China has been a very literate society for a very long time, and we have thousands of documents that discuss bound feet. It’s just a shame that almost all of them were written by men. That means the record is heavy on hormone-inspired odes to beauty. It’s relatively light on the actual lived experiences of hundreds of millions of women. After sifting out the pornographic trash, here is the story, or at least my closest stab at it:

The origins of footbinding are lost in time, but I think it is safe to say that the first woman to do it could not possibly have imagined what was coming. Our oldest textual reference to bound feet was written in the 1100s by Zhang Bangji. Already he didn’t know where the custom came from, but he says that ancient collections of poetry don’t mention it, so it must be recent (Ko, 111).

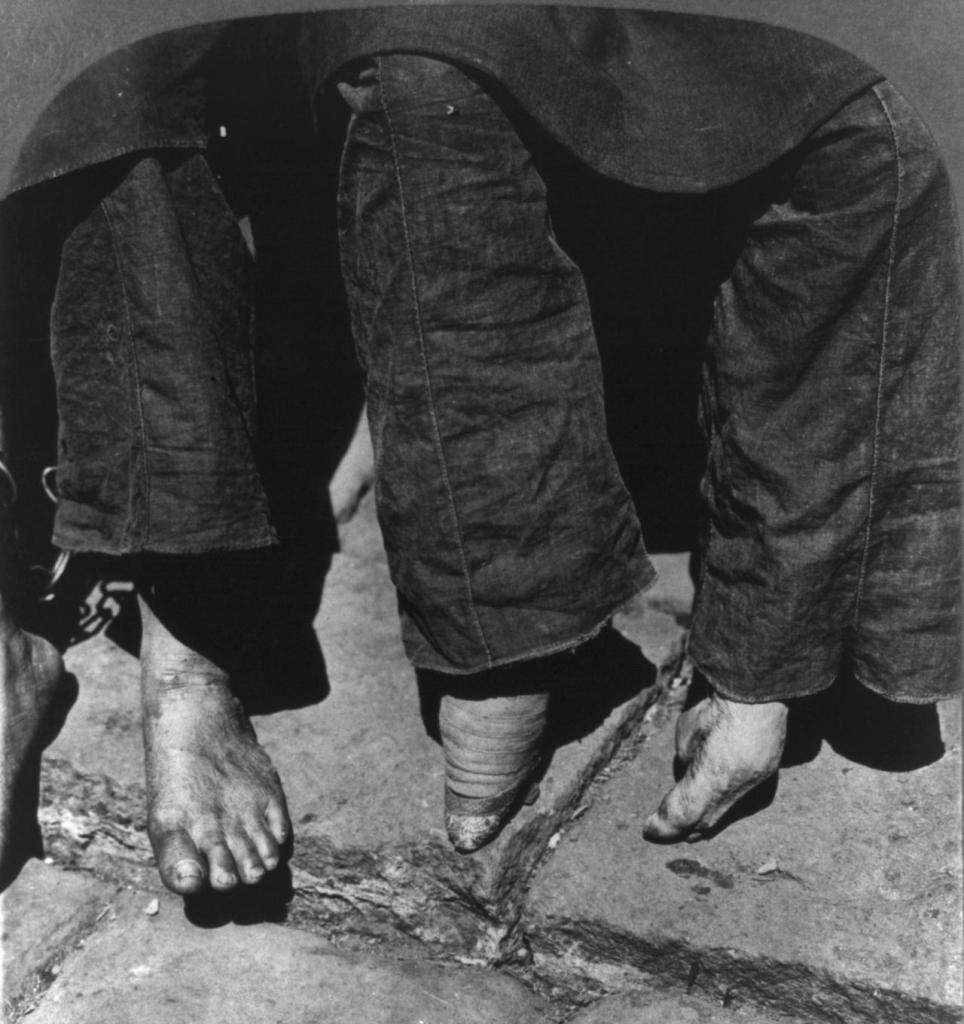

Archaeology agrees with him. Our oldest skeletal evidence is from the 1200s. The excavated women would be ugly by the standards of the later Chinese because their feet weren’t particularly small. They were just narrow, and the toes were upturned (Ko, 191). I am talking about their actual feet here, not just their shoes, of which the tombs contained many.

By this point the written records are picking up. They include many contradictory origin stories, all of which sound like legends. Most of them involve some powerful man obsessing over the beauty of his favorite concubine’s small feet (Ko, 114). Which is exactly what Chinese men proceeded to do. For the next 700 years.

Feet seem like an odd thing to fixate on to me. They’re not part of the reproductive system. They’re nowhere near the reproductive system. Nevertheless, they are the focus of Chinese eroticism. Where Western love poetry would drone on about the breasts, Chinese poetry often drones on about the feet.

Creating and Living with Bound Feet

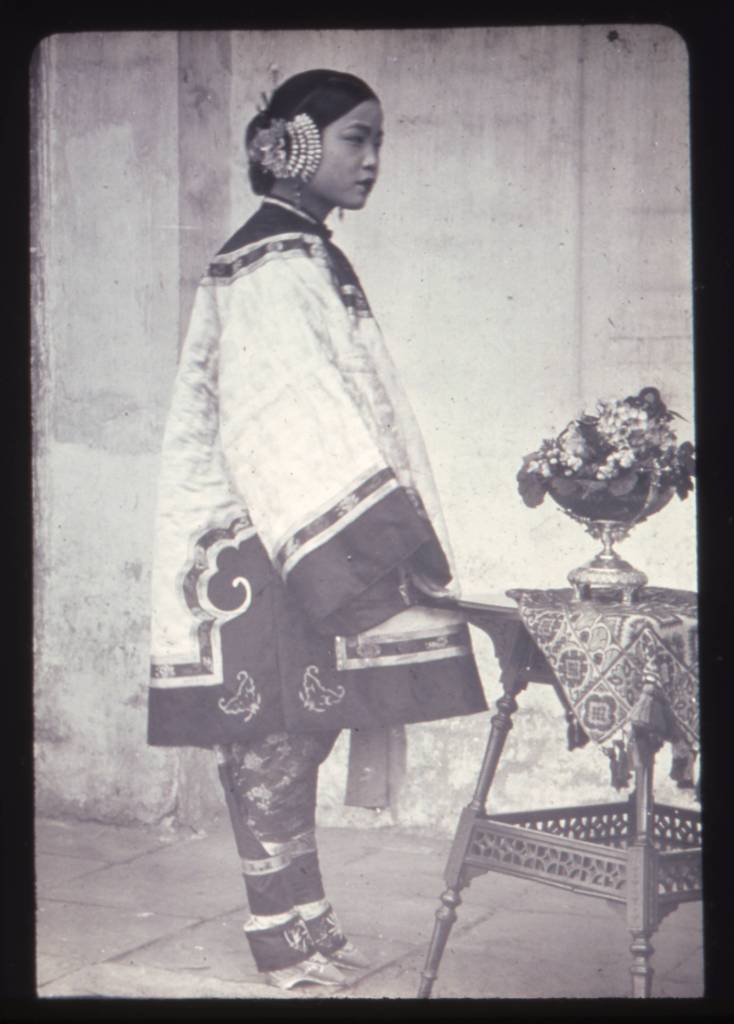

In the early days, footbinding was an upper-class thing. Even in Western cultures, ludicrous footwear has been a sign of social class, a symbol that you don’t have to be on your feet, working hard all day. Deliberately reshaping your foot was a more extreme version of the same idea. However, where the upper classes go, everyone else soon follows, including women who actually do have to be on their feet all day. Increasingly if you hoped for a good marriage, you needed bound feet. If you hoped even to be a maid or an entertainer in a big house, you needed bound feet.

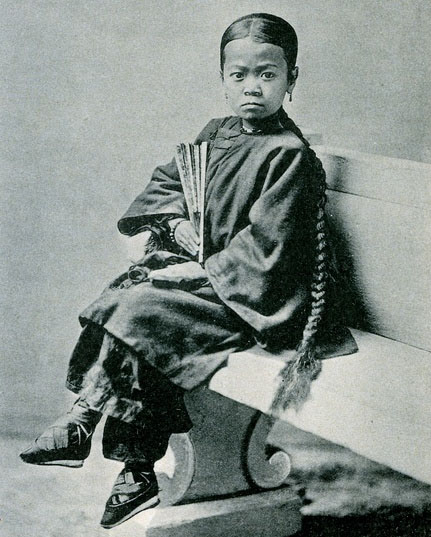

The only way to get them was to start the process young. So a mother who wanted her daughter to have a good future would ensure it by inflicting pain, probably starting when the girl was about four or five. Certainly by age seven, when the bones were still small and flexible. As I’ve alluded, the exact shape and the methods varied over time and probably location, but here is the process based on sources from the 19ᵗʰ and 20ᵗʰ century:

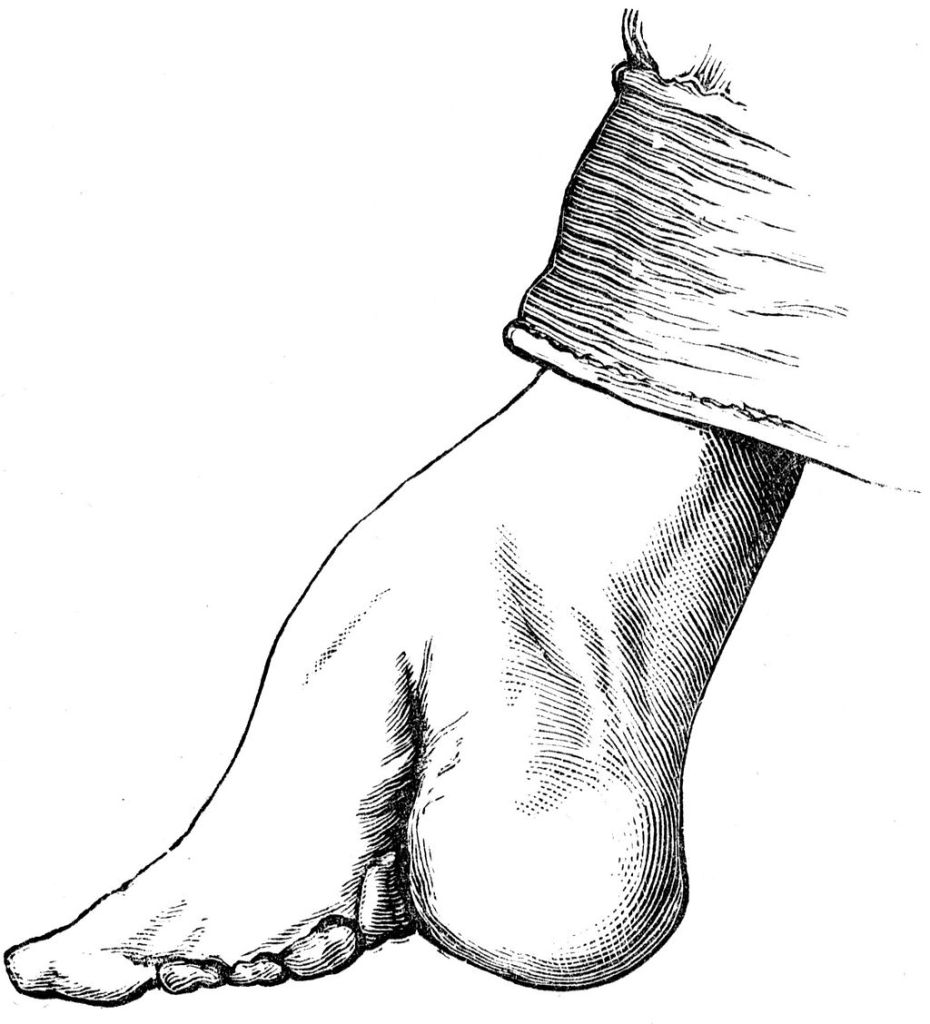

First, clip the nails as short as possible. Or better yet, just remove them. Less chance of infection that way. Then bend the four small toes under toward the sole of the foot. My sources vary on whether the foot is actually broken to achieve this, and I think that’s probably because the experience varied too. Take a long narrow binding cloth and wrap it tightly to keep it all in place. You should wrap so tight as to cut off circulation. The flesh will die, but that’s good. The less flesh, the smaller the remaining foot will be. Every three or four days remove the bandages. Since the foot is rotting away, there will be pus and blood. Wash it all off and bind it up again, each time getting progressively smaller (Wang, 4-6).

The entire process takes about two years. You are finished when you have achieved feet that are so small they look like a mere extension of the leg. Three inches long is the ideal often mentioned in the records. There will be only one visible toe, since the others have been tucked underneath. The arch of the foot is so high it is actually called cleavage, since it doubles back on itself.

The Chinese called these feet lotuses, since they reminded them of a flower. Also, they are reminiscent of a deer’s hooves (Wang, 12). Also, some have pointed out that they have some similarities with male genitals, though if you ask me, the resemblance is not that strong. It’s only noticeable if you’ve already got phalluses on the brain. As a great many of the source authors most certainly did.

An oversize or badly shaped foot meant the girl was lazy, impatient, and weak. Not the qualities you want in a wife. A loving mother had to teach her daughter to endure pain. Life would be full of it, after all. So mothers would often say a child’s least favorite words: you’ll understand when you’re older. In this case, mother was frequently right. Bound feet were so essential to marriage and social status that many women were grateful to their mothers for this childhood trauma (Wang, 19).

Once the process was complete, bound feet continued to need care. Remedy books contain recipes for foot washing solutions, right alongside the pimple creams and other beauty products. When badly cared for, bound feet smelled like rotting flesh, but even when done well, bound feet had a particular odor, which many men found to work just like an aphrodisiac (Wang, 24).

Women often designed and sewed their own shoes. It was a chance to show off your fancy needlework, and you’d need a lot of shoes: partly for fashion, but also because the foot never went bare, not even while you slept. Part of the sexual attraction was the mystery of that which was glimpsed, but never seen. A bare foot was indescribably lewd. A woman washing her feet was a much repeated pornographic image.

There are some cases of women whose feet were bound so tightly they could not walk at all and had to be carried everywhere. But that was not the norm. Most bound-footed women did walk, although with a short, swaying gait that men found incredibly attractive. It was not dissimilar to the way women walk in high heels, though it was considerably more permanent.

Some of the sources (including old Chinese ones) say that the purpose of footbinding was to keep women unable to work. All I can say is, if that was the intent, then it largely failed. Of course Chinese women worked. Like women in all cultures, they worked on textiles: spinning, weaving, and sewing. It is true that much of that work can be done sitting down. That doesn’t make it not work. But Chinese women also cooked, laundered, cleaned, bought and sold goods, created goods, and in some cases worked in the fields. Bound feet did not eliminate the need for those things. They just made it even harder than it needed to be. Very few women had the resources to sit around and do nothing.

Footbinding probably did begin as a marker of social class, for women whose main duty was to be beautiful. But it didn’t stay there. At its height, it was practiced by nearly 100% of Han Chinese families, and maybe 40% of all the ethnic minorities. That’s hundreds of millions of women who got up every day and worked hard to take care of their families, all while standing on bound feet.

The Campaign Against Footbinding

By this point you may be asking yourself: wasn’t anyone saying this was not a good idea? And the answer is yes.

The Qing dynasty emperor made footbinding illegal in 1664. Not surprisingly, he wasn’t a member of the ethnicity that had popularized the practice. The Qing dynasty were invaders from Manchuria. However, there was so much backlash he was forced to reverse the law four years later. The Han Chinese writers who recorded this saw it as a victory for Chinese women. They were less pleased about themselves and their masculinity: they were still forced to cut their hair to Manchu regulations (Wang, 34). If you ask me there is a big difference between cutting your hair and crushing your foot, but they didn’t ask me. Even Manchu women were soon jumping on the Chinese bandwagon (Hong, 50).

It was during this very same dynasty that footbinding moved from high urban fashion to an expectation for ordinary women (Ko, 132). It did that so completely, that when author Li Yu wrote a guidebook on how to select concubines, his cultural reference point was that binding feet is natural. It’s the unbound foot that is unnatural (Ko, 154). It’s a very twisted piece of logic, but he wasn’t alone in viewing the world that way.

The 18ᵗʰ century saw a few intellectuals begin to criticize the practice, even a very rare one from a woman. She was refused in marriage because her feet were unbound, and she wrote a poem in defense:

Three-inch bowed shoes did not exist in old times,

And Bodhisattva Guanyin had her feet bare to be adored,

I don’t know when this custom began;

It must have been invented by a despicable man.

(quoted in Wang, 35)

But that view was way outside the mainstream. Most women were proud of their beautiful, tiny feet.

The criticism intensified in the 19th century, largely because there was now an external factor. China had been aware of the Christian West for centuries. but China had been so strong itself that Western ideas were ignorable. The 19ᵗʰ century would see that overturned. Christian missionaries came in with the goal of converting a great nation. Religiously, they were not all that successful, but they did have an outsize impact on culture (Hong, 5).

In the West, the Christian church is not viewed as a great promoter of women’s rights, but in fact its record is mixed. It was certainly more feminist than mainstream China. Protestant Christians, for example, believed women should read. How else could they read the Bible? Both cultures stressed that women should be obedient to the men in their lives, but the Christian church always placed itself above that rule. There are quite a few Catholic saints’ lives where the girl was told to get married, but she loved God more so she ran away to the church and lived a life of virginity and that proved how holy she was. You might say that’s not much of a choice, but it is a little of a choice. For Chinese girls, obedience to her elders was always the prime virtue, no matter the cost to herself.

Missionaries in China reported that almost none of the Chinese women could read (Hong, 53), and missionaries were utterly horrified by footbinding. They opened schools for girls but found many girls couldn’t walk well enough to get there and if they did get there, they couldn’t do the physical exercises that were now part of a Western education (Hong, 55). Therefore, the missionaries began to campaign against footbinding.

The Chinese intellectuals were a little embarrassed that foreigners had thought of schools for girls before they had done it themselves (Hong, 62). But they were all in on the anti-footbinding campaign. However, their order of priorities was a little different. The missionaries were primarily interested in education. Footbinding was secondary.

For a growing number of Chinese reformers, footbinding was more important than education. It had not escaped their notice that China had once been the center of the world, the envy of all who saw her, but that was no longer the case. They had lost that preeminent position, and they were eager to get it back.

Here’s a quote from one reform scheme:

Foreigners laugh at us . . . and criticize us for being barbarians. There is nothing which makes us objects of ridicule so much as footbinding . .. The bound feet of women will transmit weakness to the children, weakening the bodies of healthy generations . . . When the weakness becomes inherited, where shall we recruit soldiers? Today look at Europeans and Americans, so strong and vigorous because their mothers do not bind their feet and, therefore, have strong offspring. Now that we must compete with other nations, to produce weak offspring is perilous.”

– (this is a mix of the two translations, quoted in Hong, 63, and Wang, 37)

Since Chinese women had been footbinding for almost 700 years, including at times when the West was sailing across unsailable oceans on the merest chance of maybe getting to China, it’s a little interesting that footbinding is suddenly to blame for China’s decline. But we do have the crux of the matter here in this quote. Chinese men were now, belatedly, ashamed. They wanted the respect of the West. And they had realized that as long as Chinese women were hobbling around on bound feet, they weren’t going to get that respect. It doesn’t seem to be about saving little girls from pain.

As the campaigns grew more urgent, the Dowager Empress Cixi did indeed forbid footbinding in 1902. But there wasn’t much enforcement.

The first leader to try enforcement was Yan Xishan of Shanxi from 1917-1922. He made footbinding illegal, and he meant business. He insisted that police visit all homes and do regular inspections, collecting fines for any illicit footbinding.

Now just think through what this meant. Remember that feet were the center of erotic interest in Chinese culture. So an official inspection was the equivalent of having your local police officer show up at your door and insist on seeing all the females in the house, naked.

This would not go over well in my own country, and it did not go over well in Shanxi. The local population was outraged and accusations of abuse skyrocketed (Ko, 56-57).

Now I wondered whether any girls or women thought enduring a little voyeurism was a worthy tradeoff to avoid the pain of footbinding. As usual, we don’t have many records from their perspective, but for the most part, that seems not to be the case. Unlike their esteemed leader, they were largely not in a position to either know or care what a lot of Western foreigners thought. What they knew was the standard that had been thrown at them for generations: only servants have big feet, no girl with unbound feet will ever get married, you are ugly, everyone will make fun of you.

When the reformers told women how to handle their own bodies, they largely didn’t say “unbound feet are beautiful just as they are, and we’d like to save you from the enormous pain of footbinding.” Nope, they largely stuck with the shame rhetoric. Yan Shanxi himself traveled around giving speeches and here’s a taste of what he had to say:

“Look at you! Don’t you have any self-respect? What are you doing this for, harming your own body and causing others to look down on you?”

(Ko, 59)

You can see why this fell a little flat. As far as most women knew, the truth was exactly the opposite. We don’t have good documents on how well Yan Shanxi succeeded, but there is some indication that patriarchs of the families just paid the fines. It didn’t stop footbinding.

Besides the opinion of foreigners, there was soon another reason to add fire to the anti-footbinding campaign. This was the era of rising Marxist ideas, and whether you leaned toward communism or capitalism, it was no longer elegant to pretend you didn’t need to work.

It was against this backdrop that intellectual Liang Qichao wailed that “All 200 million of our women are consumers; not a single one has produced anything of profit… No wonder men keep them as dogs, horses, and slaves” (Ko, 21).

This is such an outrageous claim that I’m tempted to wonder if Liang Qichao had the foggiest notion about who made and laundered his clothes, cooked his meals, cleaned his house, or cared for his nine children. Yes, nine. At least according to Wikipedia. I didn’t investigate that point any further, but I am guessing that if 200 million women in China had actually stopped producing, he would have noticed in a hurry.

Idiots aside, the point remained that in the emerging China, efficiency was the new beautiful, and efficiency doesn’t include bound feet.

The trouble was that even if parents stopped binding the feet of their girls, it would still leave untold millions of women whose feet were already bound. China would have this embarrassing reminder of their past for decades.

Eventually, public opinion swung so far in the opposite direction that footbound women were publicly ridiculed or attacked on the streets. Some were abandoned by their husbands for the very quality that had once made them a good match (Wang, 41). Reformers insisted that women let their feet out. They called it liberating the foot. Most of the instructions took it for granted that the foot would go back to its natural shape if women would just let it. Of course, that wasn’t true. Bound feet could come out a little, but they would never be the same as an unbound foot. And it was actually harder to walk on a liberated foot than it was on a bound one (Ko, 48-49, 11). For older women, the damage was permanent.

When the Communists came into power, they stamped out footbinding for good. The last reported case was stopped in 1957 (Ko, 4), but the last factory making shoes for previously bound feet did not close until 1999. Scattered older women with bound feet certainly still lived in the early 2000s and possibly still do (Ko, 9). I found that very difficult to verify for the current year.

How Could Footbinding Have Happened?

Since I (and I presume you) are far removed from the practice of footbinding, this whole 700-year episode is a little hard to fathom. It looks like horrifying child abuse in pursuit of something that isn’t in any way beautiful. How could any mother have done it to her own child? How could women let it continue for so long? Why would a whole culture decide to cripple half their population?

Some writers have pointed out that nearly every culture practices some form of self-mutilation in the pursuit of beauty. Some of the ones currently in vogue in my own culture are piercings, tattoos, extreme dieting, and plastic surgery. If you’re bristling right now, I hear you. There’s a huge difference between any of those things and footbinding. Differences like anesthesia, and age of consent, and long-term consequences, among others. These things are not trivial.

Western theorists have loved to come up with other explanations. Sigmund Freud said it was man’s projections of his castration anxieties onto the female body (Ko, 2), which I don’t accept at all. Sociologist Thorstein Veblen said that it was a matter of conspicuous consumption. The women of the leisure class had to display their ability to not work by being physically incapable of working (Ko, 2), which may well have been how it started as I mentioned, but hardly explains its extent. The Marxist-feminist answer is that footbinding allowed men to pretend that women’s labor was useless by making them appear incapable of working, while the same men benefitted from the labor women actually were doing anyway (Ko, 3).

We don’t get to run history like a science experiment, so we will never know for sure how footbinding would have turned out if, for example, women had held any property rights in China. Or if women had been educated enough to record their own painful experiences in large numbers. Or if women had had viable career options other than a good marriage. Or if Confucianism had not put such a heavy stress on obedience. Or if any one of a number of conquerors of China had said this is not beautiful and footbinding really will stop now. Or if that favorite concubine of whatever powerful man started this had just had really outrageously big feet instead of small ones. Really, so many possibilities for stopping this in its tracks, but none of them happened.

There are no easy explanations, but if you, like me, are glad that footbinding is over, take a moment to stretch your feet and wiggle your bare toes. It’s a beautiful feeling, isn’t it?

Selected Sources

Hong, Fan. Footbinding, Feminism and Freedom. Routledge, 3 Apr. 2013.

Ko, Dorothy. Cinderella’s Sisters : A Revisionist History of Footbinding. Berkeley (Calif.) ; Los Angeles (Calif.) ; London, University of California Press, 2005.

Wang, Ping. Aching for Beauty : Footbinding in China. New York, Anchor Books, 2002.

[…] be particularly new. Throughout history and around the globe, women have routinely squeezed, bound, crushed, tweezed, poisoned, pricked, and stretched various portions of their anatomy, sometimes with […]

LikeLike

[…] this same myopia also allowed the mistreatment of the ordinary women. Such as when the early 20th century Chinese intellectual Liang Qichao wrote, “All 200 million of our women are consumers; not a single one has produced anything of […]

LikeLike

[…] https://herhalfofhistory.com/2024/08/15/13-4-chinese-footbinding/ […]

LikeLike