes bound and obscured and hardly noticeable on the long torso moving up and out, sometimes in a very angular triangle. In many cases, the real top of that hourglass is the shoulders and arms. Not always, but sometimes. The fashions change.

Since all this is artificially created, it’s not as obvious in the nudes. But it is there. One study of artistic beauties across the ages found that the WHR was more or less constant in the ancient world. Then from 1500 it started decreasing. In modern times, the study added in Playboy models and beauty pageant winners to the data set, and they found that the WHR kept decreasing until 1960s, when it paused or possibly even slightly turned around (Bovet).

19th Century Beauties

The late 18ᵗʰ and early 19ᵗʰ century had a brief vogue withgoing for the natural look. Well, sort of natural. The dresses you’ve seen in Jane Austen movies did plenty of bust modification, but since they fall pretty-much straight from just under the bust, we are not emphasizing that not-so-universal waist-to-hip ratio. It is not an hourglass.

However, that was brief and then we are right back to very, very artificial, and yes, hourglass in the 19th century what with corsets and various types of hoop skirts, crinolines, and bustles, all distorting and concealing a woman’s shape.

The 19th century also saw the rise of a brand-new vocabulary for telling a woman her shape was all wrong, and that was the vocabulary of science. Beauty was nothing new, and nor was the idea that certain body types would be better at motherhood, which is not a trivial consideration in a world where the primary purpose of marriage was to produce children. Now scientists could frame it all in terms of evolution and what is best for the propagation of the species. No surprise that their conclusions led them to exactly what their culture had already decided for them: white women are the best because they have the biggest hips and the fullest breasts. That’s not me saying that. It’s 19th century scientists saying it. Here’s a direct quote from Havelock Ellis, a leading medical doctor:

“The women of several Central African peoples, for instance, when viewed from behind, can scarcely be distinguished from men; even Arab women … show nothing of the globular fulness of the well-developed European woman. In some of the dark races [the pelvis] is ape-like in its narrowness and small capacity, in the highest European races it becomes a sexual distinction which immediately strikes the eyes and can scarcely be effaced … It is at once the proof of high evolution and the promise of capable maternity.”

(Ellis, 54)

This is wrong on so many levels, I don’t even know where to start: racism, cherry-picking the data, unclear terminology, lack of sources, etc. But for today let’s just focus on the fact that he was telling all women (including European women who might just happen to be naturally thin and small) that the body shape they were going for was “globular fullness.” I recommend against trying that out as a compliment nowadays, regardless of what race a woman happens to be, but it was right in line with the fashions of the day during Ellis’s time. He seems stunningly unaware that globular fullness was not chosen by natural selection. It was created by the corset. Again, more on that next week.

20th Century Beauties

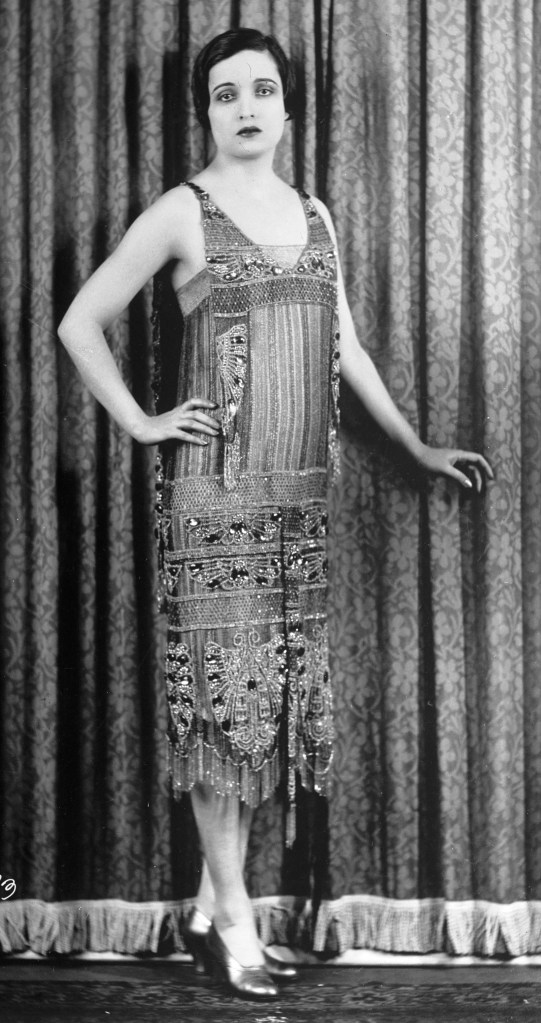

By the first few decades of the 20th century, the artistic nudes are no longer any help at all. The major artists had gone cubist or surreal or expressionist or art deco. Let me tell you there are some pretty weird body shapes out there, but I don’t think any living, breathing woman was trying to achieve that look. Or at least I hope not. But by now women had actresses, models, advertising, and beauty pageant winners to show them what they should look like.

In 1921, the very first Miss America was 16-year-old old Margaret Gorman, and her measurements were 30-25-32. Not a perfect hourglass, but not far off either. Also, small. All of this was unconcealed because the pageant was specifically advertised as a parade of “bathing beauties.” It’s true enough that the bathing suit was probably quite modest by modern standards, but it wasn’t any corset and hoop skirt. Her basic shape was reasonably visible.

Margaret was praised in the New York Times by no less a person than the president of the American Federation of Labor, who said, “She represents the type of womanhood America needs — strong, red blooded, able to shoulder the responsibilities of homemaking and motherhood. It is in her type that the hope of the country rests” (American Experience).

The pageant was judged solely on appearance, so winning didn’t actually say anything whatsoever about Margaret Gorman’s strength or fitness for homemaking or motherhood or anything else. But it was neither the first nor the last time that a woman’s worth was reduced to beauty alone. What was different was the age of mass media. This pageant was widely publicized, allowing women to compare their appearance not just with the other women of their own small community, but also with national beauty pageant winners. Is it surprising that so many of them felt they were failing?

The 1920s also brought us the androgynous look. Women may or may not have actually had an hourglass figure, but they weren’t flaunting it if they did. No, they bound up their breasts instead for a straight up, straight down look. The sexual emphasis was no longer on the waist and not yet on the bust. Instead you were flaunting your legs, which had only recently been uncovered, and the face which was now sporting makeup (Riordan, 66). However, since the body shape was really supposed to be flat all the way down, it wouldn’t do to be rounder around the middle, and women started worrying quite a bit about being thin, which had not necessarily been a goal for their mothers, not even the ones in corsets. For many women, straight up, straight down, was just as unnatural as the 19ᵗʰ century hourglass look.

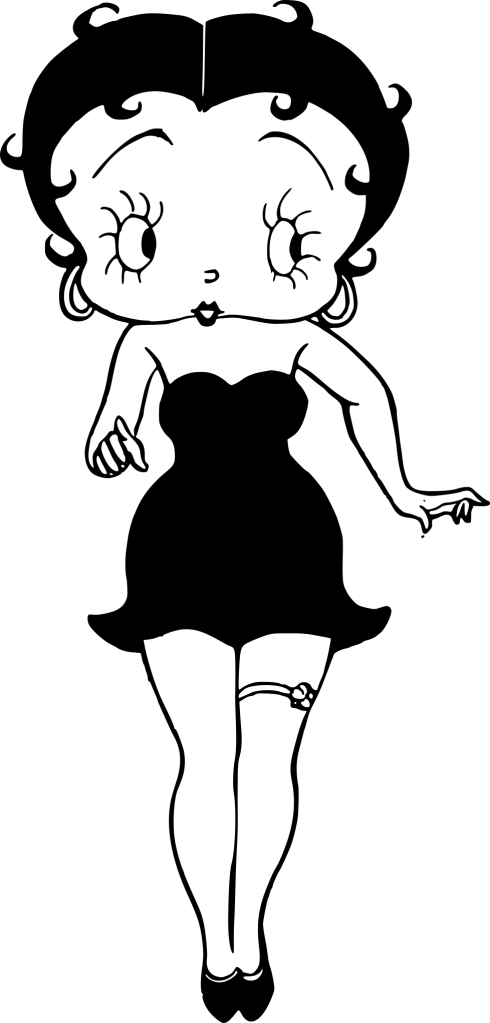

But every action has a reaction and by the 1940s, beauty had shifted as far as possible in the opposite direction. When Betty Grable achieved fame as a pin-up girl, we were back to hourglass. Only this time, it’s not so obviously artificial because she’s not in a hoop skirt. It’s not hard to see her shape. She’s full breasted (no more binding those up, let’s pad it up more like, top heavy is good). She also has a small waist and nice round hips. Betty Boop, the cartoon character, was all that and more so. Marilyn Monroe was that in the 1950s.

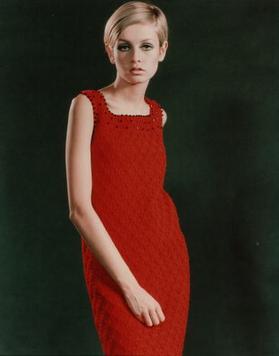

But Audrey Hepburn (who also achieved fame in the 1950s) was something different. Technically, Audrey was an hourglass figure, if the Internet is correct about her measurements. She was just a very, very thin hourglass, with a 20-inch waist. She wasn’t voluptuous. She was delicate and waiflike. So was Twiggy, the 1960s international supermodel. And there we were, back to the 1920s androgynous look, which most women will struggle to achieve, even with artificial help.

However there was a major, major difference. Feminists and the whole culture of the times had championed comfort and freedom of movement, neither of which were priorities for some of our foremothers. Women had gotten rid of the corset and the binding of the breasts. Sometimes they’d even burned their bras. Now you were supposed to look fabulous without such artificial aids. You were supposed to look fabulous in increasingly tiny swimsuits, which left absolutely no room for your undergarments to obscure or reshape anything.

In other words, it was no longer enough to look a certain shape. You had to actually be a certain shape. Or in the words of one of my sources “the corset was replaced by an invisible psychological corset” (Bruna, 238).

Thus far, thinness has remained a lasting beauty standard, and millions of women spend a great deal of money, time, and health trying to achieve it. Just think how baffled our prehistoric foremothers would have been, the ones who envied the Venus figurines for their rolls of fat. I will be going into a great deal more detail about all the ways women have tried to achieve the ideal in the upcoming weeks. But for today it’s just interesting to think about how much things have changed, I’m pretty sure that for many women, no matter the time period, the truly ideal body shape is whichever one you don’t have.

Selected Sources

Alex. “How Audrey Hepburn Changed the Way Hollywood Looked at Women.” Medium, 29 Dec. 2019, medium.com/@AAW98/how-audrey-hepburn-changed-the-way-hollywood-looked-at-women-ddbba48f4cbb.

American Experience. “Beauty Pageant Origins and Culture | American Experience | PBS.” Www.pbs.org, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/missamerica-beauty-pageant-origins-and-culture/.

Arnold, Dorothea. The Royal Women of Amarna : Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1996.

Bovet, Jeanne, and Michel Raymond. “Preferred Women’s Waist-To-Hip Ratio Variation over the Last 2,500 Years.” PLOS ONE, vol. 10, no. 4, 17 Apr. 2015, p. e0123284, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4401783/, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0123284.

Bruna, Denis. Fashioning the Body : An Intimate History of the Silhouette. New York, Bar Graduate Center, Decorative Arts, Design History, Material Culture By Yale University Press ; New Haven And London, 2015.

Ellis, Havelock. Man and Woman: A Study of Human Secondary Sexual Characters. United Kingdom: Scott, 1894. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Man_and_Woman/pAolrMxKmdYC?hl=en

Janega, Dr Eleanor. “On the Ideal Form of Women.” Going Medieval, 17 Nov. 2017, going-medieval.com/2017/11/17/on-the-ideal-form-of-women/.

Kyo, Cho, and Kyoko Selden. “Selections from ‘The Search for the Beautiful Woman: A Cultural History of Japanese and Chinese Beauty.’” Review of Japanese Culture and Society 27 (2015): 184–90. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43946370.

Paglia, Camille. “The Cruel Mirror: Body Type and Body Image as Reflected in Art.” Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America 23, no. 2 (2004): 4–7. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27949310.

Reischer, Erica, and Kathryn S. Koo. “The Body Beautiful: Symbolism and Agency in the Social World.” Annual Review of Anthropology 33 (2004): 297–317. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25064855.

Ruff, Christopher. “Variation in Human Body Size and Shape.” Annual Review of Anthropology 31 (2002): 211–32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4132878.

Singh, D., Singh, D. Shape and Significance of Feminine Beauty: An Evolutionary Perspective. Sex Roles 64, 723–731 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9938-z

[…] the busk was not as much to narrow the waist as to ensure good posture (Bruna, 61; Riordan, 175). Your late medieval ladies as portrayed in art are fairly often slumpers. But in the brave new world of the Renaissance, humanity was on the ascendant, asserting its power […]

LikeLike

The medieval pear-shaped point was the only one I was not familiar with. How fascinating!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] a rarer beauty found in lives fully lived. The same holds true when it comes to representing the ideal body shapePhotographers are challenging the convention of portraying only the ‘hourglass figure’ […]

LikeLike