It is a never-ending struggle on this podcast to include the stories of women who are neither European nor American. (It’s the sources, people, the sources.) I thought, for sure, this episode was the non-Western world’s moment. After all, the very word “tattoo” comes from Captain James Cook’s diaries. On visiting Tahiti in 1769, he wrote “both sexes paint their Bodys, tattow, as it is called in their language. This is done by inlaying the color of black under their skins in such a manner as to be indelible … the women generally have this figure Z simply on joint of their fingers and toes” (Anderson, 1).

That is how the word got into English and why it’s a very strange word phonologically. It’s a borrowed word. Generally speaking, the reason to borrow a word is because you don’t already have one: it’s a new concept for your culture. I knew that so I thought I’d be spending more of this episode on the South Pacific and less on the cultures that I usually cover.

But I was mostly wrong. It turns out that tattooing is thousands of years old, and there are at least as many cultures that have it as ones that don’t. The ones that had it include the standard big ones that we talk about all the time. There are prehistoric mummies that were clearly tattooed, but I’m skipping them and jumping straight to Egypt where the evidence suggests tattooing was far more common for women, than it was for men (Tassie, 88). Which I’m finding interesting because I said just a few weeks ago that both men and women wore cosmetics in Egypt. There are a handful of male mummies with tattoos, but there are a whole lot more female ones (Tassie, 89; Ghosh).

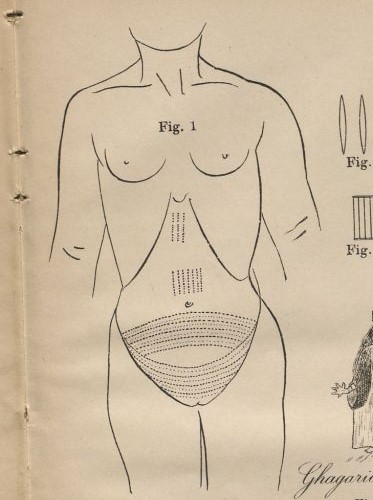

The one I am specifically going to talk about is Amunet, a priestess of Hathor, who lived shortly before 2000 BCE. On her left shoulder and breast is a row of dots inside two lines. She has rows of dots on her right arm. Her abdomen has rows of dashes and dots in three separate groups. Other female mummies found nearby have similar markings. We frequently do not get to know why people in the past did what they did, but Amunet has a title: She is the “King’s Favorite Ornament!” Which might be a clue (Tassie, 90).

Further south in Nubia, women were also getting tattooed, but possibly not for the same reason. Women there got tattoos of Bes, god of childbirth, on their thighs. It was a talisman. Protection (Tassie, 94). Other Nubian mummies show extensive other designs, with possible healing or protective connotations (Austin).

There’s a reason I’m talking about Egypt. It’s because they were the ones who mummified the bodies, left them in a very dry environment, and get a great deal of funding for archaeological digs.

It is not because they were the only ones doing tattoos. On the contrary, tattoos are all over the place. On St Lawrence Island, Alaska, a 1,600-year-old mummified woman was found with tattooed arms. She has alternating rows of dots and solid lines. And—get this—several hearts (Smith). Presumably the heart shape didn’t mean the same thing to her as it does to us. There’s a wikipedia page on that, if you’re interested.

Other mummies with tattoos have been found in China, Russia, Sudan, Mexico, Chile, Peru, and on and on. They are all over the place. (Deter-Wolf).

When we have the actual mummy, that is pretty conclusive evidence. When we only have art, that’s tricky. Is it a tattoo? Or is it body paint? Is it the artist’s imagination? It’s hard to tell, but it’s possible tattoos were even more widespread than what I’ve just mentioned.

If we move into times where written records are more plentiful, the field gets muddier not clearer. For example, Leviticus 19:28 says “Ye shall not… print any marks upon you: I am the Lord”. That’s the King James translation, and of course it doesn’t use the word tattoo because Captain James Cook hadn’t been born yet. But tattoo is probably what it meant, and the reason was probably because the children of Israel had neighbors who did do tattoos. It was foreign. Therefore barbaric, and sacrilegious, etc.

Some of these neighbors were mentioned in Greek sources, too, at about the same time period. The Greeks called these people the Thracians and specifically mentioned that among them “it is an adornment for girls to be marked.” The verb used there is stizethai, a root that later came into English as “to stitch” or “stigma,” which in early days did not mean social disapproval. It meant a pricking (Jones/Kaplan, 3-6). In other words, a tattoo.

Greek authors noted this because they did not use tattooing as adornment. They used it for punishing criminals. At least at first.

Tattoos in Christianity and Islam

Early Christians were on the side of the Thracians. They did do tattoos, an idea that was probably spurred on by St Paul. He says in Galatians 6:17 that he bears the marks of Jesus on his body. Paul probably meant that metaphorically. He was born and raised a Jew after all; he definitely knew his Leviticus.

But when a religious leader speaks in metaphor, it is often only a matter of time before his followers take him literally. Many early Christians got tattoos, often in the shape of the cross or of the nail prints in hands and feet like Jesus. These marks became known as the stigmata. Because stigmata was the Greek word Paul used. Again, it meant to prick (Gustafson/Kaplan, 29). There are some branches of Christianity that still do this, like the north African Copts.

However, the relationship between Christianity and tattooing was not all smooth sailing. At various points, church leaders would say something along the lines of don’t do it because the body is Gods’ creation or they might say do it only if the design is Christian and for heaven’s sake don’t do the pagan designs (University of Oxford). That last comment was made all the way up in the northern part of England in 787 CE, which tells you two things: there were still plenty of pagans in England and people on both sides of the religious divide were interested in tattoos.

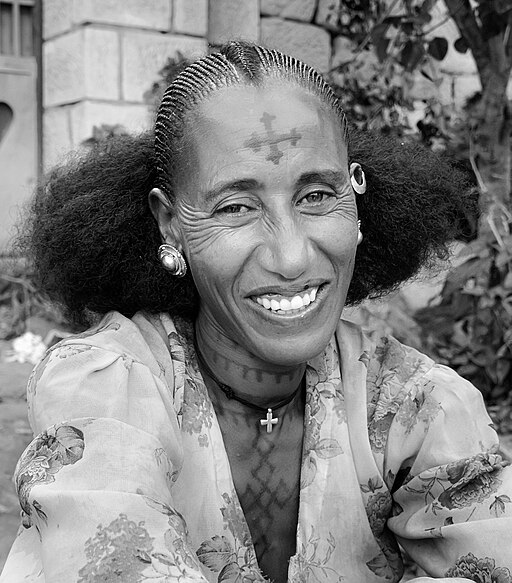

When Islam got going, it would have essentially the same internal debate. Which makes it all the more interesting that there has been widespread tattooing among some Muslim groups. The group I’m going to focus on are the Amizagh of North Africa. You may know them better by the term Berbers, but they prefer the term Amizagh.

The Amizagh have a tradition of facial tattoos, specifically for women. A girl received her first tattoos as a puberty ritual, soon after her first menstrual cycle. Different regional groups had their own designs and styles, but there was also individual expression. Even sisters might have different patterns (Becker, 47-49). That much information is from fairly recent anthropology studies about a custom that is dying. But we know the custom is centuries old at least. And one reason we know it is that we can see evidence of it from an unexpected direction.

In the year 1545, the Italian artist Paris Bordon painted a canvas called Venetian Women at their Toilet. Toilet, by the way, is still a generic term for your morning routine: washing, dressing, hair, makeup, etc.

The two Venetian beauties in this painting are blond, buxom, and … boring. Basically the Renaissance version of Barbie. Overly idealized, they look more like toys than like living, breathing women who might someday have a pimple or a wrinkle. But the third woman in the picture is different. She’s hovering behind, looking like her job is to be helpful. She might be a slave (Burke, 87-88) or she might be a procuress (Humfrey) getting the girls ready for a night of hard work, if you know what I mean. But either way she is different. She has much darker skin, and she wears a head covering. If you zoom in on her face, you can see facial tattoos.

As far as I can tell, Bordon left no written explanation of this painting or who the models were. Which is a crying shame. But failing that we can only deduce: This woman was probably Amazigh, from North Africa, a place well within reach of Venice’s merchant ships. She lived in her own culture long enough to receive the tattoos marking her as a woman, not a girl. Some time after that, she left her people, and possibly that was not of her own free choice. Eventually she ended up working in Venice, still possibly not of her own free choice.

She is precisely the type of woman that historians say little about because most women with her life story are entirely lost in the past, leaving no hint that they ever existed at all.

Tattoos in the Colonies

Over in India, some Hindu women got tattoos over the spleen and liver to prevent having a still-birth. There were other medicinal uses too, Also the bindi (that dot that they sometimes wear on the forehead) was sometimes tattooed on, where it symbolized chastity and fidelity. They varied by caste so much that European observers used them as caste markers (Anderson, Caplan, 104).

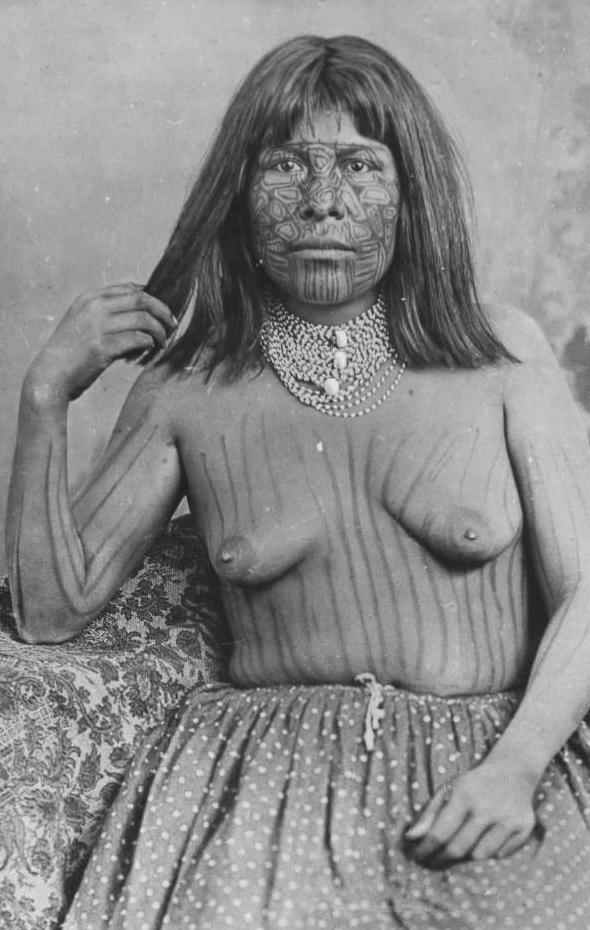

Clear on the other side of the world, English writers who did not yet have the word tattoo made do with other verbs to describe the Native American women they encountered. For example, in 1614 Samuel Purchas wrote that among the Algonquian Indians, “the women… pounce and raze their bodies, legs, thighs, and arms in curious knots and portraitures of fowls, fishes, beasts, and rub a painting into the same, which will never out” (Purchas, 768).

John White was the artist sent to Roanoke, and he painted local Indian women with tattoos.

(Wikimedia Commons)

You may have noticed that we have reached the age of exploration and conquest, and Europeans were sufficiently aware of the rest of the world to know about tattooing even if they weren’t doing it much themselves. Any person of European descent who had a tattoo was likely to be a man and a sailor. That was certainly the stereotype of a tattooed European: sailors who picked up bad habits in those dirty, foreign places.

But that stereotype was about to change, and not necessarily for the better. The woman who led the change certainly never planned on doing so.

White Women and Tattoos

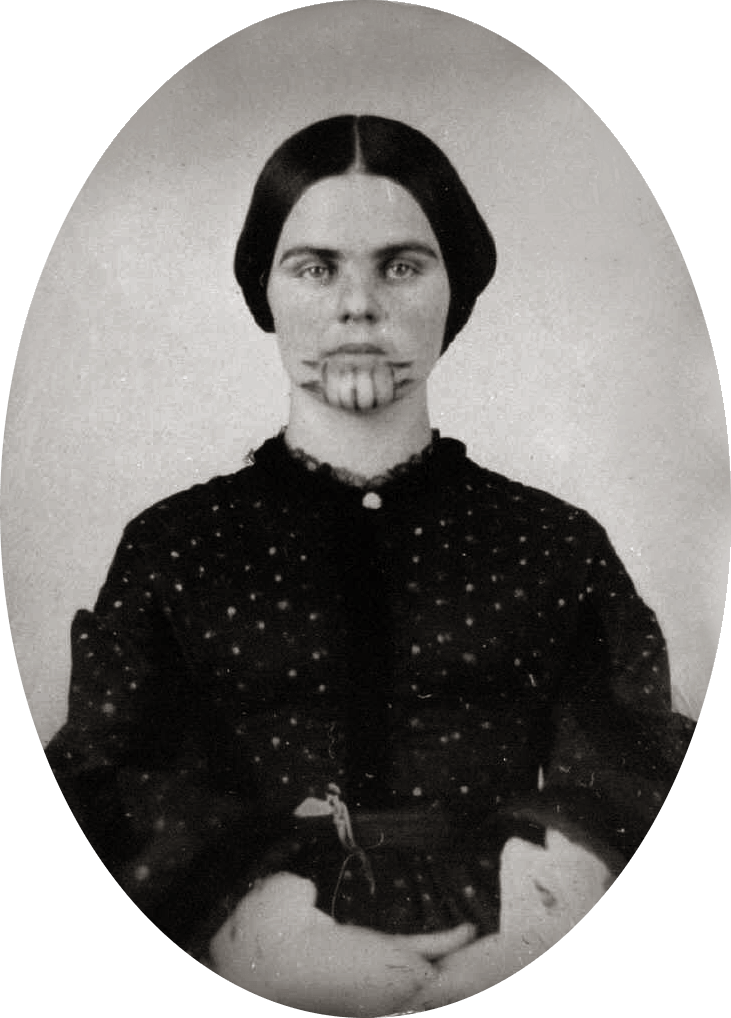

In 1851, the Oatman family decided to move from their home in Illinois to southern California. But in the Arizona desert, they were attacked by Yavapai Native Americans who killed both parents and four of the seven children. Fifteen-year-old Lorenzo was left for dead, though he actually survived and made it to safety. Fourteen-year-old Olive and seven-year-old Mary Ann were taken into captivity. After about a year, the girls were traded to the Mohave tribe.

Mary Ann died, but Olive lived with the Mohaves for four years—long enough for authorities at the nearest US military fort to get wind that the Mohaves had a white woman. The news did not go over too well with the American public.

After some tense negotiations punctuated with threats, Olive was handed over. She was later reunited with her brother Lorenzo, and in 1857 a book was published about her experience. It was a bestseller, and both siblings lived on the royalties and speaking engagements.

The reason any of this is relevant to today’s episode is that Olive now had a very striking appearance. You’ll see there that she has five tattooed stripes on her chin and two horizontal stripes coming out each side.

Olive said that the tattoos were to mark her as a slave, which fit right in with what white Americans wanted to believe about Native Americans (Stratton).

What Olive didn’t say was that Mohave woman frequently had such tattoos. It didn’t mean slavery; it meant acceptance into the tribe and preparation for a good afterlife.

Olive’s Yavapai experience was certainly a traumatic abduction. Her Mohave experience may have been more like an adoption. Experts have even suggested that if Olive had actively struggled during the procedure or the aftercare, her lines wouldn’t be as straight and clean as they are. The tattoo itself suggests she was a willing participant (Mifflin, 16-21).

My response to that is that lack of active struggle does not equate to consent. There are all kinds of ways to put on the pressure, and not all of them are physical. But it is true that Olive spoke very positively of many of the Mohaves and claimed that they did not mistreat her. The experience was not all bad.

However, the sensational version of the story sold better, a fact which other white women did not fail to notice. By the1880s, you only had to visit a circus to see a tattooed lady. Tattooed men, too, but ladies were a much bigger crowd pleaser. Many of these women told some fabulous tale of a harrowing ordeal among savages (usually Native American, but sometimes south Pacific). Most of these stories were demonstrably untrue (Mifflin 16-21).

Olive’s story was more-or-less real, and perhaps a few others were too, but for the most part, these were women who got tattooed on purpose because they needed a job. They may have preferred this to the limited other options.

Women who did not need a job began to take note as well. There were unsubstantiated rumors that many society ladies had discreet tattoos in private places even during Victorian times (Mifflin, 43). Much of that was probably still just sensationalism, but maybe not all.

In the 20ᵗʰ century, movies put freak shows out of business. Being a tattooed lady was no longer financially viable. Tattoos decreased in popularity for a while. Especially after World War II, when tattooing was linked to both Nazi concentration camps and a few heavily publicized cases of hepatitis from unclean tattoo needles (Mifflin 25-26). For a while there, tattooing was a very, very low class thing to do.

I suspect you have noticed that is no longer the case. Tattooing has been rising popularity for decades now. To the extent that last time I visited a public pool, it appeared to me that I am the only woman over 18 who still doesn’t have one. That’s probably not true, but if you do have one, you are part of a very long-standing worldwide tradition.

Henna

I think of henna as coming from India, but that is not the original version. The plant henna comes from the Mediterranean world, and there is plenty of evidence that it was known and used as a hair dye and perfume in Egypt, Greece, Rome, ancient Israel, and many neighboring cultures (Sienna, “Period Henna”). But as far as I can tell, there is no evidence it was used for beautiful designs on the skin at that period.

By the medieval period, henna had spread in multiple directions. Muslim control stretched across north Africa and up into the Iberian peninsula, an area called al-Andalus. They definitely used henna on the skin, but not always in patterns. More often a woman’s fingers were dipped into the henna, so they were solidly red or brown with maybe a little dotting or scrollwork at the edges.

Andalusian poetry confirms this, including one with grisly reference to a femme fatale, her fingers red with the blood of slain lovers. It’s actually henna, but apparently the poet was a little imaginative.

And desperate.

As an interesting sidenote, this particular poet was Jewish, living what appears to be a very successful life in a Muslim-controlled state. It was a multi-cultural world (Sienna, “Her Fingers Stained”).

Anyway, henna in al-Andalus continued all the way until Queen Isabella kicked the Moors out of Spain and the Inquisition banned henna as something only an infidel would do (Sienna, “Period Henna”). Presumably it remained alive and well in north Africa, though as you know from earlier in this episode, they did tattooing there as well.

In the opposite direction, henna was also enthusiastically embraced in Persia, the empire that was roughly where the modern country of Iran sits. They had the dipped finger style too, but they also did designs on the hands and the arms. Artwork depicting this starts in the 1100s and continues for hundreds of years (Sienna, “Period Henna”; Cartwright-Jones, 78).

Persian poetry confirms this with plenty of lines like “dyed with henna, as is a bride’s hand” or “O, wipe the woman’s henna from thy hand” (Cartwright-Jones, 10).

Persian women were doing the beautiful designs we now associate with henna: trees, birds, stars, flowers. According to one written account, this was done all over the body, but Persian women are painted with their clothes on, so we don’t have any visual of that (Cartwright-Jones, 13). We do see it on hands and arms. However, it was definitely a special-occasion only event. One survey studied a large swath of Persian art and found that only about 5% of the women depicted showed evidence of henna designs. But I will say, it’s unmistakable in many of those.

As for India, henna got there much later than I would have expected. They only seem to have picked it up in the 1600s, and it was brought by the Persians, who helped establish the Mughal dynasty. The Taj Mahal is a Mughal creation, built for the empress Mumtaz Mahal. The painting scholars are pretty sure is of her, shows her with hennaed fingertips. It’s a solid dipped color, not a patterned design.

Apparently it’s not until the mid- 20ᵗʰ century that we have solid evidence of the beautiful mehndi designs now so associated with India (Sienna, “No Paisley”). This is considerably later than I expected. So much so, that I can’t help thinking I’m missing a source. If you know what it is, please send me a note.

If I had had to guess, I’d have said henna was older than tattooing, since it seems technologically easier, not to mention less painful. On the other hand, there may have been any number of women and cultures who used henna without leaving us any record.

Selected Sources

Anderson, Clare, et al. Written on the Body : The Tattoo in European and American History. Edited by Jane Caplan, Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 2022.

Austin, Anne, and Cédric Gobeil. “Embodying the Divine: A Tattooed Female Mummy from Deir El-Medina.” Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, no. 116, 1 Sept. 2017, pp. 23–46, https://doi.org/10.4000/bifao.296.

Becker, Cynthia. “Amazigh Textiles and Dress in Morocco Metaphors of Motherhood.” African Arts 39, no. 3 (2006): 42–96. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20447780.

Burke, Jill. How to Be a Renaissance Woman. Profile Books, 3 Aug. 2023.

Cartwright-Jones, Catherine. The Patterns of Persian Henna (PhD Dissertation). Kent State Univerisity, Geography Department, 2009.

Deter-Wolf, Aaron, et al. “The World’s Oldest Tattoos.” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, vol. 5, Feb. 2016, pp. 19–24, reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S2352409X15301772?token=E7172A0F857DB8AE390B9716FE94CE07A2AF2A546D5E3C059B9AF39820E3230D021B6BEF2FCD5EA7F68F445116CABE5B, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2015.11.007.

Ghosh, Pallab. ““Oldest Tattoo” Found on 5,000-Year-Old Egyptian Mummies.” BBC News, 1 Mar. 2018, http://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-43230202.

Humfrey, Peter. “Venetian Women at Their Toilet.” National Galleries of Scotland, 2016, http://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/4688.

McCabe, Carolina. “The Disappearing Tradition of Amazigh Facial and Body Tattoos.” Https://Www.moroccoworldnews.com/, 7 Apr. 2019, http://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2019/04/269903/tradition-amazigh-facial-tattoos.

Mifflin, Margot. Bodies of Subversion : A Secret History of Women and Tattoo. New York, Juno Books, 2001.

Purchas, Samuel. Purchas His Pilgrimage. Or Relations of the World and the Religions Observed in All Ages and Places Discovered, from the Creation Vnto This Present. Contayning a Theologicall and Geographicall Historie of Asia, Africa, and America, with the Ilands Adiacent. Declaring the Ancient Religions before the Floud, the Heathenis, Iewish, and Saracenicall in All Ages Since. London, Printed By William Stansby For Henrie Fetherstone, 1626, archive.org/details/purchashispilgri00purc/page/768/mode/2up?q=knots. Accessed 12 Sept. 2024.

Sienna, Noam. ““Her Fingers Stained Red from the Blood of the Slain”: Henna in Medieval Hebrew Love Poetry.” Blogspot.com, 2014, eshkolhakofer.blogspot.com/2013/07/today-on-jewish-calendar-is-15th-of.html. Accessed 22 Sept. 2024.

—. “Eshkol HaKofer: The First Indian Mehndi Design? Rare Henna in a Mughal Painting.” Eshkol HaKofer, 10 May 2015, eshkolhakofer.blogspot.com/2015/05/the-first-indian-mehndi-design-rare.html.

—. “No Paisleys? A History of Indian Henna Designs.” Blogspot.com, 2014, eshkolhakofer.blogspot.com/2014/11/no-paisleys-history-of-indian-henna.html.

—. “Period Henna: A Resource Guide for Henna in the SCA.” Blogspot.com, 2015, eshkolhakofer.blogspot.com/2015/01/period-henna-resource-guide-for-henna.html. Accessed 22 Sept. 2024.

Smith, George S., and Michael R. Zimmerman. “Tattooing Found on a 1600 Year Old Frozen, Mummified Body from St. Lawrence Island, Alaska.” American Antiquity 40, no. 4 (1975): 433–37. https://doi.org/10.2307/279329.

Stratton, Royal. “Captivity of the Oatman Girls, by R. B. Stratton—a Project Gutenberg EBook.” Www.gutenberg.org, 1858, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/55071/55071-h/55071-h.htm.

Tassie, G., (2003) “Identifying the Practice of Tattooing in Ancient Egypt and Nubia”, Papers from the Institute of Archaeology 14, 85-101. doi: https://doi.org/10.5334/pia.200

University of Oxford. “Pitt Rivers Museum Body Arts | Wooden Tattooing Stamp.” Web.prm.ox.ac.uk, web.prm.ox.ac.uk/bodyarts/index.php/permanent-body-arts/tattooing/170-wooden-tattooing-stamp.html.

[…] history and around the globe, women have routinely squeezed, bound, crushed, tweezed, poisoned, pricked, and stretched various portions of their anatomy, sometimes with permanent ramifications, sometimes […]

LikeLike