Surely I am not the only woman who has ever eyed the razor and the shaving cream and wondered “Why?” I can’t speak to your personal motivations, but I can tell you that women have been questing for hairlessness for a very long time.

Hairless in the Premodern World

Egyptian, Greek, and Roman art all suggest that body hair does not exist. It doesn’t get depicted. Often not even for the men. Whether and how the living, breathing Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans accomplished that is less obvious, but there are some hints.

Ovid, the Roman poet (43 BCE to 17 or 18 CE), mentioned in his advice on love for young maidens that “How near I was to warning you, no rankness of the wild goat under your armpits, no legs bristling with harsh hair! But I’m not teaching girls from the Caucasian hills” (Ovid, Art of Love, Book III, Part III).

The Caucasian hills were out in the hinterlands, you understand, amid the rustics who are only one step above the actual rampaging barbarians beyond the empire. The implication is that good, upstanding Roman girls aren’t so hairy. I’m guessing that wasn’t a matter of genetics. It was more likely to be a matter of hard work, possibly painful work.

Seneca, the Roman letter writer who lived shortly after Ovid, mentions that the public baths were filled with the cries of professional hair pluckers. (This is a career path I never even considered.) There are an astonishing number of tweezers found in Roman archeological sites like Wroxeter in England (Henderson, Brown, Parker). Both men and women attended Roman baths, and presumably a professional hair plucker is not going to be picky about the gender of his or her clientele.

The Babylonian Talmud (written in the 3rd to 6ᵗʰ centuries CE) mentions that women use oil of immature olives as an agent for removing hair (a depilatory, if you’re familiar with that word) (Menachot 86a). It doesn’t say which part of their anatomy was receiving the treatment.

An 11ᵗʰ century medical textbook written by an Italian woman places great emphasis on recipes for depilatories, many of which claim to be of Muslim origin. Here’s the first one:

“In order that a woman might become very soft and smooth and without hairs from her head down, first of all let her go to the baths, and … let there be made for her a steambath… Afterward let her also anoint herself all over with this depilatory, which is made from well-sifted quicklime. Place three ounces of it in a potter’s vase and cook it in the manner of a porridge… Take care, however, that it is not cooked too much and that it not stay too long on the skin, because it causes intense heat.”

(Gilmore, 167)

Quicklime, by the way, is calcium oxide, which is made by heating up limestone or seashells. It’s caustic. So it’s not surprising that this recipe concludes with another recipe for burn relief.

If you don’t like that option, there are others, like the one that says “In order permanently to remove hair, take ants’ eggs, red orpiment, and gum of ivy, mix with vinegar, and rub the areas” (Gilmore , 175). I had to look up orpiment. It means arsenic.

Two Roman, one Jewish, and one medieval reference is hardly comprehensive, but that’s not surprising. Would a biography of your life mention your hair removal practices? I’m guessing not. It’s just not in the record for the most part.

Nothing changes as we get into later eras. Noticeable body hair on art depicting a female continues to be rare. Take Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, for example. Other than her scalp, she is utterly smooth everywhere we can see. Which admittedly is not quite everywhere, but almost. When Botticelli imagined Beauty personified, he didn’t imagine body hair. Talk about your unrealistic beauty standards.

(Wikimedia Commons)

A 1540 English book also recommends quicklime and arsenic. Or maybe nightshade to “anoint so far the place that ye would have bare from, hair, as it liketh you” (Rosslin, 199). I could go on, but in truth the sources are spotty about the details. A recipe is all very well, but how many women were using it? And how often? And on what portion of their anatomy? And did it work? And did all the poison kill anyone? The sources are mostly silent on these questions.

So I don’t know what your average woman was doing this on a regular basis, but there are occasionally some hints to suggest that some of them were not doing all of that.

Early American authors commented a lot on how hairless the native tribes were, but they were divided on whether that was biological or because of a culture of plucking any hair that appeared. Most of the speculation was about men’s beards, but not all. The women were mentioned too, which suggests that being hairless was foreign to these writers of European descent. It was worth mentioning. And it would only be that if the European women did leave some body hair (Herzig, 29). An opposite inference than the one we get from the art.

The Birth of Commercial Hair Removal

Home remedy manuals and cookbooks continued to give various recipes for hair removal tonics right up until about the 1850s and 60s. Even then the change was not that women stopped wanting them. It’s just that they stopped mixing them. Now they could just buy their poison instead of cooking it (Herzig, 40-41).

It also means we can now look to the advertisers for more information. Ads still don’t tell us what the average woman actually did, but they do tell us what manufacturers hoped they would do. What we find is that the hair they are concerned about is on the face. This was an era when men were men and women were women. So the occasional facial hair on a female was really bad. Ads routinely inform women that facial is the greatest disfigurement a woman could possess (Herzig, 42; Sears Roebuck, 34). Way to sell based on insecurity.

Clearly many women were concerned about that occasional hair, but a few others were taking the opposite approach. The story of Bearded Ladies, from pharaohs to performers, is going to be a bonus episode, out this week. It is accessible either through Patreon or through Into History, depending on what level you sign up for either place.

Most women, however, did not aspire to be bearded ladies. Facial hair was a problem. It’s not surprising that hair on other parts of the body got less attention. The fashions meant that your other hairy bits weren’t generally seen. Nevertheless, the quest for hairlessness was about to receive a big jolt from an unlikely direction. Science was about to get involved.

Evolution and Hairlessness

In 1871, Charles Darwin published The Descent of Man, and he said that humanity’s relative hairlessness was evidence of sexual selection in our evolutionary progression. Fur has enormous advantages. It keeps you warm when it’s cold, dry when it’s wet, unburned when it’s sunny. Plus your baby can cling to it, leaving your arms free. In fact when it came to hairlessness, Darwin couldn’t think of any evolutionary advantage at all. It was a dumb idea that Nature would never have thought of herself, so it must have been early humans who selected it. Out of choice. Because they found it sexually attractive (Herzig, 57; Stenn, chapter 1). To the average reader, this meant science has proved that body hair is unattractive.

It is true that not everyone agreed with Darwin. They pointed out other possible explanations and several logical stretches, but more were eager to hop on the bandwagon. By the dawn of the 20ᵗʰ century, hairiness didn’t just mean ugly. It also meant you were lower on the evolutionary ladder. Quite possibly you were mentally incompetent or a criminal or a sexual deviant (Herzig, 56, 57, 73; Stenn, chapter 1).

Now what I don’t fully understand here is why that didn’t apply equally to men and women. We’re all evolving together, right? Men also vary in the amount of body hair they grow, but as far as I can tell, they just made their choice about beard or no beard according to the fashions of the day, and that was about the limit of their concern over the issue. It was women who were going to doctors and magazine editors that a few errant hairs on their chin were so distressing that they wanted to kill themselves (Baum, 104; Herzig, 75). Scientists were busy writing papers on how the mostly male prisoner populations had more hair than your fine upstanding citizens, but it didn’t lead your average man to do anything about his chest or underarm hair. Not that gets mentioned in my sources anyway. Women were a totally different story.

My sources didn’t discuss why women stressed more, but I have a theory. My theory is that it’s all bound up in which gender has the greatest need to make themselves sexually attractive. In many bird species it is the male who goes all out for frou-frou: colors, plumes, sweet dance moves. That’s because he has to please a picky female, who may or may not look on him with favor. In humans of this period, it was just the opposite. Many men could afford to be picky. Most women could not, so it was women who had to go all out on the sexually attractive gig. Whether I’m right or wrong about why, body hair was increasingly frowned on for women and those recreant hairs were about to meet their fate.

Shaving for the Masses

I have not yet mentioned shaving as a solution for women and that’s because it wasn’t a solution. Shaving certainly existed, but it was done by professionals: men who could carefully wield a very sharp blade and meticulously maintain that sharp edge afterwards. Clean-shaven men usually had a servant who did this for them or they went to a professional barbershop. There were few to zero equivalent establishments for women.

By World War I, the Gillette company was selling a safety razor, one with a guard and a handle and a disposable blade. The shape and function was much like the ones sold today, but it wasn’t yet plastic, and you didn’t yet throw away the whole thing. You just popped out the blade and inserted a new one. That was much safer and easier to maintain than the razors that men had used for hundreds of years.

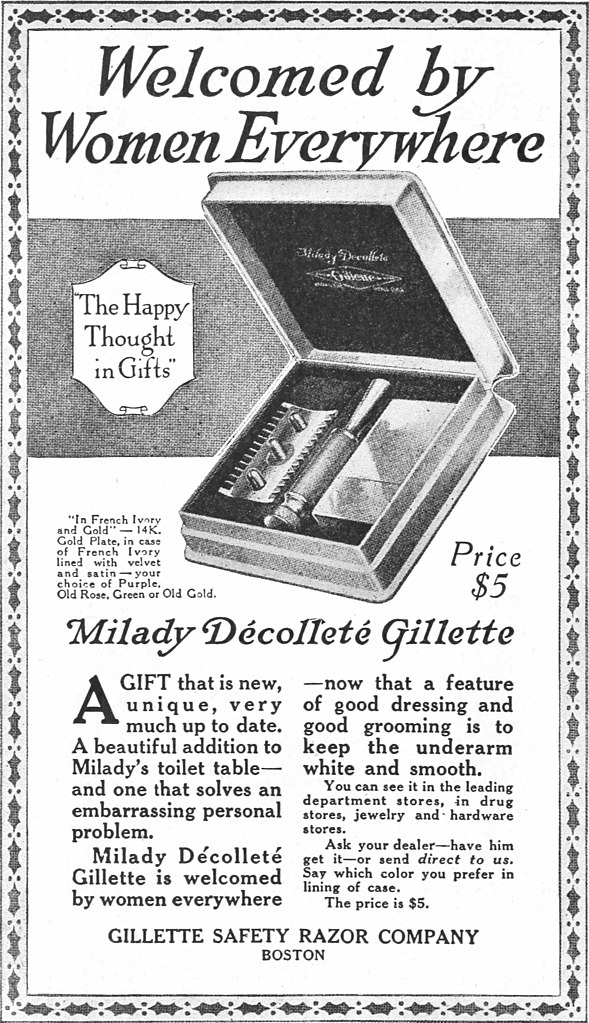

Gilette’s original safety razors were for men. Men were the target audience for anything resembling shaving. But in 1915, Gillette introduced the Milady model, which was exactly the same thing, except smaller. Gillette pushed ads in popular women’s magazines like Harper’s Bazaar and McCall’s, and the ads are clearly targeting underarm hair. It was genius marketing because facial hair only appears on a small subset of women. As far as I know, we’ve all got it in the armpits. If that is suddenly a problem, then every last one of us needs a Milady razor and a regular supply of refill blades (Riordan, 137-138; Herzig, 124). That’s a lot of potential customers.

(Wikimedia Commons)

At the same time, dresses and bathing suits were going sleeveless, which made your armpits more publicly visible than they had ever been before. Everyone would know that you had underarm hair. A thing they could only wonder about before. Also private bathrooms were multiplying, indoor plumbing included, which meant it was more and more possible to discreetly remove those hairs (Herzig, 119), with no need to embarrass yourself in a public establishment.

Leg hair was less of a concern. They were still covered. The hemlines were rising, but the stockings were thick. No one was going to see any hairs under there.

But that was temporary.

A Multiplicity of Options, an Increasingly Desperate Quest

The 1920s definitely had shorter skirts and thinner stockings. By this point, hairiness was enough of a concern that women had a dizzying array of options for removing it. Besides shaving, you could go for abrasion with pumice stones, sugar and paste solutions, or a thing called Velvet mittens. Or you could go for pulling the hair out with tweezers and waxes. Or you could go for chemical treatments like peroxides, sulfides, or thallium. Or you had electrolysis and x-ray treatment (Herzig, 79-82).

There were so many options because none of these options were ideal. You were choosing between the varying money, time, expense, and health risks. And there were health risks. Death by hair removal was a real possibility with some of those treatments, especially the thallium and the x-rays. Risk did not change the desperate desire to be less hairy.

A 1922 beauty book said, “Lucky the woman who has no superfluous hair; let the rest of her sex get rid of it as best they can” (Riordan, 143). Since superfluous now meant any underarm or leg hair at all, I’m pretty sure no woman counts as lucky there.

Then World War II came along and rationed nylon for stockings and poof, there went any hope of just concealment (Herzig, 126). The war ended, but stockings never went back to the way they had been before. By 1964, 98% of all American women aged 15 to 44 routinely shaved their legs (Herzig, 127; Riordan, 143). I’m afraid I don’t have data for the rest of the world for this same time period. I’m betting it was a lower percentage, but not zero.

Women generally chose shaving because it was the cheapest, most private, and least painful of the options. But it has to be done over and over and over, as I’m guessing many of you know.

The plastic disposable razor came to market in 1975. Now you could throw away the whole razor, not just swap out the blade (Herzig, 128).

The 70s also saw a second wave feminist fight over body hair. Some feminists ranted about how a patriarchal society was forcing women to waste their time, money, and health on body hair that was perfectly natural and not a problem just the way it grew. Other feminists looked on with irritation and said why are you wasting your rants on leg hair when women need equal employment opportunities? (Herzig, 130). Priorities here, people!

By and large I’d say that second camp of feminists won. Women do have better employment opportunities now. Meanwhile, the quest for hairlessness has only intensified. One researcher found that “Between 92 and 99 percent of women in the US, UK, Australia, New Zealand, and much of western Europe regularly remove their leg and underarm hair” (Fahs). Hair removal is also on the rise in places like China and Japan (Fahs).

In the 90s laser hair removal became a possibility. (X-ray clinics had long since gone illegal. The atom bomb was a bit of a wakeup call. People were less eager after that.) Also in the 90s came a new dream: gene therapy. Maybe we could just not grow body hair in the first place! (Herzig, 153, 172) So far that one has proved hard to implement.

In the 2000s, women were told that their pubic hair also needed to go. Some Muslim women had been doing that for a while already, but it was in the 2000s that it became more generalized. Pubic hair hardly ever got a mention or a depiction in the past. Except in pornography, where it was generally considered a good thing. Very erotic. It is true that for all the millions of nude women in the more respectable history of art, there is remarkably little pubic hair, but often that can be attributed to discreet leg placement, or a coyly twisted body, or the oh-so-casual fall of one scrap of fabric trailing from a nearby cupid.

I sure hope that’s the explanation because the available methods for removing pubic hair in the pre-razor world sound excruciating. Then again the very popular Brazilian wax can also be excruciating. I asked Google about that, and the AI assistant informed me that it’s not as bad as falling off a truck, so there you go. A ringing endorsement. That same study that I previously mentioned about the leg and armpit hair, they found that 50-98% of these same women also remove some or all of their pubic hair (Fahs).

What I’m curious about is what happens next. Because in the long-standing quest for less and less body hair, I don’t see any further frontiers to conquer. No hairy bits are left.

Except the scalp, of course, and that is an entirely different matter. I’ll talk about that next week.

Selected Sources

Baum HC. “The Etiology and Treatment of Superfluous Hair.” 54 (1912):104–106. doi:10.1001/jama.1912.04270070105008

Brown, Mark. “Romans, Lend Me Your Shears: Empire Brought Hair Removal to Britain, Says English Heritage.” The Guardian, 24 May 2023, http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2023/may/24/body-hair-removal-what-romans-did-for-us-english-heritage. Accessed 31 July 2024.

Fahs, Breanne. “Can Everyday Body Hair Practices Have Revolutionary Implications?” University of Washington Press Blog, University of Washington Press Blog, 15 June 2022, uwpressblog.com/2022/06/15/can-everyday-body-hair-practices-have-revolutionary-implications/#_ftnref1. Accessed 8 Aug. 2024.

Gilmore, David D.. The Trotula: A Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine. United Kingdom: University of Pennsylvania Press, Incorporated, 2001.

Harrison, Dora. Combined Bust Form and Armpad. 23 Aug. 1907, ppubs.uspto.gov/dirsearch-public/print/downloadPdf/0861115. Accessed 6 Aug. 2024.

Henderson, Jeffrey. “The Epistles of Seneca: Epistle LVI.” Loeb Classical Library, http://www.loebclassics.com/view/seneca_younger-epistles/1917/pb_LCL075.373.xml. Accessed 31 July 2024.

“Menachot 86a:1 from the Babylonian Talmud.” Www.sefaria.org, http://www.sefaria.org/Menachot.86a.1?lang=bi. Accessed 30 July 2024.

“Ovid (43 BC–17) – Ars Amatoria: The Art of Love, Book III.” Www.poetryintranslation.com, http://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Latin/ArtofLoveBkIII.php.

Parker, Christopher. “The Ancient Romans Used These Tweezers to Remove Body Hair.” Smithsonian Magazine, 13 June 2023, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/ancient-roman-tweezers-hair-removal-180982364/.

Riordan, Teresa. Inventing Beauty : A History of the Innovations That Have Made Us Beautiful. New York Broadway Books, 2004.

Rösslin, Eucharius., Jonas, Richard., Raynalde, Thomas. The Birth of Mankind: Otherwise Named, The Woman’s Book : Newly Set Forth, Corrected, and Augmented : Whose Contents Ye May Read in the Table of the Book, and Most Plainly in the Prologue. United Kingdom: Ashgate, 2009.

Stenn, Kurt S. Hair – a Human History. Pegasus Books, 2017.

[…] new. Throughout history and around the globe, women have routinely squeezed, bound, crushed, tweezed, poisoned, pricked, and stretched various portions of their anatomy, sometimes with permanent […]

LikeLike