Let me be upfront with you. I am not a breast cancer survivor or any cancer survivor. I certainly know people who are, but only in a distant way. I have not had a front row seat on the process, so I do not bring any first-hand knowledge of the emotions involved, nor do I have the medical expertise to give it a rigorous medical history.

I do bring enough research to know that anyone who has suffered in this way is not alone. This is no new disease. Most cancers are not visible to the naked eye. So a person might have cancer, but not be able to identify it from a host of other very serious conditions. Breast cancer often does get a visible tumor before the end, and so it got recorded in a way that other cancers usually did not. One of my sources goes so far as to say that for most of history, cancer meant breast cancer (Olson, ix, 9). It was the only kind of cancer that the ancients knew to be cancer.

Breast Cancer in the Ancient World

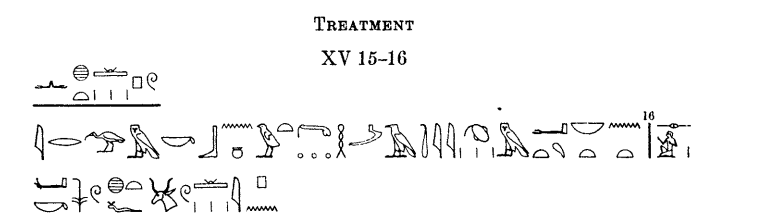

The Edwin Smith Papyrus, which dates to the 17th century BCE, is one of the oldest surviving medical treatises in the world. Case #45 within it concerns “bulging tumors on the breast”. There’s a bit about identification. And then the treatment plan, which sadly says “there is no treatment.”

But diagnosis was tricky. Breast cancer is not the only reason lumps sometimes form in the breast. More than a thousand years after some Egyptian physician said there was no treatment, a Greek physician named Democedes was more successful. The Persian Queen Atossa was the daughter of Cyrus the Great, who is best known to many as the one who conquered the Babylonian empire and allowed the Jews to go back to their homeland. The Bible likes Cyrus. (Check out Isaiah 45:1 among others). Anyway, Atossa was married to Darius the Great, who also ruled Persia after Cyrus was out of the picture. But she had a serious problem. According to the historian Herodotus, she had:

A tumour upon her breast, which afterwards burst and then was spreading further: and so long as it was not large, she concealed it and said nothing to anybody, because she was ashamed; but afterwards when she was in evil case, she sent for Demokedes and showed it to him: and he said that he would make her well, and caused her to swear that she would surely do for him in return that which he should ask of her; and he would ask, he said, none of such things as are shameful.

–Herodotus, Book III, #133

Her immediate suspicion as to what he wanted was not true. He wanted her help in escaping back to his Greek homeland. He did cure her, and she did facilitate his escape. How he cured her is the question. My secondary sources say that he lanced the tumor and cleaned it (Olson, 3-4). My translation of Herodotus says no such thing. The methods are not described at all.

If it truly was an advanced and malignant breast cancer, a lancing would not have been enough for a full cure, though perhaps Atossa didn’t know that in time to back out of her part of the bargain. Or perhaps it was not cancer at all. It might have been a relatively minor abscess or mastitis or any of a number of other things, most of them much less dangerous than breast cancer.

Breast Cancer in the Early Modern World

Two thousand years later, Anne of Austria was not so lucky. She was the queen of France. Then the regent of France for her son Louis XIII, and still the queen mother after he reached adulthood. Her struggles with breast cancer are particularly well documented because a woman in her household wrote a detailed memoir. Anne avoided doctors for a long time because she was afraid of the disease, and to be honest, they couldn’t have done much for her even if they had caught it earlier. When she finally did allow an examination, the doctors “found her breast in such a state that they were astonished … They all pronounced it a cancer, and said it was now beyond remedy” (Motteville, 311). Those are the words from the memoir, but the next page proves that not all of them found it beyond remedy. The details of the treatment are sparse, except to say that it was “hot and consequently violent,” and also that it didn’t work (Motteville, 312). Later on Anne had multiple operations (Motteville, 326, 334). The memoir says her flesh was “cut off in slices with a razor, [which was] shocking to see.” But this also didn’t work, for the doctor was cutting away the flesh that had already died, not the living cancerous mass that was killing her. She died on January 20, 1666.

It was Anne’s misfortune that she lived and died only shortly before a science really got going. Less than a century later, Giovanni Batista Morgagni published a seminal work on The Seats and Causes of Diseases, Investigated by Anatomy. That last part of the title means that he was basing his conclusions on having dissected hundreds of bodies, rather than guesswork and reliance on the long dead Classical writers. He described breast cancer. But of course, that doesn’t mean he knew how to cure it (Olson, 31; Hajdu, 1155).

Throughout the 18th century, there was growing recognition that that tumor had to go. It must be cut out. But that proved tricky for several reasons. First because they knew little of how cancer spread throughout the body, and second because they still didn’t know why some wounds got infected after the fact. Germ theory was not yet dreamed of, hand washing and sterilization were haphazard at best, and a woman who had part or all of her breast removed ran a serious risk of dying from the operation, even if the surgeon managed to get all the cancer. Oh, and incidentally, not much in the way of anesthetic either.

The most famous account of such an operation was written by Fanny Burney, a novelist much admired by Jane Austen. I have a special bonus episode on Fanny Burney, available to Patreon and Into History subscribers. It’s also available on Patreon for individual purchase as well. Here’s a quote from a letter she wrote about her 1811 mastectomy. She says:

I mounted, therefore, unbidden, the Bed stead – & M. Dubois placed me upon the Mattress, & spread a cambric handkerchief upon my face. It was transparent, however, & I saw, through it, that the Bed stead was instantly surrounded by the 7 men & my nurse. I refused to be held; but when, Bright through the cambric, I saw the glitter of polished Steel – I closed my Eyes. I would not trust to convulsive fear the sight of the terrible incision. Yet – when the dreadful steel was plunged into the breast – cutting through veins – arteries – flesh – nerves – I needed no injunctions not to restrain my cries. I began a scream that lasted unintermittingly during the whole time of the incision – & I almost marvel that it rings not in my Ears still? so excruciating was the agony. When the wound was made, & the instrument was withdrawn, the pain seemed undiminished, for the air that suddenly rushed into those delicate parts felt like a mass of minute but sharp & forked poniards, that were tearing the edges of the wound. I concluded the operation was over – Oh no! presently the terrible cutting was renewed – & worse than ever, to separate the bottom, the foundation of this dreadful gland from the parts to which it adhered – Again all description would be baffled – yet again all was not over, – Dr. Larry rested but his own hand, & – Oh heaven! – I then felt the knife (rack)ling against the breast bone – scraping it!

Agony aside, it worked. Fanny Burney lived for many more years. Which might mean that the tumor was benign all along. If the cancer had already spread, the operation probably wouldn’t have been enough. It also means she survived an operation by surgeons who didn’t yet know about germ theory.

Though I have thus far mentioned Western women who are well represented in my sources, of course breast cancer did not confine itself to one part of the world. One of the high-profile non-western women who had it was Queen Kapi’olani, chiefess of Hawaii. In 1841, she went under the knife herself, and though she was not a lively writer who left us a detailed description of it, it was without anesthesia, just as Fanny Burney’s was. She died a few weeks later. Not of cancer. But of infection (Olson, 48)

It wasn’t until 1847 that Ignac Semmelweis suggested doctors could save lives simply by washing their hands as they moved from one patient to the next (Olson, 48). It wasn’t until 1869 that John Lister published the suggestion that Pasteur’s work in microbiology explained what the mechanism was.

Breast Cancer in the 20th Century

None of that cured cancer, of course, but it did lower the probability that the woman would die in the aftermath of the operation itself. That and the development of anesthesia allowed for ever more aggressive operations targeting larger and larger areas of the woman’s body, looking for anywhere the cancer might have spread. Radical mastectomy was popularized around the turn of the 20th century. That is the operation in which not only the breast is removed, but also the nearby lymph nodes and chest wall. It’s more invasive than a simple mastectomy, which removed the breast only, and much more than lumpectomy, which removes only the lump.

Radical mastectomy was most popular among surgeons for decades, and it was the only possible treatment for cancer they felt very sure of. And of course, it still wasn’t perfect. Chemotherapy was not an option until midway through the 20th century, and I will not be covering that aspect in this episode on shaping the female body.

Up until this point, the historical accounts have been mostly clinical. If not, they focused on the woman’s agony and most likely death. If the woman did survive, she likely drops out of the historical record. Or at least any mention of her feelings on the subject gets dropped. If you had lost any portion of your anatomy under the surgeon’s knife … well … you were supposed to thank God you were still alive and be happy about it.

The whole subject was taboo anyway, involving both death and illness and a highly sexualized body part. It was okay to talk about it in clinical settings, but in clinical settings it was clinicians who did the talking and almost all of them were male. In 1963, for example, a surgeon gave a presentation on mastectomy to assembled physicians and students. He had with him a woman who had had a radical mastectomy 15 years earlier. In the Q&A section, someone asked how did the woman feel about losing her breast? The surgeon apparently thought he was the best qualified person there to answer that question, and he did. The patient, he assured everyone, had had 15 cancer-free years that she otherwise would not have enjoyed. He went so far as to lift up her remaining breast and to say that the missing one had “no cosmetic value” anyway. The woman, herself, said nothing. Presumably, no one expected her to have an opinion on the subject, much less a voice (Lerner, 3).

By the 1970s women were sick and tired of this, and a series of high-profile women changed the narrative. These included Babette Rosmond, author and editor at Better Living and Seventeen magazines. Under a pseudonym, she went public both about her breast cancer diagnosis, and her insistence on getting a second opinion after the first doctor said she needed a radical mastectomy or she’d be dead in three weeks. She sought out another doctor who said a lumpectomy would be enough, and he was right. The New York Times reported that she proudly declared “I think what I did was the highest level of women’s liberation … I said ‘No’ to a group of doctors who told me, ‘You must sign this paper, you don’t have to know what it’s all about.’ Women are finally beginning to question things like this” (Klemesrud).

Also in the seventies, Shirley Temple Black was no longer the most recognized child star in Hollywood, but her name was not forgotten. People took note when she went public with her breast cancer experience, her simple mastectomy, and her plea to all women to get examinations early. But she, too, had a complaint against the current medical practice, and she said so. It was typical form for a surgeon to put a woman under general anesthesia for a biopsy. Then if he (maybe she, but probably he) found that the lump was malignant, he would go ahead and do the mastectomy while the patient was still asleep. The result was that women went under not knowing if they even had cancer and woke up with a missing body part. The idea was that it spared the patient from the trauma of two separate procedures, but Shirley Temple Black was having none of that. She said:

“I find … distasteful the prospects of waking up and finding that someone else had made a decision and taken an action in which I, lying quite inert on the operating table, had had no voice . . . The doctor can make the incision; I’ll make the decision” (Olsen, 127).

Even higher profile was First Lady Betty Ford, who was diagnosed with breast cancer just six weeks after her husband took office as President of the United States. She had a radical mastectomy and was fully public with the process. Over 50,000 letters arrived at the White House on the subject, many of them thanking her for sharing her experience (Cancer History Project).

Prosthetic Breasts

The seventies also saw another high-profile woman go public, but in rather a different way. This was Ruth Handler, inventor of Barbie, and formerly president of Mattel. I happen to have bonus podcast episode about her as well. Also available on Patreon and Into History for ongoing supporters and for individual purchase on Patreon if you are not. There is a lot about her and Barbie that is interesting, even if you’re not a fan of Barbie. But here is the part relevant today:

In 1970 Ruth had a mastectomy at a time when no one talked about that. Babette Rosmond, Shirley Temple Black, and Betty Ford were yet to go public. There were no support groups. Not even family would talk about something so indecent. Ruth grieved. But she grieved alone. She felt she had lost herself.

And in a way, she really had. Her body image with very full chest had been important to her. (There’s a reason Barbie looks the way she does.) And along with her breast, Ruth had lost her company, Mattel. It was no longer in her hands. And she was also being investigated for tax evasion. Things were seriously not good. But she had always been a woman with vision, who thrived on working hard. She just needed a new vision. And she found one.

(Originally published by the Los Angeles Times. Photographer unknown; Restored by Adam Cuerden, CC BY 4.0)

Breast surgery had been horrible, but finding a prosthetic was even worse. They were all ugly and lumpy and uncomfortable and embarrassing to buy, much less to wear. Ruth finally had one custom-made by an artistic sculptor, and it was so much better than the other options that she went back and informed the sculptor they were going into business together. She called the new company Ruthton, a contraction of her name and the sculptor’s. It was a rotten company name and she knew it. But it was her name. When she had formed Mattel with her husband and a friend, the name was a contraction of the names of the two men involved. She hadn’t known enough to get her name included. Now she did.

She called the breasts Nearly Me, and they really were that good. Part of Ruth’s goal was to break the wall of silence around mastectomy, so she was determined not to be either shy or awkward. At presentations, she invited people to stare at her breasts and figure out which one was fake. They couldn’t do it. She invited men from the audience to feel her breasts and figure out which was fake. They couldn’t do that either.

And when the point was made, and they wanted to see a sample up close, she’d pop one right out of her own shirt and pass it around the group. There was to be absolutely no shame about what the product was.

Ruth began selling in April 1976. By 1977 she had agents in high-end department stores and soon thereafter in home health stores for women who were intimidated by high-end department stores. These agents weren’t the flushing male salesclerks who had helped Ruth with the lumpy prosthetics. Ruth built a team of no-nonsense women who had had mastectomies of their own to help fit. Many of them were her original customers.

Sometimes it was Ruth herself doing the fitting. Here’s what she said about it “To take a woman who comes in, and I will work on her and very often she will be quite hostile or confused or uptight or all so unsure of herself. I take that woman, take her through a fitting, have a happy experience where at the end she’s laughing and joking and sticking her chest out and showing off what she’s wearing. Half the place is enjoying it with her, and she walks out and she gives me that look and a hug and a kiss. I never see her again [but] that’s my high” (Gerber, Barbie and Ruth, 209).

It has been almost 50 years since the women of the seventies broke the silent shame and pain of losing a breast. In the meantime, the use of radical mastectomies has gone seriously down, as they are usually not necessary. The use of mammograms for early detection has gone seriously up. So much so that starting in the 90s, some research began to show that doctors were overdiagnosing lumps and possibly giving traumatic cancer treatment to women whose lumps were never going to cause a problem (Olson, 223). There is also now the possibility of reconstructive breast surgery. None of these improvements have come without a great deal of debate, which rages on on several fronts. And of course what we would really like is a much less traumatic breast cancer treatment.

According to the National Breast Cancer Foundation, one in eight American women will get a breast cancer diagnosis at some point in their lives. A much smaller percentage of men do as well. If caught early, the survival rate is 99%. The overall survival rate, including those that are not caught early, is still 91%. That leaves breast cancer as the second leading cause of cancer death in women (after lung cancer), and an estimated 42,520 women will die of it in the US in 2024. The numbers are much larger in the rest of the world, of course. It’s a sobering number, but still, we’ve come along way since the day when a scribe wrote in hieroglyphics “there is no treatment”.

Selected Sources

Blakeslee, Sandra. “Shirley Temple Makes Plea Again.” The New York Times, 9 Nov. 1972, http://www.nytimes.com/1972/11/09/archives/shirley-temple-makes-plea-again-tells-women-to-avoid-delay-on.html.

Breasted, James Henry. The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, Volume 1: Hieroglyphic Transliteration, Translation, and Commentary. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1930, isac.uchicago.edu/research/publications/oip/edwin-smith-surgical-papyrus-volume-1-hieroglyphic-transliteration. Accessed 14 Oct. 2024.

Cancer History Project. “How Betty Ford’s and Nancy Reagan’s Breast Cancer Diagnoses Changed Attitudes to Cancer.” Cancer History Project, 2023, cancerhistoryproject.com/article/panel-betty-ford-nancy-reagan-breast-cancer/. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

de Motteville, Madame. “Memoirs of Madame de Motteville on Anne of Austria and Her Court. With an Introduction by C.-A. Sainte-Beuve. Tr. By Katharine P. Wormeley, Illustrated … V.3.” HathiTrust, 2022, hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015014495702. Accessed 17 Oct. 2024.

Gerber, Barbie and Ruth, Robin. Barbie and Ruth: The Story of the World’s Most Famous Doll and the Woman Who Created Her. HarperCollins e-Books, 2014.

—. Barbie Forever: Her Inspiration, History, and Legacy. Becker & Mayer! Books, 2019.

Hajdu, Steven I. “A Note from History: Landmarks in History of Cancer, Part 3.” Cancer, vol. 118, no. 4, 12 July 2011, pp. 1155–1168, https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26320.

Harman, Claire. Fanny Burney. Knopf, 2001.

Herodotus. “The History of Herodotus.” Www.gutenberg.org, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/2707/2707-h/2707-h.htm. Accessed 14 Oct. 2024.

Klemesrud, Judy. “New Voice in Debate on Breast Surgery.” New York Times, 12 Dec. 1972, p. 56, http://www.nytimes.com/1972/12/12/archives/new-voice-in-debate-on-breast-surgery.html. Accessed 17 Oct. 2024.

Lerner, Barron H. The Breast Cancer Wars. Oxford University Press, 31 May 2001.

National Breast Cancer Foundation. “Women Who Changed the Face of Breast Cancer.” National Breast Cancer Foundation, 1 Mar. 2024, http://www.nationalbreastcancer.org/blog/women-who-changed-the-face-of-breast-cancer/.

Olson, James Stuart. Bathsheba’s Breast : Women, Cancer & History. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004.

Slater, Lee. Barbie Developer: Ruth Handler. ABDO, 1 Jan. 2016.

—. Barbie: Ruth Handler. ABDO, 15 Dec. 2021.

The story of Ruth’s victories in the fitting rooms brought tears to my eyes. I may just have to pay at Patreon to hear your version of her story because I loved The Barbie Movie, despite abhoring pink.

Will you please include the link to the Patreon option to buy that episode?

LikeLike

Absolutely! The link is here. I’ll include it up top as well. Thanks!

LikeLike