Yes, we are talking about breasts today, and it occurred to me to wonder whether that means I’m supposed to mark this episode as explicit. But I didn’t. Because it’s not. All I’m interested in is how women in history boosted their breasts up or bound them down. If our culture’s over-eroticization of breasts is going to make that troubling for you, give it a miss. Come back next week for footbinding, which was also erotic at the time, but I’m guessing doesn’t strike you that way at all. Really, it’s all a matter of your cultural expectations. Okay, here we go:

The Composition of the Breast

The first mystery about breasts is why a woman has them at all. Yes, I know that we’re mammals, and by definition we nurse our young with milk through mammary glands. I’m with you so far, but out of multiple thousands of mammalian species, guess how many have mammary glands large enough to be visible even when the female is neither pregnant not nursing? Yes, that’s right. Just one. Just us (Emera, 31).

The composition of our ever-present breasts is largely fat. Another shocker. I mean fat is supposed to be the enemy, right? That’s definitely the message I’ve gotten from my modern culture. Only turns out it’s not the enemy, as long as it collects in two locations, one on each side of your chest. At least that’s the case if you happen to live in a time when big breasts are the fashion. For much of history the fashion was to have small ones.

Breasts in the Ancient World

I’m going to pass lightly by thousands of years and even more cultures for lack of evidence. The mostly male writers of historical records were reasonably interested in breasts, but quite uninterested in the day-to-day management of them. The Old Testament, for example, goes on and on and on about breasts in Song of Solomon, but Genesis doesn’t so much as mention whether Eve needed a fig leaf for her upper half, or just one for the lower bit?

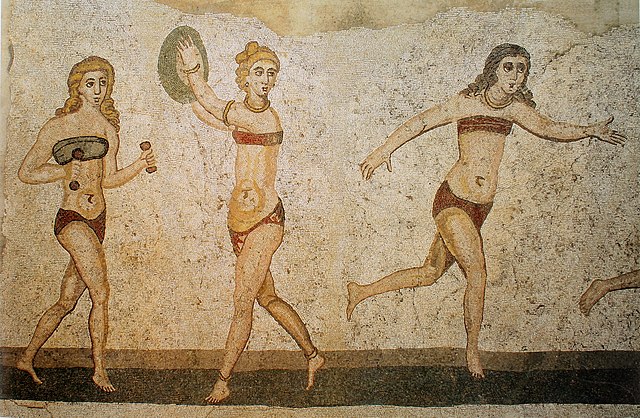

There are hints that Greek and Roman women bound their breasts with tightly wrapped fabric, which is variously called a strophium, a fascia, or a mamillare. It’s mentioned by Homer in the Iliad (Book XIV) and by Aristophanes in Lysistrata and by others in other works, but as far as I can tell it’s always mentioned just in passing. As in passing it off. A prelude to other things, as it were.

There are a few pieces of classical art that show such a thing.

But there’s plenty of other art where the woman is clearly wearing no such thing. Even some of the clothed statues make it clear there is nothing under that very thin dress. So we’re left not knowing what was normal and for what status of woman doing which activities. Probably it wasn’t uniform. I’m sure different women did different things, mostly without leaving any record whatsoever.

Not much changes in our evidence for a long, long time.

Medieval Breasts

Only when we get to the late Middle Ages do things get a little clearer. Bodices by then were very fitted, which certainly suggests that some sort of breast control was happening, but big was not the point. In the late 1200s, Jean de Meung composed the second half of the Romance of the Rose, which gives plenty of beauty tips for young women. For example, it says: “If she’s not lovely, she should dress / Even the ugliest, to impress.” It goes on with what to do if you lose your hair (wear a wig) or if your skin isn’t flawless (cosmetics and gloves). And more to the point today are these lines:

“And if her breasts seem too heavy

She should have a towel ready,

To press them flat to her chest,

And round her sides secure the rest,

stitched or knotted, whichever way,

So she can go abroad and play.”

(Meung, chapter 73)

There is nothing whatsoever about what to do if your breasts are too small. That evidently wasn’t a concern. Big breasts were associated with nursing, which was not sexy, especially as some people believed you shouldn’t even have sex if you are nursing (Yalom, 75). Big breasts were also associated with old age, when they began to sag.

A century later the concern was whether the breasts were visible. In 1371, the French knight Geoffroy de La Tour Landry was writing to his daughters to keep their breasts covered, for goodness sake. He also mentions their throats. Those have to be covered too (La Tour Landry, line 155). Like many a father de la Tour Landry may have been fighting a losing battle there.

A generation later Agnes Sorel came to the French court and bewitched the king with her low-cut gowns that became all the rage. We’re not just talking cleavage here. Women were showing whole thing, at least according to the hand wringers (Yalom, 51). If so, then they certainly weren’t binding them up anymore.

Renaissance and Baroque Bras

By the following century, there was medical advice on offer. But still the emphasis is on small. Jean Liebault wrote in 1582 that a beautiful chest would be “two round apples, small, firm and solid, not too attached, but which come and go like waves” (Liebault, 316). In pursuit of this end, he recommended that a woman with small, firm apples, should keep them that way by crushing cumin seeds with water to make a paste, smearing it over her breasts, and binding them tightly in a rag dipped in vinegar. After three days, she was to take it all off and crush a lily bulb in water, smear that on, bind it with another vinegar soaked wrap, and leave it for another three days (Liebault, 316). For the record, I have not tried this at home.

In the meantime the corset had appeared on the scene. The modern image of a corset is that it is about squeezing the waist, but the corset could do more than that. It played a role in the breasts as well.

Early corsets contained a fabric slot for a busk, which was a rigid piece of whalebone, wood, or metal, and it was meant to ensure very straight posture. In some decades, the busk was very long, it came right up and over the breasts. In other words, the busk crushed the breasts down so that there is hardly even a hint of a bulge in the lady’s torso. See paintings of Elizabeth I of England for that.

But in other decades the busk did not come so high. If you made it just a wee bit lower, then the effect it has is to boost and lift the breasts, making them far more bulgy than they would have been on their own. It was basically the effect of a push-up bra before the push-up bra had been invented. See several Artemisia Gentileschi paintings for that.

Most modern bras support the breasts with straps that put the weight on the shoulders. The corset instead supported from beneath, putting the weight on the waist and hips. Depending on the lacing, it could also push some of that fat that you did not want on your waist up into the breasts where the more fat the better (Riordan, 66).

You may notice we are no longer going for small breasts. On the whole, since the Renaissance, the general trend has been to favor larger breasts (Yalom, 90). There is some occasional backsliding, which I will get to. But no matter which time period we are talking about, I would not like you to get the idea that all women everywhere were handling this in exactly the same way.

In one of the most astounding archaeological finds ever, Lengberg Castle in Austria has turned up some actual “bras.” The word bra here is in quotes, because there’s no linear connection between the bras sold today and these remnants, but it sure looks like a bra: two cups and shoulder straps. It was all buried in a 15ᵗʰ century renovation of the castle. Sometimes the cups were sewn into a dress or underdress, but other times not (Nutz).

Breasts in the Age of Enlightenment

If art history is any guide, then it was the Dutch who went for really large breasts after all. Or at least so says one of my sources (Yalom, 102). When I took a look I certainly saw the ample bosoms, but I noticed also that they were biggest in brothel scenes. In other words, large breasts may have been popular (no doubt they were), but I’m not so sure that they weren’t necessarily classy.

But the 18ᵗʰ century would change that. Corsets of this era did not just push the breasts up. They also forced the shoulder blades back. It sounds terribly uncomfortable, and some of the contemporary sources agree with that description. But the effect was to project the chest forwards. (Yalom, 105; Steele, 20). Let’s just say it was a prominent display, and it was done by the upper class and the classy.

The French Revolution was all about liberation, but as far as the female body was concerned, that all depends on what you mean by “liberate.” Women did discard the corset, and it’s not at all clear to me what they did about their breasts with neither support from above or below, but that was a brief aberration, and corsets were in full force for the 19ᵗʰ century, all of them boosting that bust.

Indeed, the bust was a lot of the rationale for claiming corsets were necessary, and women really needed the corset. In German, one word for the corset was Stützbrust, which literally means bust supporter (Yalom, 168).

Faking the Bust

By now big breasts were definitely in, which meant that women who were not so well endowed had a problem. And a problem like that is a marketer’s dream.

The earliest U.S. patent for a false bosom was granted to Anne S Mclean in 1858. Her invention is a 4-inch wire cone you inserted into your corset (Riordan, 72).

Presumably many a woman had already figured out how to stuff their own corset even if they hadn’t gotten a patent on it. But few of them would have had the resources to make their false bosom out of rubber. Not without industrial help anyway. Fortunately, industry was there to help, and rubber manufacturers sold false bosoms considerably earlier than they sold rubber tires (Riordan, 75).

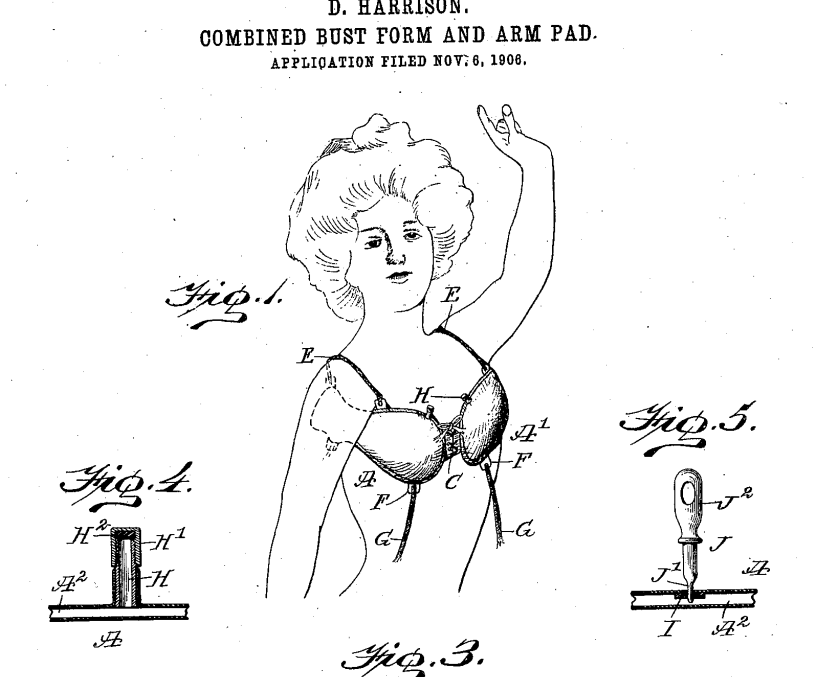

The bad news for small-breasted women was that rubber had a tendency to deflate at embarrassing moments. By the end of the 19ᵗʰ century a certain Dora Harrison had invented a fix for that too. Her design for a 1907 patent came with nozzles placed close to the mouth so you could quicky reinflate if necessary (Harrison). I took a look at the drawings in her patent, and I am not absolutely sure I could contort my neck enough to inflate those things, but that was no concern of the US patent office.

For those who wanted the real deal, marketers were happy to sell you any number of methods to make your breasts get fleshier. Cumin seeds were no longer the way. Maybe because those were supposed to keep your breasts small. But obviously all we needed here was the opposite treatment and a large variety of bottled creams and potions were on offer. However, the best of the best (at least as far as modern amusement goes) was the two-part regime called the Princess Bust Developer and Bust Cream or Food. This very awkward sounding product appeared in the 1897 Sears Roebuck catalog and for a mere $1.46, you could get “a new scientific help to nature.” “If nature has not favored you with that greatest charm, a bosom, full and perfect,” then the Princess Bust Developer was the answer. It was a metal tool that looks very much like a toilet plunger, and it promised to “enlarge any lady’s bust from 2 to 3 inches!” Especially when combined with a massage with the bust cream, modestly described as the “greatest toilet requisite ever!” The bottom of the ad warns against buying medicines and treatments offered by irresponsible companies (Sears, 31).

I am going to freely admit here that I do not own a princess bust developer and I have not tried this at home either. But I’m skeptical.

By the 1920s, everything changed. Corsets were out, more or less, and most women no longer wanted their busts developed. On the contrary, the boyish look was in, sexual interest was on the newly revealed legs and on the newly decorated face. Technically, the bra had been invented, but it was flattening, not enhancing, and it was sometimes sewn directly into a slip or camisole. Also it was called a brassiere. Not until the 30s was it common enough to be shortened to just bra (Riordan, 92).

But fashion never stands still, so by the 30s, you could also purchase “falsies” to stick into the bra. We’re back to big is beautiful.

Bigger Is Beautiful

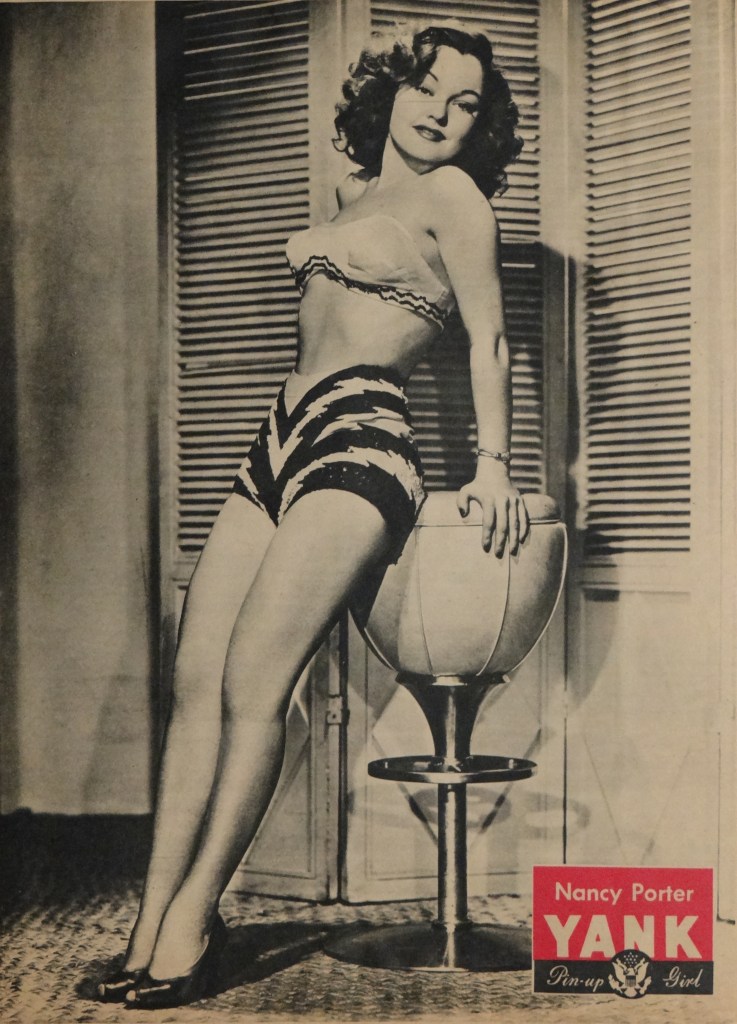

In 1940s, it was even bigger is beautiful. The pinup girls of World War II were definitely bigger. A little bit of leg, a little bit of makeup, those were all in the ordinary now, so other means were needed to get the same effect.

Photographer Ralph Stein went to Hollywood in 1945 to make a series of pin-up pictures for the GIs. He reported that “the makeup woman wasn’t quite satisfied with the fullness of the starlet’s sweater. She inserted a pair of felt pads about two inches in diameter, backed off, looked hard, and inserted two more. ‘Enough?’ she asked us … We hemmed and hawed a bit. The makeup lady decided for us. ‘What the hell,’ she said, ‘this is for the soldier boys’ and put three more pads over each breast.” (Yalom, 137)

These pictures were distributed among the troops by way of magazine, and opinion was a little divided on them, even amongst those soldier boys themselves.

Staff Sergeant AE Lewis wrote a letter to the editor saying he was tired of such pictures. “On recent furlough,” he added, “I noticed some very choice females who were wearing coveralls. They were going to and from work. They had been working hard turning out the stuff we need to win the war. Anyway they are doing something besides advertising their anatomy. Why couldn’t the war plants choose the sweet things among them and turn their pictures in if these doggies must drool over something? After all, they are the gals we are coming home to and the ones who are doing the most to get us home. Some of these fanny dancers wouldn’t give up their ‘careers’ if the enemy was on the roof.”

But not everyone agreed. Just under his letter they printed one one from Private Farrel E. Fuller, who said “We’re hoping for more.” (Yank, Mail Call).

It’s not really surprising that breasts were boosted in the war. They are the most obvious sign of femininity. In a world that was extraordinarily gender segregated, a little (or a lot) of femininity was exactly what was wanted.

Post-War Breasts

As Sergeant Lewis predicted, the GIs went home to reality, and the reality is most women aren’t built like that. But it wasn’t for lack of trying. By the time the war was over, millions of women were trying to get, not an hourglass figure, but a top-heavy figure. They wanted what were called Hollywood proportions, which meant a bust measurement one inch wider than their hips (Yalom, 177; Riordan, 104).

Bras were now the norm and stuffing them was still a possibility. The 1951 Sears Roebuck catalog offered 22 types of falsies (Haiken, 243). But stuffing has drawbacks. Many women didn’t want the bother or the risk. Plus they wanted to look good even when the bra came off.

And by now women had options. As far as I know, Sears Roebuck was no longer selling the Princess Bust Developer, but the basic concept was not dead. The Mark Eden bust developer promised inches of growth within weeks for only $9.95, if you just did the special exercises it described. Various books and devices promised the same effects using hydromassage or even your very own subconscious mind powers (Riordan, 107).

But the most effective option is the one that is still with us: cosmetic surgery.

Breast reduction was pioneered in the 1920s. Since over large breasts is a genuine medical condition with genuine discomfort involved, the medical community generally accepted it as a genuine health issue for which surgery was warranted. The fact that the 1920s also favored small breasts for aesthetic reasons was perhaps not coincidental, but we’ll try to ignore that (Haiken, 232).

Breast augmentation was an altogether different thing. A few options had been tried and discarded as not working, even as early as the 1890s. It was not until the 1940s, the age of the Hollywood bust that women en masse began pestering their mostly unsympathetic doctors. It was all vanity, the critics said. Not a genuine health issue at all, and therefore unworthy of a surgeon’s time.

Women cried foul (their concerns were being brushed aside, as usual), and what about the psychological impact? Stories circulated about women who killed themselves because they were so upset about being flat-chested. I could wax eloquent on that for a while, but I won’t because it would take too long, and there may be an episode later in this series about historical body image as an emotional issue. I’ll save it for then.

Anyway, alarmist stories aside, caution really was warranted with regard to breast augmentation. The procedures were still experimental. Someone has to go first. Despite this, many women were eager to have the less squeamish doctors insert various substances into their breasts. These women felt, according to one survey of recent patients, that stuffing their bras was cheating, but surgery was not. “One might be in an accident,” one satisfied customer explained, “and be found out and feel so ashamed that one couldn’t face people again” (Haiken, 244).

Happy customers were sometimes less happy over time. The injected material would become hard while breast tissue infiltrated it, which meant it couldn’t be removed. There were amputations and infections. Not in everyone, you understand, but in some (Haiken, 245).

The first silicone injections cannot be traced because they were underground, unrecorded operations. It was associated with strippers. It wasn’t something nice women did. No one pretended it was anything other than cosmetic. Long-term effects were entirely unknown.

Meanwhile newspapers reported that injected silicone tended to migrate to other locations, sometimes forming lumps that were mistaken for breast cancer (Haiken, 249). Sometimes the injections became infected and had to be amputated. Regulations simply drove the business underground and over the border (Haiken, 251). But time was on the side of the breast augmenters, especially with a growing number of breast cancer survivors who could say, yes, it was too a medical issue. The methods got safer, and as the data came in, and the social acceptance got greater.

In some ways that was ironic because it was happening right as we got back to smaller is beautiful in the late 60s and 70s. The androgynous look was back, and feminists were burning their bras to draw a line under their new freedom to do whatever they wanted. (Actually the first bra-burning wasn’t a burning, they just threw the bras away.) What usually went unsaid was that going braless is much more possible if you happen to be small breasted.

However, it was brief. The 80s saw a full-fledged return to femininity and the Wall Street Journal declared that “Breasts are back in style” (Yalom, 181). Wall Street cared because big bosoms were big business. Women could now buy the bust of their dreams whether with a push-up bra or an increasingly safe medical procedure. Feminists were left arguing whether the new trend meant newly empowered women were now free to really be women (in which case yay!) or whether it meant the newly threatened men were stressing their preferences for traditional non-empowered women (in which case, boo!) (Yalom, 181). If you ask me, it didn’t mean either of those things. Like every other fashion trend, big breasts come and big breasts go. Explanations are mostly rationalizing after the fact. In the 90s, Marilyn Yalom, author of The History of the Breast was able to write that “American women spend untold millions for products and services to reduce the lower half of their bodies and increase the upper half” (Yalom, 7). Breast augmentation remains very popular today in the 2020s. Much more popular that breast reduction, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons. But the evidence of history suggests that at some point, we’ll be going back the other direction again.

Selected Sources

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. The American Society of Plastic Surgeons ® Procedural Statistics Data Insights Partners: 2022 ASPS Procedural Statistics Release. 26 Sept. 2023.

Aristophanes. “Lysistrata (411 BC).” Www.gutenberg.org, 23 Aug. 2015, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/49764/49764-h/49764-h.htm. Accessed 13 July 2024.

Emera, Dr. Deena. A Brief History of the Female Body. Sourcebooks, Inc., 15 Aug. 2023.

Haiken, Elizabeth. Venus Envy : A History of Cosmetic Surgery. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017.

Harrison, Dora. Combined Bust Form and Arm Pad. 23 July 1907, ppubs.uspto.gov/dirsearch-public/print/downloadPdf/0861115. Accessed 13 July 2024.

Homer . “The Iliad (8th Century BCE).” Www.gutenberg.org, 18 Sept. 1999, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/2199/2199-h/2199-h.htm.

La Tour Landry, Geoffroy de. “Le Livre Du Chevalier de La Tour Landry Pour l’Enseignement de Ses Filles (1371-72).” Https://Www.gutenberg.org/Files/68885/68885-h/68885-H.htm, 31 Aug. 2022, http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/68885/pg68885-images.html. Accessed 13 July 2024.

Liebault, Jean. Trois Livres de l’Embellissement et Ornement Du Corps Humain. Pris Du Latin. Internet Archive, 1582, archive.org/details/BIUSante_88095/page/n331/mode/2up. Accessed 13 July 2024.

“Mail Call.” Yank: The Army Weekly, vol. 3, no. 35, 16 Feb. 1945, p. 14, archive.org/details/1945-02-16YankMagazine/page/n13/mode/2up?view=theater. Accessed 15 July 2024.

Meung, Jean de. “Meung, Jean de (C. 1240–C. 1305) – the Romance of the Rose, the Continuation. Download Options.” Www.poetryintranslation.com, Trans. by A.S. Kline, http://www.poetryintranslation.com/klineasleromandelarosecontinuation.php. Accessed 13 July 2024.

Nutz, Beatrix, Marion McNealy, and Rachel Case. “The Lengberg Finds. Remnants of a Lost 15th Century Tailoring Revolution. NESAT XIII.” Archaeological Textiles – Links Between Past and Present. NESAT XIII, 2017.

Sears, Roebuck Catalogue, 1897 Edition. Sears Roebuck, 1897, archive.org/details/1897searsroebuck0000unse/page/30/mode/2up?view=theater. Accessed 13 July 2024.

That Princess Bust Developer is a hoot! I don’t think “absolutely harmless” nor “perfectly safe” apply to a plunger meant for anywhere on the human body– and yet, I see ads today about a plunger for mosquito bites.

Oh, the things people sell.

LikeLike

[…] were Victorian women who thought nothing of squeezing their waist in a corset or strapping on a rubber bust, but they would not have dreamed of putting on lipstick or rouge (Riordan, 1). How […]

LikeLike

[…] to be particularly new. Throughout history and around the globe, women have routinely squeezed, bound, crushed, tweezed, poisoned, pricked, and stretched various portions of their anatomy, sometimes […]

LikeLike