Like this episode on hair, this episode comes with a disclaimer: the history of makeup could be its own podcast, and I should not be the host. I do wear makeup, but only a little, and I choose it mostly on price. As in the lowest price I can find. The cosmetics aisle is filled with products I know nothing about, and I have no plans to change that.

But I often feel that that makes me an outlier as a woman. Even as a historical woman. So let’s see what we can do, historically-speaking.

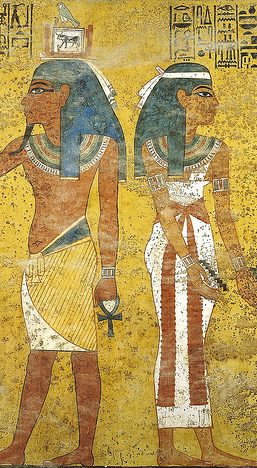

The first thing to know is that there is no logical reason why makeup should be a gendered thing at all. In ancient Egypt, it wasn’t. Both men and women there used kohl as eyeliner (Tyldesley, 159). So much I already knew. What I didn’t know is what kohl actually is.

Turns out kohl is not a specific substance at all. Egyptians used a range of things like ash, ochre, copper, malachite, lead, and burnt almonds. These were stored in small containers and moistened with water or oil before applying them with a little spoon or spatula (Eldridge, 69). This was very, very common. We know it not only from paintings of people but also because archeology turns up kohl containers a lot. The eyeliner was applied both above and below the eye, often with a bold line out the side. Looking natural was not the point (Tyldesley, 159).

(Wikimedia Commons)

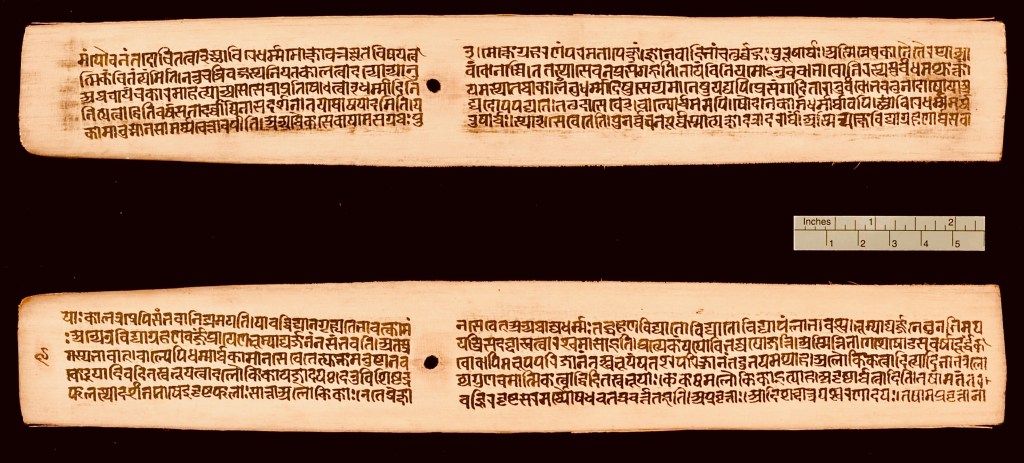

Ancient India also knew about cosmetics, and it was also ungendered. The Kama Sutra was written somewhere between 600 BCE and 300 CE, and it says

Now, good looks, good qualities, youth, and liberality are the chief and most natural means of making a person agreeable in the eyes of others. But in the absence of these a man or a woman must have resort to artificial means, or to art, and the following are some recipes that may be found useful.

Many of the following recipes are not cosmetics at all, but straight up magic charms. Like the one that says “If the bone of a peacock or of an hyena be covered with gold, and tied on the right hand, it makes a man lovely in the eyes of other people.”

But one of the recipes is a cosmetic. It’s for mascara. It says:

“If a fine powder is made of … plants, and applied to the wick of a lamp, which is made to burn with the oil of blue vitrol, the black pigment or lamp black produced therefrom, when applied to the eye-lashes, has the effect of making a person look lovely.”

(all quotes from Kama Sutra, part 7, chapter 1)

Based on this translation, it sounds to me like using that mascara was something both men and women might do. It is true that I have found ungendered words like “person” to be unreliable in translations before, and I don’t have the language skills to check the oldest extant version of the Kama Sutra. But I would think that if there were any doubt about it, an Anglo translator like the one I’ve just quoted, would have assumed mascara is for women, not men. He didn’t.

Lamp black, by the way, would remain a cheap and accessible makeup ingredient for centuries. Even millennia.

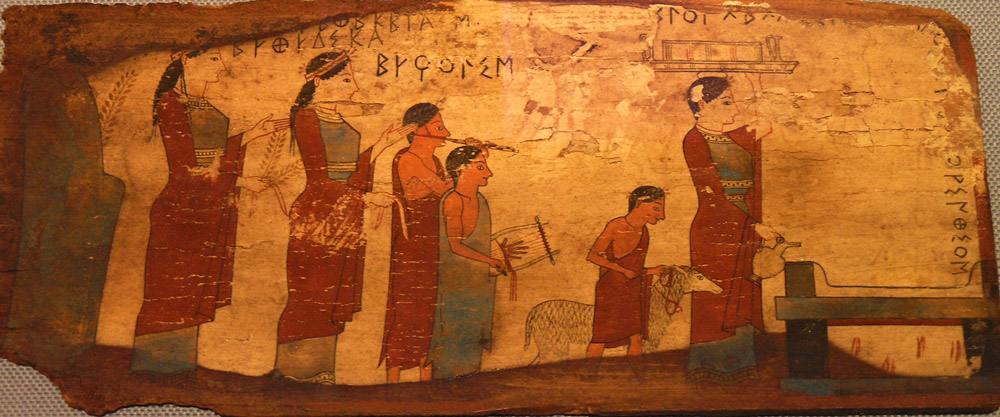

Greek and Roman Cosmetics

The ancient Greeks were a lot less interested in enhancing the eyes. They preferred to enhance the skin. As in they wanted it whiter.

The desire for white skin is a super touchy issue in the modern world, and rightly so. It is all bound up in the question of race and poverty and a long, heavy history of exploitation.

Athens didn’t have that same cultural baggage. They did have slaves, but it wasn’t based on race. It was slavery of non-citizen foreigners. Some of them may well have come from sub-Saharan Africa, but others came from the very Caucasian north. So when Athenians wanted whiter skin it was not because they needed to distinguish themselves from the lowest of the low. That rationale will be saved for later in world history.

In my experience, beauty standards frequently don’t need a rationale to exist, but if you want one anyway, then you can say that whiter skin was a sign of wealth: to be able to loll around indoors, rather than work outside in the sun all day. Only rich people had that option. So this is pale vs. tanned skin, rather than an ethnic white vs. black skin, though there is no denying the standard was harder on those who were born with even slightly darker complexions.

Athenians managed their white skin with lead-based cosmetics. They had a lot of lead available. Much of their wealth came from the Laurion silver mines. Generally speaking, silver and lead exist together and are mined together (Stos-Gale). So lead is a byproduct of silver mining.

Lead is toxic, and yes, the Greeks knew that. But lead in its pure form doesn’t easily get absorbed through the skin. Taking it orally is most obviously bad. Taking it topically does make for a nice, white foundation on your face. The trouble is that you start mixing it with things like vinegar to get a smooth application. Whatever you add to it changes the chemical composition, and then it actually might get absorbed through the skin after all. Women appear not to have cared that much. Lead foundation would remain a staple cosmetic ingredient for centuries.

The Greeks had a couple other cosmetic innovations that would stick around too. As far as I can tell, they are the Westerners who made it a gendered thing. There is one reference in Plato that implies that some men used cosmetics (Plato). Every other ancient Greek reference is about women. Women are putting white lead on their faces and rosy alkanet juice on their cheeks and the men don’t like it. No, indeed, they do not.

In one dialogue by Xenophon, the husband says to his wife:

“Tell me, my dear, should I be more worthy of your love… by disclosing to you our belongings just as they are, without boasting of imaginary possessions… or by trying to trick you with an exaggerated account, showing you bad money and gilded necklaces?”

He goes on to explain that her makeup is just as terrible. He brings wealth to the marriage. She brings beauty. If her beauty isn’t real, then that’s nothing but deceitful trickery, and “people who live together are bound to be found out” (Xenophon, chapter 10).

The other Greek writers take the same view. One historian says he could not find a single Greek source that said anything good about makeup at all (McDaniel). Nevertheless, Greek women must have been wearing it, or the elite men wouldn’t have needed to write against it, right?

The situation was not much changed in Roman times. White skin was still prized, lead-based paint was the way to achieve it, and the men complained about deception (Johnson, 3, 6). Seneca, Plutarch, Plautus, and Pliny all have negative things to say about women and their makeup (Johnson, 6).

The exception is Ovid, same guy I talked about last week. He’s a comic writer, which often means he says things that other people won’t. He is largely (but not always) in favor of cosmetics. He agrees that they are a deceit, of course they are. But he, for one, is more than willing to be deceived in the pursuit of beauty (Johnson, 17). To this end he gives multiple recipes for face cream to make your complexion shine, and he suggests poppies to make your cheeks rosy (Ovid, Medicamina).

In a different work, his instructions are less clear, but the goal is the same: “she who does not blush from true blood, blushes by means of art” (Ovid, Ars Amatoria).

So Ovid is all in favor of cosmetics, provided he does not have to see how it’s done, for “it is proper that men remain ignorant of many things” (Ovid, Ars Amatoria).

What is fascinating about Rome is that not only do we have the recipes and the moral hand wringing, we also have actual face cream. Empty containers are a dime a dozen in archaeological sites, but not all of them are empty. At a dig in London, a jar of 2,000-year-old face cream was found. You can still see the finger swipes inside it. On analysis, it was found to contain tin, not lead. Which is great. Tin isn’t as toxic (as least as far as I could tell in my brief Internet search). So this was maybe the health-conscious version. The kind that usually costs more than your generic (Mansell, Simpson).

Chinese Cosmetics

Over on the other side of Eurasia, women were also using cosmetics. As per usual, my accessible sources on Asia are not as good as the ones on the Western world. I can find blogs and youtube videos, but they largely don’t cite their sources. We’re going to see what we can do anyway.

For starters there is a curious and unsettling similarity between Asian cultures and European ones. Both were going for whiter skin. There’s that uncomfortable subject again.

Chinese women pulled this off with rice powder (which sounds pretty innocuous to me). But also with white lead, the same as their European counterparts (Eldridge, 45).

What may be different is the degree. I am assuming that most Greek and Roman women were going for subtle and natural-looking. I don’t have any evidence for that, except that if they had not been, how could any man complain about being deceived? It’s not deception if you use so much makeup that it’s perfectly obvious what you have done. At some point it crosses over into straight up face paint or body art. It may be beautiful, but everyone knows your skin doesn’t grow like that.

Chinese paintings of women tend to be very idealized, with every female figure having essentially the same face. But by the Tang dynasty, which started in 618 CE, there are a few surviving pieces of art that suggest a few different makeup trends, and not subtle ones (Hinsch, 98). One is the use of rouge or blush, not just on the cheekbones but all over the entire cheek. A woman might naturally look like that if she just finished a marathon or has a health condition or maybe if she’s drunk, but since the court woman in the picture I’ve posted on the website is actually just playing chess, it suggests makeup.

In other pictures, the eyebrows look drawn on, not always where real eyebrows would fall. That could be a matter of the artist, rather than the woman, but it could also mean makeup.

(Wikimedia Commons)

And finally, there are sometimes designs that are definitely not natural. (Here’s where we are moving into body art.) You have probably seen bindi, most commonly a red dot on the forehead of Hindi women, though there are a variety of types. Some Chinese women of the Tang dyanasty had something similar, but it is not just a dot. It is often a flower, which is why it’s called a hua dian,

This much is explained in my less-than-ideal sources (Li, Felici) and confirmed by me looking at art from the Tang dynasty.

The sources go on to say that Chinese ladies of this period also give themselves dimples in a variety of shapes and also red crescents on their temples. I was not able to verify that for any paintings that I know came from the Tang dynasty. But I did find those crescents on paintings that came much later, including the picture of Empress Wu Zetian, which I used in episode 2.3. She has three dots for the hua dian on her forehead and three crescents on the temples. Empress Wu did live at the beginning of the Tang dynasty, but unfortunately there are no surviving portraits of her from that time period. The one I used for the episode was created after her lifetime, and for all I know it may reflect much later makeup trends.

(Wikimedia Commons)

I also have to say that I also found Tang dynasty paintings of women who didn’t seem to be doing any of the above. Which does make sense. Makeup trends come and go in the modern era, and some of us are very, very slow to catch on. It stands to reason that that may have been true all along.

Indian Cosmetics

My sources on India are also not ideal, but I can say that the bindi (that dot on the forehead) is very old. There is a piece of art depicting a woman with a bindi from about 200 BCE. Other sources make it clear that Indian women knew all about face creams and the like. What I don’t see in my one decent source is any hint that the purpose of the cream was to make the face whiter. Smooth, radiant, and luminous, yes. But not whiter. Also there doesn’t seem to be any clear distinction between the recipes for men and the ones for women (Patkar).

Medieval Cosmetics

If we return to Europe, I am on firmer ground.

The medieval self-help book for women who wanted to look good is called the Trotula, and it was written in the 12th century in Salerno, Italy. It was copied and translated and distributed all throughout the continent for centuries. Much of the Trotula concerns medicine and health concerns. The lines between medicine and cosmetics were not always clear (and sometimes still aren’t). But the final section of the Trotula is purely on cosmetics.

It is quite clear that southern Italy is a multi-cultural world, for several of the recipes are directly attributed to Muslim sources, with ingredients that your average European woman could not grow herself: frankincense, cloves, cinnamon. These things depended on trade networks.

But if you could get your hands on them, they were well worth it. The Trotula says so. It starts the cosmetics section by saying that “the face ought to be adorned, because if its adornment is done beautifully, it embellishes even ugly women (Green, 177).

No surprise, women are still whitening their faces, and they are still doing it with lead (Green, 163). But they also have a lot of other methods. In some ways, there was an advantage to being poor. If you couldn’t afford lead, you used chickpeas, barley, almonds, or milk—all of them much, much better for your health than lead (Eldridge, 53). Some of the recipes are very elaborate and took days to prepare and apply, so there was a cost even if you had all the ingredients on your own farm.

The Trotula also has recipes for lip gloss (Green, 185) and reddening the face (Green, 179). Enhancing the eyes seems to have fallen out of fashion.

(Wikimedia Commons)

Renaissance Beauty

By the Renaissance, trade was booming. Money and goods were more plentiful than ever before, and the publishing industry was happy to sell you printed instructions on how to be beautiful. In 1526, the first known such book was published, and it was aimed at working women (Burke, 6). It was true that most working women couldn’t read, but that was no impediment. Books were intended to be read aloud. Wealthy women were also interested. Caterina Sforza, countess and regent of Forlì, published her own book of beauty tips (Palmieri). It also contained instructions on how to poison people, so it’s an eclectic mix (Eldridge, 93).

By this point, race definitely was a factor in the desire for whiter skin. It doesn’t get mentioned a lot, but many European countries still had slaves in the Renaissance. That’s true even in the home countries. (Colonies were only about to get going.) Enslaving other Christians had long since been frowned on. So that meant slaves were coming from the Islamic world, and even farther abroad. These people generally had darker skin than Europeans, so it became important to distance yourself (Burke, 84). To emphasize that you are not one of them. Racism was not as deeply ingrained as it would become later, but it was ramping up, unfortunately.

White lead was so ubiquitous in Venice, that it became known as Venetian ceruse. It was worn by Elizabeth I of England and Catherine de Medici of France (Eldridge, 27, 58). Caterina Sforza knew there were alternatives to lead, and she said so. One of her recommended alternatives contains mercury, which is definitely toxic (Palmieri, 18). In fact, one court case involved a girl murdering her siblings by using her mother’s face cream as a salad dressing (Burke, 216). It was mercury-based. The kids died.

The publishing industry was also good at distributing the critiques of cosmetics. What I find interesting is that Greek and Roman men complained about deception, but Renaissance men had some different angles on which to base their criticism.

One was a genuine and completely valid health concern. One author said Venetian ceruse made women “withered and gray headed” (Lomazzo, 130), which is absolutely true. The problem with Venetian ceruse was that the more you used it, the more you needed to use it. Because it ravaged your skin (Eldridge, 50). It’s a seller’s dream, but only in a world without health and safety regulations.

Another complaint was the money angle. Expense was maybe all right for women who had money to burn. But working women did not. A printed tract of 1598 sniped that “if one sees a poor woman who has six pennies to her name, four of them are on her face” (Burke, 14).

Any of these genuine concerns could be mixed up with hyperbolic ranting, as was done by one author who said:

“The ceruse or white lead, wherewith women use to paint themselves was, without doubt, brought in use by the devil, the capital enemy of nature… For certainly it is not to be believed that any simple women without a great inducement and instigation of the devil, would ever leave their natural and graceful countenances, to seek others that are suppositions and counterfeits. . . . The use of this ceruse, besides the rotting of the teeth, and the unsavory breath which it causeth, doth turn fair creatures into infernal Furies.”

That’s just the bit on Venetian ceruse. And while he might be right about the negative health impacts there, he has similar things to say about rouge or blush. Of that idea he says:

“O desperate madness; O hellish invention; O devilish custom, can there be any greater dotage or foolishness in the world?”

(both quotes from Tuke, 14)

Women seem to have found all these complaints eminently ignorable. There was a time when makeup fell out of favor generally, but not yet and not for long. I will be talking about that next week.

Selected Sources

Burke, Jill. How to Be a Renaissance Woman. Profile Books, 3 Aug. 2023.

Eldridge, Lisa. Face Paint : The Story of Makeup. New York, Abrams Image, 2015.

Felici, Elisa. “Traditional Chinese Makeup: Exploring Chinese Beauty.” Www.pandanese.com, 12 Apr. 2023, http://www.pandanese.com/blog/traditional-chinese-makeup.

Green, Monica. The Trotula: a Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine Edited and Translated by Monica Green. 2001.

Hinsch, Bret. Women in Tang China. Lanham, Rowman & Littlefield, 2020.

Li, Shanshan. “Makeup Trends throughout Ancient Chinese History.” Euphoric Sun, Euphoric Sun, 22 Apr. 2022, euphoricsun.com/blogs/asian-inspiration-beauty/makeup-trends-through-ancient-chinese-history#:~:text=During%20the%20Qin%20Dynasty%2C%20%E2%80%9Cred. Accessed 31 Aug. 2024.

Lomazzo, Giovanni. “A Tracte Containing the Artes of Curious Paintinge, Caruinge & Buildinge : Lomazzo, Giovanni Paolo, 1538-1600.” Internet Archive, 2014, archive.org/details/tractecontaining00loma/page/130/mode/2up. Accessed 31 Aug. 2024.

Mansell, Katharine. “Recreating a 2,000-Year-Old Cosmetic.” Nature, 3 Nov. 2004, https://doi.org/10.1038/news041101-8.

McDaniel, Spencer. “The Shocking Truth about Ancient Greek Makeup.” Tales of Times Forgotten, 28 Aug. 2021, talesoftimesforgotten.com/2021/08/28/the-shocking-truth-about-ancient-greek-makeup/.

Ovid. “Ars Amatoria; Or, the Art of Love Literally Translated into English Prose, with Copious Notes.” Gutenberg.org, 2014, http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/47677/pg47677-images.html.

—. “Medicamina Faciei Femineae.” Www.poetryintranslation.com, http://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Latin/TheArtOfBeauty.php.

Palmieri, Anna. Caterina Sforza and Experimenti. Translation into English and Historical-Linguistic Analysis of Some of Her Recipes. https://amslaurea.unibo.it/13749/1/Caterina%20Sforza%20and%20Experimenti.%20Translation%20into%20English%20and%20historical-linguistic%20analysis%20of%20some%20of%20her%20recipes.pdf, 2016.

Patkar, Kunda B.., Bole, P. V.. Herbal Cosmetics in Ancient India: With a Treatise on Planta Cosmetica. India: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 1997.

Plato. “Gorgias, by Plato.” Www.gutenberg.org, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1672/1672-h/1672-h.htm.

Riordan, Teresa. Inventing Beauty : A History of the Innovations That Have Made Us Beautiful. New York Broadway Books, 2004.

Simpson, Cara, and Oginia Tabisz. “Roman Fingerprints Found in 2,000-Year-Old Cream.” The Guardian, 28 July 2003, http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2003/jul/28/artsnews.london.

Stos-Gale, Z. A., and N. H. Gale. “The Sources of Mycenaean Silver and Lead.” Journal of Field Archaeology 9, no. 4 (1982): 467–85. https://doi.org/10.2307/529683.

“The Kama Sutra of Vatsyayana, Trans. By Richard Francis Burton, Bhagavanlal Indrajit, and Shivaram Parashuram Bhide.” Www.gutenberg.org, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/27827/27827-h/27827-h.htm.

Tuke, Thomas. “A Treatise against Paintng and … 1616.” Internet Archive, 2023, archive.org/details/bim_early-english-books-1475-1640_a-treatise-against-paint_tuke-thomas_1616/page/n13/mode/2up. Accessed 31 Aug. 2024.

Tyldesley, Joyce A. Daughters of Isis : Women of Ancient Egypt. London ; New York, Penguin, 1995.

Xenophon. Xenophon in Seven Volumes, 4. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA; William Heinemann, Ltd., London. 1979. https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Xen.%20Ec.%2010&fromdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0212

[…] left off last week with makeup in Renaissance Europe, when women of all classes were smearing their forces with all […]

LikeLike

Is this the edo period?

LikeLike

[…] Throughout history and around the globe, women have routinely squeezed, bound, crushed, tweezed, poisoned, pricked, and stretched various portions of their anatomy, sometimes with permanent ramifications, […]

LikeLike