Most of the episodes in this series have been on what women did to make themselves beautiful, whatever that happened to mean at the time. But this episode is doing double duty as my second annual Halloween episode and it is about what calamity might happen if—perchance—your body happened to have a blemish.

It was the year of our Lord, 1712, in the county of Hertfordshire, England. The Reverend Godfrey Gardiner and his wife Deborah had just welcomed a young guest to the home: Francis Bragge, a local deacon.

The Reverend had been in the parlor chatting with his guest for only a few minutes when the shrieking began.

Running to the source of the noise, they saw Anne Thorne, the 16-year-old servant girl in nothing but her underdress, crying “I am ruined and undone!”

Her overdress was in a bundle on the floor, with twigs and dead leaves wrapped up in it. She explained that she had “a strange roaming in her head” and knew she must run from the house. An old woman had told her to gather sticks in her dress. And then the old woman vanished.

She had done as instructed and ran back home before falling into hysterics. Though the total distance was a mile, Anne had been so fast she was gone only six or seven minutes, and this though her knee had been injured only the day before.

Horrified, Mrs. Gardiner threw the sticks onto the fire. And as they did so Jane Wenham appeared at the door. Jane was much older than Anne, about seventy, and already disliked in the village.

Her neighbor John Chapman was sure she had cursed his horses and cattle to a loss of 200 pounds. He had said she was a witch, and she had taken him to court on a charge of slander. The magistrate did not give her satisfaction, as she had a bad reputation, but he did refer her to the Minister, Reverend Gardiner, who did allow that Chapman ought to pay her a shilling in damages, but also advised her to live more peaceably with her neighbors. At that she was very angry and was heard to say that if she could not have justice here, she would have it elsewhere.

“Revenge,” says the pamphlet that was soon to be published recounting the events, “is naturally the first new thought that is excited by anger in a wicked mind” (Bragge, 3).

So was it any surprise that some bewitchment should befall a member of Reverend Gardiner’s household? Surely, it was not.

Nevertheless, the Reverend was cautious. He looked for witnesses of Anne’s unbelievably speedy flight and indeed two men said they had seen her running so quickly they could not stop her.

The next day Anne was apparently much recovered because she was sent to the neighbor’s on an errand. But she met Jane in the road on the way. Jane demanded to know why Anne was telling stories on her and said “if you tell any more such stories of me, it shall be worse for you than it has yet been” (Bragge, 5).

The compulsion to fetch more sticks came over her several more times, and sometimes she was speechless and at other times she shrieked and struggled against all restraint. Once she attempted to throw herself into the river and at other times she leaped over fences and gates as if she were a greyhound (Bragge, 26). Frequently she pointed to Jane Wenham’s house as if that were the source of the trouble.

By now there was a warrant for Jane’s arrest, but she refused to come out of her house. The constable shouted at her to open the door and she shouted back that she knew what to do better than him. So he broke it down.

They dragged Jane to see Anne, who was lying, speechless until Jane came near, when she started up and cried “You are a base woman, you have ruined me … I must have your blood or I shall never be well!” And she dragged her nails against Jane’s forehead.

But no blood came!

Though her forehead was badly mangled, Jane held quite still and said “Scratch harder Nan, and fetch blood of me if you can!” (Bragge, 10).

The assembled crowd was now quite sure Jane was a witch and probably had been for twenty years at least. For her part Jane said she was innocent, and she was willing to prove it, either by a search of her body for the witch’s mark or trial by water.

What Was the Witch’s Mark?

I will now pause the story to explain what Jane did not have to explain to her audience—the witch’s mark.

There are actually two terms, witch’s mark and devil’s mark and they are sometimes used interchangeably and at other times not, just to be confusing.

The Devil’s Mark is the older concept, and it was given by the Devil to a witch to seal her (or his) obedience and service at the end of a nocturnal initiation. This made perfect sense to many people. For example, in 1705, one author wrote that “‘Tis but rational to think that the devil, aping God, should imprint a sacrament of his covenant” (J. Bell, quoted in McDonald, 507). I am actually not sure at all why that is rational, since Christian baptism does not leave a permanent physical mark (I can attest this from personal experience). Communion or the Eucharist leaves you similarly unscarred.

Yet the Devil’s Mark was a belief held widely across Europe. It might be anywhere on a witch’s body and conveniently for an accuser, it might look like practically anything, being variously described as:

- a little blue spot

- a little red spot

- a little sunken flesh

- a flea bite

- a small mole

- a protuberance

- a hard, horny bit of skin

- an impression of a rabbit foot, a rat’s foot, or a spider (McDonald, 507).

As you can imagine, a lot of people had some part of their body that matched one or more of those descriptions.

So it is fortunate for the accused that there was a further test. This devil’s mark was supposed to be insensitive to pain and would not bleed when pricked. As a result it was possible—and I am not kidding here—to become a professional witch-pricker. You’d travel around and when some poor woman (or occasionally a man) was accused of being a witch, you’d whip out a pin and stab the person in a likely spot to see if they react and if they bleed. John Bell (the one who wrote that it was so rational for the Devil to mark his own) was a witch-pricker. Even at the time, there were many people who knew full well that this profession was ethically dubious, if not a downright cheat (McDonald, 509; Mackenzie, 92).

You may notice that Jane Wenham did not bleed when scratched with Anne Thorne’s nails, which is interesting, because this idea was not what she meant when she offered to be searched for a witch’s mark.

The Devil’s mark sealing you as his servant was a common concept in Scotland and continental Europe, but Jane was in England, where the more common test was for a witch’s mark, a far more specific concept (Miller, 59).

The witches’ mark was an extra nipple or teat. This nipple was used to suckle your familiar (a cat or spirit that drank your blood and did your bidding).

Though we often think of witches in the Middle Ages, most of our stereotypical ideas about witches actually come from the early modern period. It was in the late 1570s that the idea of a familiar who sucked your blood started to surface, and in the 1580s that we first see the idea that it would leave a permanent mark. By 1600 English demonologists (yes, that’s a profession too) were touting it as a possible proof of guilt to be used in court. And it had been used in court. In 1621 Elizabeth Sawyer had been convicted and executed after a witch’s mark was found near her anus. In 1645, witch’s marks had been found on a whole host of witches executed together (Hutton, 275). By the time of Anne Thorne accused Jane Wenham in 1712, the concept was very well known.

And Jane Wenham had a familiar. The townspeople knew because at the time Anne Thorn met Jane in the road and was threatened by her, Jane was actually three miles away and she had a witness to prove it. So obviously it was her familiar taking her shape who had threatened Anne. Clearly. Obviously.

And if she had a familiar, then the familiar had to be surviving on Jane’s blood. Obviously again. And therefore, there should be a mark on her body. A rational mind might think of other possibilities, but just hold that thought. I will now return to the story.

Back to the Story

Sir Henry Chauncy, the local legal authority, ordered four women to search Jane thoroughly for any teats or “other extraordinary or unusual marks about her, by which the Devil in any shape might suck her body” (Bragge, 11).

The search took an hour, and the four women reported that they found nothing.

But that was hardly conclusive. A 1646 pamphlet had suggested a witch could cut off her teats before capture and thus avoid detection (Millar, 160; Thomas, 551).

Anne Thorne was still collapsing in fits and people all over the village were being tormented by cats who had the face of Jane Wenham.

Then to the astonishment of everyone, it was found that Jane Wenham could not recite the Lord’s Prayer! Not by memory and not even when it was given to her sentence by sentence. She repeatedly stumbled over the part that says “lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil! When Jane repeated that it came out as “lead us not into no temptation and evil” or “lead us into temptation and evil” very suggestive stumbles, to be sure, and the growing suspicion was not allayed when she said she was much disturbed in her head and that was why she couldn’t get it right.

Over the next several days, several witnesses came forward to say that Jane was definitely a witch because they had had a child or a cow die after a run-in with Jane.

And there was more, for while Sir Chauncy questioned Jane, a pin came into her fingers. She had plucked it out of nowhere.

Sir Chauncy snatched the from her fingers and stabbed her in the arm with it six or seven times and there was no blood. Nor did Jane so much as wince. Indeed, she was led away for the night and she spent it singing and dancing.

The following day Jane confessed to being a servant of the devil these sixteen years and was sent to jail to await formal trial. At the trial sixteen witnesses appeared to testify against her, and when Anne Thorn was brought to the witness stand, she had a fit right there in the courtroom.

The jury found Jane guilty.

A Post-Trial Evaluation

It is easy for the modern mind to feel very superior to the credulous fools of the past, but that is misplaced for several reasons. One because we undoubtedly have our own set of mistaken beliefs, and two because even in the past, public opinion was divided. Far from a universal hysteria, there were many who were pleading for a little calm and rational thought. Not to mention compassion.

The judge was clearly one of these. When the jury said Jane was guilty, he sentenced her to death as the law required, but immediately reprieved her until further orders.

And such further orders did not come. It is even said that he appealed to Queen Anne on her behalf.

The judge was undoubtedly an educated man, so perhaps he had read any of a number of written pleas to stop this witch-hunt stuff. For example, he may have read a book by Scotsman George Mackenzie, written in 1678, which sounds very modern in its thought-process. Mackenzie says:

Those poor persons who are ordinarily accused of [witchcraft], are poor ignorant creatures, and oft-times Women who understand not the nature of what they are accused of; and many mistake their own fears and apprehensions for Witch-craft; of which I shall give you two instances, one of a poor Weaver, who after he had confess’d Witch-craft, being asked how he saw the Devil, he answered, “like flies dancing about the candle.” Another of a woman, who asked seriously, when she was accused, if a woman might be a witch and not know it? And it is dangerous that these who are of all others the most simple, should be tryed for a Crime, which of all others is most mysterious.

These poor creatures when they are defamed, become so confounded with fear, and the closse Prison in which they are kept, and so starved for want of meat and sleep, (either of which wants is enough to disorder the strongest reason) that hardly wiser and more serious people then they would escape distraction: And when men are confounded with fear and apprehension, they will imagine things very ridiculous and asurd, and as no man would escape a profound melancholy upon such an occasion, and amidst such usages; therefore I remit to Physicians and others to consider what may be the effects of melancholy, which hath oft made men, who appeared other wayes solid enough, imagine they were Horses, or had lost their Noses, &c. And since it may make men erre in things which are oblivious to their senses, what may be expected as to things which transcends the wisest mens reason.

…

I went when I was a Justice-Depute to examine some Women, who had confest judicially, and one of them, who was a silly creature, told me under secresie, that she had not confest because she was guilty, but being a poor creature, who wrought for her meat, and being defam’d for a Witch she knew she would starve, for no person thereafter would either give her meat or lodging, and that all men would beat her, and hound Dogs at her, and that therefore she desired to be out of the World; whereupon she wept most bitterly, and upon her knees call’d God to witness to what she said. Another told me that she was afraid the Devil would challenge a right to her, after she was said to be his servant, and would haunt her, as the Minister said when he was desiring her to confess; and therefore she desired to die.

There is sadly, no knowing what Jane believed when she confessed. Whether it was a deliberate attempt at suicide, or if she was confused and had begun to believe what was said of her? Or even what her own beliefs about witchcraft were, quite apart from whether she believed she herself was one.

She probably was not educated and had not read Mackenzie, but it would also be inaccurate to say that this divide between belief and skepticism was purely on an educational divide. The Reverend Gardiner, Sir Henry Chauncy, and even the guest, Francis Bragge, were all educated men, at least to some extent. Francis Bragge was entirely convinced. It was he who authored the pamphlet from which I have taken all the details.

Meanwhile, you may not have noticed that there are at least four other people who appear to have been on Jane’s side. By which I mean the four unnamed women who examined her body for the witch’s mark or any mark. I don’t know for sure that they were uneducated, but I think it’s very unlikely that they had read any treatises on criminal law, if they could read at all. Nevertheless, they returned to say they couldn’t find anything.

Really?

Jane was 70, poor, and without the benefit of an enormous pharmaceutical and cosmetics industry. I am none of those things, and yet I have several scars, several moles, several calluses, a handful of mosquito bites, and even a small bald spot. Other women had burned for less. I just can’t imagine that four women who wanted to find something wrong with Jane’s body could not have found something to complain about.

Besides all those fairly obvious and innocuous candidates for a witch’s mark, other researchers have suggested others that may have been true for some witches, but evidently not Jane. Their suggestions are supernumerary nipples (which exist for about 1% of the population), tick bites with Lyme’s disease (which do have a distinctive look), scurvy marks, and any number of other skin lesions (Hutchinson, 177). There is even a theory that some of them were tattoos.

The list of possibilities goes on. The fact that these women found nothing suggests they were either scrupulously careful and honest in the despite of prevailing public opinion. Or they were on Jane’s side all along and public opinion was nowhere near as overwhelming as Bragge’s pamphlet leads us to believe.

If Jane was not guilty as charged, then there are a number of other possibilities as to what was going on. One, of course, was that Anne Thorn made the whole thing up. Or that she was genuinely hallucinating. But another possibility is that she really was a victim, and of a far more common crime. After all, if you were to come upon a young, beautiful, crying teenage girl in state of disheveled undress, is witchcraft the first crime that would come to your mind? I would be thinking more along the lines of rape.

If so, she was genuinely coping with the immediate aftermath trauma. Then her employers came into the room, and she may very well not have felt comfortable telling them the truth. She prevaricates a little bit about what really happened outside, and Mrs. Gardiner says the word witchcraft. Jane Wenham, a woman already suspected of witchcraft, shows up at the door at exactly the wrong moment. Nothing would be easier than to deflect a truth that Anne may well have felt ashamed of into a story that was suggested to her by the circumstances. It may even be that she convinced herself. Rape victims often believe they were somehow to blame. Often they believe they will get no justice. (And sadly often, they are right.) But if she was bewitched the whole time? It was not her fault. And justice was possible.

All of this is just speculation, of course. I have no proof at all that that is what happened. But it would also explain why two young men were so eager to witness her original speedy flight. They were obviously on hand in the area. And if they were the real guilty parties, then they were also more than happy to deflect the blame. They may even have believed they were bewitched themselves. That way they could tell themselves that they too were innocent.

After that, it was collective fear and dislike of a woman who was old and cranky and easy to blame for anything that went wrong. You can imagine many fearful things when you are already primed to be afraid.

Regardless of the truth, Jane was very fortunate to be living when she did. The witch craze of the 17th century was already dying down. Her trial is sometimes called the last witch trial in England, which I think is not quite true, but close. With the help of her judge and others of like mind, she was given a place to live in a neighboring county, where she lived for another twenty years. One of these authors arguing against the witchcraft craze sought her out to hear her story and reported that he had a perfectly cordial visit with her, but she insisted on reciting the Lord’s Prayer for him. When not rattled and in fear of her life, she was perfectly capable of doing so (Hutchinson, 165).

Selected Sources

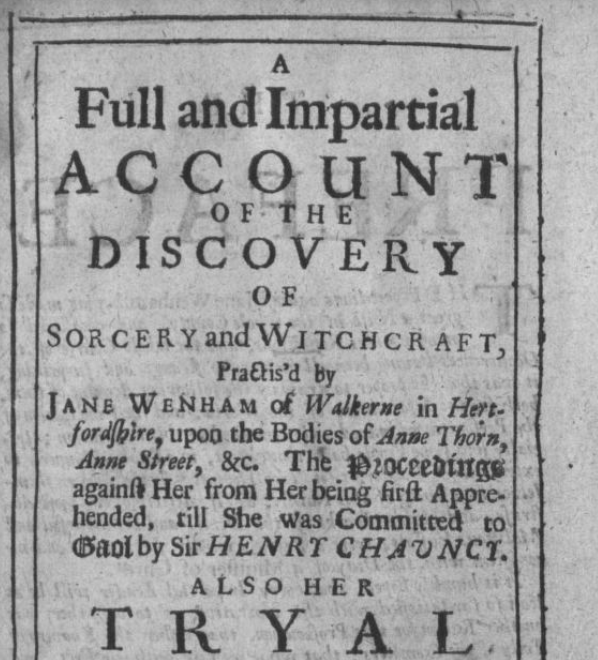

Bragge, Francis. “A Full and Impartial Account of the Discovery of Sorcery and Witchcraft, Practis’d by Jane Wenham… : London: Printed for E. Curll, 1712.” Internet Archive, 2015, archive.org/details/AFullAndImpartialAccountOfTheDiscoveryOfSorceryAndWitchcraft. Accessed 24 Sept. 2024.

Guskin, Phyllis J. “The Context of Witchcraft: The Case of Jane Wenham (1712).” Eighteenth-Century Studies 15, no. 1 (1981): 48–71. https://doi.org/10.2307/2738402.

Hutchinson, Francis. An Historical Essay Concerning Witchcraft with Observations upon Matters of Fact; … And Also Two Sermons: … By Francis Hutchinson, … London, Printed For R. Knaplock, And D. Midwinter, 1720, digital.library.cornell.edu/catalog/witchcraft057. Accessed 24 Sept. 2024.

Mackenzie, George. The Laws and Customes of Scotland, in Matters Criminal. Edinburgh, James Glen, 1678, quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A50574.0001.001/1:7.4?rgn=div2;view=toc. Accessed 25 Sept. 2024.

Mcdonald, S W. “The Devil’s Mark and the Witch-Prickers of Scotland.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, vol. 90, no. 9, Sept. 1997, pp. 507–511, https://doi.org/10.1177/014107689709000914. Accessed 17 Apr. 2020.

Millar, Charlotte-Rose. Witchcraft, the Devil, and Emotions in Early Modern England. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2017.

Ryan, W. F. “The Witchcraft Hysteria in Early Modern Europe: Was Russia an Exception?” The Slavonic and East European Review 76, no. 1 (1998): 49–84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4212558. Thomas, Keith. Religion and the Decline of Magic : Studies in Popular Beliefs in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century England. London, Folio Society, 2012.

Music for this episode is the “Dream of a Witch’s Sabbath” by Hector Berlioz (Symphonie Fantastique, Mvmt 5). The recording is in the public domain and available on the Internet Archive.

Sound effects for this episode are freely available on freesound.org and include work by Dvideoguy, SoundFlakes, visionear, lotteria001, and others.

I’m still here. I still love your podcast. I saw a very quality production of Witches of Eastwick the Musical on Halloween night, and as far as I can tell, the witches were not tried and were not accused by anyone of being witches.

LikeLike

Thank you so much! I have never seen Witches of Eastwick, but now I need to see if I can track down a performance!

LikeLike