There are precious few things that all modern women agree on, but most of us are glad that corsets have gone out of fashion. Corsets are infamous as torturous devices, specially designed to keep women in their place and helpless. But reality is a little more complicated than that, as it always is.

The Birth of the Corset

There are occasional claims that corsets go back to the ancient world, but there’s little evidence for it. Even if ancient women wore something similar (which is disputable), there’s no continuity between that and the 19th century corset.

The corsets that we now love to hate had their origin much later (Steele, 4,7). The word first appears in the 14ᵗʰ century, but it meant a dress (the whole dress) that included a fitted bodice (Bruno, 32). Even later on, there’s a lot of vocabulary confusion between the word “corset” and “corselette” and “stays” and “body” and “busk” and half a dozen other things. Not only are the words inconsistent, but so are the desired functions of the thing, whatever we’re calling it. If I use any vocabulary that doesn’t match your own knowledge, the chances are good that we’re both right, just for different time periods and different locations.

For example, there are a handful of metal (like iron) corsets that survive from the 16ᵗʰ century. They do, truly, look like instruments of torture. Fortunately for women of the past, historians do not believe those were corsets in the modern sense. They were prescribed by doctors, and their purpose was to correct spinal deformities. In other words, it’s an orthopedic brace, not a fashion statement. We still use stuff like that today for people who need it (Steele, 4; Bruna, 68).

The first true corsets appeared in the first half of the 16ᵗʰ century in Spain or Italy. It was separate from the dress, but it could be worn as either innerwear or outerwear. It incorporated some hard stiff material down the front (maybe whalebone, or possibly some other hard material) , especially in a fabric slot down the front of the corset. That hard piece was called a busk (Steele, 6,7,10).

At this stage, the purpose of the busk was not as much to narrow the waist as to ensure good posture (Bruna, 61; Riordan, 175). Your late medieval ladies as portrayed in art are fairly often slumpers. But in the brave new world of the Renaissance, humanity was on the ascendant, asserting its power and control over weak things, like previously uncrossable oceans and previously unknowable mysteries of the natural world. The weak things to be tamed certainly included human flesh.

It can’t have been particularly comfortable to have a straight, hard material stuffed down the front of your dress, but comfort wasn’t the point. Showing your mastery, control, and uprightness was. The body was a work of art, with emphasis on the “work” part.

There was not, as yet, any concept that nature was beautiful just the way it came. On the contrary, the idea was that both body and soul would grow to be misshapen if left to themselves. That is why children, both boys and girls, were put in corsets when very small. Like age two. Otherwise they’d grow up to be deformed (Steele, 12; Bruna, 89).

In retrospect, I think the world provides ample evidence that that is not true. But modern parenting advice is sometimes equally alarmist and nonsensical, so maybe not all that much has changed. Girls stayed in corsets for the rest of their lives. Boys were taken out of the corsets when they were breeched at about age 6 or 7. But don’t think men weren’t enhancing their bodies in other ways. This is the era of enormous codpieces (Bruna, 52, 131).

There’s a lot of uncertainty about how universal the corset was. As I said, it started in Spain and Italy and spread throughout Europe. England was a particularly enthusiastic adopter. Germany did it somewhat less (Steele, 26). Our best information is about the upper classes, as always. But what we know from many periods of history is that as soon as the rich and powerful start doing something, the middle and lower classes will copy it, to the extent that their circumstances and the laws allow. Certainly in later periods, the corset was worn by working women and even by some enslaved women (Steele, 27, 49; Bruna, 137).

The Evolving Corset

By the 17ᵗʰ century corsets were so universal that some tailors specialized. Their entire business was in corsets for women and children (Steele, 16; Bruna, 111).

There was and would continue to be enormous variation in the possible constructions because the purpose of them varied. You could get corsets for horseback riding, corsets for court appearances, corsets for maternity (Bruna, 111). Yes, I really mean it. Women wore corsets while pregnant.

Busks for posture stuck around, even as tight lacing for a smaller waist came in. But let’s be clear on what the corset actually did. It did not prevent women from putting on fat. It simply pushed the fat down to the hips, where women were supposed to be ample. Thin women who had no fat to push, might even pad the hips to get the right shape. Depending on the construction, the corset could also push fat up to the breasts. But the bust is its own topic of conversation, which I’ll be doing next week. The point right now is that women were not going for thin, not the way modern women often are. They just had strong views on where their fat was going to sit. Definitely on the hips, maybe on the breasts, not at all on the waist.

By the late 18ᵗʰ century, Enlightenment writers like Jean Jacques Rousseau had convinced many people that nature is beautiful, after all. Neoclassical looks (the flowing drapery types) were big and you only have to look at a few ancient Greek statues to realize those women weren’t fussed about whalebone to tighten their waistline. Therefore, neither were women of the French Revolution and Napoleonic era. The whalebone came out and the waistline moved up, right directly under the bust, which is why the dresses in Jane Austen movies look the way they do. I would hesitate to say that women had gone whole hog for the natural, let-it-all-hang-out look. Those chests look mighty busty to me, but thinning the waist by pushing fat to the hips was not deemed necessary because it was supposed to be a straightish line down from the empire waist. There was no need for it to suddenly tuck in at the natural waist. In 1802, Jane’s favorite author Fanny Burney wrote that everyone had doffed their corsets (Steele, 33). I’m sure that was an exaggeration, but I’ll believe that many had done so.

But that was over quickly. By 1814 the waistline on your dress was dropping back down to match the waistline on your actual body. And the no-corsets-freedom-of-yore was regarded as part and parcel of the disorder, lawlessness, and promiscuity of the Revolution, and I presume you know where that led. No, thank you. We prefer our women trussed and tied. Corsets were back with a vengeance.

And I do mean vengeance, for the 19ᵗʰ century brought several new developments, and not one of them was for the better. Not to modern sensibilities anyway.

The 19th Century Corset

Technical innovation meant that corsets were cheaper than they had ever been before. Also, front lacing was new. Now a woman could easily lace herself up. Previously, you needed a maid (or a lover) or a sister to help you. Not every woman had such a person (Steele, 43; Riordan, 178). Put those two things together and corsets were in reach for more women than ever.

Finally, metal eyelets, invented in 1828, meant that women could pull even tighter (Riordan, 177). Previously, there were limits because if you pulled too hard, you ripped the cording right through and out of the fabric. But if you can line those little holes with metal, then that’s no longer a problem. Suck in and pull away. Surviving 19th century corsets are, on average, smaller than 18th century versions (Steele, 44).

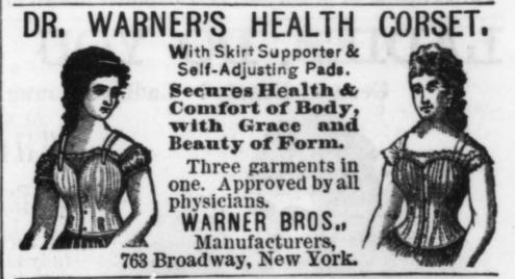

The rise of advertising also meant that manufacturers could try to convince women that even if they already had a corset (or three or five or twenty), they definitely needed another one. In the words of Marilyn Yalom, “To judge from the ads, a Frenchwoman had nothing better to do than spend her time changing between leisure corsets, sleeping corsets, pregnancy corsets, nursing corsets, and corsets for horseback riding, bathing, and bicycling” (Yalom, 168). Probably there was no woman in the world who actually used all those (especially the sleeping corsets), but it wasn’t for lack of trying by the marketing departments.

These innovations meant more and more flesh was getting squeezed tighter and tighter, but there was simultaneously a new and contradictory idea. The idea was that your corset should be comfortable while you are getting squeezed. No one in previous centuries had seriously suggested such a ludicrous thing (Steele, 44).

The search for a corset that simultaneously gave you a perfect figure AND felt perfectly free and easy was a gold mine for corset makers. They could claim that only low-quality, badly fitted corsets hurt. Just fork over the premium price for this new design and all will be well (Steele, 42). Reality hit only when the transaction was over.

In the mid-19th century, when skirts were enormous, the contrast between the waist and the hips made anyone’s waist look small by comparison, which doesn’t mean they weren’t pulling it tight. But there was some hope for ladies who were larger. Later in the century, the styles changed, skirts became hip-hugging and corsets were lengthened to cover those hips as well, Hips are a far less malleable portion of your anatomy. One magazine complained that the new fashions favored thin people, “to the despair of everyone else” (Bruna, 155). Suggesting that that had not always been the case.

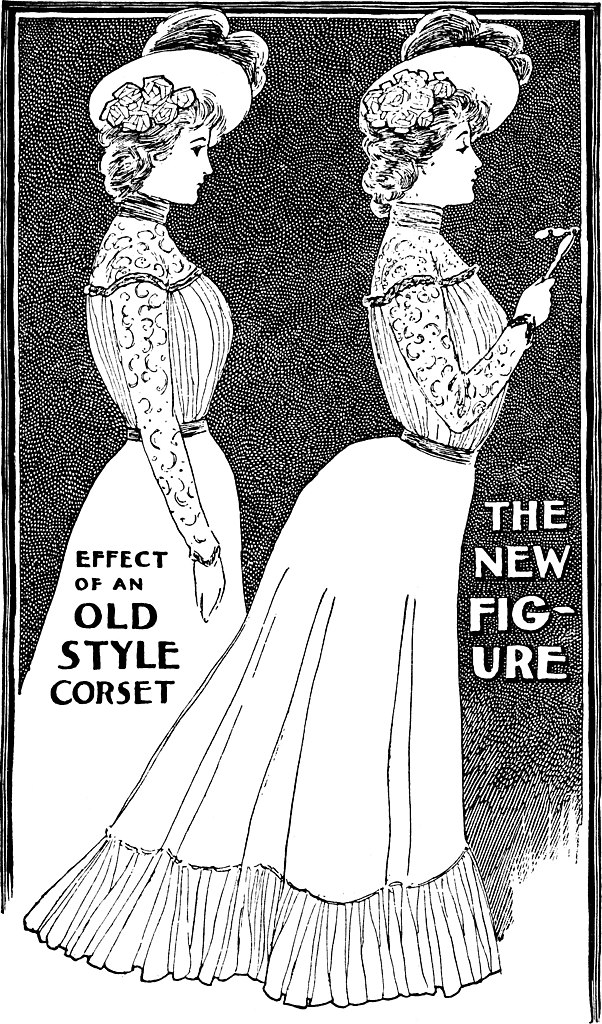

Worse than that, it was designed to make an S-shape out of your body. This is different from the medieval S-shape I mentioned last week. That one slumped your top and thrust your belly and hips forward. This one is just the opposite. These corsets had a hard paddle shape in the back, so that they thrust your chest forward and your hips backward (Bruna, 164). It was a technological marvel. It also caused lower back pain, hyperextension, bladder and uterine problems (Steele, 85). It was far more uncomfortable than what previous generations had endured. So much for progress.

How Small Can You Go?

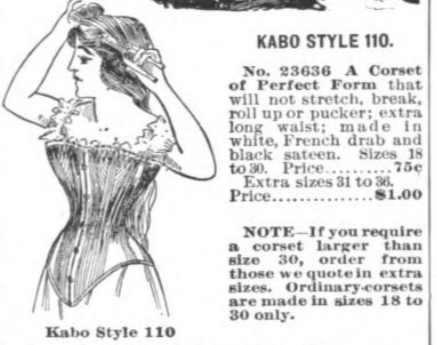

I have now given you the basic evolution of the corset to its highpoint (or low point, depending on how you want to consider it), but there are still a few questions to answer. And the first is how small can you go? In Gone with the Wind, Scarlett O’ Hara’s waist was famously 17 inches, but that’s fiction. Judging from the advertisements in English and American periodicals, that was ridiculously small. Nineteenth century corset makers regularly advertised a range of 18 to 30-inch corsets, with larger sizes not all that hard to find. Bear in mind that those measurements are the minimum the corsets could go. You don’t have to lace it fully closed. You can wear it larger than those amounts. Many women were wearing them bigger (Steele, 102), and Scarlett O’Hara would have had to special order hers.

For comparison with modern times, the CDC reports that the average waist size for women over 20 in the United States is 38.7 inches (CDC, FastStats – Body Measurements). So yes, a 19th century corset would be a pretty serious tummy tuck except for a few things:

- The CDC also reports that 73.6% of Americans over 20 are overweight (CDC, FastStats – Overweight Prevalence). That was probably not the case in the 19th century. Doctors of that time period estimated that an average woman’s waist was 27 to 29 inches (Steele, 103). Whether that number was accurately sampled, whether it was already artificially reduced because of corset wearing in the formative years, I have no idea, but you’ll notice that it is within the range of the advertised corset sizes.

- Also, corset makers were selling to girls younger than 20. We would naturally expect some corsets to be very small because they were for younger, smaller girls.

- And finally, remember that even today clothing manufacturers do a thing called vanity sizing: they label their clothes as smaller than they really are. Surviving corsets tell much the same story. In very few is it possible to draw them smaller than 20 inches, and most are larger than that (Steele, 100).

Put it all together and it suggests that many women were maybe not extremists. They were tucking their tummies, and I’m sure it was uncomfortable by modern standards. But they weren’t living with torture to quite the extent that Scarlett O’Hara has led us to believe.

Furthermore, the average woman would lace differently at different times of day: loosest in the morning at home, a bit more for making her afternoon calls, tightest of all for the evening entertainment, not at all in bed at night (Steele, 109; Bruna, 193). This schedule, of course, is for women who could afford to make calls and have any evening entertainment.

It is true that there are 19th century accounts that give much smaller numbers than the 18-30 range I just mentioned, but there is no reason to accept them all as true. There was much incentive for exaggerating, and some of the most famous accounts are clearly eroticized. They read just like a pornographic novel, and like pornography, they have little in common with reality (Steele, 88).

On the contrary, tight lacing (as opposed to just moderate lacing) was decried by men and women alike. Respectable women didn’t ever admit to tight lacing. That would have been frivolous and vain. Also, it would suggest that they needed to tight lace, and of course they preferred to be thought naturally small-waisted (Steele, 87). Now of course this doesn’t mean that none of them were tight lacing, but the concept of really tight lacing was not admired.

Who Were the Enforcers?

Then there is the question of who was enforcing the corset? As early as 1899, a male economist said that corsets were the tools by which rich men made women unable to work so they would be status objects, not people (Riordan, 190). It’s a claim guaranteed to stoke the smoldering fire inside a feminist’s heart, but it’s not quite correct. Women did work in corsets. There were corsets sold specifically for housemaids. They were extra strong and extra cheap (Steele, 46).

For another thing, it assumes that no woman ever put one of these things on of her own free will. But the first-hand accounts suggest that the people demanding that girls don the dreaded device were not men, rich or otherwise. It was usually an older female: your mother, your governess, or your boarding school mistress (Steele, 51). These are the ones for which we have written accounts. The lower classes, of course, just left us fewer records.

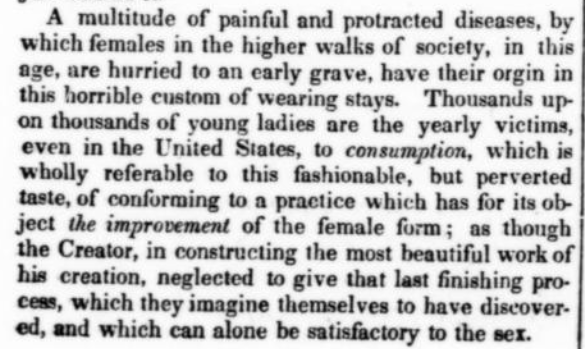

There’s actually a long line of published men who said the corset was a stupid idea and women should stop it. Or at least stop lacing it so tight. As early as 1440, one writer accused outrageously dressed women of “transfiguring the well-shaped work of God” (Bruna, 34). In 1581, one surgeon was warning of death-by-too-tight-lacing (Steele, 13). Later writers decried the vanity and the affectation and warned of a whole host of negative side effects. Everything from withering rottenness (Steele, 14) to asthma and tuberculosis (Steele, 15) to ugly children (Riordan, 190), to breast cancer (Steele, 80), to impure feelings (Steele, 77). All of them caused by the corset.

The warnings came from every quarter: doctors, philosophers, economists, and more, but it had little effect for most of the period. There was simply too much pressure on girls and women to wear the corset anyway, no matter the cost.

Some of that pressure was men’s fault. The corset became an erotic object, with love verses inscribed on the whalebone (Riordan, 175). Paintings of women in corsets were as titillating to Victorian men as any nude (Steele, 11, 133). In a world where a woman not only had her own sex drive to satisfy but was also frequently dependent on her pleasing appearance to attract a man to supply her basic needs, looking beautiful was neither vain nor trivial. It was literally survival, even for women who would have been horrified to think of themselves as prostitutes. It’s no wonder mothers and governesses forced girls to wear them. We force modern children, both girls and boys, to do schoolwork even when they don’t want to. It’s an investment for their future.

But that isn’t the whole story either. Women generally want to be beautiful. It’s not just about getting a man. It’s also a matter of self-confidence and prestige even in front of other women. Given a beauty standard that fixated on a small waistline, it makes perfect sense that women would choose the corset. Themselves. It’s the standard that was ridiculous. Not the desire of women to achieve a preexisting standard.

The bottom line is that women were not passive victims here. They were active participants.

Just How Bad for You Was It?

The vast majority of the health scares were patently untrue. Corsets do not cause breast cancer or tuberculosis or impure feelings. We’re capable of all of those things without any need to wear a corset.

But depending on how tightly they are laced, corsets do force shallow breathing, which can make fainting more likely. They probably did cause some digestive problems like constipation. In extreme cases, they can reshape the ribs, especially when worn during the formative years.

In the short run, corsets do provide back support, just as many supporters claimed. In the long run, the constant support allows the back muscles to atrophy. Soon, you really do need the corset. You can see why people claimed the female body was too weak support itself. They were just mixing up cause and effect (Steele, 68-75). In many times and places, the corset was also serving for the purposes that we now use a modern bra. And it’s true that many women do need that support, but that bears into the claims that the female body really needed the corset. That’s because some women did.

That much has been verified with studies from the few modern women who have worn corsets for a while. Some of the rest of the health scares, we can’t really verify. The idea that they cause miscarriages, for example, can’t be verified. The historical records don’t exist. There’s no ethical way we could find out with a modern study.

The Corset’s Demise

So what happened to the corset? Well, as per usual it’s a complicated set of variables.

Dress reformers complained enough to make some headway. Women’s rights activists declared that women were free, their waists included. The fashions changed. The S-shaped figure was seen for the ridiculous goose-like posture that it is.

All of these things played a role, but they probably wouldn’t have been enough without the rise of sports. Opening up bicycling, tennis, swimming, and the like to women meant that the corset was more restrictive than it had ever been before when women weren’t trying to do those things. Movement was now glamorous (Riordan, 185-187).

Also sports meant that waists could be toned, without any whalebone. The new beauty standard was still to have a small waist. Only you were supposed to accomplish it with exercise, and later we added diet and plastic surgery. One of my sources calls this the psychological corset (Bruna, 238). And I probably don’t need to tell you that the things women have done to themselves pursuing that goal have sometimes been every bit as damaging as the physical corset ever was.

Even after women doffed their corsets in the early 20th century, they still wore foundational garments in dizzying variety until the 1960s and 1970s. More recently corsets and other foundational garments have staged a comeback. High profile women from Madonna to Lady Gaga have worn corsets as outerwear. But for those of us women who don’t aspire to such lofty heights, it’s inner foundational wear that’s coming back. I know partly because my sources tell me so, but also because the Internet advertises shapewear to me practically every single day, along with a host of comments from people saying they don’t work and they hurt, as well as people saying yes they do work and they feel great. I’m pleased to say that I don’t think any whales have been killed to produce the shapewear, and I don’t think anyone’s being forced to wear them. So some things really do get better. Maybe not perfect, but better.

Selected Sources

CDC. “FastStats – Body Measurements.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 10 Sept. 2021, http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/body-measurements.htm.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “FastStats – Overweight Prevalence.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 5 Jan. 2023, http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/obesity-overweight.htm.

Paré, Ambroise., Hamby, Wallace Bernard. Case Reports and Autopsy Records. United States: Thomas, 1960.

Riordan, Teresa. Inventing Beauty : A History of the Innovations That Have Made Us Beautiful. New York Broadway Books, 2004.

Steele, Valerie. The Corset: A Cultural History. New Haven, Yale University Press, 2001.

Yalom, Marilyn. A History of the Breast. New York, Ballantine Books, 1998.

[…] the meantime the corset had appeared on the scene. The modern image of a corset is that it is about squeezing the waist, but the corset could do more […]

LikeLike

[…] down precipitously. There were Victorian women who thought nothing of squeezing their waist in a corset or strapping on a rubber bust, but they would not have dreamed of putting on lipstick or rouge […]

LikeLike

[…] seem to be particularly new. Throughout history and around the globe, women have routinely squeezed, bound, crushed, tweezed, poisoned, pricked, and stretched various portions of their anatomy, […]

LikeLike