Imagine if a time machine brought visitors from the year 3,000 to your doorstep. You will find much that is strange and wonderful about them. But you can rest assured that something about you will also seem strange to them. Maybe your clothes? Your hairstyle? Your makeup or lack thereof? Any piercings? Tattoos?

I’m assuming the basic body shape won’t change much, but with genetic engineering, you never know, and for sure they may have better methods for ridding themselves of any defects than we currently do. I’m leaving the word “defects” carefully undefined because that is in the eye of the beholder.

Today’s episode is a roundup of things women in the past have done to make themselves beautiful. You might have a different definition of beautiful and that’s okay. No doubt the feeling would be mutual.

Teeth Blackening

My modern culture says my teeth should be white and gleaming, but many historical women were going for the exact opposite effect. Tooth blackening is highly associated with Japan but was actually done for hundreds of years across much of Asia.

There are several ways to make your teeth black. One way is to use iron filings in water with tea powder. The solution becomes non-water soluble, so you can paint it on your teeth, and it will stay for a day or so (Eldridge, 75). This was the most common method in Japan, and we have written records of it dating from the 11ᵗʰ century in the Tale of Genji. The author Murasaki Shikibu (episode 6.2) probably blackened her teeth. Her characters definitely did.

In the following century, there is another Japanese story called The Lady Who Loved Insects. It’s a tale about an unconventional woman who baffled her parents and repulsed her neighbors by doing crazy things … like collecting butterflies and studying their life cycles. She also refused to blacken her teeth because “she thought it was bothersome and dirty. And she doted on the vermin [meaning the butterflies] from morning till night, all the while showing the gleaming white of her teeth in a smile” (Backus, 55).

That last bit is not a compliment.

In fact, people fled from her smile, it was so peculiar. One of her attendants went so far as to say her teeth looked like peeled caterpillars. Ugh! (Backus, 57; Morris, 204)

It is hard to say just how widespread teeth blackening was. Maybe the lower classes didn’t do it. But there are plenty of paintings of upper-class women applying the tooth blackening. There are also a few references to men doing it. But mostly women, and it remained popular in Japan up through the late 19ᵗʰ century when the Meiji emperor forbade it for men, as part of Japan’s race to become more Western than the Westerners (Chamberlain, 57). Women were less regimented. They were the bastions of traditional culture. But there is no doubt that they were stung by Western comments on this practice, which were not flattering, to say the least.

Here’s what was printed in one western magazine in 1868. The author is describing Japanese women he has seen:

“the mouth opens for a smile, a yawning black chasm is seen, made uglier by the deep red colour of the painted lips. These great disfigurements have, however, a meaning, and are the tokens of matrimony. Every married woman, instead of wearing a golden circlet on her finger, makes herself hideous as a matter of course; it is, perhaps, to prove that she loves but one, in whose eyes she ought to be beautiful under any circumstances. Her blackened teeth and face, rendered meaningless by the absence of eyebrows, are a passport to her every-where, and she is permitted the utmost freedom of action. Until they undergo this voluntary disfigurement, Japanese women are, as a rule, very pretty, and even this alteration does not altogether destroy the charm of their appearance and manner. The teeth are blackened by a mixture of steel filings; every day they are cleaned with a powerful tooth-powder, and the mixture re-applied. Custom has wonderful influence; but we think that young English ladies would ponder a long time before uttering the “Yes” which must be followed by such a transformation.”

(“Life in Japan”, 262-263)

I think we can set aside the smug superiority, especially from a culture that was at the time squeezing its women into corsets and hoop skirts. Deliberately making themselves ugly was never the reason for tooth blackening. It’s just that beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

Nevertheless, the practice did die out in Japan, especially after Empress Haruko gave it up (Chamberlain, 57). In other parts of Asia, the custom survived much longer, which is why the available photos of women with blackened teeth are not Japanese. Vietnamese, Thai, Burmese, and others are available, but not Japanese.

A lot of women did this. It was beautiful! The pearly whites my dentist sells? Not so much.

Cranial Modification

Even more widespread than teeth blackening is the practice of artificial cranial modification. It turns out there is no particular reason why your head needs to be shaped the way it is. If your parents thought it should be flatter, longer, or whatever, this is all possible as long as they started binding your head young. Infants have pretty malleable skulls. They don’t harden until age 2 or 3, so until then you can adjust the shape.

This beauty practice has been documented on all continents. Or so says my source. I’m pretty sure Antarctica would be an exception (Tiesler, Bioarchaeology, 1-4).

Back in episode 13.6 on hair, I mentioned that some depictions of Egyptian princesses have them completely bald. But they are not just bald. They have very elongated heads. They look a bit like eggs actually. It doesn’t help with debunking the Egyptian pyramids were built by aliens theory because, in fact, these princesses do look somewhat alien.

Assuming we rule out the aliens theory (which I do), there are other explanations. One of them is hydrocephalus, otherwise known as water on the brain, which can cause the head to be larger than expected. Another possibility is deliberate cranial modification. My major source on the Egyptian princesses actually favors the artistic license theory and maybe these princesses had totally normal heads, but the artist decided to add a few pounds to the head, much in the same way that later artists would shave a few pounds off the waist for a flattering portrayal (Arnold, 55). So I’m really not sure how much this was done in Egypt.

The earliest written source I’m aware of is from the Greek Hippocrates (c. 460-370 BCE). He isn’t saying the Greeks modified the heads of their kids, but the Greeks knew people who did this. Specifically, the Macrocephali of which he says:

There is no other race of men which have heads in the least resembling theirs. At first, usage was the principal cause of the length of their head, but now nature cooperates with usage. They think those the most noble who have the longest heads. It is thus with regard to the usage: immediately after the child is born, and while its head is still tender, they fashion it with their hands, and constrain it to assume a lengthened shape by applying bandages and other suitable contrivances whereby the spherical form of the head is destroyed, and it is made to increase in length. Thus, at first, usage operated, so that this constitution was the result of force: but, in the course of time, it was formed naturally; so that usage had nothing to do with it … If, then, children with bald heads are born to parents with bald heads; and children with blue eves to parents who have blue eyes; and if the children of parents having distorted eyes squint also for the most part; and if the same may be said of other forms of the body, what is to prevent it from happening that a child with a long head should be produced by a parent having a long head?

I’m not convinced that Hippocrates understands heredity here. In fact, I would be tempted to classify this alongside reports of far off people whose heads are in the middle of their chests. That is to say, as a myth, except that we know there really were people near Hippocrates doing this. Greece itself has turned up a few skulls with artificial shapes, and it was definitely going on in Turkey, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and the Levant. We know because we have the skulls (Lorentz, 90). I’m pretty sure we don’t know which of all those places was home of the Macrocephali.

You may have noticed that Hippocrates says nothing about gender here, and unlike most of my topics, this one doesn’t seem to be particularly gendered. Cultures who did it, generally did it to both boys and girls, but by and large it was women who were doing the modifying. It was a mom’s job (Tiesler, Bioarchaeology, 4,25).

In Mesoamerica it was mom’s job for thousands of years (Tiesler, Bioarchaeology 23), but it wasn’t all the same. One researcher said the varieties of head shapes “are so numerous that they are bewildering” (quoted in Tiesler “Olmec”). Slanted heads were popular along the Mayan lowlands, More erect heads were preferred in the highlands (Tiester, “Olmec”, 291). The older Olmec heads are pear-shaped (same, 307). Cranial modification was still going on when the Spanish showed up to document it. Various chroniclers said it had something to do with noble status and also for distinguishing between various ethnic groups (Duncan, 200).

But another possibility is religion. In the Mayan worldview, the soul or essence resided in the head. It could also be lost through the head. Hair is a protection, but infants often haven’t got much of that. The bindings and boards that shaped the head may have served a similar function (Duncan, 206).

One further thought about cranial modification. Many beauty routines are downright damaging to the body. I am sure you can think of a few. Maybe even a few that you participate in. Cranial modification sounds like it would be terrible, right? But actually, we don’t know that. Head binding does not seem to cause pain or damage the bones (Lorentz, 75). It simply redirects the direction they grow. Several studies have shown the cranial capacity is the same, no matter the shape. Another says it could cause cognitive and vision problems, while admitting this is theoretical (Peters). There just aren’t enough people still doing this to do a more rigorous study.

Neck Elongation

The next beauty practice definitely is for women only. In the Kayan culture of Myanmar and now Thailand, women wear coils around the neck that appear to make their necks very long.

Actually, their necks stay the same. The weight of the rings actually pushes down the collar bones, making the torso and rib cage smaller than it would otherwise be. My research on how old this practice is has been very unsatisfactory. The Internet says it is a thousand years old, but without any accompanying source or data. It seems like it wouldn’t be too hard to find evidence of a practice that would be pretty obvious either archaeologically or artistically, but I came up with almost nothing.

The oldest clear reference I found is only from 1936 (Spaulding, 6). I’m not saying the practice isn’t older, but only that I have no evidence of it being older. If you have a source, send it to me!

The process starts young, though not as young as cranial modification. Longer and longer coils are added as the girl grows so that her collar bone cannot stand up. The coils may only be removed every decade or so, and it is not uncommon for the skin below to be chafed, bruised, or discolored (National Geographic).

As for why the women do it, that is as loaded a question as it is for any beauty routine. The local lore is that it started because it protected women from tiger bites, which seems pretty sketch to me. For one thing, wouldn’t men necks be equally vulnerable?

The men aren’t wearing any rings. For another thing, my sources on this are not locals and I’m not sure I trust them to accurately report what the locals say.

Another theory is that the long neck made the women unattractive to slave traders. That also seems pretty sketch to me as a reason. First because it wouldn’t work, and second because there are easier ways to be unattractive, and third because it would risk also being unattractive to the right kind of man, wouldn’t it?

The more likely reason is the same as it is for beauty routines everywhere. It is a sign of status and of belonging and of beauty in the eyes of the men who also belong.

In the modern world there is yet another reason. A woman with a long neck can bring in cold hard cash from the tourists who come to gawk at them. This is ethically troubling. Are these women modifying their bodies because they want to and should have the freedom to do so? Or are they modifying their bodies because their poverty (or their family members) demand it, and they should have the freedom to say no?

These are women who do need a way to make a living. Having been driven out of Myanmar decades ago, they are still living as refugees in Thailand. It’s not a good situation.

Piercings

I have saved for last a practice that is alive and well in modern culture. It’s piercings. Once upon a time, I was going to do a whole episode on piercings. It seemed an obvious one for this series. After all, when I was growing up, almost all girls in my area got their ears pierced and none of the boys did. It was very gendered. But surprisingly, I found the sources a little inadequate for a full episode, so it’s just a section here.

Earrings have been found from sites all the way back in Mesopotamia. Like in the city of Ur, about 2600 BCE. The Great Death Pit (yes, that’s a thing) had 68 female bodies all dolled up in jewelry, including some fat gold hoop earrings that really look remarkably 1980s to me (Metropolitan). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which owns one of these, is very careful to say that we are only assuming these are earrings because of placement. The soft tissues are all gone, so it is possible they hung from a head dress, and not the earlobe.

A thousand years later, Minoan women were wearing bigger hoops of the type I definitely wore in the 90s. And we have an artistic depiction. It really looks like it’s hanging from the earlobe.

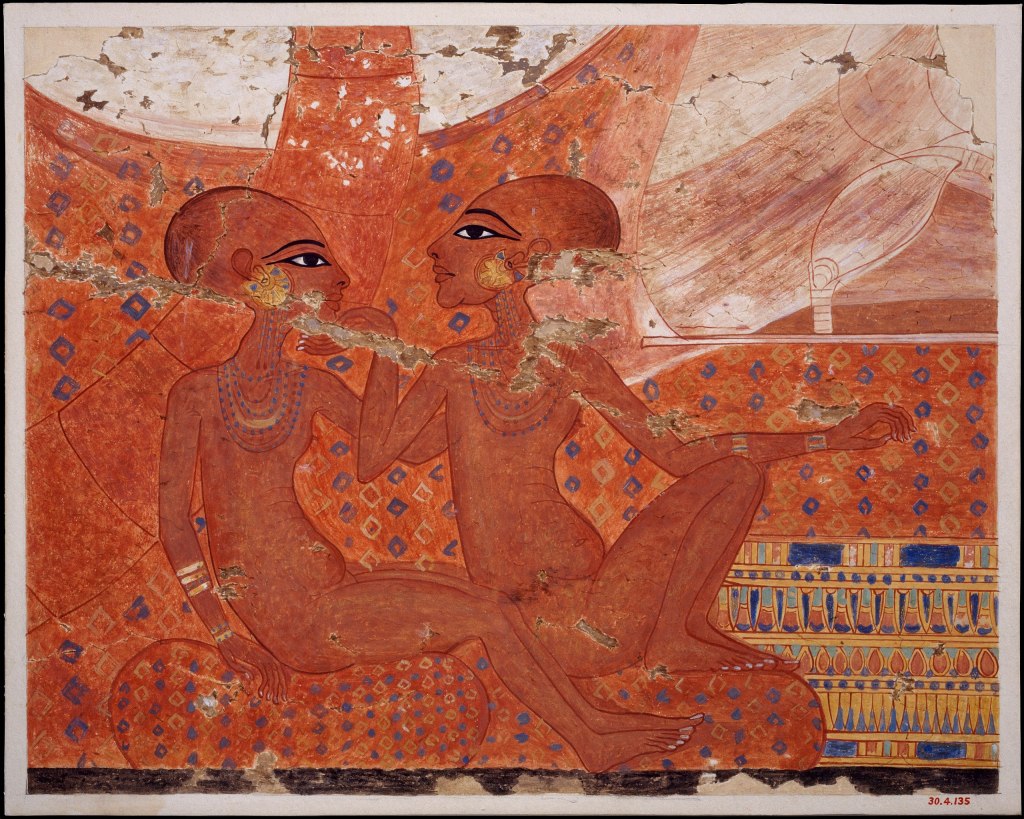

Egypt picked up the earring habit too, but there it wasn’t specifically about women. In fact, Howard Carter, the archaeologist who excavated Tutankhamun, thought it was about children, both boys and girls. He noted that Tut’s ears were pierced, but he wore no earrings. Carter was writing in the 1920s and he also noted that Egyptian kids at the time wore earrings until they were six or seven (twelve at the very latest). He thus concluded that this custom had existed in Egypt all the way along (Carter, Vol. 3, 74-75?).

To me, that seems like a really, really long time for such a custom to continue, but as long as we are speculating wildly here, I’ll add one of my own. It seems odd to put something beautiful and valuable on your kids, but not on your adults. Unless the value is not in money or in attracting a mate, but rather as a protective charm. That’s just a thought, I have no proof.

A nearby culture did put earrings on their kids, both boys and girls. In the Bible, Exodus 32:2 says that the children of Israel were to hand over the golden earrings of their wives, their sons, and their daughters, so Aaron could make a golden calf to worship. The focus of the story is just how idolatrous is that. But for today, my question is: Why not the earrings of the adult men? Is it because they didn’t wear any? Or because they got to keep theirs? The Bible doesn’t say.

Over in east Asia, they knew all about earrings. Prehistoric China has plenty of hoop earrings, sometimes in jade, and later on there are tassel drop earrings. The designs vary a lot and are all over China, including among ethnic minorities. Southeast Asia had a distinctive ribbed hoop earrings, as well as double headed animal earrings (Nguyen, Demandt). It is not at all clear to me whether these cultures thought this was a gendered practice or not.

It is also not clear to me how we know these were specifically earrings—as opposed to rings meant for other body parts. Other body parts were definitely getting pierced in some cultures. Lip piercings are clearly visible in statues of women in Peru in the mid-first millennia CE, and Spanish chroniclers commented on it when they showed up in the mid-second millennia CE (Cordy-Collins). That’s also a long time for a custom to survive, but still much less than the gap between King Tut and Howard Carter. Nose piercings were done by Native Americans in many places, including the Pacific Northwest in the United States. That one lasted long enough that there are photos.

(Wikimedia Commons)

Mesoamerica is particularly well known for piercings of an amazingly inventive variety. Earrings for sure. High status people also had tongue rings, lip piercings, and nose ornaments. In the highly stylized art of the few codices we have surviving, the nose jewelry is sometimes so enormous it seems like a serious impediment to minor concerns like breathing, or eating, not to mention blowing your nose. I’ve heard similar criticisms of modern piercings, especially in the 90s when they were just starting to go mainstream. But I assure you, this Aztec nose jewelry is bigger than anything I’ve seen in real life (Sousa, 43-44).

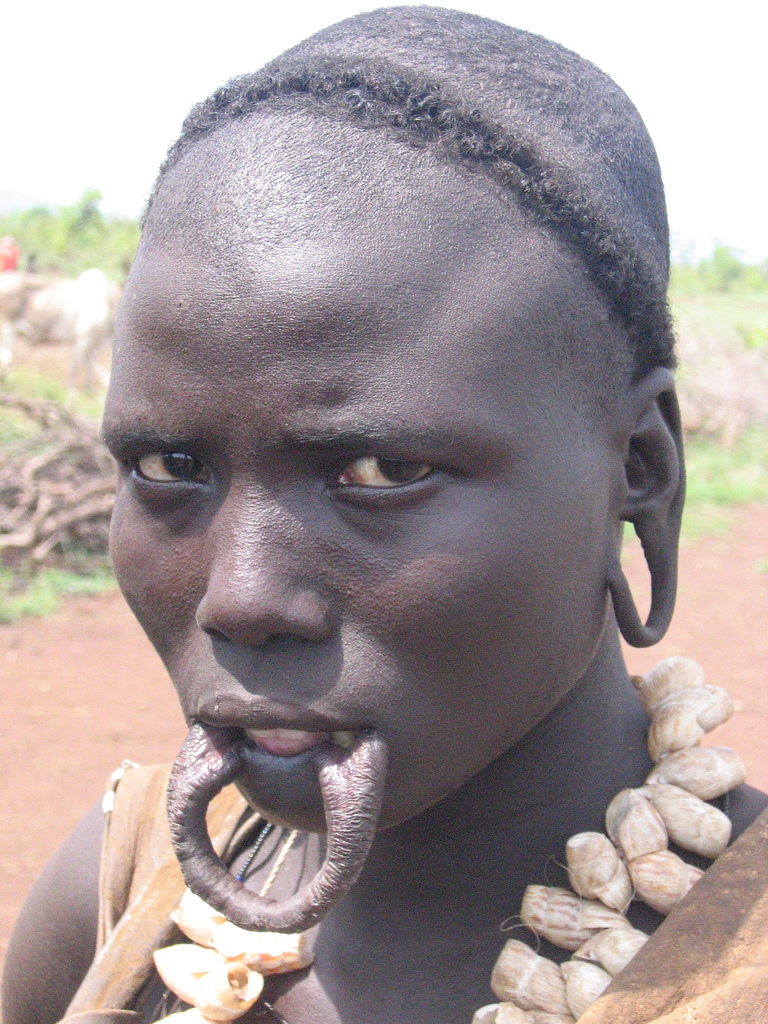

But if we’re going to talk big, then we need to head to Africa. Piercings were used all over the continent, but they are particularly well documented in the Mursi people of southern Ethiopia right up to the present day. They are the ones whose women wear large plates of pottery or wood in their lower lips.

Credits: Rod Waddington from Kergunyah, Australia and Monkeyji, both CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This is less surgical than it sounds. There is only one piercing of the lower lip, done when a girl is 15 or 16. After that, the hole is filled with progressively bigger wooden plugs, until the lips have been stretched to be big enough. That’s a subjective determination, so the size varies.

I was hoping the pierce-and-stretch method meant it wasn’t any more painful than any other one-time piercing (which is painful enough, as I remember vividly), but I was proved wrong. The girls are in pain as that lip gets stretched over months.

As with the neck rings, the reasons and the age of this tradition are obscure. It was definitely present in the 1930s (Turton), and probably well before that, I just don’t have sources. The reasons listed by Western commenters cannot be taken seriously. One their theories was that it made the Mursi women unattractive to slave traders, which you may notice was exactly what they said about the neck rings. It has all the same logical holes.

Another similarity is that lip plates are perpetuated now as a source of income. Tourists will pay good money to come see women with lip plates, even though there is more than a little ethical discomfort in doing so. The custom might no longer exist if not for the tourists (Fayers-Kerr).

As for piercings in the Western world, they took off for girls in the 1950s and grew from there. Women did wear earrings prior to that, but they were often clip-ons. Girls could do it at home with a needle and a potato, but it was pretty easy to get it done at the local mall, as I did. It was definitely gendered at this point because a boy doing the same thing was frowned on. The 80s and 90s started to change that, as well as increasing the number of body parts it was okay to pierce. We have not yet reached Aztec or Mursi inventiveness, but who knows what the next decades will bring?

Selected Sources

Allen, Margaret Prosser. Ornament in Indian architecture. London: University of Delaware Press, 1991.

Arnold, Dorothea. The Royal Women of Amarna : Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1996.

Backus, Robert L, ed., The Riverside Counselor’s Stories: Vernacular Fiction of Late Heian Japan. Stanford University Press, 1985.

Chamberlain, Basil Hall. Things Japanese, Being Notes on Various Subjects Connected with Japan, by Basil Hall Chamberlain,… 1890, archive.org/details/in.gov.ignca.17555/page/n59/mode/2up?q=teeth&view=theater. Accessed 6 Oct. 2024.

Cordy-Collins, Alana. “Labretted Ladies: Foreign Women in Northern Moche and Lambayeque Art.” Studies in the History of Art 63 (2001): 246–57. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42622324.

Demandt, Michele H. S. “Early Gold Ornaments of Southeast Asia: Production, Trade, and Consumption.” Asian Perspectives 54, no. 2 (2015): 305–30. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26357682.

Duncan, William N., and Charles Andrew Hofling. “WHY THE HEAD? CRANIAL MODIFICATION AS PROTECTION AND ENSOULMENT AMONG THE MAYA.” Ancient Mesoamerica 22, no. 1 (2011): 199–210. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26309557.

Eldridge, Lisa. Face Paint : The Story of Makeup. New York, Abrams Image, 2015.

Fayers-Kerr, Kate Nialla. “THE ‘MIRANDA’ AND THE ‘CULTURAL ARCHIVE’: From Mun (Mursi) Lip-Plates, to Body Painting and Back Again.” Paideuma: Mitteilungen Zur Kulturkunde 58 (2012): 245–59. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23644464.

Hafford, William B. “A Spectacular Discovery: Burials Simple and Splendid.” Penn Museum, 2018, http://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/a-spectacular-discovery/.

Hippocrates. “Hippocrates, de Aere Aquis et Locis, PART 14.” Www.perseus.tufts.edu, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0248%3Atext%3DAer.%3Asection%3D14. Accessed 4 Mar. 2024.

Johnson, Marguerite. Ovid on Cosmetics. Bloomsbury Publishing, 28 Jan. 2016.

Li, Nan. “The General Evolution of the Function of Ancient Ear Ornaments.” Francis Academic Press, vol. 2, no. 6, pp. 94–99, francis-press.com/uploads/papers/iFYcdJWdIiMGtZGxQXfDnMZlyAwFRsJ5T4tzkdRM.pdf, https://doi.org/10.25236/FER.020617. Accessed 12 Oct. 2024.

“Life in Japan.” The Leisure Hour; an Illustrated Magazine for Home Reading, vol. 17, 1868, pp. 262–263, hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433081682993?urlappend=%3Bseq=288%3Bownerid=27021597765402867-300. Accessed 7 Oct. 2024.

Lorentz, Kirsi O. “The Malleable Body: Headshaping in Greece and the Surrounding Regions.” Hesperia Supplements 43 (2009): 75–98. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27759958.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Earring.” Metmuseum.org, 2020, http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/322907.

Morris, Ivan. The World of the Shining Prince : Court Life in Ancient Japan. New York, Vintage, 2013.

National Geographic. “Why Do These Women Stretch Their Necks? | National Geographic.” YouTube, 29 May 2013, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0FME1At3vmI. Accessed 23 Sept. 2019.

Nguyen Thi Hau. “Ancient Jewelry Looks Ahead and Behind.” Vietnam Heritage, Cultural Heritage Association of Vietnam, Sept. 2012, vietnamheritage.com.vn/ancient-jewelry-looks-ahead-and-behind/. Accessed 12 Oct. 2024.

Peters, Lauren R, and Marc E Hines. “Artificial Cranial Deformation: Potential Implications for Affected Brain Function.” Anthropology, vol. 01, no. 03, 2013, https://doi.org/10.4172/2332-0915.1000107. Accessed 10 Mar. 2020.

Sousa, Lisa. The Woman Who Turned into a Jaguar, and Other Narratives of Native Women in Archives of Colonial Mexico. Stanford, California, Stanford University Press. Copyright, 2017.

Spaulding, Isabel. “HISTORIC COSTUME.” The Brooklyn Museum Quarterly 23, no. 4 (1936): 162–90. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26460845.

Tiesler, Vera. The Bioarchaeology of Artificial Cranial Modifications: New Approaches to Head Shaping and Its Meanings in Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica and Beyond. Netherlands: Springer New York, 2013.

Tiesler, Vera. “‘OLMEC’ HEAD SHAPES AMONG THE PRECLASSIC PERIOD MAYA AND CULTURAL MEANINGS.” Latin American Antiquity 21, no. 3 (2010): 290–311. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25766995.

Turton, David. “Lip-Plates and ‘The People Who Take Photographs’: Uneasy Encounters between Mursi and Tourists in Southern Ethiopia.” Anthropology Today 20, no. 3 (2004): 3–8. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3695118.

Wang, Marina. “Neck Coils Worn by Karen Women in Thailand Impose Heavy Health Burden.” Canadian Science Publishing, 23 July 2019, blog.cdnsciencepub.com/neck-coils-worn-by-karen-women-in-thailand-impose-heavy-health-burden/.

[…] around the globe, women have routinely squeezed, bound, crushed, tweezed, poisoned, pricked, and stretched various portions of their anatomy, sometimes with permanent ramifications, sometimes with […]

LikeLike

The lip plates are new to me. Huh. Thanks for the exposure.

LikeLike

Thanks for listening!

LikeLike